Viewing notes, March-April 2015: part two

Falling behind again, so here I’ll just sketch in some impressions of movies I’ve been watching (and the disks they came on). If I had the free time, I could be posting here pretty much every day as the longer I write this blog, the more I feel I have to say about what I’m watching (not that I could possibly expect anyone to keep up with that kind of output). And so what follows doesn’t reflect everything I’ve seen recently, nor do these comments do anything like full justice to some of these films; I’d just like at least to acknowledge them.

A Touch of Sin (Jia Zhangke, 2013)

The latest feature from one of the most incisive filmmakers working in China today, A Touch of Sin presents four coolly observed narratives about the ways in which political and economic circumstances in China push otherwise ordinary people to extreme acts of violence. Jia’s work has always hovered between documentary and closely observed social narratives, evoking the forces which constrain and not infrequently crush the individual; in this new film, it’s as if the unbearable pressures which have been building beneath the surface of his work have finally erupted. The film begins on a jarring note with a seemingly inexplicable act of violence cast in the form of movie tropes familiar from the western; but after this, a stark signal of those subterranean forces, Jia settles down to the kind of careful observation of social forces and their intersection with personal psychology, each narrative line leading logically and inexorably to yet another explosion of violence. Jia’s full body of work provides one of the clearest expressions available for an outsider of what life is like inside the vast unwieldy edifice of modern China. It seems remarkable that he’s been able to keep on making these films in a cinematic environment which has largely been given over to self-aggrandizing historical epics and martial arts fantasies. (Kino Lorber Blu-ray, no supplements)

*

Neighboring Sounds (Kleber Mendonça Filho, 2012)

The first feature of Brazilian film critic Kleber Mendonça Filho shares a few characteristics with Jia’s work – the use of long takes and a seemingly detached view of social conditions and their reflection in individual behaviour. Not surprisingly, given his background as a critic, Mendonça Filho adds referential layers which summon memories of other films and genre tropes to his depiction of life on a single street in Recife (in fact, the street where the director himself has been a long-time resident). This long film lacks a clear narrative line, following a number of characters who pursue their own lives and occasionally interact with or impinge on each other, and yet it has a distinctive, almost hypnotic, attraction which draws the viewer in and holds attention with a masterful assurance. The characters vary in terms of social class, but the street is dominated by one particular family. There are small tensions and irritations, the inevitable friction which arises when people are forced to live in close proximity, and a sense of fear suggested initially by a minor theft from a parked car but more deeply embedded in the repeated images of security gates, barred windows, and occasional glimpses from highrise balconies of a nearby favela separated from the street by high concrete walls. What plot there is is set in motion by the arrival of a few men offering to provide security for the street. Mendonça Filho subtly hints that there may be more to these men than the simple economic transaction they make with the residents (perhaps the car break-in was coincidental, but the viewer may suspect that this “security” is actually a protection racket). Ultimately, this core thread comes to a head in the film’s final scene where we learn something which goes back two decades and illuminates (without ever being entirely specific) something about class conflicts simmering beneath the surface of Brazilian society. Not surprisingly, given the film’s title, the use of offscreen sounds is elaborate and subtle, instilling much of the sense of impending dread which suffuses the superficially mundane events depicted. (Cinema Guild Blu-ray, illuminating director’s commentary, deleted scenes, plus four short films by Mendonça Filho)

*

Dr. M (Claude Chabrol, 1990)

Although I’ve seen quite a few of Claude Chabrol’s films, going back to his key contributions to the New Wave in the late ’50s, I had actually never heard of this odd, sci-fi tinged thriller somewhat fatally made just before the fall of communism and the destruction of the Berlin Wall. That particular symbol of division and the conflicts it represented between two seemingly intractable ideological systems is key to the film’s structure and meaning – and so, set as it is in a near future, Dr. M was already out-of-date before it was released. I discovered this movie through my recent reading of David Kalat’s excellent The Strange Case of Dr. Mabuse (McFarland & Company, 2001), detailing the history of the monstrous criminal figure invented by writer Norbert Jacques in the early ’20s and given lasting pop-culture life by Fritz Lang in his two-part silent epic Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (1922), his second sound feature Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (1933) and his final film The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960). Kalat argues that, although less well known in North America, Mabuse is as complex and lasting a pop culture figure as Frankenstein, undergoing an evolution from his original role as manipulator of human weakness for his own profit into something more abstract (the original Mabuse dies, but his insidious spirit takes possession of other people, expressing the appeal of fascism which draws a variety of intelligent men into criminal and political activities which set them against the constraints of bourgeois society). Although I knew of (and have seen several of) the low-budget thrillers featuring Mabuse produced by Artur Brauner through the ’60s (in which he becomes a kind of Bond villain bent on world domination), Kalat introduced me to several films I had either never previously come across or hadn’t associated with the character. I’m still not entirely convinced that Gordon Hessler’s Scream and Scream Again (1970) really belongs to this series, but the title of Chabrol’s film declares its connection unequivocally. Here, Mabuse is a media mogul kept alive by various medical machines who sells the ultimate consumer good to a nihilistic culture: self-destruction. The city is plagued by spectacular suicides which initially appear to be terrorist acts. Shot somewhat awkwardly in English, Dr. M remains too abstract to work fully as a thriller, but Chabrol does manage to create an interesting atmosphere of doom overhanging a morally bankrupt capitalist society. Interestingly, both its successes and failures as drama are reminiscent of fellow New Waver Francois Truffaut’s English-language sci-fi parable Fahrenheit 451. In Chabrol’s filmography, it probably most closely resembles his more successful nihilist thriller Nada (1974), about a gang of leftist revolutionaries who kidnap an American ambassador. Not surprisingly, this commercial failure has remained obscure despite Chabrol’s high profile; I’m grateful to a friend who managed to track down a copy on-line for me. (Low quality download converted from VHS tape)

*

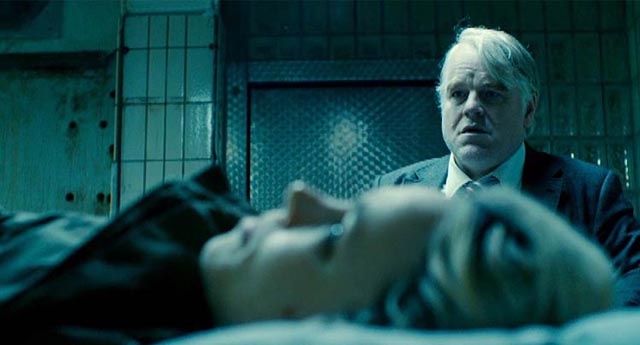

A Most Wanted Man (Anton Corbijn, 2014)

As in his previous feature The American (2010), Anton Corbijn gives this John Le Carre adaptation a coolly detached tone which seems intent on evoking European thrillers from the ’60s and ’70s. And like The American, this film ultimately seems too enervated to evoke much emotional involvement from the viewer. The elaborate plot involves a schlubby German intelligence agent who seems tired of rigid ideological attitudes and, unlike his superiors and the American agents hovering around the fringes of the story, his empathy for those he is tasked with spying on (specifically a Chechen refugee who may or may not be in Hamburg to set up some terrorist action) seems to offer an alternative way of looking at and dealing with political conflicts. Being a Le Carre story, that sensitivity will inevitably lead to personal crisis; but the schematic nature of the script by Andrew Bovell makes the bleak ending seem both inevitable and overly contrived. The film perhaps got some of its favourable critical attention because it has Philip Seymour Hoffman in his final role. The combination of a fake German accent and the mannered weariness of the character merely reinforced, for me at least, the feeling of detachment created by Corbijn’s approach to the material. (e one Blu-ray, with two short featurettes: a making-of and an interview with Le Carre)

*

Harper (Jack Smight, 1966)

Adapted by William Goldman from the first of Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer novels and directed by journeyman Jack Smight, Harper was a mid-’60s attempt to recapture the flavour of the classic Bogart-style detective movie (right down to including Lauren Bacall in the cast). Paul Newman gives a relaxed performance as the renamed detective (reputedly the name change was made so the title could begin with an “H”, which Newman considered lucky – Hud, The Hustler, Hombre). The convoluted story begins with the disappearance of a rich man, who may have been kidnapped. As Harper digs into the man’s background, it turns out that he was an unpleasant and abusive drunk, whom nobody liked, including the wife who’s hired the detective. Several different storylines revolve around the central thread and Harper manages to get himself beaten up a few times before untangling it all with a cynical lack of happy endings for anybody. The cast is very good, Conrad Hall’s cinematography colourful (though all the process shots of Harper driving around in his battered convertible look painfully dated now), but the film seems to ramble somewhat aimlessly through its lengthy running time, though not in the meaningful way Robert Altman achieved seven years later in The Long Goodbye. As Goldman points out in his occasionally cranky, somewhat repetitive and wildly discursive commentary (the tone will be familiar to anyone who has read his books about Hollywood), the heyday of the detective film was long over by 1966 (Robert Aldrich had all but nailed the coffin shut with Kiss Me Deadly in 1955); the genre had been incredibly vibrant and prolific in the ’30s and ’40s, but by the late ’50s and early ’60s it had been taken over by television. Harper was a surprising success because nothing quite like it had been seen on the big screen for years, but despite the impressive cast, it now looks very much more like those TV shows than like the classic noirs. For all its virtues, it seems rather ordinary, lacking either the lasting impact of the great detective films or a self-conscious critique of the genre; that double feat would have to wait eight more years until Robert Towne, Roman Polanski and Jack Nicholson could restore the detective to his mythic, existential place in popular culture with Chinatown. Seen now, Harper is a minor, occasionally entertaining potboiler. (Warner Video DVD, with Goldman commentary and brief TCM introduction by Robert Osborne)

*

Interstellar (Christopher Nolan, 2014)

I’m not a fan of much of Christopher Nolan’s work – apart from Memento and The Prestige, I tend to find his movies ponderous and overly self-serious. So everything I heard and read about Interstellar put me off going to see it in the theatre. However, for some reason I was tempted to take a look when it was released on disk and much to my surprise, I quite liked it. Yes, it has his usual ponderousness and there are a lot of ridiculous things in it, but it does manage to create an interesting sci-fi world with a pleasing solidity provided by his use of actual physical sets and effects rather than wallowing in CGI – something that’s always guaranteed to appeal to me. I quite liked the elaboration of the narrative’s various time paradoxes and the production team’s approach to design. Its chief weakness for me was the central absurdity, given the virtually infinite possibilities of other worlds available in the universe, of having our hero and his team directed to three extremely unstable worlds located close to a black hole. This makes for the kind of overwrought drama Nolan seems to be attracted to, but fails in terms of story logic. (Paramount dual-edition Blu-ray/DVD combo, with multiple documentary featurettes)

*

Moonrise Kingdom (Wes Anderson, 2012)

I had gone off Wes Anderson by the time Moonrise Kingdom was released. I really like his first three features, but he seemed to go off the rails with The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), in which the light, fabulist sensibility of the earlier films congealed into something unappealing. In that instance, the criticism frequently levelled against him of being overly fey seemed justified. Subsequent criticism of The Darjeeling Limited (2007) seemed to confirm that whatever had given charm to Bottle Rocket, Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums had devolved into self-parody. That said, his next film, The Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), was his best to date and remains my favourite. By all reports Moonrise Kingdom was yet more self-parody, but having recently seen and liked The Grand Budapest Hotel, I decided to give it a try. Yes, it leans heavily on his delicate storybook approach (the characters virtually live in a doll’s house), but at its centre are two really engaging characters – the adolescent outsiders Sam (Jared Gilman) and Suzy (Kara Hayward) – who decide to walk away from a society which views them both as ridiculous and valid targets of group contempt. Their disappearance on a small New England island triggers changes in the attitudes of the people involved in searching for them, a collection of comic types who manage to recapture the charm which made the earlier films so likeable. (e one dual-edition Blu-ray/DVD combo, with three brief, throw-away featurettes)

*

The East (Zal Batmanglij, 2013)

The East, like Sound of My Voice (2011), co-writer and director Zal Batmanglij’s previous collaboration with co-writer and star Brit Marling, is the story of a skeptical investigator infiltrating a secretive organization and gradually finding herself implicated in the actions she is supposed to be exposing. In The East, Marling plays Sarah, an employee of a private security company intent on making money off corporations who have been targeted by an eco-terror group who attack executives with the things which those corporations have inflicted on others – pollution, toxic drugs which do more harm than good, and so on. Although Sarah is tasked with exposing and preventing these attacks, she gradually comes to identify with the group’s aims because the things they are trying to expose are vitally important. What begins as a simple technical task becomes increasingly morally complex. Batmanglij and Marling make an excellent team, with both these features exhibiting a nuanced approach to very real issues. (Fox Searchlight Blu-ray, with six behind-the-scenes featurettes and several deleted scenes)

*

Only Lovers Left Alive (Jim Jarmusch, 2013)

I’ve been a big fan of Jim Jarmusch’s work since I first saw, and fell in love with, Stranger Than Paradise (1984 – wow, that’s more than thirty years ago!). I missed his second-last feature, The Limits of Control (2009), which didn’t seem to get much of a release despite the modest success of Broken Flowers (2005). His latest film did play briefly in Winnipeg and I really wanted to see it, but somehow didn’t manage to get around to it before it vanished. Only Lovers Left Alive is Jarmusch’s version of a vampire film – that is, it avoids the cliches of the genre and focuses on the implications of immortality. The film’s trio of blood drinkers, Adam (Tom Hiddleston), Eve (Tilda Swinton) and Marlowe (John Hurt) have to deal with boredom and living in isolation from the rather pathetically limited human society around them. Adam spends his time creating music which continually seems to get stolen; Eve lives a dissolute life in North Africa where she gets her supply of safe blood from Marlowe (yes, Christopher Marlowe the 16th Century writer, confirmed here as the true author of Shakespeare’s plays). Eve is called to the States by Adam, where they can resume their centuries-old romance. To represent the dull human world from which they are separated, Jarmusch shot much of the film in Detroit, a semi-derelict city recently used to very good effect by David Robert Mitchell as the setting for It Follows. Here, the lives of Adam and Eve are disrupted by the arrival of Eve’s sister Ava (Mia Wasikowska), a careless hedonist who doesn’t practice their restrained form of vampirism (Adam buys his supply from a local doctor); Ava prefers to drink fresh from an attractive man’s throat, thus exposing Adam and Eve to potential interest from the authorities. Returning together to North Africa, they discover Marlowe dying from drinking tainted blood … not so immortal after all. Jarmusch’s vampires are aesthetes struggling to suppress their animal side through refined cultural pursuits, but in the end they come to accept the full implications of their condition. Only Lovers Left Alive would make an interesting double-bill with Neil Jordan’s Byzantium as a concerted assault on the decline of the vampire into a (excuse me) bloodless figure of teen romance. (Sony Pictures Classics Blu-ray, with a 50-minute behind-the-scenes doc and almost half-an-hour of deleted/alternate scenes)

*

Seconds (John Frankenheimer, 1966)

I’m not sure why it took me so long to get around to watching Criterion’s Blu-ray edition of my favourite John Frankenheimer film, but I finally did a few weeks ago and the film holds up very well. Frankenheimer was one of the most talented directors to come out of the golden age of live television and he always brought an impressive technical facility to his film work even when the actual content was perhaps not entirely worth the effort. (Films like Grand Prix [1966] and The Gypsy Moths [1969] were famously made because he was interested in certain technical problems – how to give an audience an immediate, visceral experience of formula one racing and skydiving, respectively.) Seconds capped a remarkable five-film run in the early ’60s, beginning with Birdman of Alcatraz, followed by The Manchurian Candidate, Seven Days in May and The Train, before getting to this, perhaps his most emotionally resonant movie. The concept is simple: a bored, emotionally dead middle-aged man is introduced to a secret corporation which can completely remake him and give him a new life – extensive plastic surgery and rigorous physical training make him “young” again and he starts over as an “artist” on the West Coast. The problem is, he’s the same guy inside, only now he’s been detached from his familiar existence, the boring job, the stultifying marriage. The corporation can only remake the exterior; he’s stuck with himself on the inside. Meeting a free-spirited woman briefly opens up new possibilities, but it’s not enough. He suffers a breakdown which threatens to expose not only the corporation, but also all his neighbours in the beach colony who, like him, have been “renewed”. Expressively shot by the great James Wong Howe in gorgeous black-and-white, Seconds has a standout cast which includes John Randolph, Salome Jens, Murray Hamilton, Jeff Corey and Will Geer. But the whole thing is anchored by the finest performance of Rock Hudson’s career (in retrospect, perhaps enriched by the stresses of repression and concealment in his own life as a gay man “playing” a Hollywood heartthrob for a passionate female audience). (Criterion Blu-ray, with multiple new and archival supplements about the making and significance of the film, including a Frankenheimer commentary ported over from an older DVD edition)

Comments