More folk horror, old and new

Although not by design, since watching Severin’s All the Haunts Be Ours Volume 2 I’ve seen several other folk horror movies recently released by the BFI and 101 Films. While Severin casts a wide net, broadening the idea of what constitutes folk horror, these other releases are closer to the original attempts to define a genre which was rooted in a very British context – after all, those original attempts derived from the “unholy trinity” of Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General (1968), Piers Haggard’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) and Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973). While more recent productions have self-consciously been shaped by the idea of folk horror as a specific genre, those earlier films were individual works which drew on history and themes of religious conflict without a deliberate attempt to fit into pre-existing parameters.

This is analogous to the origins and development of film noir, which grew to a large degree out of the social and psychological disruptions of the Second World War, codified in a very distinctive visual style and the emergence of a number of character archetypes. In time, removed from the original social context, neo-noir became a genre which drew self-consciously on that visual style and those character types. Similarly, those original folk horror movies were also rooted in a particular social context – specifically, the disruptions of the mid-to-late-’60s which represented a radical generational break between a conservative post-war order and a desire for a less repressive society, socially, politically and sexually. One element of this effort drew on the burgeoning interest in pre-Christian paganism which had arisen since at least the ’20s, spurred by the work of Margaret Murray and Gerald Gardener which explicitly attempted to redeem adherents to an ancient religion from the negative reputation they’d been burdened with by their oppressors. The particular expressions of this conflict differed notably in each of the three key movies – set during the English Civil War, Witchfinder General dealt with a corrupt establishment so deeply ingrained that it destroys everyone who opposes it; The Blood on Satan’s Claw is actually something like a reactionary riposte in which the rebellious young threaten the social order and must be reined in by an authority figure who represents the kind of establishment condemned by Witchfinder General; The Wicker Man presents a more balanced view of that conflict, with an uptight authority figure steeped in Christian orthodoxy confronting the survival of pre-Christian paganism, with both sides seen as fanatically destructive.

With The Wicker Man, one of the central tenets of English folk horror was firmly established. This is the idea that the land itself embodies layers of history, with the past surviving as a living force. Pre-Christian animism exerts a power over those who now occupy the land, making their apparent ownership and dominance tenuous at best. This concept of a living landscape precedes modern folk horror, present in Gothic literature (the moors of Wuthering Heights, the Wessex of Thomas Hardy, the landscapes of Ann Radcliffe, the ghost stories of M.R. James, E.F. Benson, Algernon Blackwood and Arthur Machen). Its influence can even be seen in the films of Michael Powell, where the emphasis is mystical rather than horrific, particularly The Edge of the World (1937), A Canturbury Tale (1944), I Know Where I’m Going (1945) and Gone to Earth (1950).

In post-Wicker Man folk horror, the survival of pre-Christian religion is a central theme, whether the nature-worship of the Druids or something even more ancient, with hints of H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic horror. In each of the three films I’ve just watched, these forces surface to undermine the complacency of characters who have largely become detached from the spiritual roots of the land, in each case with devastating consequences.

Starve Acre (Daniel Kokotajlo, 2023)

Daniel Kokotajlo’s Starve Acre (2023), based on a novel by Andrew Michael Hurley, is exemplary of modern self-conscious folk horror. Set in the ’70s, it has a couple with a young son move from the city to a remote farm in Yorkshire, where it seems to be perpetually raining. The wife Juliette (Morfydd Clark) has an undefined role, poised on the edge of women’s place in society being transformed by a more aggressive feminist movement. She seems adrift in the old house, with no purpose beyond watching over (and worrying about) five-year-old Owen (Arthur Shaw), who has asthma and is beginning to show troubling signs of increasing anti-social behaviour. He seems to be hearing a voice in his head, getting into fights at school, and finally committing an appalling act of violence at a local fair, where he blinds a pony with a stick (a cultural reference point, Peter Shaffer’s play Equus having debuted in 1973).

Despite these obvious signs that something is wrong, his father Richard (Matt Smith) resents Juliette’s concern and insistence that their son be taken to a doctor for evaluation. This turns out to stem from his own troubled past with an abusive father, who had owned the farm; he’s determined to love Owen unconditionally and protect him – which translates into a form of denial and a refusal to acknowledge that anything is wrong. As a rift begins to form between the parents, Richard undertakes an archaeological dig on the property. Legend has it that there was once a great oak which was not only a spiritual meeting place, but also a place of punishment, with those condemned by the community being hanged from the branches. The tree was cut down long ago, but he believes its roots still lie beneath the field.

As he digs, he also discovers a book kept by his own father, in which the local legend is fleshed out, and which brings to the surface memories of abuse – as a child, Richard had been offered by his father as a sacrifice to the ancient god(s) of the land, embodied in the mythical figure of Jack Grey, who seems to be the source of the voice in Owen’s head. Things take a dark turn when Owen dies suddenly from an asthma attack and Richard uncovers the buried skeleton of a great hare, laid between the roots of the ancient tree. Reassembling the bones in his study, he finds the flesh beginning to re-grow. An old friend of his father’s named Gordon (Sean Gilder) explains that for Jack Grey to be resurrected, a three-part sacrifice is required – a child, a man and a woman. Richard’s father failed because the sacrificial child must be loved and his father had no love for Richard; Owen on the other hand…

As the great hare (long a symbol in pagan tradition) revives, events follow a grim, inevitable course with Richard and Juliette drawn into the ancient tradition and performing the necessary violent rituals to restore Jack Grey, essentially wiping away modernity and reestablishing the primacy of a harsh natural order whose roots are firmly planted in pre-history.

With its unsettling mood and evocative depictions of an inhospitable landscape (shot in widescreen by Adam Scarth), Starve Acre risks coming across as an academic treatise on the genre, but as chilly as it is it nonetheless draws the viewer in with excellent performances from Clark, Smith, Gilder, Shaw and Erin Richards as Juliette’s sister Harrie, who comes to stay, bringing the self-assurance of modernity into a household descending into mystical darkness.

The BFI dual-format edition naturally has an excellent transfer, with a filmmaker commentary, interviews with Smith and Clark and the team responsible for the impressive animatronics which bring the great hare to life, plus an interview with author Hurley, a short deleted scene and a brief behind-the-scenes featurette.

*

The Outcasts (Robert Wynne-Simmons, 1982)

Robert Wynne-Simmons has an honoured place in British folk horror as the scriptwriter of The Blood on Satan’s Claw, and yet his sole feature as a director has remained little known until now, with an excellent Blu-ray release from BFI Flipside. Made a decade after Satan’s Claw, The Outcasts (1982) is a more subtle film, eschewing the earlier movie’s nudity and more explicit violence in favour of atmosphere and ambiguity. In its depiction of a harsh community where Christianity has only a tenuous hold and of a girl on the brink of womanhood who is becoming aware of a potent inner power, it seems very much like a precursor to Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015); and with its ambiguous treatment of her power – is it a delusion given force by the superstitious beliefs of the people around her or a genuine manifestation of the supernatural? – it bears some resemblance to Nigel Kneale’s television play Murrain (dir. John Cooper, 1975).

Set in a small Irish community just before the onset of the Great Famine in the mid-19th Century, the film centres on Maura O’Donnell (Mary Ryan), one of the daughters of a violent farmer (Don Foley). There’s something a little strange about Maura, which makes her a target of other children who bully her for being different. While inappropriate to impose a modern interpretation on that difference, we might suggest that she’s “on the spectrum”; she gives the impression that she’s on the border between this reality and an unseen other world, a world of myths and superstitions over which the Church asserts a tenuous authority.

As villagers gather at the O’Donnell farm to celebrate the marriage of sister Janey (Bairbre Ní Chaoimh) to Eamon Farrell (Máirtín Jaimsie), lingering traces of an older order appear in the form of a trio of musicians concealed under straw masks. While they’re invited in, however, Maura is uneasy because there’s a local legend about another fiddler called Scarf Michael, a sinister figure from the spiritual realm whose music supposedly presages death. Led by some of the celebrants into the woods, Maura is abandoned; a shadowy figure appears and she finds herself in the company of Scarf Michael (Mick Lally), who senses in her a kindred otherworldly spirit.

Revealing the strange power of his music, he draws her deeper into the mystical realm while bad things begin to happen in the community – as the Great Famine begins crops fail, animals die – and blame falls on Maura, who is deemed a witch. Grabbed by an angry mob, she’s carried to the sea shore where they intend to drown her. While everything up to this point could be explained naturalistically, the final act of the film slips into the supernatural; the mob’s actions are interrupted by the appearance of Scarf Michael and Maura vanishes. She has crossed over, wandering with Scarf Michael as her own powers grow in strength. But the price she pays is steep; there’s no way to return to the material world and go back to her family … she’s become a spirit creature like Scarf Michael himself, haunting the countryside.

Like Starve Acre, The Outcasts is set in a dark, dank landscape oppressed by bad weather; this ground is inhospitable, its occupants clinging to life and fearful that it can’t sustain them. The land is ancient and whatever forces animate it, they have no interest in nurturing those who cling to it. Beautifully shot by Seamus Corcoran, whose sole cinematography credit this is, though he had a lengthy career as a camera operator on major movies, the film has a powerful sense of gritty period realism, aided by excellent performances from a largely unfamiliar cast – the most recognizable face is Cyril Cusack as local fixer Myles Keenan, who negotiates disputes between families, including arranging the marriage of Janey and Eamon which is opposed by her father.

The restoration by the Irish Film Archive is supplemented with a commentary by a folklore expert, a brief interview with Wynne-Simmons and a featurette in which he comments on a gallery of behind-the-scenes images, plus a half-hour experimental short called The Fugitive which he made in 1964.

*

The Stone Tape (Peter Sasdy, 1972)

Although Starve Acre and The Outcasts were new to me, I’d seen The Stone Tape (1972) several times before, thanks to the BFI’s 2001 DVD release. Given the film’s origins as a taped BBC drama and the limitations of early DVD technology, allowances definitely had to be made for a mediocre image. One of the most surprising things about the new 101 Films Blu-ray is just how much they’ve been able to clean up and polish the original standard definition source; colours are vibrant, contrast generally fine, and while it obviously still has the look of a television production from the early ’70s, it’s a huge improvement over the DVD and makes an excellent companion for 101 Films’ edition of the BBC’s Ghostwatch (1992) – both shows represent a modern take on British television’s tradition of period ghost stories.

Directed by Peter Sasdy, a prolific television director who branched out into features for companies like Hammer and Tigon in the ’70s, The Stone Tape was written by Nigel Kneale, who once again blended science fiction with the supernatural to create a potent narrative about the limits of knowledge and the unsettling effect of historical forces to which modern rational attitudes have made us blind. Thematically, the film is something like an extension of Quatermass and the Pit (BBC 1958-59; Hammer 1967), though here the influence of ancient Martians is replaced with a powerful entity which permeates the English landscape going back far into prehistory.

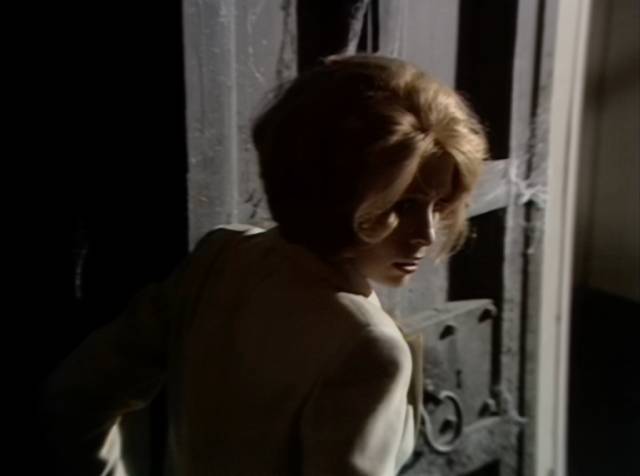

This is the animating force perceived and worshipped by ancient tribes, to whom placatory sacrifices were made since it apparently had (has) little concern for the human inhabitants of the land. But before the climactic revelation of this entity, Kneale presents a scientific explanation for ghosts and hauntings. Funded by an industrialist looking for the next big thing, researcher Peter Brock (Michael Bryant) moves his team and a lot of up-to-the-minute technology into a large country estate which has been left empty since it was used by the military during the War. What he’s seeking is a new, more stable and long-lasting recording medium for data storage. Along with various scientists and technicians, the team includes computer expert Jill Greeley (Jane Asher); although her analytical skills are crucial to the project, she faces casual sexism which constantly undermines her insights – not least from Brock himself, who is also involved with her sexually despite being married.

As with any old country house, the estate has a reputation among locals for being haunted and one room in particular, in which the project’s computer memory equipment is supposed to be installed, gives everyone the creeps. Odd noises, sudden cold … and eventually the apparition of a woman falling to her death from a stone staircase. Not everyone can see her, or hear her scream, but Brock decides to divert resources to investigate the haunting. As in Quatermass and the Pit, this effort uncovers a history of odd phenomena, including the death of a maid early in the century and a couple of attempts at an exorcism going back a hundred years or more.

Because nothing is showing up on the equipment and perceptions vary widely among members of the team, Brock loses interest. But Jill, as the one most deeply affected, can’t let it go and she invests computer time to analyze the unreliable data she’s collecting, despite being told not to. It’s her persistence which finally achieves a kind of breakthrough, which Brock immediately overreacts to – she seems to have solved the problem of ghosts by discovering that they are apparently recordings of intense, emotionally charged moments imprinted on the stones of the place where those events occurred. Could this be the medium Brock has been looking for?

He initiates experiments intended to access these “recordings” by battering the room with various intense sound frequencies, while Jill wonders whether the “recording” is more than a mere visual and aural imprint; is the maid actually aware and re-experiencing the moment of horror as something terrifies her and she falls to her death? If the apparition is conscious, then Brock’s attempts to replay the moment over and over again are extremely cruel. But once again, results are unclear and when it appears that the experiments may have erased the record of the woman’s death, Brock abandons the line of enquiry as a dead end.

Jill, on the other hand, continues to use her computer to analyze the data, coming to the conclusion that the haunting was merely the most recent surface layer of recording; and that Brock’s attempts to unlock the “memories” encoded in the stones have stirred up much deeper and older traces. On re-entering the room and climbing the stairs, she finds herself emerging into an ancient place inhabited by a monstrous, inhuman entity … the very thing which had terrified the maid and which causes Jill herself to fall to her death. Her ability to access the stone’s “recording” makes her just the most recent sacrifice to the ancient “god”, with the film culminating in a glimpse of Lovecraftian cosmic horror.

While The Stone Tape bears thematic similarities to Starve Acre and other stories about characters encountering the primal forces which animate the landscape, running beneath the everyday experience of people who remain largely unaware of the horrors which are so close but generally remain invisible, it displays Kneale’s typical use of a rational, scientifically plausible explanation for aspects of the supernatural. What distinguishes his work from typical attempts to explain away the supernatural is that he manages to up the ante; his explanations deepen the horror rather than dissipating it, and The Stone Tape is one of his finest stories. (There’s a more prosaic strain of horror running through the film – which may be more apparent now than when it was made – in the abrasive sexual politics of the team; in general, the project is in the hands of a rowdy boys’ club of technicians, but more specifically Brock is emotionally and psychologically toxic in his treatment of Jill, his arrogance ironically making him blind to the remarkable discovery she has made about the nature of reality.)

In addition to the impressive restoration, the Blu-ray includes the Kneale commentary from the BFI DVD along with a new commentary, plus a 42-minute retrospective documentary examining the film’s lasting legacy and a featurette about Kneale with his biographer Andy Murray. The limited edition comes packaged in a rigid slipcase with a booklet containing a pair of essays, a set of postcards and a reproduction of the 165-page script.

Comments