Criterion Blu-ray review: The Killers (1946/1964)

“The Killers”, first published in 1927, is quintessential Hemingway. Stripped of all adornment, the incident it describes has terrific impact while remaining chillingly enigmatic, implying without spelling out a bleak vision of existence. More a vignette than a short story, it is seen through the eyes of Hemingway’s recurring character Nick Adams, here a young man on the verge of heading out into the world from his small home town. One evening at Henry’s diner, where Nick is the only customer, two men come in. There is something both comical and threatening about them as they give George, the man behind the counter, a hard time about the menu. After ordering some food, the men pull guns and force Nick back into the kitchen, where he’s tied up with Sam, the black cook. The men settle down to wait for the arrival of “the Swede”, a regular customer, whom they casually mention they have come to kill as a favour to a friend.

When the Swede doesn’t show, the men eventually leave. Untied, Nick runs over to a nearby rooming house to deliver a warning. He finds the Swede lying on his bed in his dark room, seemingly overcome by inertia. He knows the men are coming for him, but he’s not going to do anything about it. All he’ll say is “I got in wrong”. His fatalism scares Nick, who, returning to the diner, says he thinks it’s time he left town. George says that’s a good idea.

“The Killers” is a gem of concision and Hemingway’s dialogue, so compressed and elliptical, seems ready-made for transformation into a script. Not surprisingly, it has been turned into a short film a number of times. It has also been turned into a feature twice.

Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946) is one of the greatest films noirs, its structure – digging into a murky past through an investigator’s encounters with a number of characters who gradually piece together a tragic story – earning it a reputation as “the Citizen Kane of noir”. But of course the story the film tells is not Hemingway’s. It had to be invented from scratch by scriptwriter Anthony Veiller (with uncredited additional work by John Huston and Richard Brooks). Taking Hemingway’s original (which forms the film’s first act in a very faithful bit of adaptation) as its starting point, the film follows the search of insurance investigator Jim Reardon (Edmond O’Brien) for an answer to why the Swede (Burt Lancaster) met his death so calmly.

Not surprisingly, the mystery revolves around a femme fatale. The Swede falls for Kitty Collins (Ava Gardner), a woman involved with gangster Big Jim Colfax (Albert Dekker), after his boxing career ends because of a hand injury. The Swede becomes a petty criminal, spends time inside, and after he gets out he’s brought into Colfax’s scheme to steal a factory payroll. The levels of betrayal which follow are thick and intricate, finally undermining everything the Swede believes about his place in the scheme of things and the ideal of romance he’s projected onto Kitty. With all his illusions stripped away, he has nothing left to live for.

The film, despite the expansion of the narrative, remains as precise and focused as Hemingway’s story, with the scriptwriters managing to emulate the author’s style of dialogue throughout. Visually, The Killers is all rich blacks, the characters’ lives obscured by shadow. The robbery itself is a bravura single crane shot, something you might expect of Orson Welles, displaying great technical prowess without calling unnecessary attention to itself. And the cast down to the smallest part is one of the finest in the genre, with Burt Lancaster assured yet vulnerable in his first role; Ava Gardner alluring but untrustworthy as Kitty; William Conrad and Charles McGraw a nightmarish comedy team as the killers; and Sam Levene, Vince Barnett, Jack Lambert, Albert Dekker and Jeff Corey adding depth and colour to the story. Edmond O’Brien provides a stable centre around which the tragedy evolves.

When producer Mark Hellinger (a key figure in film noir – They Drive By Night, High Sierra, Brute Force, The Naked City) was planning this 1946 adaptation, he initially wanted the young Don Siegel to direct, but studio contractual issues got in the way. At the time Siegel was a master montage editor with directing credits on only a couple of shorts, including the Oscar-winning Star in the Night (1945). Eighteen years after the release of Siodmak’s version, Siegel got another shot at the story. Well, at least the title is the same. The 1964 version of The Killers has virtually nothing to do with Hemingway and, in fact, is more of an adaptation of the previous film’s invented narrative.

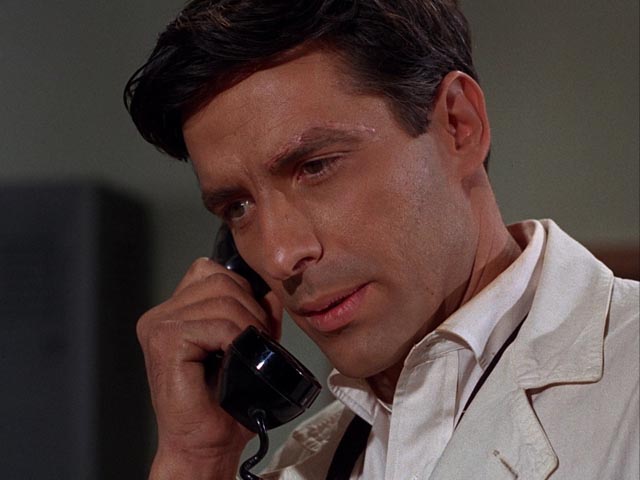

Rather than a boxer, this version centres on race car driver Johnny North (John Cassavetes), who is found by a pair of hitmen teaching auto mechanics in a school for the blind. The killers, Charlie Strom (Lee Marvin) and Lee (Clu Gulager), brazenly push their way into the school and gun Johnny down in a classroom. Despite the older Charlie’s standing advice to the younger Lee not to think about their work, Charlie becomes obsessed with finding out why Johnny just stood there, neither resisting nor trying to escape his imminent death. This question is exacerbated by the fact that the team has been paid far more than their usual fee for the job. And so they set out across the country to find out who hired them and why.

Once again, the story unfolds in flashback and it revolves around Johnny’s life as a successful driver being pulled off course by a seductive woman, Sheila Farr (Angie Dickinson). (If there’s a weakness to Gene L. Coon’s screenplay, it’s that too often the witnesses describe in detail events which they actually have no personal knowledge of.) The investigation leads to gangster Jack Browning (Ronald Reagan) and an armoured car robbery, a heist which collapses under multiple betrayals, the final one stripping Johnny of everything he believed about his relationship with Sheila. As Charlie says towards the end, the only reason a man accepts his death so calmly is because he’s already dead … just like the Swede, Johnny no longer has anything to live for.

The only real point of connection between Siegel’s film and the earlier adaptation, and the story before it, is in the mystery of a man’s passive acceptance of his own death. In tone and style, the two films are world’s apart: the romantic tragedy of the 1946 version has become a violent cynicism by 1964, with Siegel’s film looking forward to the bleak existential crime films of the late ’60s and ’70s. A key difference lies in the radical change in protagonists, from O’Brien’s insurance investigator to the pair of killers. Siodmak’s film, through Reardon (and Police Lieutenant Sam Lubinsky [Sam Levene]), stands somewhat apart from the typical noir, providing a stable world from which to observe the Swede’s descent into darkness – in effect, the film is an auto-critique of the genre, observing the doomed hero’s torment from outside; in Siegel’s film there is no stable world, everyone is corrupt, everyone dies and there isn’t a trace of romantic tragedy to offset the air of doom.

While The Killers ’46 is rich in shades of darkness, The Killers ’64 is garishly shot in sunlight and overlit rooms. In practical terms, this is because the film was originally made for television, a medium which at the time was at the mercy of small screens which needed that brightness to make the image readable in people’s living rooms. But what was dictated by necessity became an aesthetic effect: there are no shadows in this world, nowhere for nuance to reside. In the bright glare, the viciousness of the characters is fully exposed – this is an ugly, violent world where genuine emotional connections are impossible.

The film’s TV origins result in some weaknesses – it was shot quickly and cheaply, its many process shots glaringly obvious in hi-def, giving it a crude look. But the cast is excellent, with Marvin and Gulager’s pair of killers hugely influential (Quentin Tarantino virtually built his career on their image) – this is one of Marvin’s finest performances, and Gulager plays off him with chilling comic brilliance; Angie Dickinson was never more attractive, maintaining a balance between cold calculation and seductive, untrustworthy emotional warmth; John Cassavetes has his usual presence in a job-for-hire performance; Claude Akins as Johnny’s partner and mechanic Earl gives the film’s most authentically emotional performance; and Ronald Reagan, in his final film role (and first as a villain) is icily effective as Jack Browning, a role he despised (he took the part as a favour to his pal, Universal Studios head Lew Wasserman).

The pairing of both versions of The Killers in Criterion’s new Blu-ray edition (an upgrade from their 2003 DVD) provides a fascinating look at how a single narrative idea can appear in radically different form in different periods. The 1946 version evokes the bleak sense of loss prominent in the early post-war years, while the 1964 version looks forward to a world collapsing into hopelessness and disorder. In fact, Siegel’s film was perhaps a little ahead of its time. Commissioned for television, it was deemed to be too violent for broadcast (JFK was assassinated during production) and Universal ultimately gave it a theatrical release to recoup costs.

As in the earlier DVD edition, Criterion have included a 1956 adaptation of the story. This was codirected by 24-year-old Andrei Tarkovsky, with Aleksandr Gordon and Marika Beiku, at film school in Moscow. This 20-minute short is the most faithful of the three versions, directly transcribing the story’s events and using Hemingway’s dialogue virtually word-for-word – including the repetitive references to Sam the cook as “nigger” (the story’s implicit racism is avoided in Siodmak’s film and, of course, the entire diner scene is absent from Siegel’s). It’s interesting to imagine how Hemingway’s story might have been seen by the Russians, with its hopelessness, violence and racism, as an accurate portrait of American society.

The disk

Criterion’s upgrade of these two films is a big improvement over the original edition. The 1.33:1 transfer of the 1946 version, made from a fine-grain 35mm master, is absolutely gorgeous, with rich blacks and contrast which finds a high level of detail in shadow. The 1964 version, made from a 35mm interpositive, reveals all the bright gaudiness of the garish production design, as well as the technical shortcomings of the extensive process work; it’s even possible to see shadows on the backdrop outside the window of Jack Browning’s office. Criterion have chosen to present the film in an open matte 1.33:1 transfer, which may be technically correct (this is how it would have been seen if presented as originally intended on television), but Siegel and cinematographer Richard L. Rawlings had framed the images to work in both that format and also in 1.85:1 for theatrical screenings. The full frame image is less effective than the more pleasing wider version (as can be seen in the region B Blu-ray from Arrow Video which includes both versions); the film seems stronger and more focused when zoomed in on a wide-screen television to crop the extra head and foot room.

The supplements

The Blu-ray ports over all the video and most of the audio extras from the DVD edition, but all the text and image galleries included in the earlier edition have been dropped, as well as isolated music and effects tracks for both features. Missing are production and publicity stills, press books and advertising materials, memos and production documentation, and Paul Schrader’s seminal 1972 essay “Notes on film noir”.

In addition to the Russian student film version (20:38), supplements include a reading of the complete Hemingway story by actor Stacy Keach (17:43); a Screen Directors’ Playhouse radio adaptation from 1949 (29:41), which is introduced by Robert Siodmak and stars Lancaster and Shelley Winters (in the Ava Gardner role); an interview with critic Stuart M. Kaminsky (17:46) about both adaptations and their relationship to the original story; an interview with actor Clu Gulager (18:46), who reminisces quite emotionally about the Siegel production and working with Marvin, Akins, Reagan and Dickinson; and actor/director Hampton Fancher reads excerpts from Don Siegel’s autobiography about the making of the film (19:32). Finally, there’s a collection of five trailers for Robert Siodmak features, including The Killers (10:18), and a trailer for the Siegel version (2:23).

The original booklet essays by Jonatham Lethem (1946) and Geoffrey O’Brien (1964) are also included.

Comments