Jean Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore (1973): Criterion Blu-ray review

Although I’ve seen the name Jean Eustache over the years, along with the title of his best-known film, The Mother and the Whore (La maman et la putain, 1973), I knew virtually nothing about him or his work. So, sitting down to watch the film on Criterion’s new Blu-ray, I had no expectations … and probably more importantly no context for what I was seeing. My initial response was a mixture of immersion and irritation and, as it unfolded over more than three-and-a-half hours, exhaustion. While on the surface it seems surprisingly simple, there are obviously deeper currents running through it which I was not immediately attuned to. In part, this is due to the social and historical context within which the film was made – an issue at least partly remedied by the disk extras – but more critically the use of dialects and slang carries signifiers which are not apparent to a viewer, like me, who doesn’t speak French and has to rely on subtitles which inevitably can’t convey subtlety and nuance, making the film only partially comprehensible.

This is a huge drawback in understanding the film in which language is so essential. Throughout the lengthy running time, the characters never stop talking. Everything is expressed verbally in a flow of conversations and, more importantly, a series of monologues which simultaneously reveal and conceal the characters to one another, and to themselves, as they try to discover their own place in a world which has lost much of its sense of meaning.

That’s where the context becomes so important: the film was made just a few years after the failed revolution of May 1968, when workers, students, academics, artists and intellectuals joined together to confront the conservative establishment which had become entrenched since the end of World War Two and the Occupation, and had been severely shaken by the Algerian war waged by France against anti-colonial forces in North Africa from 1954 to 1962. During the 1968 uprising, which represented something like a home-grown analogue to that war, there were great hopes across a wide range of French society that a new, more equitable society could be created. But when these efforts were defeated, the sense of failure ran deep.

Although Eustache only glancingly refers to 1968, a contemporary audience would have shared the film’s underlying sense of confusion and despair – it’s telling that the response to the film was divided along generational lines, with younger viewers recognizing their own experience and feelings in the characters’ struggle to define their own identities, while older viewers reacted against its implicit critique of what remained a largely conservative society.

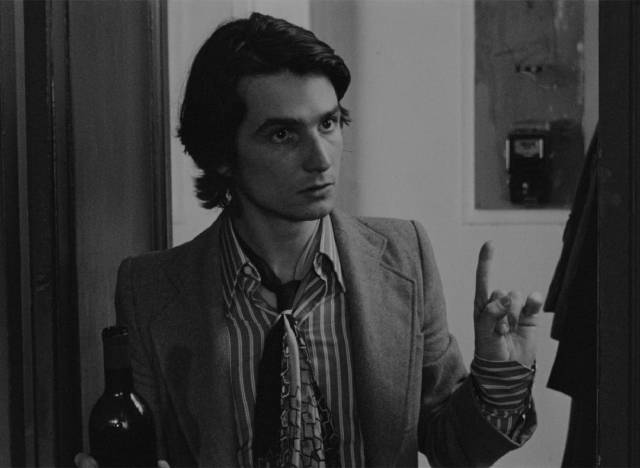

All of this became more clear after watching the extras. What I experienced while actually watching the film was the intimate personal drama of the three main characters. Initially, we are limited to the point of view of Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud), who very quickly became the source of my irritation. Pretentious, narcissistic and stiflingly self-absorbed, he never stops talking – talking at rather than to the people around him, giving the impression that everything he says is a rehearsed attempt to define his identity in a way which might hold off a deep sense of pointlessness.

We first see him waking beside a woman and quietly slipping out of the apartment. Borrowing a car from a neighbour, he drives to the Sorbonne where he stops another woman on the street. Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten) is about to begin a new semester at the university, but he persuades her to hear what he has to say. In a nearby park he talks about their relationship, which she considers to be over, and pleads with her to marry him – the idea of marriage and a child seem vitally important – but while she won’t give him a definitive no (she’s living with another man, just as he’s living with another woman), she’s obviously not interested.

Alexandre’s aimlessness here is given a cloak of literary romanticism (early in the film we see him reading a volume of Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu), which leaves the viewer as unconvinced as the woman he supposedly wants to marry. He reveals his complete self-absorption by insisting that if she won’t marry him, she must marry the man she’s living with so that he can stop thinking there’s any hope for them. Eventually, to assert his own power, he gets angry and walks away from her.

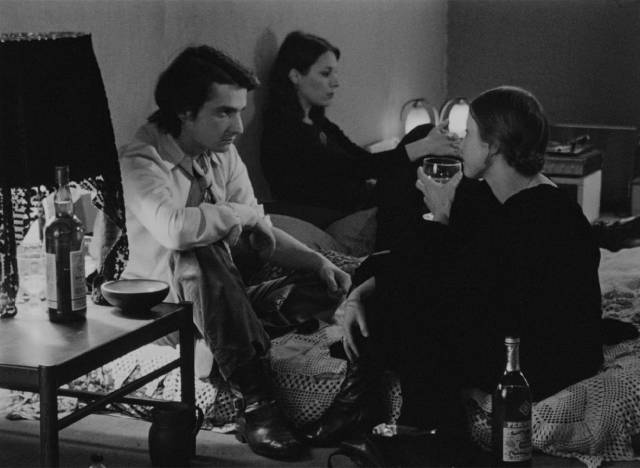

Despite living with Marie (Bernadette Lafont), a slightly older woman who has a dress shop and apparently supports his idle lifestyle, he continually pursues other women, behaviour which exasperates Marie, though she mostly tolerates it because of her feelings for him. Idling in a cafe, he sees another woman and follows her, asking for her phone number. This is Veronika (Françoise Lebrun), a Polish nurse who lives in a small room at the hospital where she works. Alexandre embarks on an affair with her and the film focuses on the increasingly complicated emotional currents which permeate his relationships with the two women.

Veronika is working class, in contrast to the petit bourgeois Alexandre and Marie. She’s also promiscuous, spending her time outside of work going to clubs, drinking and dancing, and engaging in casual sex. She begins calling late at night, drunkenly waking Marie and Alexandre. While Marie is initially quite tolerant of the affair, when she invites an old male friend to dinner one evening, Alexandre explodes in a jealous rage and storms out – yet another reason to find him irritating, an unexamined, chauvinistic double standard. And yet eventually Veronika’s intrusions lead to an awkward ménage à trois, with the two women forming a tentative bond which becomes threatening to Alexandre. But this doesn’t last, ending with a fed up Marie attempting suicide and finally being left in melancholy solitude as Alexandre pursues Veronika to an inconclusive final scene where once again he proposes marriage. Although Veronika seems to agree, both characters remain detached and isolated, their confusion about their own identities and sense of purpose making the decision to marry as meaningless as everything else in their lives.

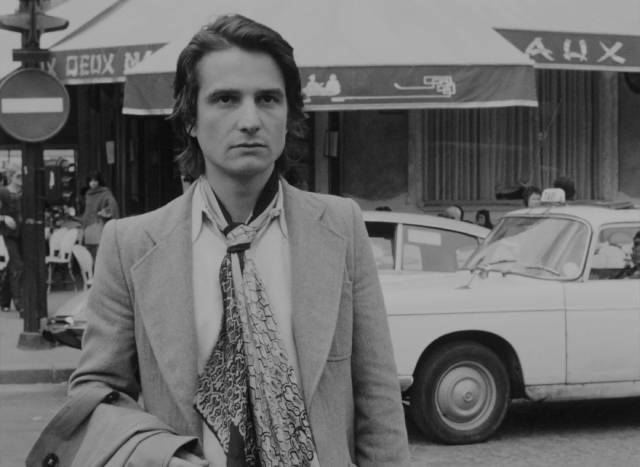

While the “narrative” seems slight and in some ways conventional, the film’s execution is something else, generating a mysterious dramatic and emotional power. Even at 219 minutes, it remains compelling. This is partly due to Pierre Lhomme’s superb documentary-like cinematography which evokes early-’70s Paris vividly, the streets, cafes and apartments providing a viscerally detailed ground against which the lives of these unanchored characters play out.

More important is Eustache’s script, which apparently consists largely of actual conversations drawn from his own relationships, and artfully gives the impression of a kind of shapeless naturalism while actually providing a rigorous structure which makes every moment count. But most important are the performances. Léaud brings to Alexandre the full weight of his history as perhaps the singular face of the New Wave; it’s his presence which gives The Mother and the Whore the air of a summing up, an exhausted conclusion to the promise of all those rebellious, iconoclastic movies which helped to define the social currents which led to May 1968, a promise which crashed in defeat and left all the rebels of Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Louis Malle and others adrift and alienated.

Initially, the film is closely tied to Alexandre and his endless attempts to create a sense of place and meaning through ceaseless talking. But gradually this focus shifts to the two women. Alexandre’s intellectual pretension is a cover for his emotional immaturity and, despite the sexual nature of their relationship, Marie obviously fills the role of the title’s “mother”, a stabilizing, supportive woman who indulgently underwrites his idleness with a mixture of exasperation and amusement. Veronika, on the other hand, despite her position as the “whore”, is an innocent, her sexual promiscuity an endless search for connection (as a Polish woman living in Paris, she is by definition alienated). The emotional and dramatic climax of the film is her long, fraught monologue about being perceived unjustly as a whore because conservative convention perceives a woman’s openly expressed sexuality as immoral (and in a Catholic society, sinful). In comparison with Alexandre’s self-generated angst, the emotional pain of the two women has an authenticity, which in itself poses a criticism of the post-’60s climate in which the pretentiously intellectual man is still validated by cultural tradition while women are devalued by that same tradition.

While the film is bleak, its view of the post-’68 malaise almost nihilistic, this is offset by the craft with which it has been made. Despite the length, its pace and dramatic rhythm maintains viewer engagement so that it seems to pass almost effortlessly. Lhomme’s camerawork is precise and unadorned, always focused on the characters – often centred and looking into the lens to connect with the audience – so that we experience their thoughts and emotions with an immediacy and clarity which allows us to penetrate the layers of self-deception with which they try to maintain some form of control over their lives. Eustache establishes and sustains a fascinating dramatic tension between the vertiginous psychological state of these characters and the confident artistic control he maintains over the material. The Mother and the Whore is something like a summation and epitaph for the New Wave and its dream of cultural transformation.

*

The disk

The disk has been mastered from a new 4K transfer from the original 16mm reversal A&B rolls and it looks absolutely gorgeous. Contrast and detail are excellent, with a pleasing grain texture and no visible signs of damage. The sound, mastered from an optical print, is clear and unadorned – apart from dialogue and the ambience of Paris streets and cafes, the only music comes from the record player in Marie’s apartment.

The supplements

There are five disk extras, totalling about seventy-five minutes, starting with a newly filmed conversation between filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin and author Rachel Kushner (32:39), which ranges from the New Wave to May 1968, the confluence of politics and cinema, the impact of Eustache’s film on Gorin at the time and its effect on Kushner decades later.

An interview from 2022 with Françoise Lebrun (14:16) covers her background and personal relationship with Eustache and the effect working on the film, her first, had on her life.

A clip from French television (10:30) reports on the film’s debut at Cannes in 1973 (where it received a mixed reception, but won the Grand Jury Prize), including interviews with Eustache, Lebrun, Léaud and Lafont.

A featurette (16:52) goes into detail about the difficulty involved in restoring the existing elements to create this pristine new master. The technology and tools now available can perform miracles.

There’s also a re-release trailer (2:20) and a booklet with a director’s statement written by Eustache at the time of the film’s release and an essay by writer Lucy Sante.

Comments