A picture needs a thousand words …

Flicker Alley, founded in 2002, is a company largely dedicated to restoring silent films, although they occasionally branch out (in the past few years with a series of Cinerama features in particular). Because of the somewhat specialized nature of their releases, prices tend to be a bit higher than average, so I’ve resisted buying a number of titles that intrigue me. But I did recently spring for their edition of an old favourite – The Most Dangerous Game (1932). This was the pre-Code horror film shot simultaneously on the jungle sets built for King Kong in order to get some quick return on the bigger film’s production costs while the lengthy animation schedule dragged on.

and Fay Wray

Based on the subsequently much-adapted short story by Richard Connell, produced by Merian C. Cooper and David O. Selznick and directed by Irving Pichel and Ernest B. Schoedsack, it stars Joel McCrae as Bob, a renowned hunter ship-wrecked on a remote island where he’s offered hospitality by the Russian Count Zaroff (Leslie Banks), who turns out to be a jaded, decadent aristocrat who can only work up enthusiasm for hunting human beings. When Bob reacts with disgust he finds himself and the also-stranded Eve (Fay Wray) struggling to survive in the jungle until dawn. Short, swiftly paced, with a degree of sadism which would not have been permitted a year or two later after the Production Code was brought in, The Most Dangerous Game has a primal quality which makes it one of the best adventures of its time. (It would make a great double bill with Island of Lost Souls.) Banks, just two years away from playing the hero of Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, makes a terrific villain in his first feature, oozing perverse charm and viewing his own sick game with jaded amusement.

Despite Flicker Alley’s restoration from a fine grain positive, which is brighter and sharper than the old Criterion DVD from 2001, the Blu-ray didn’t take my breath away (which is what I was unrealistically hoping for), but it does have a strong, informative commentary track by Rick Jewell, a USC prof, who goes into a lot of detail about this production and the careers of Cooper and Schoedsack in general.

Gow: The Headhunter (1931)

Quite unexpectedly, however, the disk acquires real interest from the presence of another short feature: Gow: The Headhunter (1931). This has been paired with The Most Dangerous Game because of what seems like a very tangential connection to Cooper and Schoedsack. The material of the film was shot on two expeditions in the early ’20s by one Edward A. Salisbury, an adventurer who saw the value of taking a camera along on his tours of the South Pacific and Indian Ocean – with the creators of King Kong briefly attached to one of the expeditions.

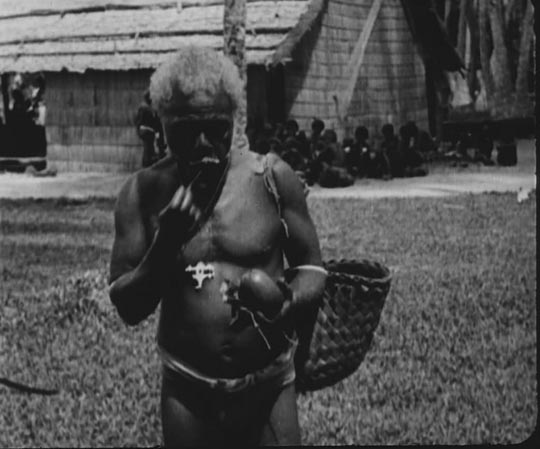

Gow is what Eric Schaeffer, in his fascinating study of exploitation films, Bold! Daring! Shocking! True! (Duke University Press, 1999)[1], calls “an exotic”. A haphazard collection of scenes of “primitive” people performing various rituals, staging scenes, or simply posing for the camera, its box office appeal lay in images of a world far removed from the small towns and cities of North America, with the added bonus of bare-breasted native girls. The film is crude, the activities depicted (fishing, tree-climbing, ritual dances, re-enacted battles) the kind of thing which would become familiar from the pages of National Geographic in subsequent decades. Originally released silent in 1928, narration was added in 1931 by expedition member William Peck. And this is where the film becomes interesting.

The old cliche has it that a picture is worth a thousand words. Of course, many pictures are all but unintelligible without words to give them context. The pictures in Gow, images of “otherness”, are given a context by Peck which strikes us now as utterly appalling. The relentless condescension and smug racism fight against pictorial qualities which offer no evidence for much of what Peck says … his characterization of the islanders as adults with the minds of three- and four-year-olds as we watch them perform complex ritual dances, build and sail sophisticated boats, and so on; and his rather sleazy dwelling on young naked women, making claims for their easy availability to anyone who comes along… The narration expresses the attitudes underlying European colonialism with its implicit justification of taking possession of these lands and putting an end to “primitive” practices.

Moving from what Peck calls the more civilized Marquesas through progressively “darker” lands – Fiji, New Guinea, the New Hebrides and the Solomon Islands – the film’s thesis is a kind of journey back through time to the savage origins of what would eventually become the pinnacle of human evolution, the white European. And naturally, those origins are mired in headhunting and cannibalism.

But Flicker Alley’s disk doesn’t stop there. Gow is accompanied by a commentary track by Matthew Spriggs, an Australian professor of archaeology, who carefully constructs an entirely different context for these same images. He points out what’s actually happening during the ceremonies; he indicates where Salisbury has staged things which have little bearing on the actual lives of the islanders; and he corrects numerous instances of complete misrepresentation – the headhunting which climaxes the film has totally different cultural and religious implications from those attributed by Peck. The words of the two separate commentaries have the power to completely alter what we see in the images. In effect, despite the genuine defects of the original material, Spriggs manages to transform Gow into an ethnographic work which has real value in its preservation of images of peoples and practices which would soon be irrevocably transformed by colonialism.

_________________________________________________________________

(1.) Schaefer’s book is highly recommended. Surveying exploitation films from World War One to the end of the ’50s, he uses these disreputable artifacts as the basis of a rich and detailed social history of attitudes towards sex, drugs, and “antisocial” behaviours which threatened the middle class’s sense of its rightful, dominant place in a hierarchy which was continually under threat from “others” (women, foreigners, irresponsible youth). It’s startling to realize how many of the attitudes which still shape out society were constructed almost a hundred years ago in attempts to impose standards of behaviour on a rapidly changing population (the image of marijuana as a social and moral evil, for instance, was concocted mostly in the ’20s and ’30s – concurrent with Prohibition – largely because of the weed’s association with non-white “others”).

A propos Gow: “Some exotics critiqued modernity and the demands of a consumer economy by playing on working- and middle-class fantasies that emphasized the utopian aspects of the jungle… A bit of fantasy about warm sea breezes, unlimited tropical fruits, and simple but attractive women could provide a brief respite from the rigors of work. But once the civilizing aspects of the time clock and job were rejected, it was a short step to the primitivism of human sacrifice, cannibalism, or even bestiality. Significantly, a number of exotic films – Gow, for instance – followed this pattern, moving from more ‘civilized’ and whiter peoples to darker, ‘uncivilized’ tribes… The Other was not simply black, not simply sexual in an unabashed way, but was, worst of all, unproductive.” (page 281) (return)

Comments