Year End 2024

Hard to believe another year has gone by and once again I feel some kind of obligation to offer a summary of the year’s viewing. This time, I’ll actually limit myself to ten disks (well, eleven, but that’s close enough). These aren’t necessarily the best or most important releases (and some of them were released before 2024, though they’re new to me), but they’re ones which sparked my interest in ways which made them stand out. (I would have included a number I watched in December, but intend to write something about them in the New Year.)

*

Another Body (Sophie Compton & Reuben Hamlyn, 2023)

This documentary about a college student who discovers she’s the victim of deep-fake Internet porn and sets out to uncover the identity of the scumbag who has targeted her uses the same deep-fake video technology to conceal her identity while allowing her to express the full range of her emotional reactions to a devastating situation and the journey she undertakes to restore her sense of agency. It certainly helps that she’s a strong, engaging character around whom the filmmakers construct a gripping detective story. Utopia Blu-ray with commentary, interviews and several festival screening Q&As.

Charlie Victor Romeo (Robert Berger, Patrick Daniels & Karlyn Michelson, 2013)

Another innovative use of documentary to illuminate some disturbing technological sources of vulnerability. In this case, the director/performers re-enact a series of actual plane crashes using a spartan set representing various cockpits and nothing more than transcripts from the planes’ voice recorders. The tension between the flight crews’ cool, matter-of-fact professionalism and the catastrophic technical failures which lead to fatal crashes make it all too clear how vulnerable we are to the machinery we surround ourselves with and trust our lives to. Dekanalog two-disk Blu-ray with both 3D and 2D presentations, commentary, a lengthy presentation about one of the crashes, a couple of scenes recorded at performances of the original stage version, and some television news reports.

Closed Circuit (Giuliano Montaldo, 1978)

This self-referential mystery captures some of the essence of the movie-going experience by transforming the audience’s immersion in the story unfolding on a theatre screen into something dangerously all-consuming. During a matinee screening of a spaghetti western, a member of the audience is killed by a gunshot during the climactic shoot-out; the police seal off the theatre and interrogate both customers and staff, while trying to figure out where the shot came from. When they re-enact the incident, running the film again, the volunteer sitting in the victim’s seat is also shot at the same moment. It becomes clear that the gunman up on screen is targeting those watching. Montaldo’s approach is both playful and rigorous as what begins as a police procedural evolves into a metaphysical mystery about the strange ways our imaginations interact with the movies we watch. Severin Blu-ray with an illuminating introduction from disk producer Kier-La Janisse, an interview with Montaldo recorded shortly before his death, and an appreciation of actor Flavio Bucci by Kat Ellinger.

A Fugitive From the Past (Tomu Uchida, 1965)

Tomu Uchida addresses the social and economic chaos facing Japan after defeat with a long, complex drama which threads surreal elements through an otherwise realistic story of crime, guilt and a tragic misunderstanding, all framed within a ten-year police investigation. The Arrow Blu-ray has an introduction from Jasper Sharp and scene-specific commentaries from several experts on Japanese cinema.

The Great Silence (Sergio Corbucci, 1968)

Sergio Corbucci was one of the masters of the Italian western and The Great Silence (1968) is his masterpiece in the genre. Made two years after his influential Django (1966), which took the genre in a darker direction than the films of Sergio Leone, it’s one of the bleakest – replacing parched southwestern deserts with snowbound mountains and bandit gangs with rapacious capitalists, it prefigures Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971) with an even harsher view of Manifest Destiny; instead of the small-time businessman being swept away by corporate interests, it centres on the ordinary people who are victimized by those interests and don’t stand a chance against greed devoid of empathy. The excellent Masters of Cinema transfer is supplemented with three commentaries and several documentaries and featurettes about Corbucci, the production and the genre, as well as a pair of alternate endings.

The Iron Prefect (Pasquale Squitieri, 1977)

The intermingling of organized crime and right-wing politics in Twentieth Century Italian history is illuminated by the story of a police official sent to Sicily in the 1920s by Mussolini. Cesare Mori used extra-judicial methods to smash the Mafia’s hold on the island, only to run afoul of the organization’s connections with powerful political figures. Squitieri draws on the western and the war film in depicting the actions of the crusading official whose methods reflect the corruption he’s fighting. Relative newcomer Radiance gives the film a superb presentation with a number of useful supplements which provide insight into the history behind the story.

The Kingdom 1-3 (Lars von Trier, 1994-2022)

I hadn’t watched Lars von Trier’s The Kingdom (first and second series) in years, but the release of a Blu-ray set which included the originals along with the new Kingdom: Exodus (2022) provided a good reason. I saw the first four episodes at the Cinematheque back in the ’90s, and the second four when they were released in a Danish DVD set which included both series. The mix of soap opera, satire and ghost story was enormously entertaining, balancing comedy and horror with great skill. But the story remained open-ended for a quarter century, until von Trier finally completed the trilogy with five new episodes in 2022. Though the stylistic freshness had inevitably diminished, and a number of key cast members had died, the new series nonetheless expanded on the narrative and carried it to a dark, apocalyptic conclusion. Although the two original series were deliberately ragged and grainy, Mubi have done a good job with their new digital upgrade and the seven-disk set carries over some of the original DVD extras, though unfortunately there are no new supplements about the third series.

Phase IV (Saul Bass, 1974)

I actually revisited Phase IV (1974), the sole feature directed by Saul Bass, twice this year – first in 101 Films’ two-disk special edition (which included a second disk of Bass’s short films and documentaries), then in Vinegar Syndrome’s dual-format 4K upgrade. Both editions are excellent, though the VS further improves the picture quality. Although 101’s inclusion of the short films makes their set a keeper, VS one-ups them by including a reconstructed preview cut which incorporates Bass’s original abstract ending (only an extra on the 101 disk) with two soundtrack options – the U.S. version includes explanatory narration which is absent from the British preview cut and the theatrical version. Whatever its limitations as drama, the film offers some remarkable imagery and a cosmic sense of awe which echoes 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) more than the pulp sci-fi action movies which became dominant a few years later with Star Wars (1977). Both editions include commentaries and multiple extras.

Reptilicus (Sidney W. Pink & Poul Bang, 1961)

I never would have expected to be including Sidney W. Pink and Poul Bang’s generally reviled Reptilicus (1961) in a year’s best list, but Vinegar Syndrome’s lavish three-disk dual-format edition reveals much to appreciate and enjoy in this rather silly giant-monster-on-the-loose movie. Yes, the effects are often risible, but they also have an undeniable charm, while the location shooting in Denmark and some of the action set-pieces are quite impressive. The restorations of both the Danish and American cuts are excellent and there a number of extras in which experts express their affection for the movie.

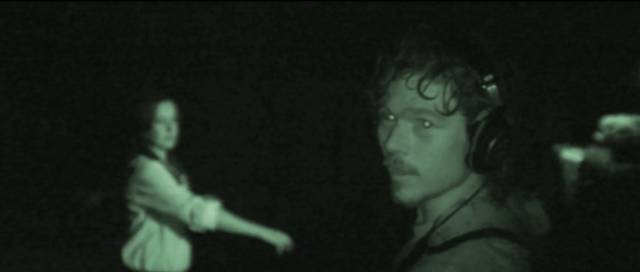

The Tunnel (Carlo Ledesma, 2011)

I remain a sucker for found-footage horror and Carlo Ledesma’s The Tunnel (2011) is one of the best I’ve seen in a while, benefiting from an impressive location (ominous tunnels beneath the city of Sydney in Australia) and a well-thought-out rational for the characters recording their own escalating fear and gruesome ends – a television crew sneaks into the forbidden tunnels looking for answers to the recent disappearances of a number of homeless people. If the story is somewhat derivative (Raw Meat, The Descent, C.H.U.D.), the execution is impeccable. Umbrella’s disk provides some fascinating context about the project’s unconventional production and distribution.

Victims of Sin (Emilio Fernández, 1951)

Emilio Fernández was a familiar face in westerns, most notably as Mapache in Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969), but he was also a prolific writer and director in Mexican cinema with a career spanning almost forty years. That work has been far less visible to English-speaking audiences, but if Criterion’s restoration of his 1951 feature Victimas del pecado (Victims of Sin) is anything to go by, there’s a large body of work waiting there to be explored. This melodrama takes the point of view of a woman struggling to assert herself in a brutally exploitative patriarchal society – a cabaret performer who takes responsibility for an abandoned child and slides into prostitution in order to survive. The noir visual style edges into social horror, with suffering and violence assuming an almost surreal intensity before resolving into a tentatively redemptive ending. An excellent restoration with several supplements dealing with its place in Mexican cinema.

*

There were many more interesting and valuable releases in 2024, but I’ll stop here.

*

Reading

I should also mention a few books I read this year – probably too few as I read less as I watch more. A good chunk of my reading time has gone to books and booklets included in disk releases, but of the actual books, I’ve enjoyed several film-related titles.

Mr. Murder: The Life and Times of Tod Slaughter (Hemlock Books, 2019) by Denis Meikle, Kip Xool and Doug Young proved an excellent, informative and entertaining companion to Indicator’s Tod Slaughter box set. Its detailed account of the actor’s life increased my appreciation of the movies immeasurably.

Film Business (Film Desk Books, 2023) is a collection of New Yorker pieces by Lillian Ross, one of the best observers of the U.S. movie industry for more than six decades. Her book about the making of John Huston’s Red Badge of Courage (1951) was one of the first, and still one of the best, nuts-and-bolts accounts of a production, especially insightful on the conflicts between art and business. The almost two-dozen essays here, spanning from a piece about Red Scare paranoia in Hollywood (1948) to a brief account of a party celebrating the 20th anniversary re-release of Brian De Palma’s Scarface in 2003, provide sharp portraits of individuals from Otto Preminger to Jean-Luc Godard, and lengthy accounts of individual filmmakers’ struggles – including Preminger’s legal case to prevent his Anatomy of a Murder (1959) being cut up for commercial breaks on network television and Francis Ford Coppola’s attempt to run a studio and use innovative video technology in the production of One from the Heart (1981). In addition to her skills as a reporter, Ross was a witty and stylish writer whose prose is a pleasure to read no matter what her subject.

Robert M. Rubin’s Vanishing Point Forever (Film Desk Books, 2024) may seem a bit excessive – an expensive, elaborately designed 572-page paean to a fifty-plus year old movie which received almost no critical respect when originally released – but for fans of Richard C. Sarafian’s Vanishing Point (1971), it’s a real treat. Packed not only with production information and images, it also revels in muscle car culture with articles and advertising focused largely on the Dodge Challenger which is the movie’s real star. Made at the height of the road movie craze, this story of an enigmatic man who lives only to move and becomes a target for the cops of multiple states is the apotheosis of the American dream of not being tied down, of absolute independence and freedom – an illusory dream which can only end in death, as it does in so many movies, from Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) to John Hough’s Dirty Mary Crazy Larry (1974) to Ridley Scott’s Thelma & Louise (1991). Vanishing Point strips the narrative to minimalist perfection and ramps it up with some of the most exhilarating car stunts ever put on film. Along with some essays and reviews, Rubin includes the complete final draft of Cuban author Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s script; Infante himself complained that Sarafian had cut out much of what he had been trying to say about American culture’s relationship with the western landscape, but the film (beautifully shot by John A. Alonzo) conveys much of what was written on the page in purely visual (and emotional) terms. After reading the book, I re-watched the film for the first time in years and it holds up now perhaps better than any of its contemporaries, seeming less dated than many because it leans less heavily on the ’60s counterculture.

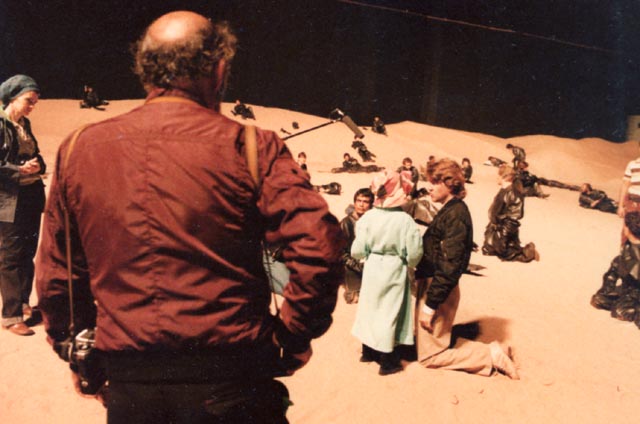

After reading Max Evry’s hefty A Masterpiece in Dissarray, I couldn’t resist picking up a couple of other books about David Lynch’s Dune (1984) – and yes, the fact that they mentioned me was part of the appeal. Christian McCrea’s Constellations: Dune (Auteur, 2019) is an academic treatise on the novel, the previous attempts at adaptation, and the troubled production and release of Lynch’s film. As any such account inevitably will, McCrea’s short book acknowledges the film’s flaws, but also appreciates what makes it almost unique in the genre – that is, its richly imaginative design and the personal obsessions Lynch brought to the material.

Kara Kennedy’s Adaptations of Dune (Blue Key, 2024) is just what it says, an analysis of the various adaptations of Frank Herbert’s books, beginning with the abortive earlier attempts, then devoting lengthy chapters to Lynch’s film, John Harrison’s Sci-Fi Channel mini-series (2000), and ending with Denis Villeneuve’s part one (2021) – the book was written before the release of part two. It’s a bit of a dry read, breaking its examination of the process of adaptation into a series of discrete sections on narrative, characters and design. Initially, Kennedy seems very critical of Lynch’s version, but in retrospect it fares quite well in comparison to the other two adaptations – but all three fall short when compared to the detail and complexity of the book(s).

I keep telling myself that I’m finally done with Dune, but something always draws me back. I guess you’re never quite finished with the truly formative experiences in life – and for me, working on Dune was certainly that!

Comments