The 5th Hong Kong International Film Festival, part four

Part four of my notes from the 1981 Hong Kong International Film Festival… and as always I haven’t edited these reviews in any way, although in some cases I no longer agree with what I wrote back then.

4. JAPAN

There was a retrospective of the films (almost twenty of them were screened) of Ozu Yasujiro, a director whose career spanned from the twenties to the sixties, silent to sound, black-and-white to colour. I’m sorry to say I only got to see one of his films – TOKYO CHORUS, a nicely made comedy-drama (silent, 1931). Made with humour and sympathy, it tells the story of a man who loses his job when he confronts his boss on a moral point; it’s the depression and jobs are hard to come by. He gets virtually no sympathy or understanding from his status-conscious wife and his spoilt children. He’s pretty much on his own with his dignity and knowing sense of humour until his faith in others and his unselfishness in friendship pull him through (and teach his wife a slightly better attitude). There’s a touch of slapstick, but the style is remarkably restrained for a silent (it has a quite modern – and Western – look). The comedy is generally very natural, working from little human quirks, the sort of things you normally never notice but which are delightfully familiar when pointed out (the lengthy sequence in which a group of office workers get their yearly bonuses, which spreads into the office washroom, is superbly observed and hilarious).

THE LOVERS’ EXILE is a filmed performance of a Japanese Bunraku puppet play – a Canadian-Japanese co-production directed by Marty Gross, it’s a straightforward, unembellished piece, and a bit dry. The story – of a young man who steals money entrusted to him in order to buy the freedom of the prostitute he loves, and their brief unhappy flight before having to pay the penalty (death for him) – is simple and wistfully romantic; the puppet action is accompanied by music (a single, stringed instrument) and a chanting voice which narrates and provides the dialogue for all the characters. Once you become accustomed to the technique, it’s surprisingly effective – the characters are vivid and clearly differentiated. But it does take a while to get used to it; you see the whole crew of puppeteers up on stage manipulating the figures (though you can tune them out after a while) and the language is harsh and grating (to my ears – and to much of the audience, I believe; I heard complaints, and a number of people left), though when spoken with emotion it becomes very powerful. Gross’ flat and uninspiring direction added to the problem – by occasionally being too selective in his choice of the section of stage we see, and by perhaps too frequently cutting to the sweating, straining chanter – a tactic which served chiefly to distance the puppets, working against the surprisingly human impression they often managed to evoke. A curiosity, not distinctive as film but interesting as a cultural novelty.

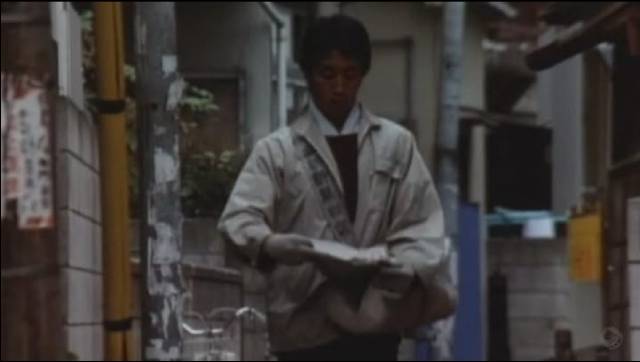

The recent Japanese films were by far the most polished of the Asian group (excluding Tsui Hark’s DANGEROUS ENCOUNTER), but their quality in other areas was quite varied. Yanagimachi Mitsuo’s THE PLAN OF A 19-YEAR OLD starts very well, but runs out of steam long before the end, despite fine acting, an interesting concept, and good production values. The weakness lies in a script which never quite gels into what it could have been. The main character is an aimless youth whose only sense of himself lies in his vague feelings of dissatisfaction and the anger that arises from them. Like Travis Bickle in Scorsese’s TAXI DRIVER, he lives in a crowded city, surrounded by squalor and degradation; like Travis, he sees the people around him not as victims, but as scum – he blames them for the way things are, holds them responsible for his own sense of frustration. Even acts of kindness anger him; he perceives them as condescension, hypocrisy. He draws a map of his paper route, rating his customers, threatening by phone those who earn demerits (which seems to be most of them). He sees himself as a kind of fascist revolutionary, part of an elite which will sweep things clean, a force for restoring order to a chaotic society. His “plan” (the map) becomes ever more detailed, ever more accurate, but since he values nothing, there’s no purpose in it; it never becomes a plan of action. He has only one friend – that is, there’s only one person he differentiates from the crowd; his roommate – and that’s just because he’s the only one the youth is forced into some kind of close contact with. The man is a virtual derelict, burnt out at thirty, who turns thief. The youth sees him as a victim of “them”, just like himself; he blames the man’s girlfriend for his troubles, as the cause of his fall into crime. But when he visits her to accuse her, he discovers a desperate, unhappy wretch; she and the man have been clinging to each other as the only hope against total loneliness. She’s more desperate and frustrated than the youth ever was, and when he tells her she deserves to die, she attempts suicide in front of him. He flees, panicked, the emptiness of his “plan” all too apparent – the enemy he saw isn’t real. He thrashes about in a childish anger, threatening to blow up a train, natural gas storage tanks, but it all just fizzles in the realization of his own impotence – he doesn’t know now who to blame. His plan is no plan because he has no power to act and no target to attack. The ending implies that he manages to shut this out, sinking back into his aimless fantasy…. The film sets up the character quickly and effectively, but then fails to provide any more revelations, as if the director wanted to reflect in the narrative the youth’s stasis, his aimlessness. It goes on repeating its initial observations until any sense of dramatic tension just dissolves.

Oshima Nagisa’s EMPIRE OF PASSION is a visually stunning work which becomes more disappointing the longer you watch it. The material promises a lot: set just before the turn of the century, it tells of a woman and her lover who murder her elderly husband only to be slowly destroyed in turn by a vision of the old rickshawman’s ghost. It has sex, murder, ghosts, and madness, all cast in an unfamiliar setting, a small late-19th century Japanese village – and it comes from a director of some notoriety (his IN THE REALM OF THE SENSES was both hailed as a masterpiece and condemned as pure pornography). So what’s wrong? With a story like this, superb production values, sumptuous photography, it ought to be a marvellous film. Unfortunately, Oshima takes such a cool attitude towards his material, keeps such a distance from it that you might as well be watching a documentary on athletes’ foot. Lust leads to murder, guilt to ghosts, with passion becoming ever more frenzied and ever less of a refuge. But there’s no passion in the telling, no sense of menace. It fails utterly to convey the intensity of the feelings which must have been experienced by these characters. All you’re left with are some touches of macabre humour (the prelude to the murder), one really horrible shock (a blinding with needles), and some very careful, unsalacious sex. A cool and disappointing package.

By far the most successful of the Japanese films I saw was Yamada Yoji’s A DISTANT CRY FROM SPRING – a lovely, gentle, romantic work which takes its time to build up such a thorough emotional involvement with its small group of characters that you’re left feeling nothing but warmth and admiration for the way in which Yamada has touched you (I won’t say “manipulated” – the process is far too subtle and far too positive for such a word to do it justice). The story is simple, involving only three main characters – a widow and her young son struggling to make a go of a farm on the plains of Hokkaido, and a mysterious man who seeks shelter and stays to help. The film, set in a gorgeosly photographed rural area, is full of touches of natural comedy, always arising from character, never imposed. And it sinuously builds up a truly lovely romance – sad, but never sentimental (the Japanese restraint of feeling makes it all the more moving; the couple only touch once, the woman’s only open revelation of the feelings she holds for the man). The sad/happy ending, with the past being paid off, making way for a new future for the characters, leaves you with a desire to linger, basking in the warmth. I can’t think of any other film which handles such feelings with quite such an unobtrusive skill. I loved it – without any reservations whatever.

Comments