The pleasures of hand-made animation

When we watch movies, lost in story, we aren’t aware of the fundamental fact that there really is no actual movement in what we see. Movies (and video) consist of sequential streams of still images which our brains translate into an impression of movement. Very quickly following the invention of cinema, this fact was seized on by people who realized that a semblance of life could be given to inanimate objects. (Actually, to be more accurate, this process predated the invention of movies and in fact inspired that invention – flipbooks and zoetropes showed that this illusion of movement could be evoked from still images.) Animation is as old as the movies themselves. And while computers have facilitated the elaboration of the process, and turned animation into one of the most profitable categories of entertainment, I have to admit that my preference is still for the “hand-crafted”, that intense, laborious process by which individual artists, alone or in collaboration, painstakingly create the illusion frame by frame in whatever medium they choose – paper, clay, puppets …

While computers are today almost inevitably used to enhance even these efforts, the artisanal quality still shines through, whether in the hand-drawn art of Miyazaki or the elaborate mechanical inventions of Graham Annable and Anthony Stacchi’s The Boxtrolls. The great thing about the varieties of traditional animation is that stylistic options are virtually unlimited, from the remarkable cut-out silhouettes of Lotte Reiniger to the warmly tactile claymation of Nick Park and Aardman Studios. Artists have animated with sand, with oil paints, even with meat. Disney opted for a sanitized storybook approach, while the Quay Brothers drew inspiration from ominous Eastern European art and literature. Look at the differences between Disney’s and Jan Svankmajer’s adaptations of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland … the source might have been the same, but the results are worlds apart.

In the realm of drawn animation, few if any filmmakers have ever equaled the work of Hayao Miyazaki which combines delicate character detail with epic visual and narrative sweep. As I wrote here a year ago, I had come away from Miyazaki’s final film, The Wind Rises (2013), with ambiguous feelings. And as I also mentioned, I have always reserved final judgment of his work for when I can see it with the original Japanese soundtrack – no matter how carefully the English dubbing is done, separating the images from their original language creates a sense of disconnection, at its worst undermining the effect of the visuals (the worst instance of this is the jarring voice of Billy Bob Thornton as the sinister monk in Princess Mononoke which completely pushes you out of the film’s carefully constructed world).

Having recently watched The Wind Rises on Blu-ray, I found the film coming into sharper focus, its subtle narrative layering more clearly visible. There were complaints at the time of the film’s release that it was unacceptable to paint a sympathetic portrait of the man who designed the deadliest fighter plane of World War 2, the Mitsubishi Zero (I wondered at the time whether those complaining would also object to a sympathetic portrait of those who designed, say, the Spitfire or the P57 Mustang, elegant machines which were also created with the sole intention of killing). In Miyazaki’s film there’s a continual tension between the dreams of Jiro Horikoshi and the consequences of his efforts to realize those dreams. The sense of freedom evoked by flight has been a running theme in much of Miyazaki’s work, but he has never shied away from the darker purposes to which the machines that enable us to rise above the earth have been put.

Crucial to The Wind Rises is the parallel narrative of Jiro’s relationship with Naoko Satomi, a young woman struggling with tuberculosis. Throughout the film, hopes and dreams are overshadowed by death and a deep sense of impending loss. The Wind Rises is a melancholy tragedy, a contemplation of how the best in a person bears the seeds of its own destruction. As is usual with Miyazaki, this is all presented in stunning visual terms and leavened with notes of humour.

*

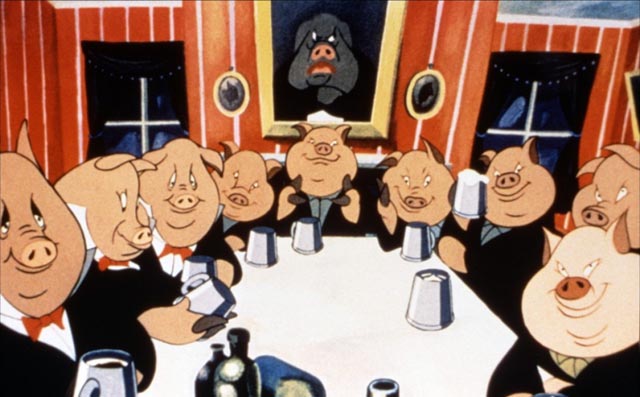

I recently saw John Halas and Joy Batchelor’s adaptation of George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1954) for the first time, thanks to Network’s Region B Blu-ray. This, the first British animated feature, was made at a time when Disney had firmly established in the public’s mind what animation should be – that is, colourful films for kids laced with musical numbers. Halas and Batchelor’s film, on the other hand, was dark and ominous and embodied sophisticated political ideas; these were not your typical talking animals.

For the most part the film adheres very closely to its source, Orwell’s fable about the course of communist revolution as played out on a small English farm; suffering at the hands of a harsh master, the animals band together to kick him out and start running their society by themselves. It doesn’t take long for factions to form and the idea of equality becomes corrupted as the pigs, smartest of the animals, find ways to increase their privileges at the expense of the “less equal” animals. By the end, chillingly, the pigs have become indistinguishable from their erstwhile human master. This is, of course, the final note of the book. Commercial considerations, however, made the producers fear that it was too much of a downer and would put people off, so in the film an extra beat is added as the other animals band together again and drive out the pigs … which is really not a solution at all, as we’ve just seen what no doubt will happen all over again. The idea that the revolution can be saved by kicking out the bad apples doesn’t hold up historically (it’s more likely that the bad apples will repeatedly consolidate their power by crushing any signs of opposition, as Stalin did in the ’30s and Mao in the ’60s and ’70s).

But apart from the compromised ending, Animal Farm is beautifully produced, the artwork expressive and colourful, with Maurice Denham providing the voices for all the animals. If anything dates it, it’s the narration spoken by Gordon Heath, which makes it seem too much like a dutiful rendering of a classic.

*

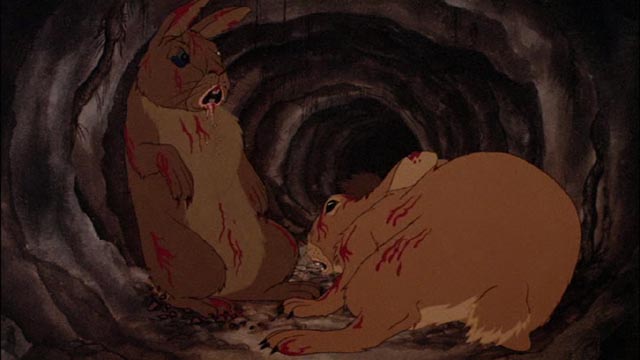

Although there are no direct connections between Animal Farm and Watership Down (1978), there are undeniable similarities between these two British films. While Richard Adams’ novel is more epic fantasy than political allegory, there are nonetheless allegorical elements in its story of a small band of rabbits seeking a new life away from a repressive society. The book was a huge popular success when it attracted the attention of agent and occasional producer Martin Rosen. Rosen became determined to turn the book into a movie even though he had no experience with animation, initially hiring John Hubley, perhaps best known for his surrealistic work for UPA in the ’50s, to direct from Rosen’s own script. But a combination of “creative differences” and Hubley’s declining health pushed Rosen to take over as director.

Like Animal Farm, Watership Down is deeply rooted in a pastoral vision of England, its hand-drawn imagery creating a genuine tension between a genteel watercolour landscape and an at times surprisingly violent view of life. The story centres on two young friends, the runty, ridiculed Fiver (voiced by Richard Briers) and Hazel (John Hurt); Fiver is a rather ethereal character given to fits during which he has visions – and one day he has a vision of the rabbit warren’s land disappearing under a flood of blood. Although the rabbits have no way of knowing, we can see the billboard announcing a new housing development, portending the destruction of their field.

Unable to convince the old, entrenched rulers of the band, the pair manage to persuade a number of the younger rabbits to leave, an act of rebellion which brings on pursuit by the the warren’s enforcers. The story follows the group’s trek across country, faced by various dangers which include predators (a badger, a dog, an owl, a farm cat … and various humans) as well as another warren with distinctly fascist tendencies. Before they find their final safe haven on Watership Down, there are moments of danger and death – including a genuinely horrific account of the destruction of the original warren with its inhabitants crushed and buried by construction equipment.

Although on paper the idea of an animated film about the adventures of bunnies sounds very Disneyesque, Watership Down is much more mature than it at first appears, a contemplation of life as something fraught with danger which will inevitably end in death … with meaning rooted in what the individual makes of existence from moment to moment while it lasts. It was probably this darkness that caused the film, despite its obvious qualities and its origins in a best-selling book, difficulties in getting as wide a distribution as it deserved. No doubt quite a few young children were traumatized by seeing it.

I’m not sure whether the new Blu-ray release of Rosen’s film is a sign of anything larger stirring at the Criterion Collection. This is just the second animated feature the company has released (unless you go back to 1993 and their laserdisk of Akira). The company has been taken to task repeatedly for their lack of attention to this significant strand of film history, with last year’s release of The Fantastic Mr Fox having more to do with Wes Anderson than the genre. This edition of Watership Down is a promising sign, but in many ways it’s a fairly conventional choice and the film has been readily available on disk before. When you compare the BFI’s proven commitment to the form with their extensive list of releases by the Brothers Quay, Jan Svankmajer, Lotte Reiniger, Phil Mulloy and others, it’s clear that there’s a large gap waiting to be filled by Criterion. Hopefully, Watership Down is just the start of the company’s expansion into this neglected area.

The disk itself provides several supplements which serve to highlight what separates Rosen’s film from typical children’s animated features, including an interview with Rosen himself, a piece by Guillermo Del Toro, picture-in-picture storyboards and a featurette on the stylistic choices made by Rosen and his animators.

*

Perhaps Criterion could consider forming a relationship with the Museum Karla Zemana in Prague to make available a hi-def collection of the films of the great Czech director Karel Zeman. The two latest releases from the Muzeum illustrate the range of Zeman’s approaches to animation and effects filmmaking. The Tale of John and Mary (1980), Zeman’s final feature – an original story rooted in Czech folktales – is about John, an adventurous young man who goes out into the world to seek his fortune. He’s accompanied by three impish figures who try to influence his decisions for good or ill, and falls in love with Mary, a nymph. Each of them makes a deal to enable them to join the other in their world, creating new obstacles before they finally manage to come together.

The storybook style, reminiscent of the earlier Krabat, combines drawn settings which have a pronounced two-dimensional quality with articulated cut-out figures. The playful storybook visual qualities belie some of the darker elements in the narrative, aligning this more with traditional fairytales than the more sanitized versions of Disney.

On the Comet (1970) was the third of Zeman’s Jules Verne adaptations, after The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958) and The Stolen Airship (1967), and has a more pointed political purpose than those earlier adventures. In a North African country, various European garrisons face off against each other. A passing comet tears away part of the Earth’s surface and sucks it up to carry off into space. The various inhabitants gradually come to the realization that, separated from their former national interests, there’s no longer any reason to fight wars with each other. But then the comet’s orbit brings them back close enough to Earth for them to escape back to the home planet, where their stupid national rivalries are reactivated.

As in his other live-action films, Zeman uses a variety of techniques here, with elaborate matte shots combining drawn backgrounds and live action, and his signature stop motion (there are dinosaurs on the comet). Throughout his career Zeman remained a uniquely imaginative fantasist whose work gains significant charm from the “hand-made” qualities of his image-making. On the Comet was the sixth and last of his features to combine animation and live-action.

*

At the far end of the spectrum from Zeman, Annable and Stacchi’s The Boxtrolls (2014) is a stop-motion feature which uses all the technical resources available to the filmmakers to create a vivid, three-dimensional world complete with dozens of characters, elaborately complex machines, and a setting which is as detailed as a real city with its winding streets and looming buildings. Like the previous two features from Laika Entertainment, Henry Selick’s Coraline and Chris Butler and Sam Fell’s Paranorman, The Boxtrolls has a darker edge than the usual kids’ film, addressing fears of abandonment and death from a child’s point of view.

Eggs (voiced by Isaac Hempstead Wright) is a boy raised by the titular trolls, scavengers who live deep beneath the city, emerging at night to steal discarded objects. The people in charge of the city see them as thieves and vermin and the sinister Archibald Snatcher (Ben Kingsley) has taken on the job of exterminating them in hopes that he can win a place in high society – although the snobbish and effete rulers, led by Lord Portley-Rind (Jared Harris), have no intention of opening their tight little world to the unworthy Snatcher. When Eggs encounters Portley-Rind’s rebellious daughter Winnie (Elle Fanning), they become instrumental in bringing the two worlds together, exposing the nasty schemes of Snatcher which have maligned the essentially harmless trolls, and transforming the atrophied society of the town.

The film is packed with visual invention, comic character detail (Snatcher’s trio of minions, Mr Trout [Nick Frost], Mr Pickles [Richard Ayoade] and Mr Gristle [Tracy Morgan] are stand-outs), and a message of understanding and inclusion which is handled lightly without hammering the point. But most importantly, it’s a visual treat which illustrates just how much can be achieved by talented craftspeople working one frame at a time.

Comments