Fall 2024 viewing round-up, part two

Two by Jonathan Demme

I can’t say I’ve ever been much of a fan of Jonathan Demme – other than Stop Making Sense (1984), the greatest concert film ever. There are some enjoyable movies from his early days as one of Roger Corman’s proteges, which led to a couple of quirky comedies in the late ’70s, but nothing that really grabbed my interest. Then he hit it big in 1991 with The Silence of the Lambs, adapted from Thomas Harris’s third novel, and second to feature cannibal serial killer Hannibal Lecter. It’s a mark of Demme’s commercial savvy that he transformed what at its core is another pulp exploitation story into a major A-list award-winner. Its success led to the smugly middle-brow Philadelphia (1993), the first major Hollywood movie about AIDS, which is so self-congratulatory that it hardly needs the appreciation of an actual audience. Demme continued to work until his death in 2017, but never really rose above that level of occasionally pretentious respectability.

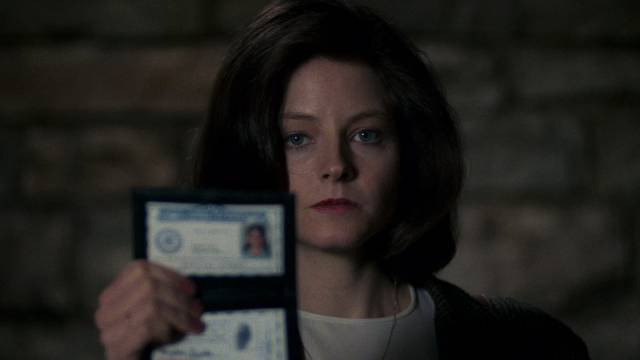

I just revisited The Silence of the Lambs (on Criterion’s 2018 Blu-ray) and had much the same reaction as when I saw it in the theatre in 1991. A polished pot-boiler whose chief point of interest is the centring of a rookie FBI agent named Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster), who is manipulated by both her boss, head profiler Jack Crawford (Scott Glenn), and the charismatic killer Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) as the agency tries to stop another killer nicknamed Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine). The movie’s most radical element is in permitting Starling to be a dedicated professional with no romantic/sexual entanglements. Its less interesting points are its virtually romantic obsession with Lecter, who is portrayed by Hopkins as a cartoonishly seductive figure of pure, enticing evil; and the figure of Bill himself, who drew criticism at the time from the LGTBQ community as a reprehensibly regressive conception of sexual non-conformity. Apparently realizing the problem (but not working to fix it), there’s a line of dialogue which explains that Bill is not actually transsexual, but just thinks he is. Today, this seems to make it even worse as it implies that transsexuality isn’t a real thing but rather a form of delusional mental illness which breeds murderous violence (just imagine if you let these people into women’s washrooms!).

On a less significant note, one other thing which irritates me about the movie is the massive narrative cheat towards the end when cross-cutting is used to mislead the audience as a large, heavily-armed FBI force close in on a house where they suspect Bill is holding his latest victim as Starling makes a routine visit to a remote farmhouse – where naturally Bill opens the door to her knock as the feds kick in the other house’s door. (Criterion’s two-disk set is packed with supplements which to some degree inflate its importance, but do occasionally address its more problematic aspects.)

So why would I bother to watch it again? Because I’d just seen an earlier movie by Demme which I’d never heard of but actually quite enjoyed. Last Embrace (1979) was made between his two quirky comedies, Citizens Band (1977) and Melvin and Howard (1977), marking it as a centrepiece of his shift out of exploitation into the mainstream. Perhaps more than any of his other films at the time, it shows Demme playing with form, consciously evoking the old-school Hollywood romantic suspense of Alfred Hitchcock without much concern for narrative plausibility while leaning into the emotional possibilities of melodrama. The absurdity of the plot is part of the point – it revolves around a series of murders linked by cryptic messages in Biblical Hebrew – with coherence set aside in favour of a series of incidents and encounters which play with various degrees of expectation and surprise.

If Roy Scheider isn’t quite Cary Grant, he nonetheless does a pretty good job as government agent Harry Hannan, who in the opening sequence makes the critical mistake of taking his wife along on a dangerous operation. After she’s killed in cross-fire, he has a nervous breakdown. Released from the psych ward, he finds someone else living in his apartment, a woman named Ellie Fabian (Janet Margolin) who, despite his obvious instability, lets him stay. Harry is an unreliable protagonist, steeped in paranoia which may or may not be justified. He can’t tell who, if anyone, he can trust – including Ellie and his old boss Eckart (Christopher Walken), leading to a big Hitchcockian homage finale at Niagara Falls. The absurdities of the story permit Demme to be more playful than he would later be in The Silence of the Lambs – sometimes knowing you’re working on nonsense can be liberating – and Last Embrace is an enjoyable throw-back to a form which flourished three decades earlier. (The new 4K restoration gets deluxe limited edition packaging from Vinegar Syndrome’s new sub-label Cinematographe, with both 4K UHD and Blu-ray disks, a commentary, a visual essay and an interview with the producer.)

*

Vinegar Syndrome box sets

Speaking of Vinegar Syndrome, they’ve recently released three box sets – two are the latest in ongoing series, the third hopefully the start of a new line.

I had hopes for Home Grown Horrors, which began with a pretty good collection of low-budget regional movies including the amazing Winterbeast and pretty-good Beyond Dream’s Door in volume one, but slipped drastically with three duds in volume two. Now volume three makes a slight recovery with Doug Robertson’s HauntedWeen (1991), yet another movie about a Halloween Haunted House where the customers don’t realize they’re seeing real atrocities. Not too original, perhaps – the murders have their roots in childhood trauma – but Robertson invests some effort into character and suspense.

Less well-crafted, Christopher Lewis’s Revenge (1986), apparently the third part of a trilogy, is ploddingly dull. Patrick Wayne (the Duke’s son) returns to a small town to investigate his brother’s death and teams up with a farmer’s widow to uncover a dog-worshipping cult with roots in Ancient Egypt which is performing human sacrifices and stealing people’s land. The (rather sad) highlight is an aging John Carradine as a politician who’s the head of the cult.

Even duller is Deadly Love (1987), a ghost story directed by Michael S. O’Rourke, whose equally clumsy Moonstalker (1989) was in the second set. A woman inherits a house when her aunt commits suicide and learns that the aunt’s murdered biker boyfriend is still haunting the place. He obligingly takes care of the local jerks who menace the house’s new owner.

Also a little disappointing is volume seven of Forgotten Gialli. This series has been pretty uneven, but has managed to dig up some fairly obscure and occasionally interesting movies – though the definition of “giallo” has been quite loose. Of the three new titles, one is more of a spy thriller, one closer to a social issues movie, and one more like a ’90s made-for-cable “erotic thriller”. The weakest is the first, Carlo Vanzina’s Mystere aka Dagger Eyes (1983), which begins with a political assassination during which a photographer manages to get a shot of the killer. Instead of handing over the evidence, he tries to use it to blackmail the conspirators. Purely by accident, the negative ends up in the hands of a prostitute who doesn’t realize what it is, making her a target of the killers. As bodies pile up, a cop gets involved, seemingly to protect her, though he eventually reveals that he also wants to profit from the photos by selling them to the conspirators.

Obsession: A Taste for Fear (1987) by one-shot writer-director Piccio Raffanini spends a lot of time lingering on naked female bodies since the story revolves around a photographer who specializes in arty porn – which has somehow made her a big celebrity. When her favourite model is brutally murdered, she quickly grabs another nearby hot body and keeps shooting, wasting little empathy on the people around her whom she treats as money-making objects. Naturally, the new model is also killed and the police investigation interferes with her work. The oddest thing about Obsession is a vague attempt to make it futuristic with the cops carrying rayguns and the inclusion of a car which might have served as a model for Elon Musk’s badly designed self-driving Tesla experiments.

Sweets from a Stranger (1987) was the sole directing credit for writer Franco Ferrini, who had worked multiple times with Dario Argento, Lamberto Bava, Michele Soavi and others. While it has some familiar giallo elements – a black-gloved, knife-wielding killer driven by childhood trauma – it spends much of its running time focusing on the prostitutes who are being targeted as they organize themselves because the police aren’t offering them much protection. Its scenes of group meetings in which the women talk about their lives and struggles come closer to a kind of sociopolitical neorealism than straightforward thriller, while the final revelation of the killer’s identity offers an implicit critique of society’s exploitation of economically disadvantaged women.

Of the recent Vinegar Syndrome sets, I most enjoyed Cruel Britannia, a collection of three minor British exploitation movies from the early ’70s. I can’t say these are particularly good, but I did find them entertaining and the settings evoked some nostalgia for the place I came from and had fairly recently left when my family emigrated to Canada shortly before these movies were made. Penny Gold (1973) is the most quotidian of the three, mostly shot around the town of Windsor, west of London, its streets like those of Chelmsford, the nearest town to where I was born east of the capital. Directed by Jack Cardiff, whose reputation as one of the greatest Technicolor cinematographers didn’t translate well to a sporadic directing career, Penny Gold is reminiscent of the old Edgar Wallace Mysteries from the previous decade – or perhaps more appropriately Brian Clemens’ television series Thriller (1973-76). While the mystery is fairly pedestrian – a brutal murder leads the police to the theft of a rare, very valuable postage stamp (an inadvertently amusing McGuffin) – the film opens with a startling giallo-esque murder which raises expectations which remain unfulfilled. The main attraction, apart from the location shooting, is the cast, led by James Booth as the cop, Francesca Annis as the murder victim and her twin sister, Nicky Henson as Booth’s sidekick, supported by well-known character actors Joss Ackland, Sue Lloyd, Una Stubbs, Penelope Keith and John Rhys-Davies, who all help to make the story seem more substantial than it actually is.

Ted Hooker, who had a few credits as editor, wrote and directed only one feature, Crucible of Terror (1971). Essentially a retread of Michael Curtiz’ Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933) and Andre De Toth’s House of Wax (1953), the movie has mad sculptor Victor Clare using real live women as his moulds when casting metal statues – even nastier than Ivan Igor in Mystery of the Wax Museum and Henry Jarrod in House of Wax, who merely dipped already dead bodies into their vats. Unknown to Victor, his debauched son Michael (Ronald Lacey) has been selling his work at inflated prices in a London gallery. When Michael, gallery owner John Davies (James Bolam) and their girlfriends (Mary Maude and Beth Morris) drive down to Cornwall to try to persuade Victor to sell more work, people start to die and eventually his workshop in an abandoned tin mine is revealed to be a chamber of horrors. There’s some rather gruesome business, but Victor is played by DJ Mike Raven in the first of two attempts to establish himself as a horror star (followed the next year by Tom Parkinson’s Disciple of Death); while he had the looks, Raven couldn’t overcome his soft-spoken, mild-mannered personality to make a convincingly dangerous madman.

Directed by Freddie Francis, another superlative cinematographer whose directing credits lack the cachet of the films he photographed, Craze (1974) benefits from a cast which includes some big names as well as some fine character actors in a slightly sleazy slice of grand guignol. Jack Palance, always an enthusiastic scenery-chewer, stars as antique dealer Neal Mottram whose shop cellar houses an African idol which is the focus of a cult he leads, and which requires occasional human sacrifices. The cast is impressive, the story creaky nonsense … but not without interest. Mottram goes to great lengths in his quest for wealth, supposedly guided by the idol Chuku, but it seems more than likely that the sinister figure is actually nothing more than a chunk of carved wood as everything the crazed antique dealer does might have played out exactly the same without any supernatural assistance.

As for that cast, a large roster of notable actors obviously showed up on set for a few hours each to add some class – there’s Diana Dors as a highly-sexed landlady; Dame Edith Evans as Mottram’s wealthy aunt; Hugh Griffith as a venal lawyer; Trevor Howard as a police official; David Warbeck, Percy Herbert and Michael Jayston as the cops investigating Mottram’s murders; Kathleen Byron as a cult member who wants the idol for herself; Martin Potter as Mottram’s business partner and possibly gay lover; and Julie Ege and Suzy Kendall as sacrificial victims. Hard to imagine that kind of talent working on something this low-rent at any other time, but with the British film industry in rocky shape in the ’70s, any paycheque was probably appreciated.

*

Houses of Doom

Being forced to wait for something often makes it more desirable. Cauldron announced their four-disk Houses of Doom box set back at the beginning of the year and put it up for pre-order at the beginning of March … but then a series of production delays kept pushing back the release date and it didn’t finally arrive until early October, a full seven months after I’d paid for it. Was it worth such a long wait? I didn’t actually have high expectations since these four made-for-Italian-television horror movies don’t have much of a reputation, being low-budget projects made late in their directors’ careers. But being a completist, I had to have it and Cauldron’s efforts certainly resulted in a very attractive set, with each movie on its own disk plus two soundtrack CDs.

By 1989, faced with declining health and shrinking budgets, Lucio Fulci’s best days were behind him. After several movies which were a pale reflection of his best work – Aenigma (1987), Zombi 3, Sodoma’s Ghost and Touch of Death (all 1988) – Fulci teamed up with Umberto Lenzi on a TV project to make four movies loosely connected by haunted house themes. The most surprising thing about Fulci’s The Sweet House of Horrors and The House of Clocks is how graphically violent they are – they certainly wouldn’t have been permitted on television in the States or Britain. In the former, after their parents are brutally murdered, two children get new guardians while the ghosts of their parents watch over them. This could have been played for sentimentality, but the kids are obnoxious and the overall tone extremely mean-spirited – the ghosts are not above killing annoying people who want to sell the family home and the kids are happy to laughingly celebrate the interlopers’ violent deaths.

Fulci’s misanthropy is also on display in The House of Clocks, which begins as a home invasion story but quickly becomes a metaphysical nightmare. The old couple in the house have filled every room with clocks and watches which turn out to be more than a collection of antiques when the thieves who break in end up killing the couple and the clocks begin to run backwards, bringing them back to life. But we don’t need to root for the old couple, because we’ve already seen them murder their nephew and his wife, as well as the maid who knows what they’ve done. With time running amok, death is only temporary; people revive in order to kill or die again and, once again, Fulci gets very graphic, so it’s not surprising that neither movie was actually shown on television.

Lenzi’s two contributions aren’t as good as Clocks, which is definitely the best of the lot. In The House of Witchcraft, a man has nightmares of finding himself in a kitchen where a witch is boiling a cauldron on an open fire; she decapitates him and tosses his head into the soup as he wakes up. His wife suggests that they should get away for a rest and they drive to an old house which, unfortunately, is identical to the one in his dreams. Reality and nightmare merge and he no longer knows what is real – did he actually see a priest beaten to death by the witch in the moonlight? The conclusion may not come as a surprise, but Lenzi does create some atmosphere.

The House of Lost Souls might have been a highlight but it’s defeated by characters who do too many stupid things and some obvious production limitations – most problematic is a script which strands its characters due to bad weather and a washed out road despite the fact that it’s shot in dry, sunny weather on clear roads. Supposedly stranded, a group of university researchers who’ve been working in the mountains seek refuge at an old hotel which looks suspiciously deserted. A sinister, silent man lets them in and, with nowhere else to go (on account of the “bad weather”), they settle into the dusty, cobweb-festooned rooms. The best, most startling moment comes when the young brother of one of the researchers is lured to an attic room where he’s killed by a washing machine. It eventually becomes apparent that the hotel was abandoned decades ago after the owner was discovered to be murdering the guests. It’s now haunted by the angry ghosts of his victims who want to kill these new visitors. Since we can clearly see that they could just go somewhere else (it’s not enough to be told that they’re trapped by that “bad weather”), their inability to escape seems absurd – and it’s not helped by their penchant for wandering off by themselves and entering sinister rooms where they’re easy targets for the malevolent spirits.

Despite the movies’ uneven quality, the disks are well-produced, with very good transfers, new and archival cast and crew interviews, and commentaries, plus two soundtrack CDs of Vince Tempera’s scores for the two Fulci films (perhaps Cauldron couldn’t afford to license Claudio Simonetti’s scores for the Lenzi movies). It’s an attractive set and all four movies benefit from being packaged together and given a larger context.

Comments