Aussie horror and Mexican luchadores and luchadoras from Indicator

Indicator have been releasing a rather confounding mix of titles recently, from another film noir set to ’80s exploitation and ’60s Mexican genre movies to comedies and dramas from both sides of the Atlantic spanning the ’30s into the ’70s. In other words, they’re all over the place.

Rene Cardona and lucha libre horror

They released three stand-alone limited editions on March 25, embodying the dizzying range of possibilities available in that most Mexican of genres, lucha libre – fantasy-horror featuring masked wrestlers combating mad scientists, monsters and injustice. All three were directed by Rene Cardona Sr., but only one includes Santo, and ironically he seems shoe-horned in and remains fairly extraneous to the action.

The Panther Women (1967)

The Panther Women (1967) draws on the tradition of Gothic horror which was already waning in Mexico by the late ’60s, as it was in other places. Shot in atmospheric black-and-white by Agustin Jimenez (whose long career began with Juan Bustillo Oro’s Dos Monjes [1934] and included, among almost two-hundred credits, several of Bunuel’s ’50s films), the story evokes Val Lewton’s RKO horror movies with its cult of witches who transform into killer cats. The coven is seeking to resurrect a warlock who was executed a couple of hundred years ago, their plan involving in time-honoured fashion the murder of the descendants of the warlock’s executioners.

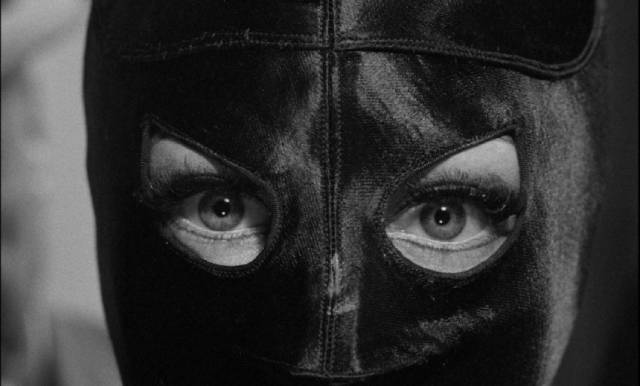

Pitted against the coven are a pair of women wrestlers (who eventually find themselves in the ring fighting against a couple of deadly panther women), who are allied with the not-Santo masked wrestler Angel, who’s also a forensic chemist (he explains his mask by asserting that “justice has no face”). Along for comic relief are a couple of ineffectual cops who are investigating the murders, which appear to be savage animal attacks. Although Angel is helpful, the film rests on the skills of the luchadoras as they track and try to stop the powerful women of the coven (even the warlock is rather ineffectual, stuck half-reconstituted in his coffin in a gloomy crypt).

The Bat Woman (1968)

Three movies later, Cardona and writer Alfredo Salazar concocted another female-centred story, though The Bat Woman (1968) is far from the previous movie’s Gothic roots. Shot again by Agustin Salazar, this one was obviously inspired by the success of the Batman TV show – filmed on sunny Acapulco locations in eye-popping colour, it mixes lucha libre and horror with a tongue-in-cheek send-up of comic book superheroes in the form of the wealthy Gloria (Maura Monti) who splits her time between being a socialite, a wrestler and a crime-fighter. In the latter role, she dons a bat mask, a short cape and a skimpy bikini.

Gloria is called in when a number of wrestlers turn up dead with their pineal glands missing. Her investigation leads to a secret lab where a mad scientist is using the glands to produce a race of fishmen. There’s no attempt here to create the kind of atmosphere seen in The Panther Women; Monti’s charm and the use of bright colours give the movie a playful tone which is reinforced by the amusingly implausible design of the fishmen.

Santo vs the Riders of Terror (1970)

Two years and fifteen movies later, Cardona made one of the odder excursions into the cinematic realm of Santo. In fact, the silver-masked wrestler seems rather extraneous to Santo vs the Riders of Terror (1970), which is set in the old West. The anachronism of a wrestling ring set up in the dusty street of a western town where cowboys are invited to challenge a luchadore rather undermines what is actually a fairly effective western. One gets the impression that a perfectly fine script was awkwardly retrofitted to justify adding Santo to the title to boost the box-office.

A half-dozen men suffering from leprosy escape from a sanatorium where they’ve been locked away as a threat to public health. The people of a nearby town are fearful of infection as the men seek food and shelter; families are terrorized as the deformed men break into their houses and soon the townspeople form a mob determined to find and kill the men, though the sheriff and the sanatorium’s doctor urge calm and argue for simply capturing the fugitives and returning them to hospital. After a while, Santo shows up to side with the sheriff against the increasingly angry and violent mob.

Eventually it becomes clear that the sick men are actually hiding out in a cave, a pathetic bunch being manipulated by a gang of outlaws who use them as cover to commit robberies. It’s up to Santo to expose the real villains and convince the lepers that the doctor has found a cure for their disease before the townsfolk show up to lynch them all.

All three movies are entertaining examples of Mexican genre cinema, which drew on trends from other countries at the time while adding distinct local flavour. As always, Indicator’s presentation of each film is impeccable, with 4K restorations of the two colour films and a 2K restoration of The Panther Women. The Santo disk includes the longer international cut with several softcore sex scenes added. Each film gets a commentary and multiple featurettes providing context and critical analysis. Each also comes in a slipcase with an 80-page book of new and archival essays and interviews.

*

Ozploitation

While modern Australian cinema was kicked off by a pair of features in 1971, both by imported directors – Nicholas Roeg’s Walkabout and Ted Kotcheff’s Wake in Fright aka Outback – it was a few years before the local industry really found its footing. By the mid-to-late-’70s, there were two fairly distinct strains: international art house hits like Gillian Armstrong’s My Brilliant Career (1979), Bruce Beresford’s The Getting of Wisdom (1977) and Fred Schepisi’s The Devil’s Playground (1976) and The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978); and exploitation, beginning with sex comedies and softcore mondo movies like John D. Lamond’s Australia After Dark (1975), which quickly evolved into thrillers and horror movies. In the latter arena, Antony I. Ginnane was a key figure as a prolific producer who gave a lot of directors their big screen breakthroughs – Richard Franklin, Simon Wincer, Rod Hardy, Michael Laughlin and others.

Another important contributor to the more commercial strain of Australian filmmaking was writer Everett De Roche, a prolific source of genre scripts, whose work provided the material which brought Ginnane together with directors Richard Franklin and Simon Wincer for initial forays by all three into horror.

Patrick (Richard Franklin, 1978)

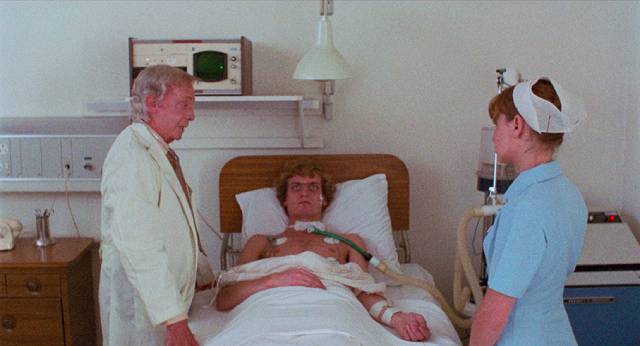

I wrote about Franklin’s Patrick (1978) a few years ago after watching it again on Severin’s Blu-ray. Indicator’s edition is a big improvement, with a 4K restoration of the longer Australian theatrical cut, the shorter, dubbed U.S. version, and the intermediate Italian cut. The movie holds up well, with its slow-building narrative and strong protagonist in Susan Penhaligon’s nurse who finds herself tending to the increasingly creepy coma patient Patrick (Robert Thompson) in the clinic of the even-creepier Dr. Roget (Robert Helpmann). The mechanism for Patrick’s psychokinetic powers remains somewhat vague (how does he project his malevolent influence to distant places where he targets people and objects with precision? – he seems like a likely influence on Brady Hartsfield in Stephen King’s Mr. Mercedes trilogy), but De Roche and Franklin manage to sustain engagement through well-drawn characters and effectively developed suspense.

Snapshot (Simon Wincer, 1979)

Simon Wincer’s Snapshot (1979), blatantly re-titled The Day After Halloween in North America, is less horror, aiming instead for a psycho-thriller/giallo vibe. The opening, with fire trucks and ambulances on a nighttime street and a charred body being brought out of a basement, sets an ominous tone before the movie flashes back for a rather soapy story in which a young beauty salon employee is persuaded by one of her clients – a pushy fashion model – to pose for her photographer friend. Young, naive, rather sheltered, Angela (Sigrid Thornton) is shy but easily manipulated and she ends up being photographed splashing in the surf topless – despite being assured that her breasts won’t be visible, she ends up in a magazine ad on full display. Her appalled, overbearing mother drives her out of the house and she takes a room above the photographer’s studio, where she’s exposed to a bohemian lifestyle.

But while she adapts to her new role, a dark shadow is cast as she’s being stalked by an increasingly menacing figure. The obvious suspect is Daryl (Vincent Gil), a guy favoured by her mother who once went out with Angela. He lurks around, spying on her from his Mister Whippy ice cream truck – an amusing detail which confounds the sense of menace by making him seem utterly clueless. Someone manages to get into her room and place a severed pig’s head in her bed and she has an unpleasant evening when a sleazy film producer invites her to his mansion for a party which turns out to be an intimate evening for just the two of them. Eventually, the narrative circles back to that street at night and the discovery of what amounts to a creepy shrine to Angela and the revelation of who has actually been menacing her – which climaxes with a grim death-by-fire.

But on the whole, the movie is pretty restrained, aiming for character rather than shock or horror. Its chief strengths are Vincent Monton’s widescreen photography, Brian May’s score, and a generally fine cast led by the young Sigrid Thornton, who gets strong support from Chantal Contouri as her pushy friend Madeline, Hugh Keays-Byrne (the Toecutter and Immortan Joe himself) as photographer Linsey, Robert Bruning as the sleazy producer, Vincent Gil as her pathetic “boyfriend” and Julia Blake as her mother (channelling a bit of Piper Laurie from Carrie). The main problem is the script – adapted by Everett De Roche and Chris De Roche from an original screenplay by Chris Fitchett – which fails to blend two distinct concepts: one, a Darling-like treatment of the exploitation and commodification of a naive young woman and the other a psycho-thriller. The latter doesn’t deliver in terms of genuine shock and violence, while the former remains familiar and superficial.

Indicator’s 4K upgrade includes both the 93-minute theatrical version and the 101-minute director’s cut, the latter compromised because the extra material had to sourced from a pan-and-scan SD tape which makes for very jarring inserts. The disk includes an hour-and-a-half of new and archival cast and crew interviews plus three commentaries, one on the theatrical cut and two on the longer version.

*

In my next post, I’ll look at Indicator’s four-disk Columbia Noir #6: The Whistler set …

Comments

I remember seeing The Day After Halloween at my local cinema. I thought it was related to the Halloween franchise and I was disappointed that I got “suckered” by the title…

So their nefarious plan worked! They got your money and that was all that mattered…