Fantasy, horror and crazed killers on the exploitation fringes

Among my recent viewing, I’ve seen a number of odd fringe productions about which I knew nothing before ordering them on a whim, or receiving them as part of my Vinegar Syndrome subscription. I know I should be devoting more time to worthwhile art, but can’t seem to escape the pull of low-rent exploitation and the obsessions of hopeful would-be filmmakers toiling in the weeds far from the industry mainstream. Here are just a few of them:

The Black Crystal (Mike Conway, 1991)

The rise of home video in the 1980s opened up a huge market for no-budget movies. While relatively cheap video cameras and the ability to edit on tape made it easy to knock out a feature, talent wasn’t always as readily available, as many a renter frequently discovered after being lured in by VHS packaging which promised far more than the tape inside could ever deliver. In recent years, a great many of these ersatz movies have been unearthed and released on disk by companies like AGFA, Bleeding Skull and Saturn’s Core. Obviously there are enough fans out there to make this a viable business, and I’ve been sucked in perhaps more often than I should admit in my quest to find examples of raw talent among the mountains of dross.

Perhaps it’s the snob in me, but I’m immediately predisposed to be more favourable when one of these movies turns out to have been shot on film, even if the project was completed and released on tape. This is not only because film provides a more pleasing image (this was back before video had improved to today’s hi-def standard); it’s because, by its nature, the use of film imposes a certain discipline on the filmmaker which video doesn’t. Film, with its attendant lab costs, is more expensive than tape, so filmmakers have to be more judicious in their choices, with each shot necessarily thought about in terms of how it will be used in the edit; with tape, you can just let the camera roll and record whatever is happening on set, which is why shot-on-video movies often have a kind of shapelessness – as long as action and dialogue have been recorded, something can be assembled to tell a story even if individual shots are devoid of intrinsic dramatic focus. Video makes it too easy to be creatively lazy, while film forces you to think a bit more about what you’re doing.

But that’s just a technical matter; there’s still the script and acting to consider, and those too often fall short. If there’s one notable shortcoming to Mike Conway’s The Black Crystal (or, as it says on the actual print, The Black Triangle, 1991) it’s the script, which doesn’t fully develop the story’s potential. Which is not to say that the movie, shot on super-8 and finished on tape, isn’t engaging; in fact, it’s good enough that I wished it was just a bit better.

Will (writer-director Conway) is driving through the desert when he picks up a distressed man; he soon discovers why the man is so agitated when a pick-up full of red-necks cuts him off. They drag the man from his car and gouge his eyes out. Will manages to get away and makes it to his brother’s cabin outside a small town. He tries to contact a woman named Daphne (Lily Brown), whom the hitchhiker had mentioned, but she’s initially very hostile. He visits her several times and eventually reveals a crystal he’s found in the car, apparently the object the guys in the pick-up were looking for. Daphne finally opens up and tells him that she and the man in the desert had belonged to a cult run by Daniel (Mark Lang) whose supernatural powers are amplified by the crystal.

We learn that such powers are real when Will is attacked by some local thugs and, on regaining consciousness, he finds them all dead, having been killed at a distance by Daphne. Eventually the couple have to face Daniel and his minions – which is where the script falls short. Rather than a convincing cult compound, we get a ramshackle shed in the desert where a bunch of red-necks hang out drinking beer – a rather dubious representation of a powerful Satanic cult. Although Conway stages an extended action climax with Will taking on the gang and resourcefully dispatching them one by one until only Daniel is left, the magical powers of the bad guys never actually come into play. But despite this failure of imagination, the movie is a tight 70-minute thriller directed with some skill, and with more than adequate performances.

Mastered from the original 1″ video tape, the image on AGFA’s disk is merely adequate, though it does benefit from having been shot on super-8, which gives it a bit more texture than something shot on standard-definition tape. Sound is uneven due to production limitations – wind noise varies from shot to shot. There’s a commentary from Conway, as well as a brief interview with him and actor Mark Lang. Best of all, there are four short films made by Conway more recently on hi-def video, each displaying a playfulness and wit which reveals another side of his talent.

*

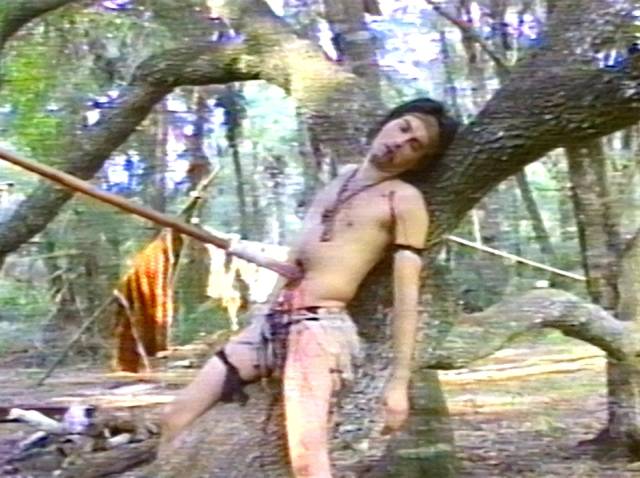

Way Bad Stone (Archie Waugh, 1991)

Shot on video the same year as The Black Crystal, Archie Waugh’s Way Bad Stone (1991) is a very different kind of movie. Made by role-playing gamers and community theatre people, this has the air of enthusiastic amateurs getting together to “put on a show” and, despite a virtually non-existent budget (reputedly $2000), that enthusiasm goes a very long way. I admit I didn’t have high expectations – a sword-and-sorcery epic shot on S-VHS with no money didn’t sound promising (though Michael J. Murphy had been doing similar things with varying degrees of success since the late ’60s) – but this made-in-Florida fantasy has plenty of infectious charm and sincere commitment from everyone involved; production limitations very quickly cease to matter.

After Excalibur (1981) and Conan the Barbarian (1982) proved the commercial viability of this strain of fantasy, there were numerous lower-budget imitations, from Albert Pyun’s The Sword and the Sorcerer and Jack Hill’s Sorceress (both 1982) to a seemingly endless stream of Italian productions throughout the ’80s. By the end of the decade, the vein had been largely exhausted, but that obviously didn’t deter Waugh and his friends. While the script, co-written by Waugh and Jan Kafka, is something like fan fiction (or a Dungeonmaster’s D & D scenario), which initially doesn’t seem terribly promising – the early scenes in the workshop of magician Aladar (Jan Skipper) as he conjures up a woman named Arith (Lisa M. Gallo) seem amateurish and pokey – once things get moving, the story becomes engaging.

Aladar has to leave on a vague mission for the King, leaving Arith in the care of his young acolytes. A band of outlaws get into the workshop looking for a stone of great power, kill the acolytes and kidnap Arith. Aladar summons a collection of warriors loyal to the King to help him get Arith back, a quest which leads to an extended and surprisingly bloody final act. There are some ambitious effects and elaborately-staged action sequences garnished with gore, the whole thing turning out to be far more entertaining than expected.

Having enjoyed Way Bad Stone, I was less surprised to find myself also enjoying the second feature included on the Bleeding Skull Blu-ray. Ionopsis (1997) shares many of the cast and crew with the earlier movie and adds a sci-fi twist to the sword-and-sorcery narrative. Again co-written by Jan Kafka, but directed by Patrick Johnson (who, like Waugh, has no other credits), the script sends a small group of warriors on a mission for some kind of galactic overlord, using a Stargate-like portal to travel to a planet where modern weapons won’t work, in search of a rare orchid. In a forest protected by some anti-technological force, they encounter a magic-based society and the hero eventually comes to side with them against the master who sent him and his team. The pace is a bit leisurely, but the narrative is fleshed out with a fair amount of detail and, once again, the action is quite ambitious given the minuscule budget.

The disk includes two partial commentaries on Way Bad Stone – with director Waugh and producer Jan Skipper. There’s also a short fantasy by Skipper, plus a short film by Waugh which packs in an apocalyptic plague, vampires and a werewolf.

*

Door-to-Door Maniac (Bill Karn, 1961)

Long before home video, such small, low-budget movies had been turned out in large numbers by studio B units; but as the studios declined through the ’50s, this end of the business became the purview of small independent companies producing product for drive-ins and second-run movie houses. For a while, at least, this was fertile ground for filmmakers who wanted to stretch the limits of what was permissible under the Production Code. It was also where you might encounter unexpected surprises, like Bill Karn’s Door-to-Door Maniac aka Five Minutes to Live (1961)

This was the last of three features made by Karn, who had toiled in episodic television during the ’50s, and it starred a pair of familiar faces – Donald Woods, thirty years into a five-plus-decade career which included Eugène Lourié’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), William Castle’s 13 Ghosts (1960) and Henry Hathaway’s True Grit (1969) among twelve-dozen movie and television credits; and Cay Forester, whose career began in the ’40s and included roles in Rudolph Maté’s D.O.A. (1949), Otto Preminger’s Advise & Consent (1962) and Larry Peerce’s Two-Minute Warning (1976). Forester also wrote the script, her sole writing credit. But what makes the movie particularly interesting is that it marked the big-screen debut of Johnny Cash.

In his late twenties, Cash was already a successful performer, crossing over from country to pop, with something of a wild reputation (he was addicted to alcohol and drugs and had had run-ins with the law). As the titular maniac Johnny Cabot, he has an easy charm which slips abruptly into menace and violence. On the run from the law after shooting a couple of cops during a robbery, he ends up in a small city where he’s connected with petty criminal Fred Dorella (Vic Tayback, a couple of decades before hitting it big as diner-owner Mel in the sit-com Alice [1976-85]). Fred has a sure-fire plan for robbing a local bank; he needs a second man to take the wife of one of the employees hostage so that Fred can walk in, make a big “withdrawal” and walk out rich without any trouble. And Johnny seems just the guy for the job. (This is essentially the same plan as in Quentin Lawrence’s Cash on Demand, made in England the same year.)

Door-to-Door Maniac belongs to the suburban home-invasion genre which was quite popular in the ’50s – William Wyler’s The Desperate Hours (1955), Lewis Allen’s Suddenly (1954) – in which the complacency of the middle-class is upended by the intrusion of an external violence which calls into question the assumptions of security on which social stability rests. While money plays an important part in this particular movie, as in others there’s also an edge of sexual menace; the threat to the sanctity of middle-class property extends to the stay-at-home wife.

The movie’s interest lies more in the hostage situation than the robbery itself – the latter is handled perfunctorily, seemingly forgotten for long stretches as the focus remains on the escalating tension between Johnny and Nancy Wilson (Forester) after he insinuates his way into the family home by masquerading as a door-to-door salesman, offering a series of music lessons to justify him carrying a guitar case, which in turn justifies Cash strumming while he waits for Fred to call, either to give the all-clear or to tell him to kill Nancy because the robbery has failed.

Tension is ramped up by intrusive calls from Priscilla (Norma Varden), the wife of Nancy’s husband’s boss, which make it impossible for Fred to call in. There’s also the problem of the couple’s son Bobby (seven-year-old Ron Howard in his big-screen debut), who is due home from school for lunch. It turns out that Johnny has an issue with kids, some kind of traumatic reaction to something in his past which clouds his judgment. But he has no such hang-ups about terrorizing Nancy, taking pleasure in sadistic games like smashing all her treasured ornaments and even firing his pistol and creasing her cheek, all before coming close to raping her as his impatience grows while he waits for the call, fully expecting that he’ll eventually kill her. In fact, he even sings her a menacing song about her having only “five minutes to live”.

After the robbery goes wrong and it looks as if he’ll carry out his violent task, it’s the simultaneous arrival of Bobby and the police that unhinges him – the movie seems to take a very dark turn as he uses the boy as a human shield. With Bobby apparently hit by a cop’s stray bullet Johnny totally loses his grip, and dies ignominiously in the back yard. But the film loses its nerve in the face of such a bleak resolution and pulls back with a laugh as we discover that the smart little boy, having watched a lot of violent TV, has just faked being shot…

Despite pacing problems and the structural issue of seemingly forgetting about the robbery for long stretches, Door-to-Door Maniac is an effectively nasty little B-movie raised a few notches by Cash’s performance. Although he appeared in a number of TV shows and made-for-television movies over the next four decades, he only starred in one other theatrical feature, Lamont Johnson’s A Gunfight (1971), in which he shared top billing with Kirk Douglas.

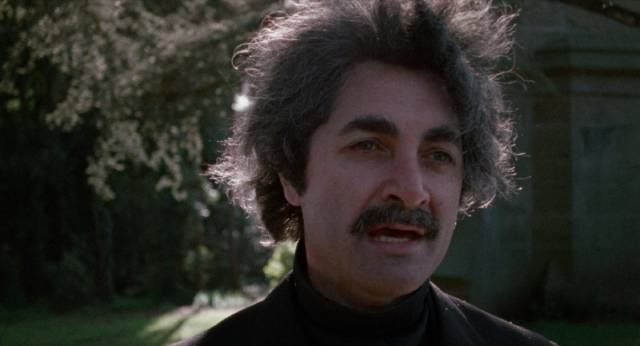

The Film Masters Blu-ray includes a second disk with The Right Hand of the Devil (1963), another low-budget oddity. This was a vanity project by bit-player and Hollywood hairdresser Aram Katcher, a Turkish-born actor whose roles spanned from Napoleon in George Sidney’s Scaramouche (1952) to Tyrone in Russ Meyer’s Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens (1979). In the early ’60s he decided to give himself a lead role in a crime movie, co-writing, producing, directing, editing and doing hair and makeup as well as starring as ruthless criminal mastermind Pepe Lusara, who arrives in Los Angeles in the opening scene in a private helicopter.

Lusara plans to rob an arena box office the morning after a big boxing match. He assembles a team of bickering crooks and seduces the unmarried middle-aged chief cashier (Lisa McDonald), from whom he gets a crucial set of keys. Naturally, things don’t go exactly as planned, but Lusara follows through with his ruthless scheme to get away with all the money by disposing of his crew – and the cashier – after the robbery. But although he gets to relax in Mexico for a while he has made one crucial mistake; he misjudged the cashier, who knew she was being used but didn’t mind until he pushed her off a cliff in her car. Unfortunately for the crook she survived the fiery crash and eventually comes looking for revenge.

As a writer and director, Katcher lacks finesse – his script draws on numerous heist movies like John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950) and Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing (1956), both of which coincidentally starred Sterling Hayden. As a star, Katcher falls short of Hayden’s charisma and authority, but the movie benefits from location shooting and some odd details – Lusara repeatedly sneaks into an industrial building and steals jugs of some liquid which he takes back to his rented mansion and pours into the bathtub; we finally learn what this is for after the robbery when he gives one of his crew an acid bath … while he’s still alive, for an extra horrific frisson.

The disk includes a commentary and a short featurette on the film and Katcher’s career.

*

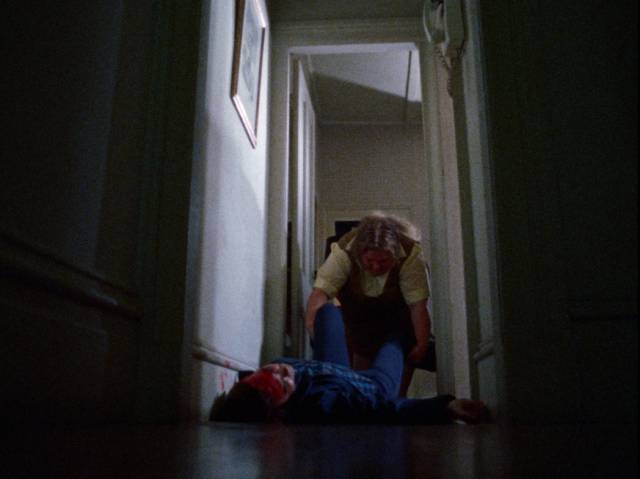

Criminally Insane/Satan’s Black Wedding (Nick Millard, 1975/76)

Nick Millard shares something with John Hayes: both worked on the fringes making exploitation and sex movies, including outright porn, but in the ’70s turned briefly to horror – Hayes with one of my favourites from that era, Grave of the Vampire (1972), and Millard with this pair, restored and released on a double-feature Blu-ray by Vinegar Syndrome. These movies draw on the rough, low-budget, short-schedule production ethos of sexploitation, but replace the sex with violence, blood and occasional supernatural frissons.

Criminally Insane (1975) didn’t seem very promising – a woman with a compulsive eating disorder kills a bunch of people – but turned out to be exactly what I look for in these movies. Cheap, rough, absurd to be sure, but made with a kind of ferocious commitment that overcomes inherent limitations. What lifts it to a whole other level, though, is the remarkable central performance from Priscilla Alden. She plays Ethel Janowski, a perpetually bad-tempered, very overweight woman who’s just been released from a psych ward into the care of her grandmother (Jane Lambert). Perpetually hungry, Ethel is always focused on eating and doesn’t take kindly to being told by everyone that she really needs to cut back and lose weight.

When she discovers that granny has put a padlock on the fridge, she kills the old lady with a big carving knife. Then she phones the local store to place an order; the delivery boy tells her she can’t have the groceries until she pays the bill … so she kills him and stashes him with granny in one of the bedrooms. When a cop (George “Buck” Flowers) comes by to investigate the delivery boy’s disappearance, she manages to brush him off. But then her sister Rosalie (Lisa Farros) shows up looking for a place to stay and ply her trade as a prostitute. Ethel says granny’s gone away for a while and uses a lot of air freshener in an attempt to cover up the smell of the decaying corpses in the bedroom. But Rosalie and her pimp investigate and, discovering the bodies, threaten to get between Ethel and her next meal.

No-one in Criminally Insane is likeable, but Alden manages somehow to get the audience on her side – after all, if they’d just leave her alone and let her eat, nothing bad would happen. Although not played for comedy, she’s a spiritual sister to Divine’s Dawn Davenport in John Waters’ Female Trouble (1974).

I was a bit less taken with Satan’s Black Wedding (1976), mainly because there’s nothing in it to match Alden’s performance. This one belongs to that sub-genre in which someone returns to their small home town only to discover that it has been overtaken by some kind of evil. Two years before it was released, Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz made Messiah of Evil (1974), and half a decade later Gary Sherman made Dead & Buried (1981), while in the year before Millard made his modest horror movie, Stephen King published one of the genre’s masterpieces, Salem’s Lot. Satan’s Black Wedding has a touch of that novel’s vampiric threat as well as Messiah of Evil’s Satanic menace … though on a more moderate scale.

When his sister supposedly commits suicide, Mark Gray (Greg Braddock) returns to a small town on the California coast where he learns that, despite there being a suicide note, the police suspect murder. He reconnects with Jean (Zarrah Whiting), an old girlfriend who had been collaborating with his sister on a book about occult rituals, which seems to have something to do with her death. There’s a church with a sinister priest, a cult planning for the arrival of Satan … and vampires. In fact, his sister is now a vampire as part of Satan’s plan; she has been tasked with killing (and drinking the blood of) her relatives.

Despite the threadbare budget, Millard manages to create some atmosphere and keeps the story moving at a rapid pace – despite bogging down at times with the rekindled relationship between Mark and Jean.

In keeping with the milieu out of which they emerged, both movies run just over an hour, moving briskly so that they never wear out their welcome. It’s interesting, though perhaps not surprising, that Millard should have taken a break from the sex films to make these horror movies – others, like John Hayes and Roberta Findlay, did the same because horror was a viable commercial option at the level on which they were used to working. But these movies didn’t mark a complete change of direction; while Millard did continue to dabble occasionally in horror and violence, his subsequent career was still mostly in sexploitation.

Vinegar Syndrome did extensive work to restore both films from original materials which had sustained severe damage due to poor storage. Considering they were originally shot on 16mm reversal stock, they look quite good – grain is heavy and there’s some colour fading, but they have an authentic grungy appearance which works to their advantage. Each film has an archival commentary from Millard plus a new commentary by film historians. There’s a 48-minute interview with Stephen Thrower covering Millard’s career and these movies in particular, plus archival interviews with Millard and Alden from an earlier DVD edition. Finally, there’s an interesting featurette about the recovery and restoration of the materials, along with a lot of other Millard movies which were recovered seemingly at the point of terminal decay. As a footnote to the documentary included in the Lost Picture Show box set, it reaffirms Vinegar Syndrome’s commitment to preserving these fascinating fragments of cinema history.

Comments