Glauber Rocha’s Black God, White Devil (1964): Criterion Blu-ray review

I should probably be embarrassed to admit that my knowledge of Brazilian cinema hasn’t advanced at all since I wrote about Nelson Pereira dos Santos’ How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (1971) six years ago – a little Carlos Diegues, a touch of Walter Salles, a bruising dose of Hector Babenco, and the transgressive horrors of José Mojica Marins … but nothing at all from one of the key figures of Cinema Novo, Glauber Rocha, until Criterion’s new release of his second feature, Black God, White Devil (1964), made when he was only twenty-four.

In much of the world, as the ’50s drew to a close, younger filmmakers pushed against entrenched national industries, seeking to overturn moribund conventions and introduce a potent mixture of politics and aesthetics into movies which aimed to provoke complacent audiences as much as authorities invested in the status quo which had emerged during recovery from the Second World War. While the French nouvelle vague, a product of intellectual critics taking up production to create new forms of cinematic expression, seemed to lead the way, the roots went back to Italian Neorealism and even further to the experiments of Soviet silent film and committed Leftist productions of the ’30s. These strains gave rise to a conceptual explosion which reflected and contributed to the social upheavals which defined much of the ’60s. Nothing was sacred – class, politics, economics, religion, sexuality – everything was open to reexamination.

While the French filmmakers aimed at form itself and the English “kitchen sink” directors took on issues of class, Brazilian cinema novo seems harsher, more violent, and in some ways more urgent. These films were emerging from a less settled society, fraught with greater inequalities and deeper injustices. This is certainly true of Rocha’s film which was rooted in actual events and presented versions of real historical figures transformed into archetypes. Visceral in its details, Black God, White Devil is abstract in its treatment of narrative and character, edging into surrealism and at times approaching magic realism. While Rocha depicts emotionally wrenching events, his style – drawing on though not adhering slavishly to Neorealism and the nouvelle vague – holds the audience at a distance. This method of provoking engagement while demanding a cooler intellectual appraisal of the material may not always be successful, but the film nonetheless conveys the filmmaker’s deeply held anger towards historical (and contemporary) injustices.

If there’s a discernible model (or analogue) for this approach, it may well be Pier Paolo Pasolini’s mixture of poetry and politics which quickly led from the neorealist Accattone (1961) and Mamma Roma (1962) to a documentary-style Marxist interpretation of the Bible in The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964). While Pasolini viewed religion through a political lens, Rocha explored the limits of religion as a revolutionary force, with a commitment to transcendent belief producing a form of madness which leads to a violent dead end.

But before the film reaches that implosion (around the halfway point), it begins in the concrete details of poverty and oppression. The opening section most obviously draws on Neorealist influences, but also establishes the film’s polemical intentions with imagery embodying visual metaphors. A refrain running through dialogue and narration declares that “The land will become sea, and the sea will become land”, a prophetic assertion that an unequally structured society will eventually be overturned. Under the opening titles, the camera tracks across a barren, rocky landscape – there’s no sense of scale, so we might be either close to the ground or flying high above it – while in the final moments, it tracks across a dry shore and out over waves rolling in from the sea, suggesting a historical progression which is inevitable despite the individual suffering and setbacks experienced by the characters.

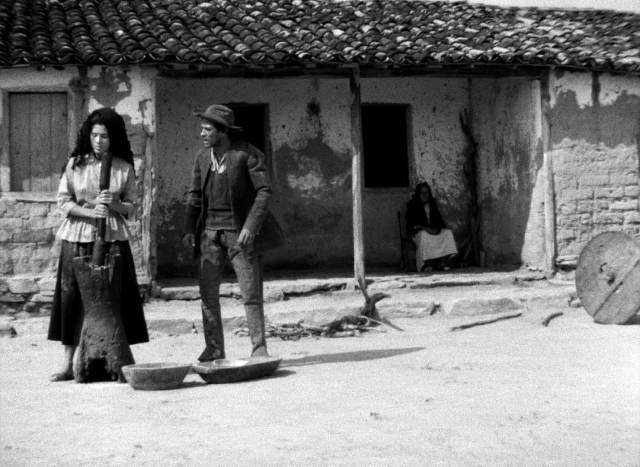

That opening landscape cuts jarringly to a pair of close-ups of a dead cow – its bared teeth and an eye crawling with flies – which in turn give way to a close-up of Manoel (Geraldo Del Rey), his expression inscrutable. The cut establishes a connection between the dead cow and the peasant, an ominous sense of shared identity. Mounting his horse and riding away, Manoel comes across a group of people following a figure carrying a cross, the mystic Sebastião (Lidio Silva); curious, he circles the procession before riding home, where his silent wife Rosa (Yoná Magalhães) grinds manioc root into flour. She continues stoically, ignoring what he tells her about going to town to conclude business with his employer.

That man, for whom Manoel tends a small herd of cows, contemptuously tells the peasant that the four dead cows are Manoel’s share of the herd and he owes his impoverished employee nothing. They argue and the wealthy man strikes the poor man with a whip; the poor man responds by drawing his machete and striking his employer. Racing home, he’s pursued by two men and in the ensuing fight, one of them kills Manoel’s elderly mother before he kills them both. With nothing left to lose, Manoel and Rosa head for a mountaintop church where Sebastião has gathered a cult of worshippers. Manoel becomes a devoted follower as the cult head out to cleanse the land of sinners. This section, whether intended or not, contains visual echoes of Pasolini’s St. Matthew, although thematically it reverses that film’s transformation of religion into political action; here, political imperatives are addressed via religious mysticism and the authorities respond to the threat to their power by sending troops to massacre the cult, an incident based on events which had occurred in the 19th Century.

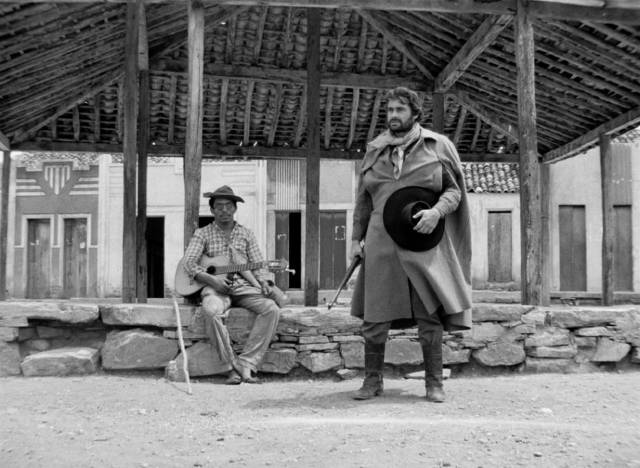

From here, Manoel moves on to yet another alternative response to the bleak conditions of his life, once again based on actual events, although again they take on a mythical, metaphoric quality. Well into the 20th Century, in this remote region of Brazil, bandits called cangaceiros preyed on the scattered inhabitants, acquiring a kind of Robin Hood reputation. Manoel becomes an acolyte of Corisco (Othon Bastos), who himself succumbs to a kind of madness which echoes Sebastião’s, although rooted now in a material rather than mystical view of the world.

Set against Manoel, Sebastião and Corisco is a representative of the government, Antônio das Mortes (Mauricio de Valle). Again based on a real-life figure, Antônio is a mercenary contracted to eradicate all threats to the established order – having led the massacre of Sebastião’s cult, he pursues Corisco and his gang, eventually tracking them to the coast where he kills the cangaceiro as Manoel and Rosa run across the barren ground until they reach the shore, land and sea coming together with an as-yet unfulfilled promise of social and political transformation.

As the film moves through its various stages, observing the harsh conditions of its characters’ lives and exploring a number of responses to those conditions, a commentary is provided by ballads on the soundtrack which further transform events into folklore and legend. This paradoxically seems to foreclose on the possibility of meaningful change, giving what is shown an air of inevitability … no real path to social and political transformation is presented so Manoel and Rosa can do little except to keep running, trying to remain ahead of Antônio das Mortes, the literal avatar of Death who serves to maintain the oppressive status quo.

*

The disk

The Criterion Blu-ray has been mastered from a 2021 4K restoration from the original camera and sound negatives. Rich in detail, with subtle contrast, the image conveys the stark landscapes and stoic faces with dramatic power. The post-synced dialogue and dubbed effects, along with music and sung commentary, add to the folktale ambience. Given the whiteness of the landscape, the subtitles are occasionally a little difficult to read and would have benefited from the addition of a slight tint to the font.

The supplements

Criterion’s edition comes in a two-disk set with hours of extras, beginning on the first disk with a commentary by restoration supervisor Lino Meireles, who ranges from the place of the film and Rocha in Brazilian cinema (he considers it the true beginning of Cinema Novo, previous films having borrowed their style and aesthetics from foreign models) to the meaning of individual visual details and the process of restoration. There’s an interview with film scholar Richard Peña (22:25), who talks about Rocha and the politics of Cinema Novo. Also on the first disk is Memoria do cangaço (29:00), a documentary from 1964 about the outlaws who arose in Brazil’s backcountry in response to harsh economic conditions. It’s startling to discover how recently they operated as former cangaceiros are interviewed along with those who hunted them, racking up so many kills that they had lost count.

The second disk contains two feature-length documentaries. I confess I found both stylistically irritating, but they contain a lot of contextual information which illuminates the importance of Black God, White Devil in both Brazilian and world cinema. Silvio Tendler’s Glauber the Movie, Labyrinth of Brazil (2003, 1:37:54) revolves around Rocha’s death and funeral, with friends, colleagues and collaborators speaking about his personality and the meaning of his work, along with archival material of Rocha presenting his ideas and working on various projects.

Cinema Novo (2016, 1:32:27) by Eryk Rocha, the filmmaker’s son, presents a broader picture of the movement in which his father played a key role, featuring new and archival interviews with other important participants.

These two documentaries and the commentary have been ported over from the UK release by a new company called Mawu Films.

There’s also a restoration trailer and a booklet essay by film scholar Fabio Andrade.

The Blu-ray release of Black God, White Devil makes full use of the format not only to make available an important film but also to provide the historical and critical context which illuminates just why it’s important. This is one of Criterion’s most substantial releases so far this year.

Comments