Notes on Recent Viewing, part two

Captain Phillips (Paul Greengrass, 2013)

After a decade of working in television on documentaries and drama, and following two minor theatrical features, Paul Greengrass made a real impression with Bloody Sunday (2002), a gritty, gripping account of an atrocity committed by British forces in Northern Ireland in 1972 (which was the main impetus for the IRA bombing campaign in England throughout the mid-’70s). The power he displayed in that film has been somewhat dissipated since in a string of American thrillers which too often succumb to his excessive use of shaky-cam and hyper-active editing, the worst offenders being his two Bourne sequels starring Matt Damon (The Bourne Supremacy and The Bourne Ultimatum). Greengrass seems to be more restrained when he gets closer to “reality”, whether in the docu-drama United 93 or his political thriller about the early stages of the Iraq occupation, Green Zone. But even these more “realistic” films adhere to a Hollywood formula which dictates that the narrative build towards an explosive action climax. His latest film, Captain Phillips, starring Tom Hanks, and based on the actual story of an American freighter captured by Somali pirates, shows both the strengths and weaknesses of Greengrass’ technique.

In 2009 the American freighter Maersk Alabama was making its way down the east coast of Africa when it was attacked by a small group of Somalis in a skiff. The ship only had fire hoses for defence despite its route being through known dangerous waters; with no weapons of their own, most of the crew took refuge in the engine room, while Captain Richard Phillips and some of the officers remained on the bridge where they were held at gunpoint. Having got off a distress call, Phillips needed to delay the pirates while naval assistance made its way to the ship. Tensions built and it became apparent that the pirates couldn’t hold the ship, so they escaped in a lifeboat with Phillips as hostage. The American navy and a team of SEALS mounted a rescue operation, determined to prevent the Somalis from reaching shore with their captive. (The film’s account is based on a book Phillips wrote about the experience, some of the details of which have been disputed by other crew members.)

Greengrass, keeping his flashy visual strategies more in check than in the almost unwatchable Bourne movies, recounts the story in a straightforward way, building tension through the events rather than overloaded camerawork and editing. This is essentially a “process” film, the characters sketched in sufficiently but without much depth; the focus is on the power games played by Phillips and the leader of the pirates, Muse (Barkhad Abdi), as they vie for control of the situation. Phillips, as played by Tom Hanks, is the epitome of calm, professional assurance, while the desperate young Somali becomes increasingly lost in a situation beyond his abilities to control; his second in command, the aggressive Elmi (Mahat M. Ali), quickly loses sight of the necessity of keeping Phillips alive for their own protection against the military forces gathering against them. Even if the outcome of the real events weren’t already known, it becomes clear quickly that the Somalis are doomed to fail; yes, their initial capture of the ship is effected relatively easily, the automatic weapons they carry guaranteeing at least a provisional capitulation by the crew. But there are just four of them on the vast ship and multiple, heavily armed warships on the way to intercept them.

Given this sense of inevitability, interest quite quickly comes to rest almost entirely on the character of Muse. Despite the early attempt by Greengrass and scriptwriter Billy Ray to set up some kind of parallel between Phillips and Muse (both are “trapped” by economic circumstances, Phillips in thrall to a vast corporation which shows no concern for the security of its employees, Muse forced at gunpoint by vicious warlords to attempt the hijacking), but it’s a phony connection. Phillips is a comfortable, middle-class American with a high-paying job he has chosen to do; Muse is an impoverished fisherman whose livelihood has been destroyed (the film offers in passing the observation that industrial fishing ships from other nations have obliterated the basis for his and his family’s traditional means of survival). No matter how sympathetic the film tries to make Phillips, he remains a figure from the world which has ruined Muse’s life.

Almost as if he senses this, Hanks keeps his performance low-key, allowing Abdi to hold our attention throughout – his performance is riveting and given the nature of the story, it’s quite remarkable that he becomes the most sympathetic character. It’s only after the climactic action that Hanks cuts loose at last to reclaim the film; his final scene as he’s being given medical attention and succumbs to shock in some ways seems like too much given the calm sense of control he’s maintained throughout. But there’s no denying that it’s a tour de force piece of acting (but not enough to win Hanks an Oscar nomination, though Abdi is up for Best Supporting Actor).

An Adventure In Space and Time

(Terry McDonough, 2013)

Also “based on actual events” is Terry McDonough’s An Adventure In Space and Time (2013), an account of the origins of Doctor Who (written by Mark Gatiss, surely the busiest man in British television). Written, directed and performed with genuine affection, this BBC-produced feature tells the story of how a small children’s TV show, created to fill a Saturday afternoon slot in the schedule, was conceived by ex-pat Canadian Sydney Newman (a ripe performance from Brian Cox) and put in the charge of a young woman with very little production experience. Verity Lambert (a charming Jessica Raine) had an uphill struggle on two counts: the BBC establishment viewed the proposed show as rubbish for children and she was a woman. She faces disdain at every turn as she pieces the production together, but gradually, under Newman’s tutelage, pulls all the necessary elements into place.

Gatiss’ script creates well-drawn characters and, perhaps more importantly, a richly detailed depiction of television production in England in the early ’60s, the pressure and technical complexities involved in shooting a show very quickly in cramped and inadequate studios – and in this case with the added technical problems presented by the sci-fi elements. While it works as an entertaining drama in its own right, Adventure also serves as a fascinating behind-the-scenes record of a show which unexpectedly became a hit and has lasted now for half a century.

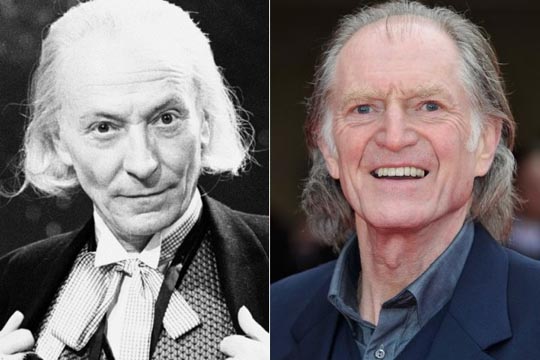

The cast is excellent, as are the production values, though I was a little disappointed with David Bradley’s performance as original doctor William Hartnell. Hartnell was a fine character actor with a long career (often typecast as petty criminals and military types), who was already in declining health when Lambert offered him the role; the three years he was on the show are legendary for the difficulties he presented the production team – cranky, irritable, flubbing lines – but on screen, he was critical to the show’s success, his personality holding Doctor Who together through its constantly shifting storylines and rotating supporting cast. Bradley does a fine job with Hartnell’s insecurity and failing mental powers, but he never quite captures the genuine depth and intensity of the actor’s performance as the Doctor (as can be seen by the brief glimpses of Hartnell on the disk in scenes which are recreated in the drama). But this is a minor quibble and An Adventure In Space and Time is a great reminder of the creative processes which went into the unexpectedly popular success of this kids’ show.

Karel Zeman x 2

The two latest releases from the Muzeum Karla Zemana in Prague represent two very different styles of filmmaking, reconfirming Karel Zeman’s remarkable skills and fecund imagination. Krabat: The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1978) is one of the most stylistically traditional of his films, using richly atmospheric painted backgrounds and articulated cut-out figures to adapt a novel by Otfried Preussler (who died just last year at 89). Krabat is a young orphan boy struggling to survive where begging and poverty have been made illegal. He’s lured to an old mill run by a sinister magician, who takes him on as one of twelve apprentices. It becomes apparent that a place to sleep and food to eat are not necessarily worth the cost as Krabat discovers that each year the eldest of the apprentices is given a chance to fight the sorcerer in a magical duel; to lose (as they inevitably do) is to die, with a new boy brought in to replace the dead one.

Despite the oppressive atmosphere at the mill and the threats of the sorcerer, Krabat meets and falls in love with a village girl. It’s no surprise to discover that this young love works as a potent antidote to the magician’s black magic, but Zeman’s visual imagination gives rich emotional life to the simple story.

The Stolen Airship (1967) is, like the earlier The Fabulous World of Jules Verne, a complex mix of live action and animation techniques. Like that earlier film, it evokes storybook illustrations (though in colour here) in its tale of five boys who steal an airship at a fair and eventually crash on a remote island (where they briefly encounter Captain Nemo and the Nautilus). Meanwhile, a newspaperman sets out to find the runaways, while spies, industrialists and eventually various military forces join the hunt, hoping to grab the secret of the airship’s supposedly experimental gas (which turns out to be a blatant con by the dirigible’s builder who temporarily makes a fortune by selling shares in his bogus company). The mixture of live action, painted backgrounds, sets which have the appearance of two-dimensional paintings, drawn animation, stop motion, and complex multi-element composites reconfirms Zeman’s place as a unique talent.

The Sicilian Clan (Henri Verneuil, 1969)

I know little about the French filmmaker Henri Verneuil. I vaguely recall seeing his Fernandel movie The Cow and I on television when I was very young, and I saw Weekend at Dunkirk in St. John’s, Newfoundland, in the late ’60s – very few memories of that beyond images of German planes strafing the beaches and the presence of 19-year-old Catherine Spaak (while she registered on my consciousness, I was perhaps too young and, at that time, disinterested in the finer points of cinema to note the presence of Jean-Paul Belmondo in the lead role).

I probably saw trailers for The Sicilian Clan (1969) during its original release, but for whatever reason I didn’t see the film at the time. On the recent recommendation of Glenn Erickson in a DVD Savant review, I ordered a copy of the new French Blu-ray edition – which contains both the French and simultaneously-shot English versions; although there were sound commercial reasons for these dual versions at the time, as with Rene Clement’s Rider On the Rain the French language version is the preferable one. There’s also an excellent one-hour retrospective documentary by Jerome Wybon about the making of the film.

The Sicilian Clan is a large-scale crime movie notable for its cast – the well-balanced narrative gives equal time to Alain Delon as the psychotic criminal Roger Sartet; the great Jean Gabin as Vittorio Manalese, head of a Sicilian family which hides its criminal activities behind a pinball machine business; and the equally great Lino Ventura as Commissaire Le Goff, the cop on Sartet’s tail after a daring jailbreak. Although all three stars had worked at various times for Jean-Pierre Melville and the narrative resides in an underworld which echoes many of Melville’s films, The Sicilian Clan lacks the depth and moral complexities of movies like Le Samourai, Le Doulos, Le Circle Rouge … but its two-plus hour running time is tightly constructed and well-paced, and it builds towards a genuinely audacious heist involving a commercial trans-Atlantic airliner which is handled by Verneuil with an air of easy assurance.

The core of the story involves the effect the brash Sartet has on the cautious Manalese, tempting the patriarch into a self-destructive situation with the promise of one huge take which will enable the old man to retire comfortably to his homeland. As with all such movies, the fun lies in the careful details of the planning and the inevitable unravelling of those plans; and as with the best such stories those details and the reasons for the plan’s ultimate collapse are rooted securely in well-drawn characters, their personal flaws and conflicts. The Sicilian Clan represents commercial filmmaking at its best.

Two Men In Manhattan (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1959)

Verneuil had a longer and more prolific career than Melville, but I’m more familiar with the latter’s work, having now seen eleven of his thirteen features, most recently Two Men In Manhattan (1959), given an impressive Blu-ray release by the Cohen Film Collection. To someone only familiar with the later crime films, this might appear as an oddity in Melville’s filmography; but his first five features, culminating in Two Men, reveal a varied and exploratory approach to movies – his first two features could easily be classed as “art films”, with his debut Le Silence de la Mer (1949) prefiguring his perennial interest in the French Resistance and the moral complexities of the Occupation which left a residual stain on French society for decades after the war, while Les Enfants Terrible (1950) pays homage to the poetic cinema of Jean Cocteau (on whose novel it was based). Two Men in Manhattan was made after a three-year break following Bob le Flambeur, the first of the signature Melville crime films.

Two Men is in large part an ode to the America which played such a significant, influential role in Melville’s work – that is, the dream of America seen on screen. The location shooting in New York is a fascinating document of that city on the cusp of the ’60s, mostly shot at night, combining street scenes packed with detail (I lost count of all the movie-house marquees) with a strangely fluid sense of the city’s actual geography, and interiors shot in-studio back in France. The mixture of French and American flavours gives the film the heightened reality we experience in dreams.

Melville himself plays reporter Moreau, assigned by his editor at Agence France Presse to track down the French delegate to the U.N. who failed to show up that day for an important vote. He enlists the aid of alcoholic photographer Pierre Delmas (Pierre Grasset), who seems to know pretty much everything about everyone in town. Together, they track down several women the delegate had been involved with – a Broadway actress, a burlesque performer, a prostitute, a jazz singer – each character permitting Melville to display a facet of the city’s vibrant life. When the truth about the delegate’s disappearance emerges, the two men are faced with a moral dilemma, to which they each react in radically different ways: Moreau sees covering up the facts as more important for a larger truth, while Delmas wants to exaggerate the details for profit. The conflict shatters their friendship, but in the end it’s Delmas who comes across as the film’s “hero”.

Beautifully shot in high-contrast black-and-white by Nicolas Hayer (whose career started in the early ’30s and included Clouzot’s Le Corbeau [1943] as well as Melville’s later Le Doulos [1962]), the film was nonetheless a financial failure when released and it was this that made Melville determined to become a “commercial” filmmaker. All his subsequent work, even the two features which touch directly on the Occupation and the Resistance (Leon Morin, Priest and Army of Shadows), focuses on the moral issues of crime, transgression, and the outsider’s struggle to maintain some kind of personal integrity in an unstable world within more familiar generic boundaries.

The Blu-ray includes a half-hour conversation between critics Jonathan Rosenbaum and Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, which is rather rambling and discursive, but offers some interesting insights into Melville’s career and this odd film in particular.

Comments