Documentary and the evolution of movies

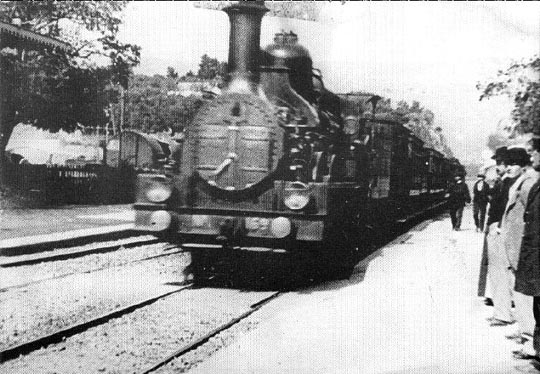

One of the things that has emerged from my recent posts inspired by the “Greatest Documentaries of All Time” list published by Sight & Sound is that it’s not always clear just what constitutes “documentary”. This ambiguity has been embedded in film since the medium’s invention. The very first films were what we now call “actualities”, single shots of a particular event, person or action – workers exiting the Lumiere factory, a train arriving at a station, and so on. These very ordinary things were initially sufficient to hold an audience’s attention, which is a strange thing if you think about it: those audiences could see these things every day during the normal run of their lives, and yet seeing them projected in black and white and two dimensions on a screen held a deep fascination. Stories (possibly apocryphal) of people screaming and fleeing the theatre when that train raced towards the camera on the platform at the station in La Ciotat suggest a fundamental difficulty in separating photographic representation of action from the action itself. This psychological phenomenon has underlain much of film history, providing the means by which those projected illusions can elicit such intense responses from viewers; it has permitted all manner of audience manipulation, imbuing film with a peculiar mixture of power and uncertainty. We respond to movies on a physical as well as emotional and intellectual level.

and (below) messing with the gardener

The photographic aspects of the medium point towards objectivity or “truth”, while the manipulative aspects (shot choices, editing, camera tricks, etc) undermine that air of truth. We love to be manipulated and made to feel, but we always remain to some degree aware that what we are seeing is not in fact objective. This combination of objective and subjective was exploited very quickly by early filmmakers, who introduced elements of staging into those actualities, creating fictive moments which were nonetheless initially observed with the same static neutrality (the Lumieres’ visual gag of a boy interfering with a gardener’s watering hose). Not surprisingly, the element of voyeurism quickly entered the mix, with audiences permitted to observe in safe anonymity a kiss, a suggestive dance, a shoe salesman fetishistically fondling a woman’s foot. The viewer of a movie projected on a screen in a dark theatre was now able to see things which it would be improper to stare at in real life (a fact which was quickly exploited by pornographers and just as quickly gave rise to widespread efforts to control and censor moving pictures).

and (below) the Klan’s retribution

Satisfaction with simple actualities and brief staged moments soon diminished and filmmakers responded with the rapid development of increasingly sophisticated techniques – the use of multiple shots and editing (at first mostly static proscenium images strung together, but soon evolving into more elaborate combinations of wide, medium, close-up) to enhance the action and to provide more complex virtual experiences. Within this development, the tension between the documentary element (the observation of real places and real people) and the narrative element (often, before studios were built, also shot in real places and, of course, featuring real people, who nonetheless were playing fictional characters) remained a powerful factor – this was integral to the impact of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), which recreated with remarkable fidelity the photographic “reality” familiar to viewers from the work of Civil War photographer Matthew Brady; it was this visual authenticity which provoked intense protests from some parts of the audience while drawing praise from others. It seemed to add validity to Griffith’s contentious, racist treatment of Blacks during the Reconstruction, which in turn prompted a massive revival of the Ku Klux Klan by seeming to justify a violent “defence” of white society against the unleashed primitivism of freed slaves and their descendants. President Woodrow Wilson’s reputed comment that the film was “history written with lightning” validated the documentary appearance of the images while eliding the underlying ideological manipulations of the narrative.

One of the pleasures of early film is the ease with which filmmakers would move between forms. The British pioneer R.W. Paul produced numerous actualities as well as some of the earliest fiction films (including possibly the first British narrative, A Soldier’s Courtship, in 1896); he made newsreels of prominent events like the annual Derby (which could be screened just a day after the race for enthusiastic audiences for whom the event itself was out of reach) and Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Paul also re-staged events from the Boer War, blurring the lines between drama and newsreel, as well as making fantasies much like those of Georges Melies, utilizing elaborate trick photography. In those first years of cinema, the medium seemed infinitely malleable.

While filmmakers like Griffith were working hard to perfect the mechanisms of convincing illusion, others were content to record reality, to document the world around them. In England, for instance, in addition to R.W. Paul we have the pioneers Sagar Mitchell and James Kenyon, who traveled around the country shooting local scenes and events, quickly processing the film on site and offering showings sometimes the same evening at which ordinary people could see themselves up on the screen; and Claude Friese-Greene, an innovator with colour, who created vivid travelogues around the country in the mid-’20s. But many of the more ambitious films of the silent and early sound periods couldn’t resist introducing narrative elements into the documentary record: Flaherty in Nanook of the North (1922) and even more so in his later collaboration with F.W. Murnau, Tabu (1931); Henry de la Falaise de la Coudray in Legong (1935); and Flaherty again in his collaboration with Zoltan Korda, Elephant Boy (1937). Many of these films emphasized the exotic, the difference between “primitive” cultures and European “civilization”, with a mixture of envy and nostalgia for what was somewhat condescendingly seen as a pre-industrial innocence.

This quest for a more rugged and primal existence, a powerful thread which runs through 19th Century narratives of exploration, was given renewed life by the invention of cinema which provided a more vivid experience for ordinary people who seldom ventured far from home than was possible in written accounts. Despite the obvious hardships depicted in films like Merrian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack’s Grass (1925) and Chang (1927), there was an undeniable romantic appeal for audiences whose lives were constrained by a modern urban, industrial existence.

Documentary and Exploration

Three wonderful feature-length examples of the evolution of documentary are available from the BFI, beginning with their 2002 DVD edition of Frank Hurley’s South (1919), a filmed record of Ernest Shackleton’s Antarctic expedition of 1914-15 (a disk which calls out for an upgrade to Blu-ray [this upgrade finally arrived in February 2022]). Hurley, a superb photographer, approached the task of documenting the expedition in the spirit of the actuality; his film often plays as a series of magnificent stills within which we catch glimpses of motion. Much of it displays the landscapes, the wildlife and plants observed, rather than the drama of the expedition (very well evoked, using much of Hurley’s footage, by George Butler in his 2000 documentary The Endurance). An understanding of film history may be required for a contemporary audience to appreciate fully a work like South; inundated as we are today with spectacular HD nature and travel films, the remarkable achievement of someone like Hurley, working in incredibly harsh conditions with “crude” equipment to produce such artful images, might not at first be apparent.

In 2011, the BFI released a Blu-ray edition of Herbert Ponting’s The Great White Silence (1924; re-edited with sound as 900 South in 1933), a documentary filmed during the 1910-13 British Antarctic expedition led by Robert Falcon Scott. Again made under extreme conditions, Ponting’s film strives more than Hurley’s to create a narrative, including elements of staging which are used to give the impression that Ponting went along on the final push to the Pole, although he actually remained behind at the base camp. This film did much to solidify the heroic image of Scott, despite the fact that his poor leadership led to the deaths of himself and several of his men (while Shackleton’s brilliant leadership, in contrast, preserved the lives of his entire team despite their being stranded for two years in brutal conditions on the ice: I didn’t even hear about Shackleton as a child in England, where Scott was paradoxically revered as a national hero).

The Epic of Everest (1924)

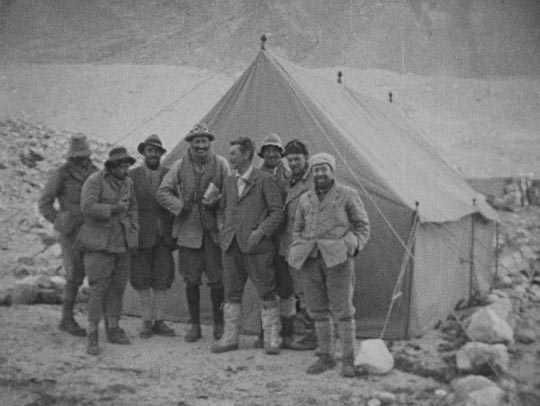

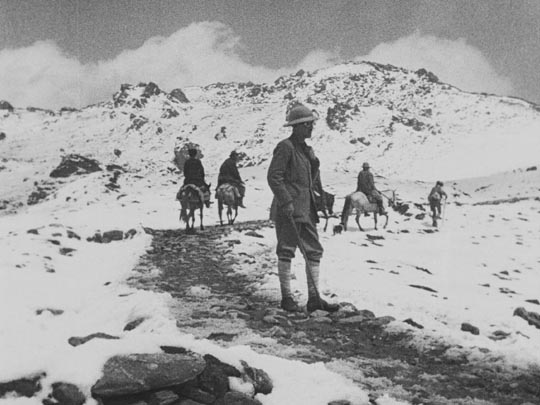

With the release this year of a restored version of Captain John Noel’s The Epic of Everest (1924), the BFI caps this trilogy of exploration documentaries with one of the most cinematically accomplished films in the genre. Noel, a great technical innovator, goes far beyond the simplicity of actualities and eschews awkward attempts to construct dramatic scenes, and his film offers an awed response to one of the harshest environments on the planet. Perhaps the thing which distinguishes this film so clearly from Hurley’s and Ponting’s is the way in which Noel is willing to hold a shot for a long time, adding a genuinely cinematic sense of duration which immerses the viewer in the dramatic landscapes, producing a greater sense of respect for the men facing that environment.

In addition, Noel modified his camera so that it could be operated either by hand or with an electric motor, the latter enabling him to shoot time lapse images of the Himalayas, displaying the movement of clouds and the changing play of light across glaciers and among rocky peaks, which remain impressive today. He also built his own telephoto lens which enabled him to catch images of the climbers heading for the peak of Everest from a distance of three miles; these images of those tiny figures moving along vast blinding ridges of snow and ice speak volumes about the disparity between fragile human beings and this imposing environment.

The Epic of Everest, with its depiction of brave exploration and tragedy coming so soon after the slaughter of the Great War, offered a narrative of redemptive sacrifice, of men giving their lives for a noble cause in contrast to the waste of the war, and the film was a huge success with audiences despite the “failure” of the expedition (it remains unknown whether George Mallory and Andrew Irvine managed to finish their climb or died before reaching the peak, and the final image of the men disappearing over that ice ridge in the distance has a poignant inconclusiveness).

From the perspective of the history of film production, the making of The Epic of Everest is as interesting as the film itself. Noel had previously gone to Everest on a preliminary expedition in 1922 and, by selling shares in his proposed film of the first attempt on the peak, actually became the primary funder of the 1924 expedition, putting in an impressive £8000 in exchange for exclusive rights to the filmed record. In effect, here the filmmaker was instrumental in creating the event which he was documenting, recouping his investment through subsequent screenings in England and America.

Viewed now, ninety years later, this innovative film is clearly rooted in the 19th Century impulse of exploration which in turn was inextricable from the impulses of European imperialism. In its first half, the film depicts the people of Nepal as strange specimens of “the other”, with a mix of fascination and condescension. These attitudes extended to the film’s exhibition as screenings were prefaced with “performances” by a group of Tibetan monks. The film’s images and these touring monks, feeding the British and American interest in strange, far-off places, had an unintended consequence (which we might see as inevitable, but which didn’t occur to Noel and his partners because of their imperialist blind spot): the Tibetan authorities were deeply upset by what were perceived as offensive depictions of the local population and even more offended by the reduction of sacred religious rites to music hall performance, and any further expeditions to the mountain were banned for many years (Everest wasn’t officially “conquered” until Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay reached the peak in 1953).

Noel’s remarkable documentary thus derailed efforts to accomplish the very thing it was made to promote and achieve. Wade Davis, in a fascinating essay in the booklet accompanying the BFI disk (adapted from his book Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory and the Conquest of Everest, 2011) goes even further, proposing that the reaction to the film helped to entrench a conservative establishment in Tibet, stalling efforts at modernization, and thereby laying the mountain kingdom open and vulnerable to invasion and colonization by China in 1950. If valid, this argument illustrates a remarkable relationship between documentary and reality, a confirmation that documentary is never merely a record of what it takes as subject, but is always implicated as an active participant in the world it explores.

Comments