Watching Horror

Watching horror, like watching war films, is a way to experience fear without actually being vulnerable. Vicarious thrills allow us to indulge emotions which, in real situations, would be very unpleasant. We always have the guarantee of personal survival, the threats contained within structured narratives which, traditionally, provided us with a way back to normality. Of course, post 1968 and Night of the Living Dead, this escape clause has been largely compromised, as many horror movies deliberately leave us on edge with unresolved situations and the idea that the horror can have no end. But then, as often as not, that idea gets watered down with the literal reiteration of the horror through endless sequels. Franchise horror by its very nature becomes reassuring and as often as not ends up mocking itself by turning its fears into comedy – the increasing absurdity of Jason’s exploits, Freddy Krueger’s snappy wisecracks, and so on. Horror becomes a game played with a faithful audience.

I confess that I was never a fan of one of the most influential franchises: Halloween. I’ve liked a number of John Carpenter’s movies, starting with Dark Star and Assault on Precinct 13, both of which play very smartly with genre conventions. His masterpiece, The Thing, remains the finest monster movie ever made. But Halloween has always left me lukewarm at best. His use of widescreen, his skill with moving camera – even his knack for repetitive synth themes which get under your skin – are undeniable, but the 1978 movie is a mere construction of mechanical scares, with endlessly repeated glimpses of a van passing in the background, a figure standing across the street staring, shadows that appear and disappear, all impinging on deliberately mundane high school tropes played out by actors already too old for their parts. The most entertaining element in the movie, not surprisingly, is Donald Pleasence’s overwrought turn as psychiatrist Sam Loomis, a man driven to the edge of madness himself by his obsession with killer Michael Myers.

But Michael is nothing more than a symbol, a literal boogeyman with no personality, no motive, nothing except a plot-driven urge to kill. Why does he come back to Haddonfield? Why does he target this particular set of high schoolers? No reason, he’s “just evil”. This vagueness, for me at least, is an irritation. Michael begins as a little boy who inexplicably stabs his sexually active sister to death; then he grows up to be a monster with supernatural overtones. But Carpenter, grounding the film in the mundane, fails to account for the increasingly symbolic function of Michael. It’s this vagueness which paved the way for the much-derided explanations in subsequent instalments (the whole Laurie-is-Michael’s-sister thing introduced in Halloween 2). When Carpenter left things unresolved at the end of the first film, he was aiming for the same kind of open-ended unease Romero had shocked audiences with in Night of the Living Dead; the inevitable process of the sequels was to seek ways to explain something which was at its core inexplicable. (Romero has been far more successful with the metaphorical implications of his zombies.) But, as in the even messier Friday the 13th series, no matter what new writers and directors attempted, the menace always remained a vacuum, a hulking silent killing thing without even the relief supplied by Freddy Krueger’s verbal games.

Rick Rosenthal’s Halloween 2 merely replayed the ideas of the first film, with the addition of that out-of-nowhere thing about Laurie being his sister. Realizing that the storyline had been played out, Carpenter as producer sought to redirect the budding franchise into new areas by having the great British genre writer Nigel Kneale come up with an entirely original script for Halloween 3. As is well known, this didn’t end well; Kneale’s script was rewritten by Tommy Lee Wallace, who went on to direct Season of the Witch. Although Kneale was dropped from the project, the broad outlines of his work are clearly visible in the finished film, with its links to ancient Celtic magic and the use of a powerful stone relic to power a scheme to bring on the apocalypse on Halloween night by triggering psychotic violence in kids wearing masks manufactured with built-in microchips. There are traces of Kneale’s Quatermass stories, The Stone Tape, and others, but in Wallace’s script this is all undermined by cliched characters and situations.

The relative failure of Season of the Witch sent the producers back to Michael Myers; in Dwight Little’s Halloween 4, Michael wakes from a coma and returns to Haddonfield to kill his niece. Having yet again cheated death, Micheal comes back in Halloween 5 to attack family members again. Somewhere in here, his evil becomes infectious, contaminating his young niece. In Joe Chapelle’s Halloween 6 (The Curse of Michael Myers), some of Kneale’s ideas are reintroduced, with Michael being manipulated by a cult of Druids paving the way for the rebirth of a pagan god. With the rapidly escalating silliness, it was probably inevitable that the franchise owners would try for something like a reboot; this came with Friday the 13th veteran Steve Miner’s Halloween H20, which essentially wiped away the previous four movies and followed directly from Halloween 2, picking Laurie Strode up twenty years after her ordeal; running a private school and trying to over-protect her son, she suddenly finds herself dealing with the return of her homicidal brother, who starts cutting his way through the students it’s her job to protect. After all the nonsense of the previous fifteen years, H20 actually seems almost refreshing, a nostalgic return to old-school ’80s slasher horror. But that was the year Hideo Nakata’s Ringu introduced a whole new style of horror to North American audiences and the year before The Blair Witch Project would usher in a new home-grown style; the old psycho killer was being firmly displaced by supernatural forces which undercut everyday life.

All of this comes to mind as I’ve recently revisited the entire Halloween series on Blu-ray (up to and including the dismal eighth movie, Rick Rosenthal’s pathetic Halloween: Resurrection [2002]), taking another look because I wondered whether I might have been missing something all along, given the franchise’s long-running popularity. I remain unconvinced.

I made no attempt to rewatch Rob Zombie’s abysmal remake, which unlike the original went out of its way to try to explain Michael’s psychology. As for Zombie’s Halloween 2, I’ve never been able to sit through it even once.

Having said all this, the completist in me was quite impressed with the hefty 15-disk Halloween set from Anchor Bay and Shout! Factory, which includes far too many extras to mention, although I might single out the alternative (producer’s) cut of Halloween 6, which isn’t any better than the theatrical release, but does illustrate the kind of thinking a distributor applies to a commercial property like this. The theatrical cut is so stripped of character detail in an attempt to “get to the story” more quickly that it becomes almost incoherent. With those details put back into the producer’s cut, the story is just as silly, but at least it can breathe a little more. The question is, why did the distributor cut it so severely? Was it because they recognized the silliness and thought they could disguise it by making everything move by more quickly? Or was it just another case of suits mistakenly thinking that audiences looking for mindless distraction won’t sit still for narrative?

Other than the occasional shock scare, the entire Halloween series doesn’t offer much to get under a viewer’s skin and leave a lasting impression. Which is what I always look for in a horror film; I want to be creeped out and disturbed (the larger question of why is something I’ve never found a satisfactory answer for). A couple of recently watched features provided a little of this.

*

Stuart Gordon’s Dolls (1986), his third feature after Re-Animator and From Beyond, was a nice surprise, a genuinely creepy fairytale made with style and humour, which replaced the gross-outs of the previous films with atmosphere and some attention to character. A kind of update of Hansel and Gretel, it has a vacationing family stranded in the English countryside and taking refuge in a gloomy mansion inhabited by toymaker Gabriel Hartwicke (Guy Rolfe) and his wife Hilary (Hilary Mason). The vacationers are a really unpleasant couple, David Bower (Ian Patrick Williams) and his vicious second wife Rosemary (director Gordon’s wife Carolyn Purdy-Gordon), and David’s eight-year-old daughter Judy (Carrie Lorraine). The couple hate being burdened with Judy and she hates being forced to spend the summer with them, away from her mother. Just as everyone settles down for dinner, out of the stormy night come goofy Ralph Morris (Stephen Lee) and two punkish hitchhikers, Isabel (Bunty Bailey) and Enid (Cassie Stuart).

Judy, the most observant person present, begins to notice odd things, but her parents refuse to pay attention. When the two hitchhikers set out to steal stuff from the old couple, something attacks them. Judy finds an ally in the childlike Ralph, but her parents accuse him of being a pedophile and order him to keep away. The threat in the house comes from Gabriel’s dolls, an impressively designed collection of creepy figures who come to life and attack anyone they deem “bad”; Judy and Ralph’s innate innocence protects them, while the others are picked off one by one. The dolls themselves are given disturbing life by Gordon and his effects crew, reawakening memories of childhood unease inspired by the uncanny appearance of these miniature, life-like yet not-alive toys.

Apart from the fine effects and the presence of pros Rolfe and Mason, who obviously relished their roles as fairytale witches, the film’s real strength rests on the shoulders of eight-year-old Carrie Lorraine, who gives a remarkable performance as Judy. Strangely, despite her obvious talent, this was her final credit (after a couple of TV appearances and a bit part in Poltergeist 2). She grew up to become a lawyer.

*

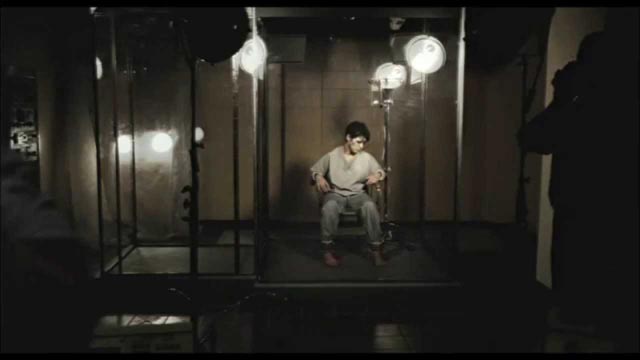

Chris Sparling’s The Atticus Institute (2015) comes from the opposite end of the stylistic spectrum; instead of the lush fiction of Dolls, it uses faux documentary techniques, including archival footage and talking-head interviews, to tell the story of a secret parapsychology experiment in the mid-’70s which went horribly wrong. Dr. Henry West (William Mapother) is running a research department which is trying to prove and quantify extrasensory perception. When the obviously disturbed Judith Winstead (Rya Kihlstedt) turns up, she exceeds all the researchers’ expectations. So much so, that government agents move in to take over and lock down the project. West tries to maintain control, but conflicts arise among the staff and he gets pushed aside as it becomes clear that those government agents want to groom Judith as a weapon – the perfect assassin and saboteur; unfortunately they have no idea what they’re dealing with. It turns out that Judith may be possessed and the experiments conducted on her merely give added strength to whatever force has taken over.

There may be nothing terribly original about The Atticus Institute, but for the most part Sparling (whose most notable previous credit is for the script of Rodrigo Cortes’ Buried [2010]) makes the most of what he’s working with. The documentary conceit holds up quite well and Kihlstedt gives an intense, disturbing performance. At times, the film reminded me a little of Les documents interdit, a series of eerie found-footage shorts by French filmmaker Jean-Teddy Filippe. Although the whole found-footage thing has been so overdone in the past few years, it still has the potential to disturb when handled well and The Atticus Institute is one of the better recent examples of the genre.

*

But for that true frisson that digs deep under the skin, I can’t think of anything in the past few years which has had the impact of a two-minute short on YouTube which my friend Steve showed me recently when we got together for an evening of viewing. I had just introduced him to J.T. Petty’s underrated western-horror hybrid The Burrowers (which also features William Mapother) on Netflix and he reciprocated with Lights Out by David F. Sandberg. There’s something so primal about this little movie that the viewer is defenceless against it. A brief vignette, stripped of narrative, devoid of explanation, it bypasses the rational parts of our brain and pierces to that deeper, more primitive part where instinct and fear reside with buried memories of primeval experience. It’s been a few weeks since I saw it, but I’m still deeply aware every night as I turn out the lights of all the shadows around me in my apartment and I can’t help feeling tense and uneasy as I try to get to sleep. In fact, I almost wish Steve hadn’t shown it to me … and yet it does exactly what I want from a horror film and so rarely get.

Watch it at your own risk!

Comments