The 5th Hong Kong International Film Festival, part three

More of my notes from the 1981 Hong Kong International Film Festival… and as always I haven’t edited these reviews in any way, although in some cases I no longer agree with what I wrote back then.

3. INDIA & PAKISTAN

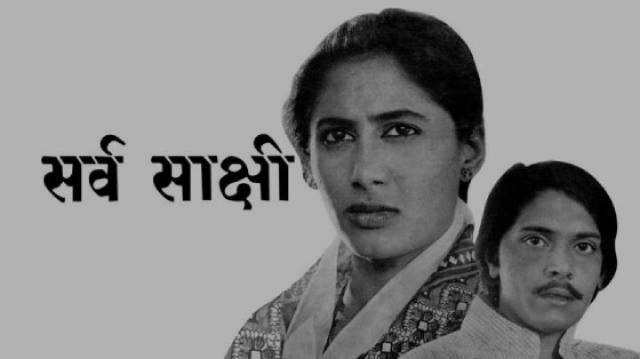

From India, three films. THE OMNISCIENT (SARVASAKSHI) is the first film of writer/director Ramdas Phutane. Technically very rough – poor film stock, harsh, unclear sound – too long, becoming dramatically weak in the second half as it plods when it should be building to a revelation – but interesting in subject matter, if not terribly original. A young teacher and his wife arrive in a remote village; he’s a rationalist who has no time for local superstitions – in fact, he’s so rational his mind is cut off from the spiritual forces (if you will) which lie beneath the material surface of the world. Opposite him is the bhagat, the local medicine man who manipulates superstition – and perhaps actual forces – for those who can pay, but mostly just to give himself personal power over the locals. A series of ritual child murders occurs, and suspicion falls on the teacher. The real culprits are finally caught – but not until after the teacher has come to admit the reality of a Truth larger than his limited rationalism. Both faith and science are paths to Truth, says Phutane, but neither is Truth itself, and either when held to be exclusive of the other and an end in itself will result in a dangerous blindness. The film’s chief problem lies in Phutane’s inability to exploit the “mystery” for even a modicum of suspense – there is very little in the way of simple drama to carry more than two hours of film. And, as usual, the subtitling was atrocious – you got the impression that you were missing out on a number of probably significant conversations.

Somewhat more proficient, but still too long (though luckily devoid of the almost obligatory Indian musical number – that even turned up in THE OMNISCIENT), T.S. Ranga’s SAVITHRI – THE WIFE is an interesting film with some parallels to Phutane’s film, but without the supernatural overtones and perhaps a bit more difficult for a non-Indian to identify with. Again we have a young teacher arriving in a remote village and running afoul of local ways. This time, though, he’s a bachelor. He gets caught in the middle of a long-standing feud between two village elders. He is persuaded by one to marry the daughter of the other – in order to do which he must go along with a kidnapping. This is the main problem; going along with the plan seems so stupid that it’s hard to believe, and virtually impossible to sympathize with. But that hurdle crossed, and the rest is very interesting. The perpetrator of the plan manages to persuade the teacher to take the rap alone. So the girl’s father is humiliated by the marriage to a man of unequal caste, and frustrated in his attempts to punish the real villain. The girl has a baby, making it difficult to marry her off again (a court pronounced the marriage invalid). But someone finally agrees to take her; she refuses, waiting for the teacher to return from prison; he does – the father takes him aside. And kills him. The teacher is destroyed, the girl ruined, the father humiliated and perhaps brought down entirely – and the perpetrator is left untouched. The whole thing is a master stroke in a petty feud whose origins have long been lost in the subjective blur of different memories.

One obviously shouldn’t make generalizations based on such skimpy evidence, but from these two films it seems that there is a tendency in Indian cinema to “bloat”; what should be short and sharp and to the point is instead drawn out and so slowly paced that it loses much of its potential edge. In both these films the direction isn’t particularly imaginative, relying for effect almost entirely on the story which takes too long to unfold. And the main characters are too passive to create a genuinely tragic feeling.

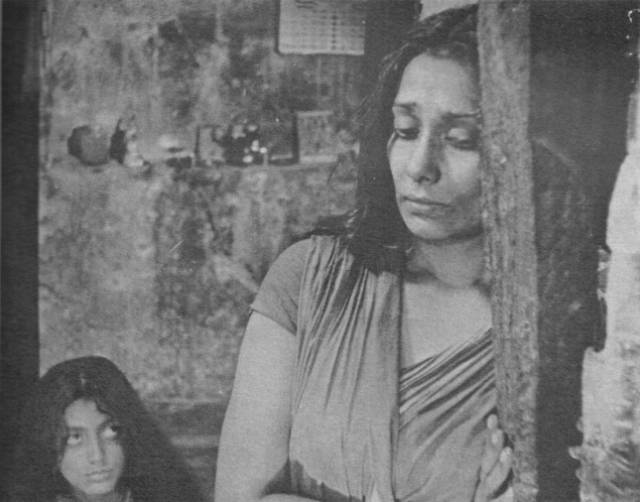

Passivity also hangs over BITTER MORSEL (NEEM ANNAPURNA) by Buddhadeb Dasgupta. But it is a passivity brought on by hopelessness, of people who have given up. This taut little film belies my other points above. Short and stark, it’s an exercise in DeSica-like realism, a slice of slum life cut with such an air of authenticity that it leaves you feeling rather helpless. It’s not laced with all those layers of irony which enriched BICYCLE THIEVES, but to a large degree that brings the sheer awfulness of what is shown that much closer. In a completely unsentimental way, it depicts a few days in the lives of a slum family in Calcutta, living in utterly unrelieved poverty, scraping by day to day. The husband can’t find work; he has TB. The mother hangs on to her caste identity, refusing to allow the eldest daughter to work because it would be too demeaning. Next door (or rather, next hovel) lives a sick old man, an untouchable shunned by the wife. Finally, desperate, she sneaks into his room to steal his rice; he returns; they struggle – and he collapses, dead. She takes the rice back to her hovel and cooks it for her family – but can’t eat it herself. It’s a pitiful film, one which would have been intolerable in less certain hands. Dasgupta seems to know exactly what distance to keep as he shows these people trying to hang on to their last shreds of dignity in a situation which both they and we know is hopeless – they’re condemned, never to escape from the place to which they’ve sunk….

Perhaps surprisingly – but then again, perhaps not – the festival’s Pakistani film was a far more polished piece of work. Pakistan? Well, actually Jamil Dehlavi, the writer/director, has lived some time in England (and is self-exiled there now) – and this bilingual film was largely financed with English money. It’s a curious piece of work. About oppression and the struggle against it, it’s so busy making a moral (religious) point that it neglects almost entirely its political-thriller aspects. Curiously, most of the moments which aspire to emotional impact result in a negative effect. Moving at too slow a pace, its narrow story follows Hussain as he goes from being uninvolved to being defiant and finally to being a martyr. A military coup has taken place (his brother joins the new regime) and his efforts to stand apart are embarrassing the new powers that be; asked to knuckle under, he refuses; his estate is attacked. The only straightforward piece of gut-level action in THE BLOOD OF HUSSAIN occurs here, as he arrives in the nick of time to kill some soldiers who are about to shoot his pregnant wife. The problem: while we see a number of instances of the oppressors’ brutal inhumanity, the only action taken by Hussain – presented as a great leader – (apart from saving his wife) is to smear his face with his baby son’s blood and walk into the bad guys’ bullets. There’s something to do with passive resistance here, the uniting power of martyrdom – the film ends with crowds inspired by the death of Hussain. But those final images repeat images from the film’s opening: the story is based on an event from over a thousand years in the past, the martyrdom of another Hussain who stood against an oppressor. Today, we are shown, people flagellate themselves into a bloody mess in memory of that event. The film ends with new flagellants whipping themselves into bloody hysteria in the name of the new martyr. Now, apart from the fact that it seems a particularly ineffective way to defeat oppression (beat yourself to a pulp and thus scare the dictator out of office?), surely this repetition of images defeats the director’s purpose? Hussain’s martyrdom has been to no purpose; the oppressors have been around unchanged for thousands of years; their victims wail on helplessly against the oppression – nothing has changed. Dehlavi seems so wrapped up in telling the old tale in modern dress that he’s supplied no way out. The result is frustrating, emotionally dissatisfying – we see Hussain quite deliberately run himself into a blind alley, quite deliberately get himself killed, consciously choosing martyrdom (and that always puts me off because of the implicit conceit) – and all to no political purpose. An air of futility is what remains after it ends. But long after all the murky Islamic thought has faded, and the dramatic weaknesses, and the annoying tics exhibited by Salmaan Peerzada as Hussain (and his slightly overstuffed performance as Hussain’s twin brother) – long after all that has gone, one thing will remain, fixed clearly in my mind: the image of a powerful white stallion literally rising from the desert sands, bursting up through the ground in slow motion, a symbol of Hussain’s mystical, god-given power. It’s one of the most startlingly beautiful moments I’ve ever seen.

Comments