Recent Viewing: more horror from Arrow

English speakers, particularly in North America, tend to be uncomfortable with the kind of absurdity and uncertainty seen in gialli and J-horror; they need explanations, comprehensible motivations (at least, that’s what producers and distributors believe) – which is why U.S. remakes of Japanese horror films never really work. The Americanized versions of Ringu and Ju-On replace the deeply disturbing mystery of the originals with rationalizations which insist that the supernatural is ultimately knowable, apparently unaware that this dissipates the horror which makes the Japanese films so wonderfully creepy. I’ll make a sweeping generalization here and propose that this difference in attitude often gives a very different flavour to English-language horror films (though there are rare exceptions like Wes Craven’s original Nightmare on Elm Street, which definitely has moments similar to Japanese ghost stories). At some level this is rooted in very different cultural attitudes and philosophies; we tend to be more prosaic, less inclined to see the world permeated with spiritual forces. As a result there tends to be something more physical about our horrors (reduced at its worst to the graphic sadism of the Saw and Hostel movies).

This is one reason why so many North American horrors are prefaced with an assertion that they are “based on a true story”. We are drawn to the idea of realism, regardless of how far-fetched the story might actually be. We need to have this “factual” justification for our thrills. How else to explain the many uses to which real-life killer and (possibly) necrophile cannibal Ed Gein has been put since his unsavoury deeds were exposed in the late ’50s? This degenerate from rural Wisconsin, whose mother fixation and loneliness led him first to raid local graveyards and fill his remote farmhouse with corpses and various artifacts made from body parts, and later to commit a couple of murders (his body count was actually very small compared to many other serial killers), was first used by Robert Bloch as a starting point for his novel Psycho, which in turn became the source for one of Alfred Hitchcock’s most celebrated yet controversial films. In the ’70s, the case became the purported source for Tobe Hooper’s landmark Texas Chainsaw Massacre, although there was even less relation to the original than there had been in Bloch and Hitchcock’s version. Elements of Gein’s story strongly influenced The Silence of the Lambs and there have been numerous attempts to tell “the true story” over the years … but none have come as close to a small, low-budget, shot-in-Canada feature released eight months before Hooper’s more famous movie.

Deranged (1974)

Deranged was the work of writer Alan Ormsby (who co-directed with Jeff Gillen), who had previously collaborated with Bob Clark on Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things (1974), the first movie to apply a self-reflexive comedic approach to the nihilistic zombie genre established by George Romero with Night of the Living Dead. Cheap and rather crude, Children was a precursor to The Evil Dead (1981) and Return of the Living Dead (1985). Made just a year later, Deranged was a huge step forward for Ormsby; the script adheres fairly closely to the actual story of Gein (here called Ezra Cobb) and is generally shot with a fine eye for naturalistic detail even as events become increasingly – well, deranged.

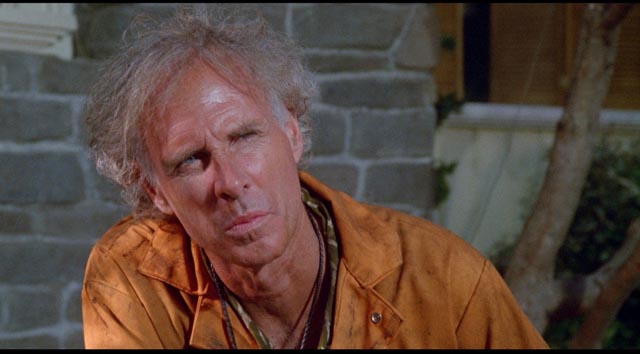

Cobb (a remarkable Roberts Blossom) is a mentally and socially backward man who has been fiercely dominated by his mother (a chilling Cosette Lee), a woman who has drilled into him that all women are evil and to be avoided. She has kept him tied closely to her into middle age and when she dies, he’s suddenly cast adrift, alone and incapable of engaging with other people – the film has a great deal of humour arising from his social incompetence, including a tendency to openly tell people about the things he’s doing; his deadpan delivery is received as warped humour by people who view him as simple-minded and harmless. Unbalanced by being left alone, he eventually digs up the decaying corpse of his mother and takes her home where, like Norman Bates, he has mother-son conversations with her, receiving warnings and guidance as he becomes awkwardly attracted to local bar waitress Mary (Micki Moore).

Given that the two films were made completely independently, it’s surprising how many echoes there are between Deranged and Texas Chainsaw Massacre, particularly in the grotesque sequence in which Ezra lures Mary to his farm and introduces here to a dining room full of decaying corpses, his “family”. The house is decorated with bones, skulls, things made from dried human skin … very much like the farmhouse in Hooper’s film. And like Leatherface, Ezra dresses in a skin mask (adding breasts, a human-scalp wig, and a dress). Mary’s attempts to escape are as harrowing as Sally Hardesty’s in Chainsaw, but she’s not as lucky.

Ezra’s grip on reality slips even further as he kidnaps young store clerk Sally (Pat Orr); when she manages to get away from him, he hunts her like a wounded deer through wintry woods, leading to the film’s final horrific images (based on actual photographs from Gein’s farm). The film is carefully and effectively directed, but its lasting value rests with Roberts Blossom, who gives the performance of his long career (though he didn’t like the finished film); Ezra is so believable, so human in his madness that he remains strangely sympathetic even as his behaviour becomes more dangerous and twisted.[1]

The oddest element of the film is a device used by Ormsby to frame the story – the on-screen presence of Tom Sims (Les Carlson), a reporter who pops up at the oddest times as scenes freeze in tableaux to give him space to comment on Ezra’s doings. This device is generally criticized as an inexplicable creative error; I suspect it was intended as a kind of Brechtian alienation device, a deliberate attempt to create critical distance between the audience and the more extreme events depicted, but also as a safeguard against possible censorship problems by trying to establish the film’s nature as a report on actual events, rather than as a piece of sordid exploitation. And yet even though it doesn’t really work as a device, it adds an interesting note to the proceedings anyway.

The Arrow Blu-ray makes the film look as good as it probably ever has, with a colourful, textured image. There are three short featurettes: one with Scott Spiegel talking about Roberts Blossom (who had never seen the film until Spiegel gave him a VHS copy on the set of The Quick and the Dead; Blossom returned it the next day saying he never wanted to see it again); a short making-of; and an odd interview with Laurence R. Harvey, star of Tom Six’s Human Centipede 2: Full Sequence, who talks about Gein, his influence on the movies and most specifically how Blossom’s performance influenced Harvey’s choices as an actor portraying a deranged killer in Six’s film.

Finally, there’s a chatty commentary with Tom Savini (who did the make-up effects on Deranged as well as the Ormsby-Clark follow-up Dead of Night [also 1974]) and Arrow’s supplements producer Calum Waddell. The conversation wanders far from Deranged at times as it covers Savini’s career, and the pair sometimes seem to be caught by surprise by what’s going on on-screen; it might have been nice if they’d taken the trouble to re-watch the film before recording as they occasional question each other about what’s happening and at times misinterpret the film’s events (during Ezra’s hunt for Sally in the woods, they complain about the screen time wasted on the pair of hunters who have set the trap which seals her fate, apparently unaware that these men are Sally’s boyfriend and his father, an added layer of distressing irony).

*

The ‘Burbs (1989)

Although Joe Dante has frequently worked in the horror genre from the start of his career with the Roger Corman-produced Piranha (1978), he has always tempered the scares with humour; films like Piranha and The Howling, despite an edge of nastiness, linger in memory more as comedy than nightmare. In fact, much of his work is characterized by complicated shifts of tone which in an industry given to adhering to audience expectations has prevented him from becoming a major mainstream director despite his obvious talent – his biggest hit, Gremlins, managed to conceal some rather nasty and violent undertones beneath its kids’ film puppet-dominated surface.

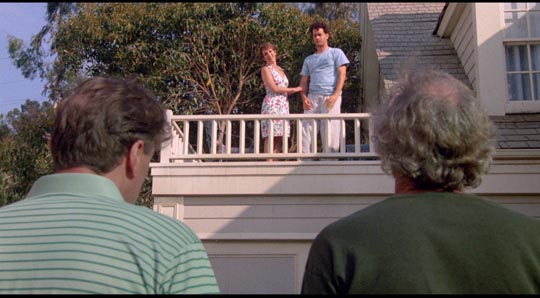

The ‘Burbs, an entertaining failure, again mixes horror and comedy, the tension between the two resulting in an awkward inability to resolve the narrative. Tom Hanks, on the cusp of success, stars as man-boy suburbanite Ray Peterson, who happens to be spending a week at home from his unspecified job. He and his neighbours Art Weingartner (Rick Ducommun) and Lt. Mark Rumsfield (Bruce Dern), having nothing better to do, become obsessed with some mysterious new neighbours, the Klopeks, who are seldom seen outside their dilapidated house from which strange lights flash at night. With echoes of the famous Twilight Zone episode The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street, Dana Olsen’s script exposes the paranoia which festers beneath the complacent lives of these suburbanites.

For much of its length, the film is quite funny, with fine comic work by the stars (Carrie Fisher as Ray’s practical, fully-grounded, frequently exasperated wife, is a stand-out). The comedy revolves around the distrust of difference – the Klopeks are an odd bunch who make no effort to fit in, which is itself a cause of distrust. Unsurprisingly, the film climaxes with a big action set-piece which involves the guys blowing up the neighbours’ house. Here, the script makes its explicit point about xenophobia as Ray finally gains some self-awareness and makes an impassioned speech about how he and his buddies are the monsters, that their paranoid fantasies have driven them to destroy the home of their neighbours.

But then, needing a less downbeat ending, the movie suddenly kicks back into gear and it turns out that the Klopeks really are dangerous, even murderous, madmen (it’s never clear what they’re really up to), abruptly reversing the point which has just been made by now justifying the men’s paranoia as a rational distrust of difference. This reactionary reaffirmation of prejudice leaves a sour taste. Leaning much more on comedy than horror, The ‘Burbs ultimately can’t resolve Dante’s signature tonal shifts, but much of it remains quite entertaining.

The Blu-ray image looks very good and once again Arrow has packed the disk with extras, including a commentary with writer Olsen (who doesn’t make much effort to justify the ending other than saying that Ray’s speech is the film’s emotional climax while the rest is just commercially-dictated story business); a feature-length making-of; an alternate ending; a complete workprint cut (from VHS) which differs from the theatrical; and a featurette comparing the two versions.

*

Mark of the Devil (1970)

The madness of witch-hunting which plagued Europe (and to a lesser degree colonial America) for centuries stands as one of the worst examples of the nastiness human beings are capable of inflicting on one another. Interestingly, at the end of the ’60s there was a flurry of productions which treated the subject with seriousness as a historical and psychological phenomenon. There were three in particular, beginning with Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General in 1968 and climaxing with Ken Russell’s masterpiece The Devils in 1971 (four, if you count Piers Haggard’s Blood on Satan’s Claw, although that one stands apart in its use of genuinely supernatural elements), which skirted censorship restrictions with their depictions of madness and torture; in between came the most notorious – Mark of the Devil (1970), the second feature directed by writer Michael Armstrong, whose credits include scripts for sex comedies, a couple of lesser Pete Walker features and Ian Merrick’s brilliant The Black Panther (1977).

If Mark of the Devil has less of a reputation than either Reeves’ or Russell’s films, this is primarily due to the nature of its production; it doesn’t look like an English movie because it was shot in Austria with a multi-national cast, many of whom were dubbed. This gives the film the slightly disreputable air of Euro-sleaze. Armstrong was brought in when much preparatory work had already been done and original writer-producer Adrian Hoven fought with the English director throughout the shoot. The original script had conflated witch-hunting with vampires, but Armstrong ditched the fantasy element and introduced a great deal of historical detail, filling the film with social, political and psychological verisimilitude which is only partially vitiated by the production’s shortcomings.

Although the film’s setting and period are rather vague, those details give a solid foundation for the more exploitable elements. The sexual pathology of the witch-hunter Lord Cumberland (an authoritative Herbert Lom), which is absorbed into a religious fanaticism, draws strongly from the appalling manuals written in the middle ages (anyone who has tried to read the Malleus Maleficarum will find it a stiflingly pathological document which dresses its sadistic hatred of women in righteous religious terms); the hypocrisy of Cumberland is laid bare through the presence of a secondary, less concealed, character, the self-appointed Albino (Reggie Nalder) who has taken up witch-hunting for profit and sexual gratification. It’s through the clash of these two that Cumberland’s adoring acolyte Christian (Udo Kier) comes to see the truth about his master and understand that his victims are not the monsters he’s been led to believe.

Added to the central thread of the narrative are supplementary storylines revealing the range of the mania and its underlying principles, particularly in the story of Baron Daumer (Michael Maien) who has been arrested and tortured in an effort to get him to sign his lands over to the Church. There are also a nobleman and his wife who are discovered by Albino’s ignorant and superstitious minions performing a puppet play for their children and arrested (the “talking” puppets are seen as demonic manifestations). Even though Cumberland recognizes the absurdity of this, the system he’s implicated in can’t afford to admit mistakes and so the couple must nonetheless be tortured and condemned. The key moment in the film comes when Christian questions the justification for torturing and executing innocent people. Cumberland replies that, well, if they’re innocent they will be God’s martyrs. Christian responds that if they are indeed martyrs, what does that make of their persecutor Cumberland? There is no answer.

There are scenes of graphic torture in Mark of the Devil, all performed with actual instruments from the museum in the Austrian castle where much of the film was shot, and it was these scenes which kept the film off British screens and prevented its release in an uncut form until Blue Underground’s DVD edition a decade ago, now much improved on by Arrow’s Blu-ray. Less polished than Witchfinder General and less artful than The Devils, Armstrong’s film is nonetheless like them a grim downer, its depiction of these real-life horrors vitiating the kind of exploitative titillation Hoven tried to graft onto it. It serves as an effective primer in the events of three centuries during the Middle Ages and Early Modern period, in which hundreds of thousands, possibly millions, were executed for witchcraft and heresy.

As expected, Arrow’s Blu-ray looks very good and is packed with extras. There’s a fine commentary in which Armstrong chats with Calum Waddell, recounting his various conflicts with Hoven and his efforts to make the depiction of events as authentic as possible. A long-form documentary situates the film in the British horror scene of the time, while a shorter piece examines the marketing efforts of U.S. distributor Hallmark when the film was released in the States (“rated V for Violence”, with complimentary vomit bags handed out to patrons). There are interviews with composer Michael Holm and a number of the actors (Udo Kier, Herbert Fux, Gaby Fuchs, Ingeborg Schöner and Herbert Lom), some outtakes and a featurette which returns to the film’s locations in Austria.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) A more recent film which shows traces of the Gein story, James Franco’s adaptation of Cormack McCarthy’s Child of God, also manages to find empathy for a dangerous, socially isolated character; Lester Ballard (Scott Haze, as chilling yet sympathetic as Blossom) lives like an animal outside a community which has no idea how to deal with his apparent madness, and loneliness leads him deeper into aberrant behaviour, with murder and necrophilia coming to seem like an understandable response to his isolation. (return)

Comments