Resurrecting a disparaged monster: Reptilicus (1961) in 4K

I have fairly eclectic tastes in movies, though in recent years I’ve found myself increasingly drawn to the lower end of the cinematic spectrum as much as my conscience prods me to devote my limited time to more artful films. But even as I wade in this particular end of the pool, I like to think that I look for things to appreciate even in the most ragged and resource-challenged movies – having been a filmmaker myself, I know how hard it is to mount a project and follow it through to completion, so to some degree I want to honour the effort even if the end results fall short. This tendency has been facilitated by the proliferation of niche labels devoted to genre movies, companies which have been unearthing and restoring movies which were originally made, and consumed, as disposable commercial products which may or may not have reflected sincere creative impulses on the part of their makers.

Where I once used to browse for hours in stores hoping for something unexpected to reveal itself to me, now I wait for the monthly announcements of new releases from companies scattered around the world. These include Arrow, Indicator and 88 Films in the U.K., Imprint and Umbrella in Australia, and Vinegar Syndrome, Severin, Shout! Factory, Synapse, the recently discovered Terror Vision and others in the States. Because of bundling – a discount if you order everything being released in a particular month – I end up with a lot of disks I might not have bought in a more rational moment, and sometimes these prove to be more interesting and entertaining than my conscious choices. And sometimes I find myself with some real rubbish that I trade in for other movies at my favourite local store. My collection continues to expand more quickly than my ability to watch what comes in, which exerts its own uncomfortable pressure to be more judicious, but on good days I come to terms with my addiction and manage to enjoy those movies I do watch without being stressed by the weight of those I haven’t got the time for.

That said, I am ambivalent about my Vinegar Syndrome subscription. Each month, I look at what will be coming to me automatically, hoping to be excited, but usually having mixed feelings. I’m baffled by some of their programming decisions even though I recognize where they’re coming from. That is, as with some of Severin’s releases which seem inexplicable (Barry Mahon’s The Dead One [1961], Brett Piper and Samuel M. Sherman’s Raiders of the Living Dead [1986]), responses on social media are often enthusiastic, so these companies are obviously responding to niche audiences willing to pay for these movies – and I’m in no position to criticize since I also love certain movies that other people look down on, if not outright despise. And in the end, I have to appreciate the range of what’s on offer. For every Flesheater (S. William Hinzman, 1988) or Rabid Grannies (Emmanuel Kervyn, 1988) there might be a Killer Condom (Martin Walz, 1996) or Poison for the Fairies (Carlos Enrique Taboada, 1986), and sometimes preconceptions may be overturned in gratifying ways.

Which brings me to Reptilicus (1961). I’d never seen this movie – although I have a soft spot for the revived-dinosaur-on-a-rampage genre – because it’s reputed to be the worst and most risible example. Bill Warren begins his entry on the movie in Keep Watching the Skies by asserting unequivocally “This is an atrocity, perhaps the worst giant-monster-on-the-loose film ever made…” So why on earth was Vinegar Syndrome announcing a 4K restoration in a three-disk, dual-format edition which presents two different versions along with a commentary and three interview featurettes totalling seventy-two minutes of opinions from a variety of filmmakers and critics including Kim Newman and Stephen R. Bissette among others. I feared the same experience I’d had when slogging through Flesheater.

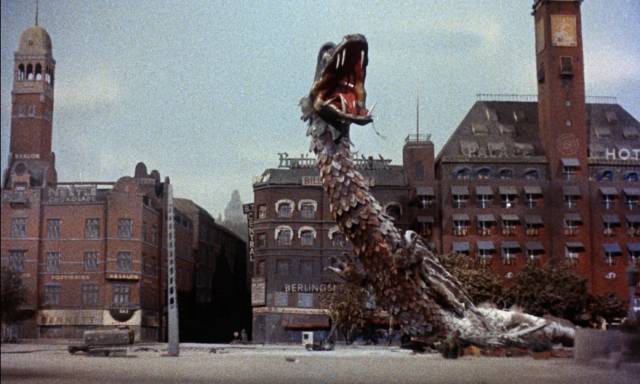

Perhaps very low expectations have something to do with it, though no doubt my own idiosyncratic tastes played a big part, but for all its many flaws I not only enjoyed Reptilicus in both its versions – I ended up admiring certain things and feeling a genuine affection for the movie. Yes, the effects are often pretty bad and some of the performances are rather painful, but there are some impressively mounted sequences and the amateurishness of the monster itself is quite endearing. Rather than the stop-motion of Ray Harryhausen’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) or the man-in-a-suit monsters of Gojira (1954) and Gorgo (1961), the makers of Reptilicus settled on a puppet, not unlike The Giant Claw (1957). As I’ve mentioned here before, I have a great affection for that particular monster, which might well have served as an inspiration for the Skeksis in The Dark Crystal (1982).

But beyond the movie itself, the background of the production is interesting. Writer-producer-director Sidney W. Pink had previously collaborated with writer Ib Melchior on The Angry Red Planet (1959), which itself had famously featured a puppet monster, the bat-rat-spider which attacks an expedition to Mars, and with the Danish-born Melchior’s help managed to make connections in Denmark which led to the production of both Reptilicus and its follow-up, Journey to the Seventh Planet (1962). With joint Danish and American financing, Reptilicus was filmed simultaneously in two versions – one in Danish, directed by Poul Bang, the other in English directed by Pink himself – which used the same cast and crew, except for one actor who was replaced because the Danish performer didn’t speak English. Despite the entire cast speaking English in Pink’s version, they were all dubbed by U.S. distributor American-International Pictures because of the Danish accents.

It’s not difficult to understand the disdain for this movie expressed by people like Bill Warren or the people behind Mystery Science Theater 3000. What matters in a monster movie is obviously the monster itself – even the best movies are often quite rudimentary from any objective point of view, but if they deliver in the key area of destructive mayhem, all else can be forgiven. And even I wouldn’t argue for the quality of the effects in Reptilicus, though I do like the city street miniatures which are trashed by the monster. The creature – which is closer to a Chinese dragon than a dinosaur, with its long snaky body, small limbs and rudimentary wings – has extremely limited mobility, its mouth permanently hanging open as it sways from side to side in place. So, yes, the movie definitely falls short in delivering a convincing monster. And yet, as already mentioned, the rather amateurish effects nonetheless possess a kind of charm which, for me, echoes memories of watching Gerry and Sylvia Anderson shows like Supercar, Fireball XL-5 and Thunderbirds as a kid.

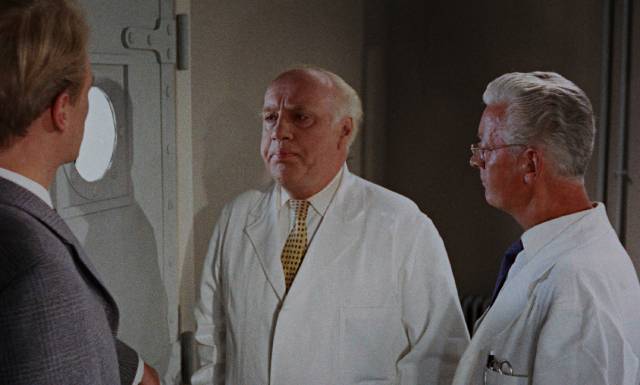

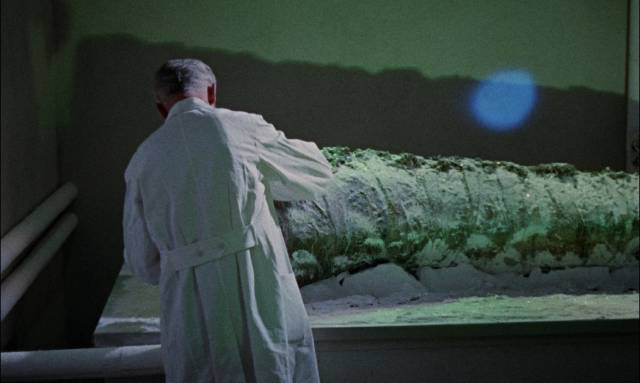

But beyond the effects, there are points of interest in the movie which, if those effects had been better, might have raised Reptilicus to the level of a Gorgo in the opinion of genre fans. Unlike most of these movies, in which a nuclear blast or an earthquake awakens a dormant prehistoric monster, the script by Melchior and Pink introduces an interesting variation. In the opening sequence a crew drilling for core samples in the tundra of Lapland bring up chunks of flesh and bone – seemingly fresh, dripping blood – and unearth a large frozen tail which is shipped to the national aquarium in Copenhagen for study. Scientists keep it frozen as they run tests, but carelessness thaws it out. Believing at first that the sample is ruined, the scientists quickly discover that it’s actually alive and regenerating. Citing the familiar point that reptiles and starfish can regrow lost body parts, the team put the tail in a nutrient bath and, before you know it, the tail has regrown a full body. During a raging thunderstorm, it escapes and, as you would expect, rampages around the countryside before returning to lay waste to Copenhagen.

All of this action is fairly typical of the genre, but the point about regeneration complicates things as the military unleashes all its fire power and the scientists warn that if they blow the creature to pieces, each fragment will grow into a new monster (this echoes the ending of Takashi Yamazaki’s Godzilla Minus One [2023]). The military, of course, can’t think of anything to do other than blowing it to pieces, so it’s up to the scientists to figure out another way – which involves using a bazooka to fire a shell full of tranquilizer into the creature’s only vulnerable spot, its mouth. It’s not actually clear what the next step will be once it’s unconscious, but at least the plan works as far as it goes…

Along the way, most of the usual stock elements come into play. The geologist who discovers the buried beast hangs around and sits in on all the high-level conferences; the scientists and military men butt heads; one of the scientists is inevitably a woman who faces sexist attitudes from the general, who eventually becomes attracted to her (these are the Kenneth Tobey and Faith Domergue roles); the lead scientist has two daughters who are attracted to the geologist; and crowds run in panic through city streets as the monster smashes miniature buildings.

As standard as all this is, there are a couple of things which actually lift Reptilicus above its American cousins: somehow, Pink obtained the cooperation of the Danish army and navy and, rather than padding the action out with stock footage, all the military activity was shot specially for the movie – convoys of trucks and tanks, soldiers letting rip with heavy duty machine guns, ships manoeuvring at sea and firing barrages of depth charges. This kind of production value was beyond the reach of most B-movies at the time and it adds an occasionally spectacular visual quality.

In addition, there are impressive crowd sequences as the population of Copenhagen flee in terror, none more so than when the crowd rushes across a drawbridge which is opening – people jump from one edge to the other until the gap is too wide, then plunge into the river below. This is all done in wide shot, without faking the action; people and bicycles go into the water for real. The stunt work is quite spectacular … but it wasn’t performed by stuntmen. A call went out to a Copenhagen athletic club, asking if people were interested in being in a movie, and hundreds showed up and performed these obviously quite dangerous stunts.

All this action footage helps to balance the weak effects to some degree, though the movie bogs down when it sets the story aside to take advantage of the Danish locations. There’s a stretch when everyone takes a break and goes sightseeing; we get a travelogue of notable local sights which ends up in a nightclub where we get a full musical number extolling the pleasures of Copenhagen nightlife. So, no, Reptilicus isn’t a well-formed movie, but many of its parts are actually quite satisfying and even those which aren’t offer some interest and amusement.

There are some notable differences between the Danish and English-language versions, the former being thirteen minutes longer than the latter. Some of that extra time includes some painful comic relief involving custodian/night watchman Petersen at the aquarium. Apparently Dirch Passer was Denmark’s most popular comedian and he mugs and improvises his way through various bits of business – this is akin to dropping Jerry Lewis into The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms or Norman Wisdom into Gorgo. Some of this business remains in the U.S. cut, but it’s not surprising that Passer’s big moment didn’t survive – for some inexplicable reason, he’s out on the lawn with a bunch of little kids singing a comic song about Reptilicus. It may only last a couple of minutes, but it feels interminable.

The U.S. cut adds some narration over the opening sequence to provide entirely unnecessary exposition which is handled with dialogue in the Danish cut; when the narration pops up again during the tour of Copenhagen, it seems even more like a travelogue. As for the performances, they seem quite consistent across both versions, though, as mentioned, the English track was re-dubbed to eliminate the Danish accents. Although positioned as the hero, Bent Mejding as geologist Svend Viltorft doesn’t have a lot to do once he’s delivered the tail to Professor Otto Martens (Asbjørn Andersen in the Edmund Gwenn role), other than to be an object of lust for the prof’s younger daughter Karen (Mimi Heinrich), who’s the most annoying character after Petersen. Carl Ottosen as Mark Grayson, the American general assigned by the U.N. to oversee research on the tail, is constantly irritable and rude, resenting having his time wasted until he has to take charge of the fight against the regenerated monster, and then irritated when the prof tells him he shouldn’t blow the beast up. For some reason, despite his sour personality, both the prof’s older daughter Lise (Ann Smyrner) and UNESCO scientist Connie Miller are attracted to him. Connie was played by dark-haired Bodil Miller in the Danish version, but replaced by blonde Marlies Behrens in the English version – at one point, during a press conference about the discovery, the English version reuses the wide shot from the Danish cut and the dark-haired Connie is sitting inexplicably beside Prof Martens, suggesting that Pink mostly just re-shot dialogue in English while using Poul Bang’s footage for the rest.

The other major difference between the two versions was altering the nature of the monster. In the Danish version it actually flies with those small bat-like wings, but American-International deemed the effect too ridiculous even for a movie aimed at kids’ matinee audiences, so the shots were dropped. In addition, to make it more menacing they animated slimy green acid spit coming out of the monster’s mouth, though apart from it having obviously been drawn over the image, it’s ineffectual because nothing was shot to show its effect on the victims – it simply fills the screen at the end of a shot, creating a clumsy wipe to the next image. Even cheesier than the spit are a couple of quick glimpses of the monster eating a farmer after it crushes a farmhouse during a family meal; a tiny photo cut-out of the farmer is simply pasted over the creature’s mouth like someone being eaten by a monster in a Terry Gilliam animation from Monty Python’s Flying Circus, though done with far less skill.

I seem to have gone on at quite some length about Reptilicus. Is it worth the effort? It’s a movie with a very bad reputation, and yet I was entertained and not in the basest so-bad-it’s-good way – there are moments of decent filmmaking along with some haphazard “comedy” and story-stopping sight-seeing, and despite the clumsiness of the effects, I nonetheless enjoyed the miniatures and the barely articulated puppet. Approaching it with low expectations and bringing to it a lifetime of idiosyncratic taste, I had fun watching both versions … so I’m obviously part of the niche audience Vinegar Syndrome was aiming at.

They certainly put in a lot of effort to satisfy that audience, with a robust 4K scan from the original negative (the 4K UHD disk contains only the U.S. cut, with each of the two versions getting a Blu-ray of its own, the Danish given an unspecified HD transfer). The commentary from Kim Newman and film historian Nicolas Barbano provides background on the production and indicates an appreciation similar to my own. Illustrator and film historian Stephen R. Bissette, becoming a familiar presence on releases like this, also expresses an appreciation for the movie and discusses its place in the genre, while Jay Jennings discusses Sidney Pink’s career after his Danish experience. Finally, film historians C. Courtney Joyner and Robert Parigi provide a retrospective account of the production and distribution of the movie.

While Vinegar Syndrome’s original announcement of the release gave me a sinking feeling, after immersing myself in the set I’m more than happy to have it in my collection alongside the company’s 4K edition of Gorgo. In fact, I took it to my friend Steve’s the other day and watched it again.

Comments