Fellini’s 8½ (1963): Criterion Blu-ray review

It was through Fellini’s 8½ (1963), indirectly, that I was introduced to the idea of the “foreign art film”, an idea which implied both a higher cultural position and intellectual pretension, not to mention an element of upper class refined taste. This was when I was nine years old and I can actually pinpoint the exact date: February 4, 1964. That was the date that the fifth episode of the third season of the BBC comedy series Steptoe and Son (1962-74) aired on a Tuesday evening. In that episode, son Harold (Harry H. Corbett) argues with his cranky father Albert (Wilfred Brambell) about what movie to go see. Albert wants the lowbrow Nudes of 1964, but Harold, wanting to appear more sophisticated, votes for 8½. As I recall, they each buy their ticket, but Harold quickly realizes the Italian film is no fun at all and ends up sneaking into the other theatre to join his father watching what is obviously a mondo parade of naked women.

It was through Fellini’s 8½ (1963), indirectly, that I was introduced to the idea of the “foreign art film”, an idea which implied both a higher cultural position and intellectual pretension, not to mention an element of upper class refined taste. This was when I was nine years old and I can actually pinpoint the exact date: February 4, 1964. That was the date that the fifth episode of the third season of the BBC comedy series Steptoe and Son (1962-74) aired on a Tuesday evening. In that episode, son Harold (Harry H. Corbett) argues with his cranky father Albert (Wilfred Brambell) about what movie to go see. Albert wants the lowbrow Nudes of 1964, but Harold, wanting to appear more sophisticated, votes for 8½. As I recall, they each buy their ticket, but Harold quickly realizes the Italian film is no fun at all and ends up sneaking into the other theatre to join his father watching what is obviously a mondo parade of naked women.

For some reason, even though I was too young to fully understand the class-based satire, this stuck with me and for a long time 8½ represented the cinema of snobs, a movie which could be wielded as a symbol of intellectual superiority over the more ignorant masses who were obviously ill-equipped to understand it. Strangely, although that childhood memory has remained vivid for six decades, I don’t recall when I actually saw 8½ for the first time, though I suspect it was sometime during the ’70s on television. I may have been baffled, even intimidated; I probably wasn’t fully equipped to decipher its dense mix of dreams, childhood memories and bourgeois angst evoking the crippling effects of insecurity on an artist’s compulsion to create. But as I myself evolved and returned to the film repeatedly in the ensuing years, it has exerted an almost hypnotic fascination and taught me a great deal about the art of cinema.

For some reason, even though I was too young to fully understand the class-based satire, this stuck with me and for a long time 8½ represented the cinema of snobs, a movie which could be wielded as a symbol of intellectual superiority over the more ignorant masses who were obviously ill-equipped to understand it. Strangely, although that childhood memory has remained vivid for six decades, I don’t recall when I actually saw 8½ for the first time, though I suspect it was sometime during the ’70s on television. I may have been baffled, even intimidated; I probably wasn’t fully equipped to decipher its dense mix of dreams, childhood memories and bourgeois angst evoking the crippling effects of insecurity on an artist’s compulsion to create. But as I myself evolved and returned to the film repeatedly in the ensuing years, it has exerted an almost hypnotic fascination and taught me a great deal about the art of cinema.

Fellini’s signature film is a paradox, an exuberant, endlessly inventive 139-minute exploration of creative paralysis. Not simply a movie about the endless struggles a director faces when making a movie, it is more deeply self-referential – an imaginative depiction of Fellini’s own struggle to make this particular film in the face of self-doubt. After the enormous international success of La dolce vita (1960), he faced two of the biggest problems an artist might encounter; external pressure – from producers, critics and a potential audience waiting to see if he could top that previous achievement – and the internal pressure to find something to say which would make the effort worthwhile.

Fellini’s signature film is a paradox, an exuberant, endlessly inventive 139-minute exploration of creative paralysis. Not simply a movie about the endless struggles a director faces when making a movie, it is more deeply self-referential – an imaginative depiction of Fellini’s own struggle to make this particular film in the face of self-doubt. After the enormous international success of La dolce vita (1960), he faced two of the biggest problems an artist might encounter; external pressure – from producers, critics and a potential audience waiting to see if he could top that previous achievement – and the internal pressure to find something to say which would make the effort worthwhile.

Fellini opens the film with an evocative dream (nightmare) sequence which expresses those tensions in purely visual terms. His on-screen surrogate Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni) is stuck in a traffic jam in a tunnel, cars bumper-to-bumper with the bright light of the tunnel entrance unreachable ahead. Around him, the occupants of those other cars and a bus stare at him and he begins to panic. Toxic fumes begin to fill his car, but he can’t open the windows or doors; he kicks at the glass impotently as he suffocates, but then manages to climb up through the sunroof, floating above the cars towards the light … and then, in one of those shifts to which dreams are prone, he’s floating high above a beach, a rope tied to his ankle inhibiting his flight. Far below, people pull on the rope and he plunges towards the point where waves wash against the sand … and abruptly wakes in a bed surrounded by medical staff who are poking and prodding him as his producer comes in to check on his condition.

Fellini opens the film with an evocative dream (nightmare) sequence which expresses those tensions in purely visual terms. His on-screen surrogate Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni) is stuck in a traffic jam in a tunnel, cars bumper-to-bumper with the bright light of the tunnel entrance unreachable ahead. Around him, the occupants of those other cars and a bus stare at him and he begins to panic. Toxic fumes begin to fill his car, but he can’t open the windows or doors; he kicks at the glass impotently as he suffocates, but then manages to climb up through the sunroof, floating above the cars towards the light … and then, in one of those shifts to which dreams are prone, he’s floating high above a beach, a rope tied to his ankle inhibiting his flight. Far below, people pull on the rope and he plunges towards the point where waves wash against the sand … and abruptly wakes in a bed surrounded by medical staff who are poking and prodding him as his producer comes in to check on his condition.

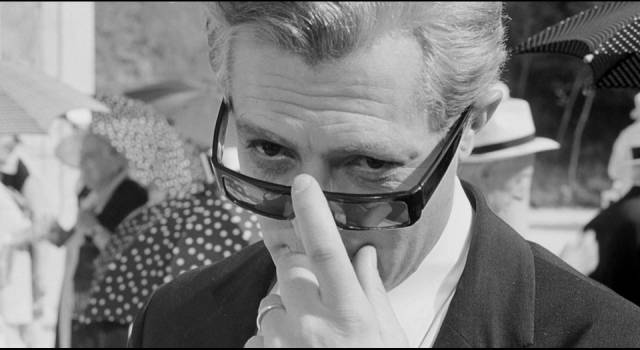

Guido isn’t actually in hospital, though; he’s at a spa where he’s supposed to be relaxing and taking the healing waters as he plans his new film. But it’s impossible to relax because there are endless demands for him to make decisions as the start of shooting approaches. Actors press him for details about the characters they’re to play, but he brushes them off because he doesn’t actually know what he wants. A writer to whom he’s given the script tells him it’s trite rubbish which says nothing. And always there are people praising his work and raising expectations about the new project. Trying to block out the constant noise, he fantasizes about a beautiful, aetherial woman who seems to drift weightlessly through the grounds of the spa, offering him a glass of the healing waters. She’s played by Claudia Cardinale, who will later turn up as the actress Claudia, asking him about the character she’s to play in the new film – even his dreams bend back towards the perplexing problems facing him.

Guido isn’t actually in hospital, though; he’s at a spa where he’s supposed to be relaxing and taking the healing waters as he plans his new film. But it’s impossible to relax because there are endless demands for him to make decisions as the start of shooting approaches. Actors press him for details about the characters they’re to play, but he brushes them off because he doesn’t actually know what he wants. A writer to whom he’s given the script tells him it’s trite rubbish which says nothing. And always there are people praising his work and raising expectations about the new project. Trying to block out the constant noise, he fantasizes about a beautiful, aetherial woman who seems to drift weightlessly through the grounds of the spa, offering him a glass of the healing waters. She’s played by Claudia Cardinale, who will later turn up as the actress Claudia, asking him about the character she’s to play in the new film – even his dreams bend back towards the perplexing problems facing him.

As he avoids the constant demands of his collaborators, Guido seeks distraction by complicating his personal life. He’s invited both his mistress Carla (Sandra Milo) and his wife Luisa (Anouk Aimée) to join him at the spa, and spends energy juggling the pair in a futile effort to conceal each from the other. Carla chatters endlessly, while Luisa is reaching the limits of her patience, well aware of her husband’s affair(s). These two women lead into a complicated mix of dreams, fantasies and memories revolving around sex and the inability for a man to fully comprehend the nature of women (a recurring theme in Fellini’s work).

There’s his boyhood experience of slipping out of school with his friends to visit a woman named La Saraghina (Eddra Gale) who lives on the beach, her huge, heavy body exuding an erotic charge as she dances for the boys … only to be interrupted by the priests who run the school arriving to drag the boys back for a punishment which will instill a sense of guilt about sexual desire. Guido will internalize that guilt and carry it with him into adulthood. There’s a lengthy fantasy in which he finds himself surrounded by all the women in his life, past and present; the setting is a kind of domestic harem and he tries to control them all (actually wielding a whip), but is eventually overwhelmed, rendered impotent by the power they have over him.

There’s his boyhood experience of slipping out of school with his friends to visit a woman named La Saraghina (Eddra Gale) who lives on the beach, her huge, heavy body exuding an erotic charge as she dances for the boys … only to be interrupted by the priests who run the school arriving to drag the boys back for a punishment which will instill a sense of guilt about sexual desire. Guido will internalize that guilt and carry it with him into adulthood. There’s a lengthy fantasy in which he finds himself surrounded by all the women in his life, past and present; the setting is a kind of domestic harem and he tries to control them all (actually wielding a whip), but is eventually overwhelmed, rendered impotent by the power they have over him.

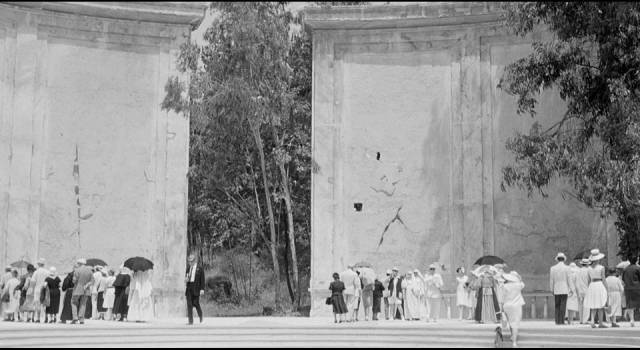

Meanwhile, the demands continue – he’s caught in a screening room watching screen tests of various actors as those around him demand firm decisions about casting (decisions he’s unable to make because he himself doesn’t know the characters in his own script); he visits a vast outdoor set under construction, a massive frame of scaffolding suggesting the shape of a spaceship yet to be built, a visual analogue of the unmade film itself – and of 8½ – as a vague suggestion which is missing all the concrete details which will give flesh to the filmmaker’s creative endeavour.

While the film expresses Fellini’s own uncertainties and anxieties about his work, what is remarkable about 8½ is the way it so fully and successfully succeeds in filling in all those details. By plunging headlong into those uncertainties, Fellini managed to make what may be his most fully realized film, finding a way through and out of creative paralysis by finally embracing the chaotic mess and contingency of life, evoking in the final sequence his love of the circus as a metaphor for that chaos given form. Everyone involved in the film gathers at the end around that unfinished spaceship rising from the wasteland, cast, crew, critics, lovers joining hands and dancing as the boy Guido leads a ragtag band playing Nino Rota’s exuberant theme. Guido escapes his solipsistic anxieties by embracing life outside of his art … and in doing so allows Fellini to fully express his own art.

While the film expresses Fellini’s own uncertainties and anxieties about his work, what is remarkable about 8½ is the way it so fully and successfully succeeds in filling in all those details. By plunging headlong into those uncertainties, Fellini managed to make what may be his most fully realized film, finding a way through and out of creative paralysis by finally embracing the chaotic mess and contingency of life, evoking in the final sequence his love of the circus as a metaphor for that chaos given form. Everyone involved in the film gathers at the end around that unfinished spaceship rising from the wasteland, cast, crew, critics, lovers joining hands and dancing as the boy Guido leads a ragtag band playing Nino Rota’s exuberant theme. Guido escapes his solipsistic anxieties by embracing life outside of his art … and in doing so allows Fellini to fully express his own art.

That art provides a masterclass in filmmaking. In sequence after sequence, Fellini uses the camera to convey the constant shifts in Guido’s psychological and emotional state, from that opening dream to the carnivalesque conclusion. From a purely filmmaking point of view, I find the sequence in the grounds of the spa particularly fascinating. With few cuts, Fellini uses framing, camera movement and blocking to constantly shift the viewer’s attention, creating and shifting connections among the characters to evoke dynamically the endless flow of social relationships which Guido – and by implication, members of the audience – must navigate as he (and we) moves through life.

That art provides a masterclass in filmmaking. In sequence after sequence, Fellini uses the camera to convey the constant shifts in Guido’s psychological and emotional state, from that opening dream to the carnivalesque conclusion. From a purely filmmaking point of view, I find the sequence in the grounds of the spa particularly fascinating. With few cuts, Fellini uses framing, camera movement and blocking to constantly shift the viewer’s attention, creating and shifting connections among the characters to evoke dynamically the endless flow of social relationships which Guido – and by implication, members of the audience – must navigate as he (and we) moves through life.

In breaking through his creative block in 8½, Fellini freed something in himself and after this he abandoned the influence of neorealism which had left its traces in all of his previous work. After 8½, he made his first colour film, the phantasmagoric Juliet of the Spirits (1965), which embraces the mix of dreams and memories to provide something of a companion piece focused on a wife breaking free of an unfaithful husband. This was followed by the even more fantastical Toby Dammit (his segment of the portmanteau Spirits of the Dead, 1968) and Fellini Satyricon (1969), which rejects the modern world altogether in its depiction of ancient Rome as a kind of polymorphously perverse wonderland. And everything which followed embraces that exuberant carnivalesque view of life in all its messy complications. What we see in 8½ is an artist decisively creating himself and finding the voice which most clearly expresses his view of the world.

In breaking through his creative block in 8½, Fellini freed something in himself and after this he abandoned the influence of neorealism which had left its traces in all of his previous work. After 8½, he made his first colour film, the phantasmagoric Juliet of the Spirits (1965), which embraces the mix of dreams and memories to provide something of a companion piece focused on a wife breaking free of an unfaithful husband. This was followed by the even more fantastical Toby Dammit (his segment of the portmanteau Spirits of the Dead, 1968) and Fellini Satyricon (1969), which rejects the modern world altogether in its depiction of ancient Rome as a kind of polymorphously perverse wonderland. And everything which followed embraces that exuberant carnivalesque view of life in all its messy complications. What we see in 8½ is an artist decisively creating himself and finding the voice which most clearly expresses his view of the world.

*

The disk

Criterion’s dual-format edition of 8½ uses a new 4K restoration which serves Gianni Di Venanzo’s black-and-white cinematography well, with richly layered contrast and a great deal of fine detail. The restored mono soundtrack is also excellent.

The supplements

There are no new supplements, other than critic Stephanie Zacharek’s booklet essay, which is a pity as in the quarter century since these disk extras were first included in Criterion’s 2001 DVD edition, Fellini’s reputation has gone through various fluctuations and a reassessment of this particular film might have been illuminating. What we do get are all the original DVD supplements, beginning with a composite commentary from film critics Gideon Bachmann and Antonio Monda. There are more than three-and-a-half hours of documentaries and featurettes, beginning with an admiring introduction from Terry Gilliam (7:30). An NBC documentary (1969, 51:16) treats Fellini and his work with the same kind of surreal approach as he uses in his own films; there’s a lengthy examination of the film’s original ending (50:24), which was downbeat, with a suggestion of suicide, abandoned at the suggestion of co-writer Tullio Pinelli and replaced with the more celebratory conclusion which was actually shot by Fellini as a trailer; a 1993 German TV documentary surveys the career of composer Nino Rota (47:28). There are interviews with actress Sandra Milo (26:37), assistant director Lina Wertmuller (17:28), and Vittorio Storaro (17:24), who discusses the work of cinematographer Di Venanzo. There are galleries of production photos by Gideon Bachmann, plus a trailer (3:09) and Zacharek’s booklet essay.

Comments

8 1/2 and La Dolce Vita were the first 2 Italian movies I added to my collection, many, many years ago. Later came other films like The Bicycle Thief and Umberto D.

Thanks for the great review. As always, it was more than a pleasure to read.

Hi Kevin, Happy New Year!

Happy New Year Kenneth!

I’m looking forward to reading your new reviews throughout the year. I tell everyone I know that your reviews are among the best I’ve ever read. It’s amazing to me that some big city newspaper hasn’t snatched you up to be their reviewer!

I don’t think I’m cut out for that – staff reviewers generally have to cover current releases rather than the random selection I’m prone to, and I wouldn’t enjoy writing about something that someone has assigned me to. Plus I don’t enjoy dealing with editors!