Murder, witchcraft, doppelgangers and stranded astronauts from Imprint

My latest batch of disks from Imprint includes only one movie I’d never seen, along with a couple of upgrades, one movie I saw once in a theatre long ago … and one which is, I think, a ninth dip.

Catacombs (Gordon Hessler, 1965)

Although not a great director, Gordon Hessler made some interesting horror movies in the early ’70s – Scream and Scream Again (1970), Cry of the Banshee (1971), Murders in the Rue Morgue (1972) – and spent the next couple of decades doing a lot of TV (series episodes and movies), with three Sho Kosugi martial arts movies late in his career. But he started slow in the ’60s, having worked his way up through the ranks from story reader to producer on Alfred Hitchcock’s network shows in the late-’50s and early ’60s before directing one half-hour episode in 1961. For mainstream prestige, he directed the better-than-average Ray Harryhausen vehicle The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) and wrote and directed The Girl on a Swing (1988), adapted from the supernatural romantic thriller by Richard Adams.

But halfway between that Hitchcock episode and his first horror movie, The Oblong Box (1969), he made his feature debut with Catacombs (1965), known in the U.S. as The Woman Who Wouldn’t Die. Although a minor psychological thriller, reminiscent of the Merton Park Edgar Wallace Mysteries of the early ’60s – and obviously influenced by Hessler’s association with Hitchcock (and by extension Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques [1955]) – it has a few points of interest, not least being that it was written by Daniel Mainwaring, who under the pseudonym Geoffrey Holmes had written the 1946 novel Build My Gallows High, which had been adapted the following year into one of the greatest of all films noirs, Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past; he also adapted Jack Finney’s novel for Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).

Catacombs is definitely not in that league, but it is effective in its own modest way. With only four main characters and a handful of sets, it tends to be a bit static and talky, but Hessler generates some atmosphere and the cast is fine. Gary Merrill plays Raymond Garth, a middle-aged man fed up with serving the needs of his wealthy, invalid wife Ellen (Georgina Cookson), but stuck in the marriage because he has no money of his own. Ellen is frequently racked with crippling pain, which she can partially ease with massage, though at its worst she can only find relief through self-hypnosis, putting herself into a trance.

Ellen is thrilled when her favourite niece Alice Taylor (Jane Merrow) returns after years away studying art in Paris. Alice’s arrival proves uncomfortable for Raymond because the girl who went away is now a very attractive, mature young woman. To make things more awkward, Alice seems to be attracted to him and, while Ellen is confined at home by her illness, Raymond and Alice spend time together and begin an affair.

Adding to the complications is Ellen’s put-upon secretary Dick Corbett (Neil McCallum), who can barely conceal his hatred for the demanding woman, openly floating the idea that everyone would be better off if she was dead. And so together Raymond and Dick concoct a plan for the perfect murder – facilitated implausibly by Dick finding a perfect double (also played by Cookson), with whom he’ll travel to the continent after Raymond has killed and disposed of the real Ellen. Things become messy when Ellen discovers the affair and informs Raymond that she’s going to cut him off, leaving him and Alice destitute.

As is always the case, the perfect murder runs into snags and the conspirators turn out to be hiding things from each other, which pretty much guarantees it’ll all end badly. With a nod to Les Diaboliques, Raymond’s sense of guilt is aggravated by signs that Ellen has returned from the grave to torment him. The final revelation of a secondary underlying plot isn’t terribly surprising and the ironic denouement unfortunately relies on the carelessness (not to mention stupidity) of the characters. Perhaps the best that can be said is that Catacombs is an efficient debut.

A 4K transfer from the original negative provides a pleasing image, supplemented with a commentary from Jonathan Rigby and Kevin Lyons, and interview featurettes with 83-year-old Merrow, 89-year-old score composer Carlo Martelli, and continuity person Renee Glynne and sound editor Colin Miller.

*

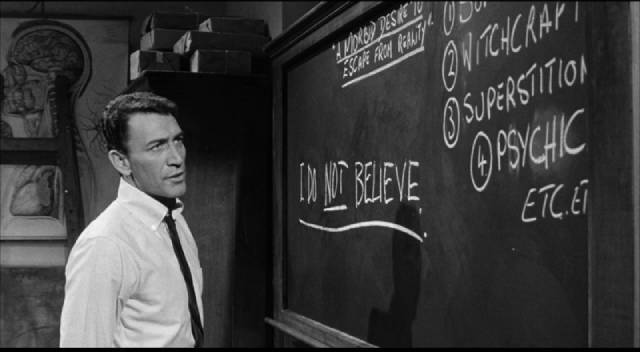

Night of the Eagle (Sidney Hayers, 1962)

Sidney Hayers’ Night of the Eagle (1962) was the second adaptation of Fritz Leiber Jr’s well-regarded 1943 novel Conjure Wife. The first was Reginald Le Borg’s Weird Woman (1944), the best of the Inner Sanctum movies starring Lon Chaney Jr. The British title was seemingly an attempt to remind potential viewers of Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon (1957), with which it shares some key thematic points. To complicate matters, when it was picked up by American-International in the States, it was retitled Burn, Witch, Burn – which was the title of the 1933 A. Merritt novel adapted by Tod Browning as The Devil-Doll in 1936. But title aside, Night of the Eagle is a very well-crafted and intelligent tale of supernatural horror with a convincingly prosaic setting at a small college somewhere in England.

Norman Taylor (Peter Wyngarde, fresh from his appearance as the ghost of Peter Quint in Jack Clayton’s The Innocents [1961]) is a strict rationalist who teaches his students to disdain all manner of superstition. Relatively new to the faculty, he is a rising star who may be chosen over older colleagues to serve as chair of the department. He’s resented by time-wasting student Fred Jennings (Bill Mitchell), who feels he deserves better marks even when he doesn’t bother to do the work, and adored by young Margaret Abbott (Judith Stott), who views him like an academic rockstar.

We quickly discover that Norman is seen as a threat to their husbands by the other faculty wives, who look down on his own wife Tansy (Janet Blair). A Friday evening of bridge with three other profs and their wives is one of the film’s best sequences, fraught with tense undertones which show through in innocuous dialogue which points towards something dark and menacing – something of which only the women present are aware. This signals the film’s complicated treatment of gender, the complacent self-assurance of men for whom the world is fully comprehensible and essentially in their control contrasted with the women’s awareness of powerful currents flowing beneath the material surface, something with which they are attuned and able to manipulate.

Leiber wrote his novel some twenty years after Margaret Murray had proposed that the medieval witch craze had not simply been an expression of patriarchy’s deepest misogyny, but had rather been the Christian establishment’s response to the survival of an ancient, female-centred paganism. In Conjure Wife and the films adapted from it, occult forces are very real and the faculty wives are all using it to prop up and forward their husbands’ careers. Tansy was introduced to witchcraft on the couple’s honeymoon in Jamaica and has secretly been practising protective magic to ward off the malevolent spells of Evelyn Sawtelle (Kathleen Byron) and, particularly, Flora Carr (Margaret Johnston), who sees that her husband Lindsay (Colin Gordon) is going to be passed over when the new department chair is named.

Unfortunately, Norman discovers one of Tansy’s charms. Although she brushes it off as a “souvenir”, he scours the house and finds dozens of objects including herbs, bone fragments, vials of grave dirt, which he insists that she burn to disavow what he sees as an unhealthy belief in primitive superstitions. She pleads with him, but finally acquiesces with a dire warning that she won’t be responsible for the consequences.

And consequences there are. Margaret Abbott accuses him of rape; a distraught Fred Jennings arrives at Norman’s office armed with a pistol, threatening to kill him for what (he believes) has been done to Margaret. Under suspicion, his entire career is suddenly at risk. The attacks become more direct and Tansy tries desperately to protect him, despite all her “tools” having been taken away. As a last resort, she tries to draw the attacks to herself, sacrificing herself to save him … leading at last to Norman’s reluctant acceptance of the forces at work, finally taking action himself to turn those forces back on the witch who is trying so hard to destroy him.

Sidney Hayers, who turned to directing after a notable decade-long career as an editor, made a number of effective B-movies, many revolving around crime, from his debut film Violent Moment in 1959, with highlights in the ’60s like Circus of Horrors (1960) and Payroll (1961) and, in the ’70s, Assault and Revenge (both 1971), before turning mostly towards television for the next three decades, working into his late seventies up until the year before his death in 2000. But in a long, prolific career, Night of the Eagle stands out as his best work … which makes it seem odd that it’s his only foray into the supernatural.

Night of the Eagle belongs to a sub-genre which, for some reason, I’m quite partial to – though I’m not entirely sure why. In these movies (from Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People [1942] and Night of the Demon [1957] to The Exorcist [1973] and beyond), rational characters are confronted with the inexplicable and after protracted resistance have to come to terms with immaterial forces which negate their firmly held worldview. Since I tend towards the same rational views as those characters – I’ve never had any religious beliefs and don’t believe in ghosts and other mystical entities – it seems odd that I take satisfaction in seeing these characters forced to face the supernatural as a reality.

Perhaps there’s an unacknowledged part of myself that would actually like to believe? Not really; storytelling obviously has connections with reality, but it’s not bound to it. Fantasy and metaphor allow us to explore ideas and emotions which can then be incorporated back into everyday life – these rational vs supernatural stories not only have the entertainment value of campfire stories which play with our fears in a safe way; they also warn us not to be too rigid and complacent in our opinions, to be open to re-interpreting what we think we know.

The Imprint Blu-ray was mastered from a 2K scan of the U.S. Burn, Witch, Burn cut and it looks excellent, with deep blacks and rich contrast. I’m not sure whether there are any differences from the U.K. version other than the title change and the addition of a three-minute intro over a black screen in which Paul Frees (sounding a bit like Orson Welles) offers a portentous warning about the reality of witchcraft which climaxes with a ritual invocation to protect the audience from whatever dark forces are about to be unleashed by the movie.

The disk includes no less than three commentary tracks – an archival one with co-writer Richard Matheson and two new ones, one with Vic Pratt and William Fowler, the other with film historian Scott Harrison; plus an interview with Peter Wyngarde, a discussion of William Alwyn’s score by David Huckvale, and a couple of video essays, one on Leiber’s novel and its adaptations, the other on director Sidney Hayers. There are also U.K. and U.S. trailers.

*

The Man Who Haunted Himself (Basil Dearden, 1970)

Basil Dearden seems an unlikely director for horror or fantasy, with the bulk of his work rooted in post-war realism, with an emphasis on social issues – from the wartime The Bells Go Down (1943) through crime in The Blue Lamp (1950) and Pool of London (1951), juvenile delinquency in Violent Playground (1958), racism in Sapphire (1959) and laws against homosexuality in Victim (1961). And yet early in his career he did dip his toes into those genres. Towards the end of the war, he made the allegorical They Came to a City (1944) and directed the framing story for Dead of Night (1945). And he returned to horror at the end, with this final feature the year before he died.

The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970) is a rather prosaic movie, more like an episode of Brian Clemens’ television series Thriller (1973-76) or the Hammer House of Horrors series (1980) than a theatrical film. But it could be argued that its lack of stylistic flair, its ordinariness, helps to ground the fantastical elements of the story. Based on a novel by Anthony Armstrong published in 1957, which in turn was based on a 1940 short story which had been adapted for television at least three times, it’s the story of a stuffy, passionless businessman who, following a car crash and a brush with death during an operation, gradually realizes that there’s a doppelganger increasingly intruding into his life, an exact double who is interfering with his business and, frankly, being more fun for friends and acquaintances. He parties, gambles, has an affair and plays a ruthless game with a company determined to take over and exploit the company he works for – in the latter case, initially appearing to be betraying his employers, although this other self actually obtains a better deal. In other words, the double is better at everything and eventually takes over his life completely, including improving his relationship with an estranged wife and two young children.

The entire film rests firmly on the shoulders of star Roger Moore, who would shortly transition out of television (The Saint [1962-69], The Persuaders! [1971-72]) when he took over the role of James Bond in Live and Let Die in 1973. Moore is perfect for the stuffy Pelham, trapped by habit and buttoned-down emotions, and he manages to maintain many of the man’s characteristics even as he loosens up as the doppelganger – it’s not so much a Jekyll-and-Hyde duality as it is an unplugging of blocked emotions; the other Pelham is no longer tightly bound by convention and caution, willing to take risks regardless of how this might affect others’ opinion of him. Moore and Dearden handle Pelham’s creeping paranoia and gradual deterioration very well and make it completely plausible that everyone around him, including his family, prefers the double.

Although definitely not up there with Dearden’s best work, The Man Who Haunted Himself is an enjoyable piece of psychological horror which gives Moore one of his best roles and surrounds him with an excellent cast of character actors, including Freddie Jones who injects a strong dose of humour as a very eccentric psychiatrist.

The disk offers a strong and colourful image – though the material might have benefited from black-and-white – and is loaded with extras including an archival commentary from Moore and uncredited co-writer Bryan Forbes and a new one from Jonathan Rigby and Kevin Lyons. There’s a fifty-minute documentary about Moore from 2015, as well as a new interview with his biographer, Gareth Owen. There’s also a half-hour of interviews with actor Freddie Jones and various crew members. Best of all, Imprint have included the 1955 episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents which was adapted from Armstrong’s short story and directed by Hitchcock himself, which offers a much simplified version of the narrative with Tom Ewell as Pelham telling his story to a doctor.

*

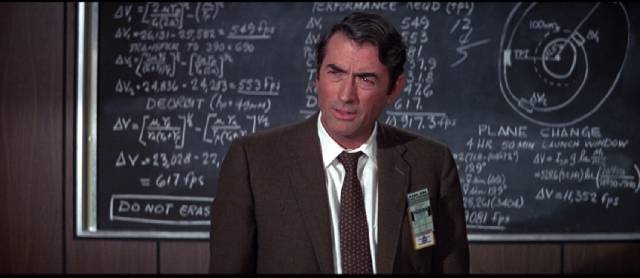

Marooned (John Sturges, 1969)

In the mid-Twentieth Century, reality began to catch up with science fiction, a genre predicated on the projection of technological developments into the future. In the ’50s, movies about space travel were fantasies which drew on current theories and research. Then, from the end of the decade and throughout the ’60s, reality displaced fantasy as first satellites were sent into orbit and then animals and finally human beings. Space flight was no longer pure fantasy; of course, it was (and still is) possible to project into the future and add fantastical elements to a technology which had surprisingly quickly become rather prosaic. There was Robinson Crusoe stranded on Mars, a planet which no human has yet visited (though we’ve sent many exploratory probes in the ensuing six decades); there was the mysterious alien influence on human evolution in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

But what to make of John Sturges’ Marooned (1969)? Martin Caidin wrote the source novel in 1964, as NASA was transitioning from the Mercury program to Gemini. In the book, a lone astronaut in a Mercury capsule is stranded in orbit due to a technical malfunction and the Space Agency mounts a rescue mission with the as-yet untried two-person Gemini capsule. While the book was optioned and in development for several years (initially with none other than Frank Capra set to produce and direct in 1965), by the time the movie eventually went into production both the Mercury and Gemini programs were past history and Apollo was underway. In fact, the film eventually premiered in November 1969, almost a year after Apollo 8 had flown to the moon and made ten orbits, four months after Apollo 11 put the first humans on the moon’s surface, and four days before Apollo 12 was launched for a return trip. (Hard to believe now that the first two landings took place in the span of just four months.)

And given the plot of the movie, it seems strangely prescient that it was released four months before the flight of Apollo 13, giving audiences a glimpse of the kind of procedures which were used to bring that mission safely back to Earth after near-catastrophic failures. So, in this context, does Marooned count as science fiction? Much of it reflects what was actually going on at the time in terms of the technology and institutional procedures arising from those developments. The only projection, at the start of the movie, is the manned orbiting lab in which the three astronauts have been living and working for months … essentially Skylab, which had just begun development at the time and was finally launched in May 1973. There’s also the climactic sequence in which a Russian Soyuz craft is diverted to aid in NASA’s rescue effort, something which wouldn’t actually happen until 1975 with a joint Apollo-Soyuz mission.

This kind of confluence of real-world developments and storytelling, which also shows up in Robert Wise’s The Andromeda Strain (1971) – adapted from the novel by Michael Crichton, whose work echoed Caidin’s novels in their use of cutting-edge technology – blurs the distinction between reality and science fiction. So, while much of Marooned takes place in orbit, the movie plays very much like Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 (1995), although it’s inevitably less technically polished – the model work and effects are not always convincing, more like a George Pal production from the ’50s than the meticulously detailed imagery of 2001.

The question, after my long-winded diversion about these issues of genre, is whether Marooned works as drama. John Sturges had been a reliable if rather uninspired director since the mid-’40s, making his finest film, Bad Day at Black Rock, in 1955. He was often associated with westerns – including two of the best movies about the famous clash between Wyatt Earp and the Clantons in Tombstone, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957) and Hour of the Gun (1967). In the ’60s, his work was often fairly impersonal as he made a number of big-budget productions like The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Great Escape (1963), the overblown (comedy was definitely not his forte) The Hallelujah Trail (1965), and Ice Station Zebra (1968). In the ’70s, he had a run of troubled productions, leaving Le Mans (1971) after conflicts with star Steve McQueen, butting heads with Clint Eastwood on Joe Kidd (1972), more conflicts in Spain on The Valdez Horses (1973) starring Charles Bronson. He capped his career with the John Wayne dud McQ (1974) – apparently Wayne’s attempt to recover from turning down Dirty Harry (1971) – and the solidly old-fashioned The Eagle Has Landed (1976).

Marooned, like The Satan Bug (1965), plods through its objectively dramatic story with little sense of excitement, with Sturges going through the motions like a director-for-hire rather than someone who is personally invested in the material. I saw it back in 1970 (having read Caidin’s revised novel which awkwardly updated the original to reflect the changes made in the adaptation by Mayo Simon, who went on to script Saul Bass’ Phase IV [1974] and Richard T. Heffron’s Futureworld [1976]) and found it pretty dull. Strangely, seeing it again five decades later, I enjoyed it more. The difference is context. Back then, I was looking for science fiction; now, in a post-Apollo 13 world, I was engaged by the prosaic attention to technical process (as I am in The Andromeda Strain).

The characters may belong more to soap opera than high drama – script and director have no idea what to do with the three astronauts’ wives, played by Lee Grant, Mariette Hartley and Nancy Kovack, and so the actresses can only sit there and fret, while the astronauts trapped in their capsule range from stoic (Richard Crenna) to poetic (James Franciscus) to psychological meltdown (Gene Hackman). Meanwhile, on the ground, mission supervisor Gregory Peck has to make the tough decisions about when to cut the losses and let his men die in orbit … until astronaut Ted Dougherty (David Janssen) demands the impossible and insists that, dammit, they have to mount a rescue mission, using an untried experimental reusable orbiting vehicle – a smaller prototype of the eventual shuttle. While reason says that setting this up would take weeks, he insists it can be done in a couple of days by scrapping most of the safety procedures.

While Dougherty supervises preparations and takes a crash course in flying the new vehicle via a training simulator, Peck oversees a ground crew working hard with a duplicate of the stranded capsule trying to figure out the technical problem with the malfunctioning retro rockets and just how the dwindling oxygen supply can be stretched until the rescue vehicle can reach the capsule. And wouldn’t you know it, there’s a very narrow launch window and a hurricane is moving in towards Cape Canaveral. Everything is ready to go, until the winds become too strong and the launch is cancelled in the final seconds … but wait! The eye of the hurricane will pass directly over the launch site and the calm might just last long enough to get off the ground … only there won’t be enough oxygen to sustain three men for the extra couple of hours until the rendezvous. It’s to the movie’s credit that all this, crisis piled on top of crisis, doesn’t seem so overdetermined that it becomes comic, even as the inevitable final communications between the seemingly doomed men and their distraught wives pushes the soap-meter into the red.

Everything is overwrought and melodramatic, and yet there are still moments of deliberate professionalism as the technicians stoically work to solve technical and logistical problems … and that’s what I appreciated on seeing the movie again, the dogged efforts of people doing their jobs under extreme pressure. With the trapped astronauts unable to do anything about their situation other than sit there and accept what’s happening, it’s the people on the ground who provide the actual drama.

The image on the disk looks quite good, though hi-def does emphasize the weaknesses in the special effects. There’s a commentary by journalist Bryan Reesman, plus an interview with Kim Newman who situates the film in that transitional period between science fiction and the reality of the space program, and a featurette with C. Courtney Joyner discussing Sturges’ late period movies.

*

Dune (David Lynch, 1984)

I don’t have much to add to what I’ve previously said about David Lynch’s Dune (1984). I bought it yet again – having already bought the massive Koch Media set and Arrow’s 4K edition – because Imprint’s edition includes an extended cut of Daniel Griffith’s retrospective documentary The Sleeper Must Awaken, dropped from the Arrow release due to scheduling issues and rushed to meet the Koch deadline. While only eleven minutes longer, this new version feels much better paced and tells the story of Dune’s transition from book to screen more smoothly. (My only complaint is that my name is still misspelled in the credits.)

Although I long ago swore never to watch the abominable extended television cut again, that version gets a commentary track here from Max Evry, author of the massive oral history of the production A Masterpiece in Disarray, so I did sit through it once again, though the commentary spared me the worst. While Max makes clear how low his opinion of the TV cut is, the extra running time gives him more room to cover the history of Lynch’s movie and the reasons for its many flaws as well as its distinctive positive qualities.

For the rest, the three-disk set includes many of the extras included in previous editions. The one new addition is a brief deleted scene featuring actress Molly Wryn, whose role as Harah, the wife of Jamis who along with her two children becomes Paul’s responsibility after he kills the Fremen, was completely cut from the theatrical release. Lynch had given Wryn a copy of the scene on tape and it’s been restored for this release. In the scene, Harah explains to Lady Jessica (Francesca Annis) that the Fremen are afraid of Alia (Alicia Witt), her monstrous child. Yet another fragment pointing towards the more complex film Lynch shot in Mexico which was fatally damaged by the producers and distributor out of a misguided attempt to make it more “commercial”.

Comments