The 5th Hong Kong International Film Festival, part eight

More of my notes from the 1981 Hong Kong International Film Festival… and as always I haven’t edited these reviews in any way, although in some cases I no longer agree with what I wrote back then.

8. GERMANY

Of the six German films I saw, which ranged from very good to very bad, the worst was Claudia von Alemann’s DIE REISE NACH LYON (BLIND SPOT), a film which relies solely on its feminism for a defence – you can easily picture the writer/director answering any criticism with a stark “you’re anti-feminist”. But the simple, unavoidable truth is: the film is slow, dreary, and pretentious. It’s about a dull, vacuous woman with nothing better to do than to follow a romantic desire to be somebody notable in another time (a crusading 19th century feminist), all the while disguising it as a non-personal, historically oriented search for some meaningful feminist experience. Personally, I felt certain that the earlier woman would have seen our heroine’s angst as the utterly trivial ennui of the privileged. From the slight glimpses we get of that early feminist (almost lost amongst the heroine’s straining for significance), she would seem to have been a strong, independent, wilful, active seeker after the betterment of others. Our heroine, however, thinks only of herself and her precious boredom. The Frenchwoman would no doubt have told her to get off her arse and do something useful – most of her “problems” would have vanished if she’d had something to do with her time. On top of the tediously dragging direction, the lead actress (Rebecca Pauly) is dismal; she mopes through the film with a perpetual slack-mouthed martyr look.

A bit more interesting, but only slightly more exciting, was Alexander Kluge’s DIE PATRIOTIN (THE PATRIOT), an odd thing about the uses of history. Its central point sounds straightforward and sensible when stated simply: history is the sum of the decisions and actions of all individuals, who base their decisions on the information they possess – so in order to produce the best decisions, everyone should have access to all information (cf. Milton’s Areopagitica). Now, that’s pretty simplistic – for instance, what is valid information? As soon as an historical event becomes transmittable information it has in effect been interpreted, coloured by the consciousnesses through which it has passed. It also implies a capability for the human mind to weigh an infinite number of facts, and to draw “correct” conclusions from them. Etc. But the point of view does offer a place from which to begin some practical changes. Kluge’s chief target is the highly coloured official, approved version of history taught in state schools in Germany, giving the young such a selective view that it leads to a perpetuation of bad decisions, a repetition of past mistakes. His call is for a wider range of points of view, the creation of more open minds. His fear is the increasingly fascist tone of German politics. His problem is that he gives all this an overlong, obtuse presentation, using graphics, old newsreels, documentary footage, staged scenes. The film doesn’t present (or attempt to present) history itself; it’s searching for a new way to approach history – a way which would perhaps deflect Germany’s apparent path back into past error. A worthy sentiment, but handled with a leaden Teutonic humour which makes it something of a grind.

Werner Herzog’s remake of NOSFERATU: PHANTOM DER NACHT was one of the big disappointments of the festival – not too surprisingly, I suppose. It’s often visually stunning, but it’s dramatically weak – a too thin retelling of a too familiar story. These days there’s not much to add to the old Count’s saga, so anyone who wants to re-do it doesn’t have many options for making it interesting. The visually lush romanticism of Badham’s film was quite nice. The imagery of Herzog’s film is less dense; he rests his case on the political allegory – which is as thin as the story itself: people don’t believe in the reality of evil, a blindness which allows the evil to continue and proliferate until it consumes everyone – and even those who do see it sacrifice themselves pointlessly because too many just let it go on. Klaus Kinski’s Dracula is quite interesting – a weak and pitiful creature who longs to be able to love and wishes to die – but it’s not very threatening, so a major source of dramatic tension is absent. And his death is perfunctory and anticlimactic.

I couldn’t see in the film Herzog’s “bridge” between the great German expressionist cinema and the modern German film renaissance – in trying to recapture the spirit and sensibilities of the past, he has produced a mere oddity – neither expressionist nor modern. And working in a language not his own (nor the actors’ own) just adds to the clumsiness (though I don’t think the German language version would have been much better – the main weakness lies in the thinness of the dramatic conception). Yet it is often visually beautiful….

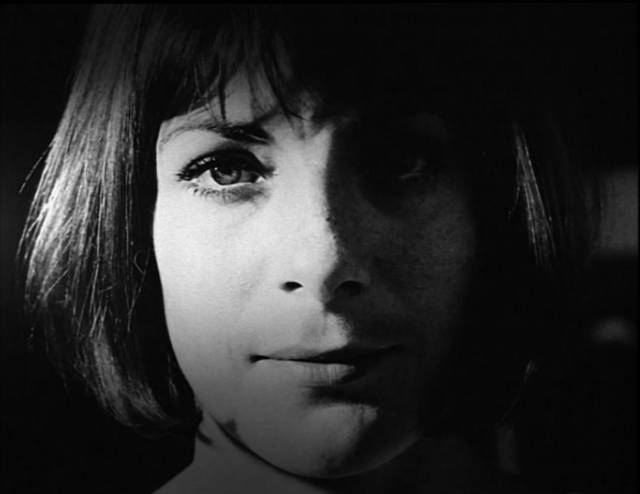

Margarethe von Trotta’s SCHWESTERN, oder DIE BALANCE DES GLÜCKS (SISTERS, or THE SCALES OF HAPPINESS) is a fine psychological drama, tautly directed (by the wife of Volker Schlöndorff), well produced, and superbly acted – particularly by Jutta Lampe. Maria (Lampe) has totally subjugated herself to a successful career. She now lives vicariously through her younger sister Anna, whom she is supporting through medical school. Close since childhood, their personalities are now locked together – and Anna is stifling under Maria’s unconscious effort to turn Anna into herself. Anna is unable to give up her own self and become the other that her sister wants her to be – yet she’s also unable to reject Maria’s demands. She resolves the difficulty by committing suicide. Badly shaken, Maria decides to take another woman as roommate to ease the loss. And gradually she starts over; trying to turn Miriam into Anna, controlling her life and reshaping her into her own image. But Miriam isn’t trapped by the bond of sisterhood; she realizes what’s happening, rebels, and leaves Maria alone. It’s a film which relies entirely on the characters and the complicated ways in which they interact to create dramatic tension – and it succeeds very well. Its portrait of a kind of psychic vampire who sucks the essence from others to fill the vacuum she’s created in herself is remarkably powerful – the more so perhaps for being sympathetic towards Maria, towards the sadness of a lost life.

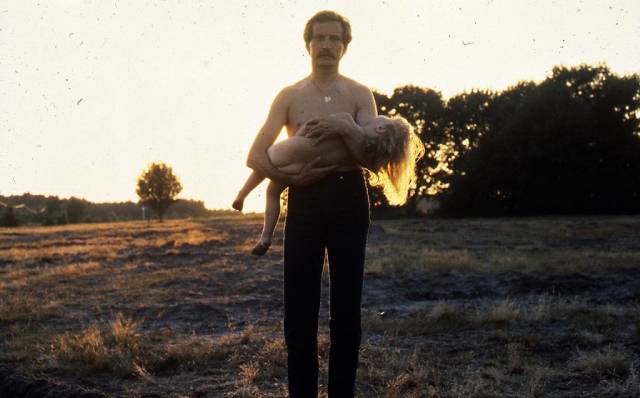

Peter Fleischmann’s DIE HAMBURGER KRANKHEIT (THE HAMBURG DISEASE) is a startling, imaginative hybrid – and one of the most entertaining films at the festival. Satire and horror film, farce and thriller, disaster film – it savagely, and hilariously, tears into the love of order at any cost which is a legendary part of the German mental makeup. A new disease turns up, its victims curling into foetal position and quietly dying. It strikes quickly, without warning. The city is cordoned off, everyone who’s had contact with the infected imprisoned in isolation. A small group break out and flee the city, travelling across a landscape of rapidly increasing disorder. The disaster is an ideal opportunity for the government to strengthen its control. In the name of public safety, anyone can be seized and locked up. The worse things become, the more people desire firm outside control – they turn the “unvaccinated” over to the authorities (a useful way to get rid of an annoying neighbour, or someone whose views you disagree with); these people are carried off to “sanitation camps”. At the same time, it’s all great for business; as the film progresses, a small-time shopkeeper builds up a huge financial empire – starting with personal protection (breathing masks) and working up to huge chemical plants producing “vaccine”. Although no antidote is actually found, PR and propaganda come to convince everyone that the situation is under control – a control which must be diligently maintained by allowing the government a completely free hand. The PR is so good that when the sickness spreads to other countries, German technology – and the police control that goes with it – becomes a major export.

The disease is psychological – a fleeing from the pressures of responsibility in a complex world. The people become sick because they want someone to come along and take the responsibility from them. And the few who can still think are eventually overrun and whisked away.

The film is fast-paced, the cross-country flight exciting and tense, the ending frightening. It’s also full of hilarious images, bizarre moments of hysterical madness (a great chase with a police car after a tank driven by a berserk U.S. soldier), grotesquely comic characters, and some rather vicious jabs – when a woman is caught by the faceless bio-suited plague cops, she’s taken to a camp, stripped, and thrust into a disinfectant shower; the film is loaded with references to Nazi deeds and the part a willing, or at least complacent, public played in them. Reason is willingly abdicated in favour of order (an order which, in fact, is a sham concealing an ever wilder chaos). Everyone just wants to be looked after. It’s an amazing film because it attempts to be so many things – and, remarkably, succeeds in being all of them and balancing them perfectly against each other. As funny as it is, it’s one of the best breakdown-of-society films I’ve ever seen.

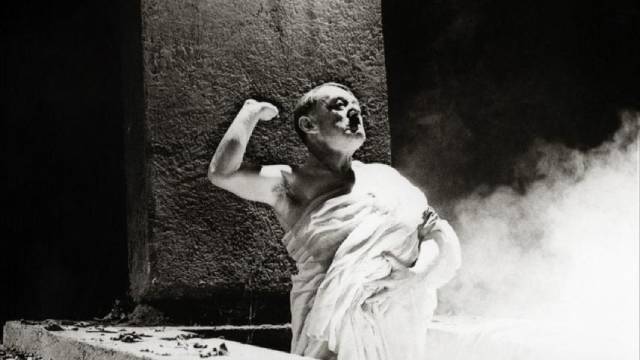

For me, I guess, the event of the festival was Hans-Jurgen Syberberg’s HITLER – A FILM FROM GERMANY (aka OUR HITLER), a massive, overwhelming, seven-hour bombardment of the mind – in four parts, shown together on a single Sunday. A dense lecture with montage, not a film in the traditional sense at all, on the meaning of Hitler, the theme (as Syberberg puts it) of “the Hitler in us”. It was simply too big to absorb in a single session – but even through increasing exhaustion it had a vast amount to offer.

Its starting point is a Christ parallel. The first section, an introduction, a statement of intent, is called The Grail; the film itself is a quest – for the Aryan ideal, for the meaning of the central event of the 20th century: Hitler. Man created god in his own image – and Hitler is the modern god, the repository of 20th century man (materialism, anti-culture, anti-intellectualism….). And he is our justification. Raised high, then destroyed, he is our Christ, taking onto himself our sins. He is our symbol, the great scapegoat for man’s evil. You do something vile – and then point to Hitler: your own evil is diminished and to a degree excused.

The film makes a massive, exhausting attempt to humanize Hitler: a lengthy, appallingly banal – and startlingly funny – droning monologue by his valet, inundating you with minute details of his daily life; another humorous spiel by Hitler’s personal projectionist (he was apparently a great lover of film). There is something disorienting, ultimately frightening about all this because the monster is reduced in scale to an ordinary man, not a creature beyond comprehension – so how do you come to terms with what he was responsible for? This confusion isn’t resolved when Syberberg finally has Hitler speak in the third part. He comes out swinging, the Grand Inquisitor, pointing out with righteous indignation all the evils perpetuated now by the people who self-righteously condemn those same evils in Hitler. The official view of history is reversed; Hitler was just doing the done thing and if he carried it as far as he did it was because so many others were willing to go along with the doing.

The film is hardly cinematic – static visuals, shot in the corner of a soundstage with limited rear projection, lengthy monologues, lectures, actual voices from the period. It’s the sounds – words and music – which matter, the flow of ideas which by their sheer weight flush out our previously fixed ideas and force a reevaluation of what we thought and what we thought we knew. Syberberg supports all this weight with well placed, often relief-giving, touches of humour. But the whole is terribly pessimistic in its view of human nature, the capacity for evil and self-deception – yet it ends with Beethoven’s Ninth and images of a child: hopeful? ironic? Its message for the future is that Hitler has won – the materialist anti-culture has swept away true culture and with it any widespread possibility of thought; commodities are all, and Hitler himself has become one of the biggest.

Comments