Three Revolutionary Films by Ousmane Sembène: Criterion Blu-ray review

Senegalese novelist turned filmmaker Ousmane Sembène made the first feature by a Sub-Saharan African director with Black Girl in 1966. That film, along with the short Borom Sarret (1963), began his influential project of dissecting the impact of colonial occupation on the sense of identity of African people. The son of a fisherman, Sembène was educated in a madrasa and a French school, speaking French and Arabic along with his native Wolof, and worked as a fisherman and labourer before being drafted into the French army during World War Two. Returning to Senegal after the war, he became politically active, eventually making his way back to France in the late ’40s, where he worked in a factory and on the docks in Marseilles. It was there that he began writing, publishing his first novel in 1956, a social-realist story centred on the racism and xenophobia of the French towards immigrants from the country’s colonies.

Having experienced colonialism from dual perspectives – as an African under colonial rule and as an immigrant inside the oppressor’s homeland – Sembène approached his literary and cinematic project with a great deal of nuance. In his second feature, Mandabi (1968), his focus was on the complicated residual effects of colonialism after independence; the nation had internalized the structures and attitudes of the French (French remained the official language) and, among the bourgeoisie, a disdain for African traditions. In an act of defiance, Sembène shot the film in Wolof instead of French, a forceful rejection of the European perspective on contemporary life in Lagos.

While both Black Girl and Mandabi were contemporary, post-colonial stories, two of his next three features, spanning the ’70s, looked back at the colonial period, with the third once again exploring the ways in which that experience continued to shape (and deform) the culture of independence.

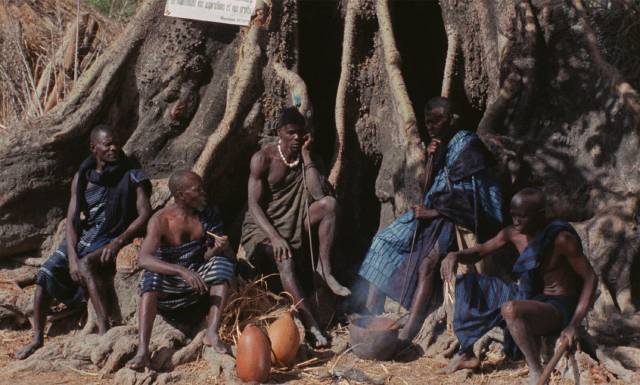

Emitaï (1971) is his most direct treatment of the colonial experience. A small village of the Diola people is disrupted when the French authorities arrive to conscript the young men to fight in Europe during the Second World War. The French officer in charge and his African soldiers brutalize the villagers until the last of the young men comes out of hiding and is marched off to the war. A year later, the authorities come to take the villagers’ rice crop to feed the army in France; some men resist and one of the elders is killed. The women hide the rice while the men hold council and consult the gods. The disregard of the French for these people and their inherent right to live their own lives in their own way is clear; the women are rounded up and forced to sit in the sun until the location of the rice is revealed. The impasse is broken when a soldier shoots a boy and the women retrieve the rice; once the rice is confiscated, the film ends shockingly abruptly with a massacre of the village men who had dared, no matter how ineffectually, to oppose their colonial masters.

Xala (1975), like Mandabi, takes a satirical view of post-colonial society, but is less naturalistic than the films which preceded it. The film begins with a group of well-off Africans seizing control of the government from Europeans, only for the Europeans to return quickly with briefcases full of money. In this way, the former colonial masters buy the allegiance of the bourgeoisie and continue to maintain control from behind the scenes. Among the Africans is El Hadj (Thierno Leye), a Muslim businessman who has stolen a shipment of rice to finance his marriage to a third, younger wife. Much of the film’s comedy comes from the weakness of El Hadj in comparison to the fierce assertiveness of his first two wives (Seune Samb and Younouss Seye), whose rivalry with one another is complicated by the introduction of their new “younger sister”.

After the elaborate, and expensive, wedding El Hadj is disconcerted to find himself impotent and humiliated the next morning by the arrival of his mother-in-law to check that the marriage has been consummated. He suspects that he has been cursed by one or both of his other wives and consults with a marabout who manages to lift the curse – until El Hadj’s cheque bounces. With his impotence closely related to his corruption, his business begins to collapse and, with the discovery of his theft of the rice, the other members of the ruling council turn against him (although they too are corrupt, just less blatant than he is).

In contrast to the bourgeoisie which tries to appropriate to itself the position and image of the former colonial rulers, the disdained population is represented by a group of the poor, including beggars with various disabilities, who occupy the street outside El Hadj’s business; these are the people ignored by the powers who have taken over from the former colonial rulers and their contempt for the ascendant African bourgeoisie, it’s implied, is the true source of El Hadj’s impotence. Things get worse when he calls in the police to arrest them; having been dumped outside the city, they make their way back as his life collapses – kicked out of the council, he’s also abandoned by his wives. When he returns home, he discovers that the beggars have occupied his house and he is finally forced to atone for his corruption by stripping and submitting to the humiliation of being spat on by these people he has considered to be beneath him.

Sembène’s next feature, Ceddo (1977), was banned for some time – strangely, not because of its radical content, but rather because the government insisted that the title – which roughly means “outsiders” – should be spelled with only one “d”. This was rooted in the tension surrounding Sembène’s use of Wolof rather than French and the control the authorities wanted to assert over that language. This seems, from the outside, a rather arcane matter, especially considering the radical content of the film.

Here, the setting is an unspecified historical past, after the arrival of Europeans and Arabs, but before full colonisation. This period spanned a couple of centuries and in the film is made even less specific by the use of deliberate anachronisms and apparent brief flashes forward to the present. Tensions are present from the start, with local King Demba War (Makhouredia Gueye) having aligned himself with the Imam (Alioune Fall) who has been converting an increasing number of people to Islam. Meanwhile, a European priest sees his Christian influence dwindling – perhaps not surprising because he’s aligned with slave traders who exchange weapons and alcohol for human beings who are chained and branded.

A group who reject both Christianity and Islam, adhering to traditional African beliefs – the Ceddo – have left the community and recently kidnapped Princess Dior Yacine (Tabata Ndiaye), the King’s daughter, to put pressure on him to throw off these outside influences. Much of the film consists of village council sessions in which the various factions argue their positions and it becomes increasingly clear that by acceding to the Imam’s demands the King has essentially given away his traditional power – until the Imam has him assassinated, kills the Christians, and forcibly converts everyone to Islam. In a lengthy ceremony, he gives every person in the community a new name, erasing their African identities and subsuming them all to his usurped power.

Having sent men to kill the Ceddo and bring the princess back to be his own bride, the Imam discovers that Africa is not so easily conquered when she returns and shoots him. Here, as in the other two films, Sembène sees women as having a strength not possessed by men; the latter are bound by structures of power which constrain and, more often than not, defeat them, while women resist and refuse to be dominated. In Emitaï, while the men sit around and discuss the situation and appeal to the gods to solve their problems, women take action – they have sown and harvested the rice and they hide it from the French. In Xala, El Hadj’s wives dominate him and his daughter Rama (Myriam Niang) sees him for the fool and hypocrite he is, and in Ceddo it’s the princess who ultimately stands up for African identity in the face of outsiders’ violence.

While Sembène’s films are colourful and full of local detail, their point of view is unlike that of outsiders who might treat this culture as a tourist attraction; his background and experiences in both his native Senegal and the French colonial homeland enable him to present his own culture and history from the inside while also making it accessible to an outside viewer. Filled with humour as well as anger and pain, by turns mysterious and transparent, his work offers a sharp and clear-eyed view of the deep harm inflicted by colonialism and the possibility of resistance to the distorted identities imposed by that brutal system of oppression and exploitation.

*

The Disks

All three films in Criterion’s three-disk set have been mastered in 4K from the original camera negatives and for the most part look excellent, with vivid colour and a lot of detail, though there are occasional signs of damage. There’s some unevenness which appears to be inherent to the material – not surprising given the constraints on production – but nothing distracting. The same is true for the soundtracks, which reflect less than ideal shooting conditions but are nonetheless perfectly serviceable.

The Supplements

Given the position Ousmane Sembène holds in cinema history – both as a major influence on African filmmaking and as a skilful artist whose work throws valuable light on the intertwined politics and history of that continent and the European colonial powers which inflicted centuries of damage on the many cultures which occupy the land – the extras included in the set are disappointingly meagre. There’s a conversation on disk one (37:56) between Mahen Bonetti, founder of the African Film Festival, and writer Amy Sall in which they discuss his work and the importance of women in his films, and on disk three an archival documentary by Paulin Soumanou Vieyra on the making of Ceddo (1981, 27:14) – both of which provide vivid personal insights into Semebene’s personality and his conception of cinema as a radical force – but Criterion provided more substantial extras on their single-disk edition of Mandabi three years ago and seem to have missed an opportunity here to expand what is known about the filmmaker and how he accomplished such a rich body of work outside any well-established cinematic practice.

The booklet essay is by writer and film programmer Yasmina Price.

Comments