Columbia Noir #6: The Whistler: Indicator Blu-ray review

In the pre-television era, Hollywood B units churned out numerous movie series – short supporting features, frequently crime-related, typically based on familiar pulp characters or popular radio shows. There was Perry Mason, Philo Vance, Torchy Blane, and slightly higher on the production scale The Thin Man. In the mid-’40s, Universal released a half-dozen Inner Sanctum Mysteries starring Lon Chaney Jr – despite using the title, none of these were actually based on the popular radio show which ran from 1941 to 1952. In keeping with Chaney’s status as the studio’s current horror star, these leaned more towards horror than straight mystery, featuring both sci-fi and supernatural elements. Unlike the typical crime series with a continuing central character, this was an anthology series, with Chaney playing a completely different character in each stand-alone story.

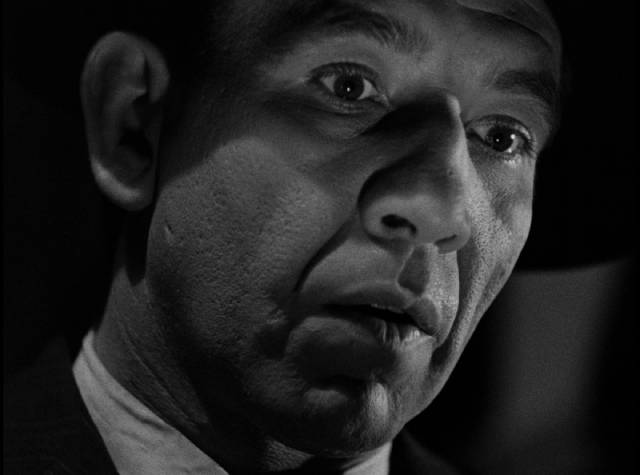

Around the same time, Columbia took a crack at another popular radio show, The Whistler, which ran from 1942 to 1955. Once again, the eight movies released over five years were not actually adapted from existing radio scripts, but were mostly original screenplays (with a couple adapted from Cornell Woolrich stories). Once again, this was an anthology series, with Richard Dix playing a different character in each of the first seven movies, replaced in the last after his death by Michael Duane. Although Columbia had dabbled in horror, particularly with their series of mad scientist movies starring Boris Karloff, for the Whistler movies they shied away from the radio show’s darker stories and aimed instead for suspense with a film noir tone; an air of doom hangs over the protagonists, frequently brought on by their own poor decisions.

The Whistler himself isn’t actually a character, but rather a mere shadow observing and commenting on the pathetic lives of mere mortals who make fatal mistakes – rather like the head-in-a-jar who introduces the Inner Sanctum movies. While providing some sense of continuity to the series, this shadow seems to take a somewhat cruel pleasure in the characters’ misfortunes.

While Dix was a decent actor (he was nominated for an Oscar in 1931), his stocky body and heavy features make him an unlikely leading man and the Whistler movies don’t shy away from making him an unsympathetic and occasionally menacing protagonist. But he’s not the real reason for reviving these minor movies; the chief interest is that four of the eight were directed by William Castle early in his career. Given a chance to direct by Columbia, he had been unhappy with the first two scripts handed to him – a Boston Blackie programmer called The Chance of a Lifetime and a western called Klondike Kate (both 1943), the latter notable because it stars both Ann Savage and Tom Neal two years before they gained immortality in Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour (1945) – so Castle jumped at the chance to direct the first Whistler script, in which he saw an opportunity to make something atmospheric and frightening.

The Whistler (William Castle, 1944)

Written by the prolific Eric Taylor, who had been churning out screenplays for Universal horrors and multiple episodes of a series based on the stories of Ellery Queen, The Whistler (1944) has a perfect hook for this kind of B-movie. Businessman Earl Conrad (Dix), inconsolable over the death of his wife (lost when a Japanese submarine torpedoed the ship on which she was returning home from Asia – the only reference in the film to the war) contacts a man who can arrange for a murder. Without identifying himself to the go-between, he gives his own name as the target. Then, after the go-between sends the details and some money to the killer by messenger, he immediately dies in a shoot-out with the police.

Knowing only that the killer will strike by Friday, Conrad receives a telegram informing him that his wife actually survived and is heading home. But he has no idea who the killer is or how to contact him to cancel the contract. Meanwhile, the killer (J. Carrol Naish) is a connoisseur of death, who enjoys toying with his targets and hopes to scare Conrad to death. It’s a neat set-up, and Castle maintains a taut pace as fate closes in on Conrad.

The Mark of the Whistler (William Castle, 1944)

Castle returned later that year for The Mark of the Whistler (1944), after two other intervening productions. This was based on a Cornell Woolrich story steeped in noir irony. Dix plays a down-and-out guy named Lee Nugent who finds a newspaper in the park and reads a story about a bank which is about to close out a bunch of unclaimed accounts. By coincidence, one of the accounts belongs to a different Lee Nugent and he sets out to find out who his namesake is (was) and, when he has enough information, he goes to the bank and submits a claim. The other Lee had disappeared as a child after his mother was killed in a fire and no one kept track of him. With the name Lee Nugent on his ID and the details he’s been able to glean, he convinces the bank he’s the rightful heir and walks out with $29,000 in cash.

Unfortunately a pushy local reporter, looking for a human interest story, manages to get his picture and, despite his objections, his good luck is printed on the front page. Which draws the attention of a man with a bitter grudge against the other Lee – Eddie Donnelly (John Calvert) is the son of a man who was ruined in business by the other Lee’s father and he figures the money should be his. The story of someone who assumes another’s identity only to discover that the other might have bigger problems has been used many times (perhaps its greatest iteration is Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger [1975]) and Castle handles it efficiently in this modest B-movie.

The Power of the Whistler (Lew Landers, 1945)

Castle was replaced on the next entry, The Power of the Whistler (1945), by the absurdly prolific Lew Landers, proving that the overall quality of such program pictures was largely due to the studio system more than the individual director. Style and tone are much the same here as in the two previous movies, though the script by Aubrey Wisberg adds a neat twist which draws on Dix’s sympathetic persona and gradually turns it on its head. Walking along a city street William Everest (Dix) distractedly steps off the curb and is knocked back by a passing car. Helped by concerned passers-by, he refuses assistance and walks away.

While sitting at a bar, he’s spotted by Jean Lang (Janis Carter) who’s out with her sister Francie (Jeff Donnell) and her boyfriend Charlie (Loren Tindall). Jean is affected by Everest’s lost look and decides to tell his fortune with a deck of cards; twice she draws the same cards which indicate imminent death. She feels compelled to warn the man and, having approached him, discovers that he has no memory of who he is. She sets out to help him, following clues in the few objects in his pockets. As they gradually discover details, her empathy takes on a more romantic shading – but we see things she doesn’t, like his penchant for killing small animals. Eventually, she and Francie are put in danger as it emerges that Bill is a homicidal psychopath who recently escaped from an asylum. This represents an interesting turn in the series, with the following three films offering Dix less sympathetic roles and, in his final appearance in the series’ seventh movie, a deeply compromised character.

Voice of the Whistler (William Castle, 1945)

Castle returned for Voice of the Whistler (1945) – by now it’s clear that the titles have little to do with the stories – in which industrialist John Sinclair (Dix), who has spent his life driven to accumulate wealth at the expense of human relationships, is told that he has at most six months to live. Searching for what has been missing from his life, he proposes a deal with his doctor’s nurse, Joan Martin (Lynn Merrick) – that she marry him and when he dies she’ll inherit everything. Fed up with waiting for her boyfriend – Fred Graham (James Cardwell), a poor young doctor with limited prospects – she accepts. In her mind, the money will help establish Fred in a research career; in Fred’s mind, she’s chosen money over love.

Sinclair and Joan retreat to a remote home on the coast (in an old lighthouse), waiting for him to die. But he soon finds himself falling in love with her and that, plus the fresh air, restores his health. Realizing that he’s not actually going to die and bored to tears by the isolation, Joan is relieved when Fred shows up one day. Welcomed in by Sinclair, who initially doesn’t understand he’s caught in a fraught emotional triangle, Fred stays and takes every opportunity to be alone with Joan having rethought his original reaction to her plan to make them both wealthy and help his career. Ironically, it’s Fred who gives Sinclair the plan for a seemingly foolproof murder … which inevitably goes wrong, ruining everything for everyone. What begins as a story of possible redemption – the cold-blooded materialist finding the true meaning of happiness in the face of death – collapses under the weight of everyone’s greed.

Mysterious Intruder (William Castle, 1946)

Greed also leads to a messy ending in Castle’s fourth and final film in the series, which strangely omits “The Whistler” from its title, suggesting that the studio wasn’t confident that the name continued to provide a box office draw. Castle directed Mysterious Intruder (1946) just before he went to work with Orson Welles as associate producer and uncredited co-writer on The Lady From Shanghai (1947) and it features what may be the most compromised character in the series.

Don Gale (Dix, of course) is a sleazy private eye who’s more concerned with exploiting desperate people than helping them solve their problems. One day an elderly man shows up in his office with an odd proposition. Antique dealer Edward Stillwell (Paul E. Burns) wants Gale to find a missing person – someone who’s been missing for decades. Elora Lund was a young girl who lived in his building with her mother, but she’s been long gone. If Gale can find her, Stillwell assures him, Elora will pay him thousands, even tens of thousands of dollars, because her mother left something very valuable with him for safekeeping and now he wants to pass it on to its rightful owner. Gale is dubious, but he takes what little cash Stillwell has as a down payment on his fee and has the old man place an ad in the personal column of the paper.

Before you know it, a woman (Helen Mowery) turns up at his shop claiming to be Elora Lund. Happy to have found her, Stillwell goes to phone Gale; while he’s gone, a man (Mike Mazurki) who’s been following the woman sneaks in and searches the cellar. When Stillwell returns, this man kills him and the woman flees. Not surprisingly, the woman is not in fact Elora, but rather Freda Hanson, sent by Gale to trick the old man out of whatever valuables he’s been holding for Elora. Things get messy when the killer himself is killed and Gale is spotted by the police running from the scene. All this makes it into the papers and the real Elora (Pamela Blake) sees the story as she recovers from an accident in a sanatorium.

It turns out that the “treasure” is a pair of wax cylinders, the only known recordings of singer Jenny Lind from the 1880s, worth around $100,000. But the scheme set in motion by Gale, rather than gaining him a hefty finders fee, leads to the destruction of the cylinders and the loss of his own life, his greed having made a deadly mess of what could have been a simple and profitable case.

The Secret of the Whistler (George Sherman, 1946)

George Sherman was a veteran of dozens of B-movie westerns when he switched to mysteries and crime movies after the war began. One notable assignment was the first adaptation of Curt Siodmak’s 1942 novel Donovan’s Brain, The Lady and the Monster (1944), itself notable for featuring Erich von Stroheim as the scientist who keeps a brain alive in a jar. After a few more war-related crime movies, and a couple of musicals, he was handed the sixth Whistler movie, The Secret of the Whistler (1946). This time out, Dix plays Ralph Harrison, an untalented artist married to Edith Marie Harrison (Mary Currier), a rich woman who has become an invalid. He throws lavish parties for hangers-on who eat and drink at his expense while speaking contemptuously behind his back.

Harrison becomes infatuated with model Kay Morrell (Leslie Brooks), and contemplates marrying her once his ailing wife dies. Unfortunately for him, she recovers with the help of an attentive doctor. Wanting to surprise him, she goes unannounced to his studio and overhears him professing his love to Kay. When Edith threatens to cut off the flow of money, he decides to bump her off and adds some poison to the heart medicine she takes every night before bed. She does indeed die, seemingly of natural causes, and he marries the gold-digger Kay. But Harrison’s compromised character guarantees there’ll be no happy ending. When Kay discovers what he has done, he kills her … only to discover too late that in her diary Edith had written down her suspicions and didn’t take her medicine, planning to have it analyzed. So she did actually die of natural causes and the artist, despite his intentions, wasn’t a murderer until he killed Kay.

The movie’s best scene comes right at the beginning as Edith places an order for an expensive headstone and tells the man to leave the date of death blank, though it shouldn’t be much more than six months. When he asks what name to carve on the stone, she tells him “Edith Marie Harrison”. Later, a reporter gets wind of this and finds it suspicious enough to keep an eye on Ralph. What follows is a low-key effort which relies more on character than suspense, aided by a decent cast and an effectively ironic final twist.

The Thirteenth Hour (William Clemens, 1947)

The final film to star Dix, The Thirteenth Hour (1947), was directed by yet another prolific B-movie craftsman. William Clemens had made series pictures featuring Perry Mason, Torchy Blane, Philo Vance and the Falcon, but his best work was probably four Nancy Drew movies starring Bonita Granville. Although his career only lasted just over a decade, he made three dozen movies, culminating in his contribution to the Whistler franchise.

The film has an interesting context – the stressful, cut-throat business of trucking which raises echoes of movies like Raoul Walsh’s They Drive By Night (1940) and Jules Dassin’s Thieves’ Highway (1949). It’s a reminder that the gritty details of working life were often sidelined by Hollywood. Dix is Steve Reynolds, owner of a small freight company who’s being pressured to sell out to rival Jerry Mason (Jim Bannon). In the opening act, random incidents and absurd coincidences pile up quickly, all compounded by Steve’s poor decision-making skills. It’s so overwrought that it plays like a parody of noir’s doom-laden narratives of good guys trapped by fate.

At a roadside diner, as the patrons celebrate the birthday of owner Eileen (Karen Morley), she and Steve announce their engagement. Steve has a drink of punch before heading back on the road. He picks up a hitchhiker, and before you know it a jerk out with his girl speeds towards the truck and runs it off the road; Steve crashes into a service station and the hitchhiker vanishes. No one saw the speeding car and, without his witness, he can’t prove what actually happened. Unfortunately the motorcycle cop who stops to investigate the accident is Don Parker (Regis Toomey), his rival for Eileen. Smelling the punch on his breath, Parker cites Steve for drunken driving and he ends up with a six month suspended sentence and the loss of his license.

But wait, there’s more trouble. Unable to find drivers and with a schedule he has to meet in order to stay in business, Steve sets out on a run despite having no license. On the way, he’s hijacked by a masked man and knocked out. Speeding, the hijacker attracts Parker’s attention and when he’s approaching the truck, the guy backs up and kills the cop, leaving Steve to take the rap. In the deepest trouble, he high-tails it to Los Angeles and hides out. After seeing Jerry Mason having a meeting at a bar and overhearing suspicious talk about a car-theft ring, Steve decides to head home and try to clear his name.

With the help of Eileen and her son Tommy (Mark Dennis) and his long-time buddy Charlie (John Kellogg), Steve investigates Mason’s shady business as the police close in on his trail. But he gets even more than he bargained for, uncovering a whole other criminal operation and becoming implicated in yet another murder… The Thirteenth Hour may be the closest to full-on noir that the series reached and while Steve is occasionally exasperating as he makes decisions which get him deeper into trouble, the script is tightly constructed and there are a number of neat narrative details which help to make it one of the best films in the series – a decent swansong for both Dix and Clemens.

The Return of the Whistler (D. Ross Lederman, 1948)

With Dix out of the picture, Columbia took one last stab at the franchise with The Return of the Whistler (1948), with D. Ross Lederman directing and Michael Duane, who had previously had a supporting role in The Secret of the Whistler as the man who introduces Kay to Ralph Harrison, in the lead. Lederman was another prolific B-movie guy whose career spanned from the mid-’20s to 1960, with the usual range of westerns, adventures, comedies and crime movies. His Whistler movie, again based on a Cornell Woolrich story, is a mystery which contains elements of woman-in-peril and Southern Gothic.

Engineer Ted Nichols (Duane) and his fiancee Alice Dupres (Lenore Aubert) arrive late one night at the home of a justice of the peace. Despite having an appointment, they find the justice isn’t there and have to find a hotel for the night. As they’re not married, and the hotel is full, he has to leave Alice alone in a small room the night clerk makes available. Next morning, Ted finds that Alice has disappeared and the room is being repainted – shades of Terence Fisher’s So Long at the Fair (1950). When Ted causes a scene, drawing the attention of the police, we get some backstory: one night in a park, he met Alice who seemed to be running from something. Offering her shelter, he learns that she had married an American soldier who died in Europe and had recently arrived in the States looking for his family. Ted falls for her, and despite only having known her for a couple of weeks, they decide to get married.

The night clerk says that some people came shortly after he left her at the hotel and she went away with them. Following clues in the story she had told him, he and the police end up at the Barkley estate where they’re told she’s insane, that she’s married to Charlie Barkley (James Cardwell), and that she’s under a doctor’s care. The police are satisfied, but Ted smells a rat. There’s also a shady private eye named Gaylord Traynor (Richard Lane) hanging around who offers Ted some help, but also seems to be working against him on the family’s behalf. It all turns out to hinge on a large inheritance – which would go to Alice if she can prove her marriage, but is coveted by her dead husband’s aunt and cousin.

The absence of Dix is felt – Duane is rather bland as the hero – though the rest of the cast does a good job. There are no sudden twists in the story and in this case it culminates in a happy ending, which makes it seem like the most lightweight of the Whistler movies and a weak ending to the series.

*

Overall, the eight-movie run of the Whistler was entertaining enough, though the ominous intros of the unseen observer-narrator suggested a bigger dose of horror than the films actually deliver. Their main claim for a place in movie history lies in helping to launch William Castle’s directing career and giving Richard Dix a minor showcase at the end of his run as a character actor.

Indicator’s four-disk Columbia Noir #6: The Whistler set is up to their usual standard, with the transfers as good as you might expect for minor studio releases like these – there are occasional flaws, but mostly they look fine. Five of the films get commentaries and there are two interviews with Kim Newman, one on the series, the other on the early career of William Castle. There’s a post-screening interview with Richard Dix’s son Robert, and an audio interview with character actor Stuart Holmes, who had a small role in Voice of the Whistler. And, as usual with these Columbia Noir sets, there are a couple of propaganda shorts – It’s Murder (1944), directed by Ed Bernds, in which careless talk on the home front leads to disaster for a military operation in the Pacific; and It’s Your America (1946), directed by John Ford, in which a soldier returning from the war contemplates what he has been fighting for.

Rather than separate essays on the films, the 120-page book includes a lengthy essay about the series by Tim Lucas and a handful of magazine articles and interviews about Dix, plus an excerpt from William Castle’s autobiography about his work on the series.

Comments