The 5th Hong Kong International Film Festival, part seven

More of my notes from the 1981 Hong Kong International Film Festival… and as always I haven’t edited these reviews in any way, although in some cases I no longer agree with what I wrote back then.

7. WESTERN EUROPE

YOU ARE NOT ALONE, a Danish film directed by Lasse Nielsen and Ernst Johansen, is a pleasant little film set in a boys’ boarding school. Its subject, as the directors put it, is the “rich and full emotional life of children” – which is ignored or misunderstood by adults. Against an often entertainingly observed school-days background, the friendship of two boys blossoms into a full emotional relationship, an innocent homosexuality untainted by the societal imprint of vice. It’s all handled with humour, sensitivity, a lack of sentimentality, impeccable taste – and best of all an absence of didacticism; it never becomes a commercial for the joys of homosexuality. On top of which it’s nicely photographed in bright summer tones.

TIRO, from the Netherlands, directed by Jacob Bijl, is the beautifully filmed story of a teenager who refuses to “grow up”. He despises what appears to be adult reality – the hypocrisy, the obsession with money which causes his elders to sell out what seems most valuable, the constant compromises that have to be made. The boy is a romantic (with the accompanying air of gloom); he doesn’t want to think, to deal with the complications which come with responsibility; he just wants to be – most particularly in his beloved marshlands where he hunts (with a respect for his prey absent in most of his elders) and communes with nature. His cynical elder sister (superbly played by Geert de Jong) encourages his romanticism – as something she loves but is unable to share – and foments clashes with their unimaginative, business-minded (but quite ordinary, not evil) father. The film follows the realization that the father is selling the beloved marshes to a developer, and the boy’s refusal to compromise his perception of this as an irredeemably despicable act. Ultimately unable to come to terms with this less than perfect world, he commits suicide – rigging it so that his sister, whose encouragement has at least in part led to his destruction, is the one who “pulls the trigger”. The country in which the film is set is filmed with such loving care that you can almost identify with the boy despite his sullen stubbornness – but it is the sister who really takes your attention; she has too much imagination to settle into the blinkered provincial society around her and too clear a vision to be able to deny it completely as her brother does; she’s more lost than he, and without the compensation of an obsessive passion.

Fellini’s LA CITTA DELLA DONNE (CITY OF WOMEN) has not been well received by the critics. In fact, one went so far as to say it just proves that Fellini doesn’t have anything to say – and has had nothing to say since LA DOLCE VITA; and further, that the only people who could consider him a great director are those without a brain, who are impressed by pretty pictures. Leaving aside the personal insult – there are different ways of “saying” things. Fellini was never an intellectual director (and anyway film as a medium works against intellectualism – its first and most powerful effect is an emotional one); he’s an emotional director. He works with feelings (which is why the feelingless CASANOVA, one of his most visually beautiful works, is such a tedious waste of time). I’m not saying that feelings are more important than ideas – they’re just more important in Fellini’s films. If he never reaches an intellectual point, it’s because he’s not making an argument – he’s just romping energetically through his feelings about things. It’s self-indulgent, egotistical, not necessarily even original (the case with LA CITTA). But he is a dazzling showman – so I feel no need to apologize for liking his films. When was the last time someone came along with an original circus? but people still go and enjoy. Anyway, LA CITTA is Fellini’s fantasia on the female, an overblown tour of comic/grotesque attitudes, in search of the true essence. It starts from dogma – militant feminism, hatred of the male – goes through Don Juanism – the equally dogmatic possessive reduction of woman to object – to the state of “war” to which these extreme attitudes have brought relationships between the sexes. It’s the journey of Snàporaz, a middle-aged man (Mastroianni as Fellini) who has a vast undefined passion for women, and who is totally confused by all these extremes. A string of bizarre encounters – male/female, fear/hate, lust/love – a bit soggy in the middle with some scenes going on too long, but full of a bemused affection lit at times by dazzling Fellini imagery. And if the “conclusion” isn’t exactly an original insight (the essence is ungraspable, the mystery is what makes life a pleasure), the trip has been fun.

Maurice Pialat’s LOULOU (the only French film I saw at the festival) is a beautifully crafted piece of “poetic realism”. It’s about the way relationships fade with time. Isabelle Huppert’s marriage to the intensely jealous Guy Marchand has become a bore, a predictable round of arguments and atonement. She walks out and moves in with Loulou (Gérard Depardieu) – he’s unemployed, doesn’t mind a bit living off her earnings – but he’s new and fresh, physically exciting. Their relationship begins in passion, full of newness and hope. But gradually it slips, almost without their noticing, into habit. It acquires doubt, distrust, loses its joy – and settles into the predictability from which the woman fled at the start of the film. It’s superbly acted – every gesture, every expression and tone of voice is perfect, seems completely un-acted – I can’t recall another film in which the characters seemed quite so convincingly real. And it’s all carefully observed by Pialat, who remains unobtrusive throughout. Though it seems to become a little slack towards the end as the couple’s doubts increase – as if Pialat couldn’t quite lick the problem of maintaining interest while showing the rise of boredom….

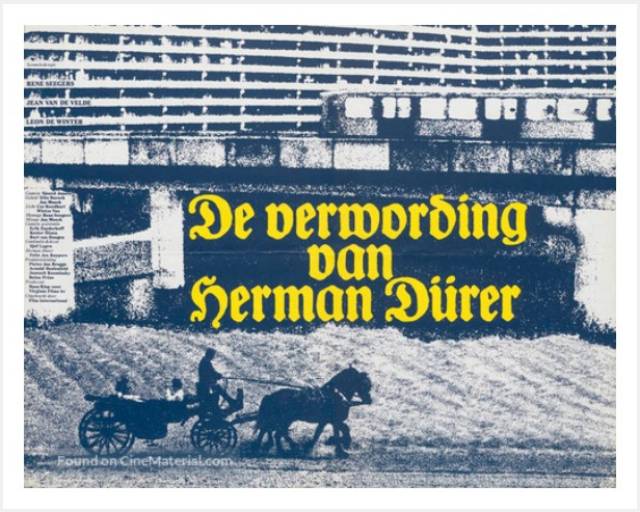

THE DEMISE OF HERMAN DÜRER, a Dutch film directed by René Seegers, Jean van der Velde, and Leon de Winter, takes a little while to find its stride, but once it finds it, it doesn’t put a foot wrong. It’s an effective, finally sad and moving film about aimlessness and how out of place the Romantic imagination is in an urban, industrialized world. Herman’s dissatisfaction with city boredom, the pursuit of money, production-line jobs, first takes the form of petty crime. But in juvenile prison he discovers a 19th century book, Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts (from the life of a good-for-nothing); he reads it avidly and comes to identify with its hero, a carefree wanderer from a past age. He sets out to follow his hero’s footsteps – and sees in his own encounters reflections of those described in the book. But the more he identifies with the book, the further drab reality moves from the dream. At last he encounters the book’s heroine – that is, a girl who has read it, thinks it’s fun and briefly plays her part in his fantasy – but she refuses to carry the play past a brief game and rejects Herman when he tries to insist that they live out the book together. At which point he cracks; his real and dream personae converge in a state of confusion – and in that confusion he strikes out and commits an aimless murder (a taxi driver who refuses to drive him to Italy) and flees completely into his fantasy past. The torment of longing for an undefined something other is depicted with power, sympathy and understanding. It’s a marvellous film.

Comments