Five Shades of B

While it’s true that I don’t – and never will – have enough time to see every worthwhile, important, artistically significant and accomplished film that becomes available on disk (let alone every one that’s ever been made), I nonetheless still spend an inordinate amount of time watching less worthy movies. I can’t help it. I have a great deal of affection for B-movies. I use the term not in a strict technical sense, but rather in the commonly accepted sense of movies which adhere to the rules of various genres; whether they cling to or attempt to bend those rules, they are absolutely shaped by them. Looked at this way, the term B-movie can be applied to cheap studio programmers, low-budget independents, even to more expensive mainstream releases which use those familiar formulas to attract gullible fans.

And so, here are a handful which I’ve recently watched with varying degrees of pleasure – arranged chronologically, rather than ranked by perceived value … though by coincidence, the last is also the best, and certainly unlike some of the others is in no sense a “time-waster”:

She Devil (Kurt Neumann, 1957)

Kurt Neumann was a journeyman director whose career went back to the beginnings of the sound era. He made westerns, Tarzan movies, comedies and mysteries. But today he’s probably best-known for several sci-fi and horror movies he directed (and occasionally co-wrote) in the ’50s, beginning with Rocketship X-M (1950), which may be one of those cases where a quick attempt to cash-in actually got into theatres before the movie it was imitating (Rocketship X-M premiered a month before George Pal’s more prestigious Destination Moon). Unquestionably, Neumann’s best-known film is the original The Fly (1958), but the year before that he made a pair of interesting if lesser-known movies: Kronos, which has one of the most abstract “monsters” of the period, a gigantic alien machine which is sucking up all energy on Earth for some nebulous alien reason (it would make an excellent co-feature with John Sherwood’s terrific, equally abstract The Monolith Monsters, made the same year); and She Devil, a medical-science-gone-wrong story which opens up some interesting gender issues.

She Devil, released on Blu-ray by Olive Films (as usual bare-bones and unrestored), begins with a fairly standard set-up – a brilliant doctor working alone in his lab has isolated a serum which may be a universal cure for all illnesses. This is derived from his experiments with fruit flies, which are the most adaptable (and mutatable) of all creatures. Having cured a variety of sick and injured animals, he feels he’s ready for a human trial. But his friend and mentor, an older doctor, feels this would be unethical … unless they can find a completely hopeless case with no possibility of survival, who would willingly consent to the treatment.

By fortunate coincidence, a patient in the older doctor’s hospital is dying of tuberculosis which has progressed too far to be treatable by any normal methods. The young woman signs a release on her deathbed, gets the shot, and very quickly regains health and strength. What the doctors are initially unaware of is that the serum has also stripped her of any social restraints. She attacks a wealthy man in front of other people, takes his money, then completely changes her appearance by using her newfound ability to will metamorphosis; with a change of hair colour and better makeup, she fools the witnesses and makes a safe getaway.

She moves into the doctors’ house, where they can observe her progress, and the younger man falls helplessly in love with her, even as the older man begins to suspect that something is wrong. With her insect abilities, stripped of moral constraints, she commits murder, seduces a wealthy man, kills him shortly after their wedding, and shows no sign of conscience. And even then, the younger doctor can’t help being smitten. But under the older doctor’s influence, he contrives a way to restore her “moral balance” with an operation on her pituitary gland. Unfortunately, this ends up reversing the cure and she finally dies, as she was meant to all along, from her incurable tuberculosis.

The standard “meddling with things man wasn’t meant to” plays out as it does in any number of such movies. What makes She Devil interesting is the particular form this theme is given, because what comes through clearly is the risk to social order posed by a strong, independent, self-willed and sexually potent woman. Men are helpless to defend themselves against her (the insect connection raises the possibility that she’s exuding pheromones which cloud their power of judgement). Only the older doctor – a man past his sexual prime? – is immune. The chilling conclusion implies that a woman needs to be submissive to the point of death in order not to distract men from the business of being in charge.

Although She Devil is visually quite bland, despite the widescreen black-and-white photography, and the cast largely undistinguished, its theme is at least partially undermined by the presence of Mari Blanchard as the title monster, an actress with very distinctive, even exotic looks, who exudes a cool sexuality which adds conviction to the character’s power to overwhelm the male intellect. She has far more vitality than any of the men can muster and by implication calls into question the status quo which the movie strains to restore by first trying to contain her, and finally by destroying her.

*

Manos: The Hands of Fate (Harold P. Warren, 1966)

The competence of a journeyman like Kurt Neumann is nowhere apparent in junk-movie favourite Manos: The Hands of Fate, a genuine oddity made famous by being featured in a popular episode of the obnoxiously smug Mystery Science Theater 3000. Over the years, I’ve seen my share of movies made by people who really didn’t know what they were doing (including a few “classics” turned out by would-be auteurs at the Winnipeg Film Group when I was involved with the co-op from the late ’80s through the ’90s, particularly the legendary Blown Ice). Sometimes that inexperience can produce interestingly unexpected results; more often than not the results are merely head-scratchingly baffling. Most people who really want to make a movie do so because they’ve seen other movies and liked what they saw, so why is it that someone who feels compelled to make their own can somehow miss the most basic principles of filmmaking?

Made for virtually nothing, shot on 16mm reversal stock in and around El Paso, cast with community theatre actors (at best) and non-actors, Manos can’t muster even a bare minimum of competence. Going by the evidence of flash frames and obvious reel ends, it appears that every inch of film which was shot was included in the cut – an impression more or less confirmed by a comment in the half-hour making-of featurette included on Synapse’s Blu-ray that it was “edited in four hours”. The camera holds on static shots with no one doing or saying anything; there are long gaps between one line and the next, emphasizing that the actors were not actually responding to each other; there are interminable montages of desert scenery as a vacationing family – dad, mom and young daughter – get lost looking for the lodge they’re booked into.

And yet, even amidst all this incompetence, a few interesting things do manage to surface – and these, of course, are what have saved the movie from the obscurity it deserves. First, there’s the bizarre character Torgo (John Reynolds), whose oddly disconnected performance is attributed in the making-of to his being stoned throughout the shoot. His strangely deformed legs apparently arose from something in the script which was dropped during production: he was initially supposed to by a satyr with hooved feet (which would explain his sexual urges towards the mom). The Master (Tom Neyman), whom Torgo reluctantly serves, is some kind of Satanic/immortal figure with a harem of constantly bickering wives, his striking costume reminiscent of something out of Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome.

A collection of disjointed, barely formed sequences in which characters exhibit no discernibly human behaviour, entirely post-dubbed with little regard to what the actors might have been saying on set (there are numerous moments with lip movements unaccompanied by any voice whatever), with images frequently out of focus, Manos may serve to give hope to someone with ambition but little talent. The fact that this movie has found its way to Blu-ray with a sometimes colourful (though very grainy and frequently scratched) 2K transfer indicates that anything is possible. Synapse, thanks to a crowd-funding effort, has not only restored the movie but supplemented it with an interesting making-of featurette in which Tom Neyman, his daughter Jackey (who played the little girl), and restoration producer Benjamin Solovey provide an amusing history of the production, as well as a commentary by Tom and Jackey Neyman. Although that commentary expresses a kind of bemused affection for their involvement in the movie, it doesn’t offer a great deal of detail about just how the film came about, which is a bit disappointing. While all of this may be a sign of the imminent end-times, no doubt it also proves that suckers like me are born at a rate of more than one a minute (the disk is currently ranked at #58 in Amazon’s Blu-ray horror listings). But Manos on Blu-ray is definitely a great party disk.

*

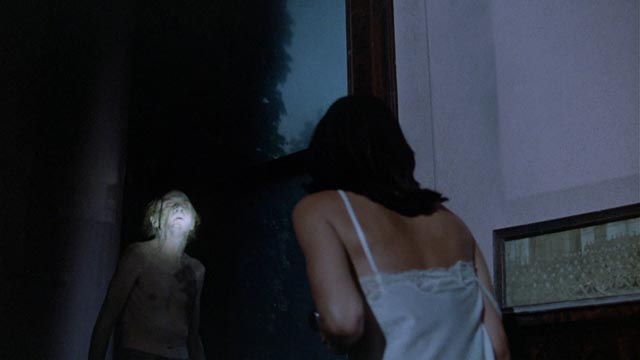

The Sentinel (Michael Winner, 1977)

Since the demise of the old studio system, B-movies are more a state of mind than a technical category, which is how it’s possible for an “all-star” movie to qualify for that designation. Michael Winner’s 1977 horror movie, a derivative riff on Rosemary’s Baby, is packed with old-time name actors in the declining years of their careers, as well as a few younger ones on the way up – Ava Gardner, Jose Ferrer, Martin Balsam, Arthur Kennedy, Eli Wallach, Burgess Meredith, John Carradine among the former; Jeff Goldblum, Chris Sarandon, Christopher Walken and Tom Berenger among the latter.

The star, however, is Cristina Raines, who mostly had a busy television career with only a handful of features thrown in. Here she plays model Alison Parker, a woman with a troubled past which apparently involved abuse from her deviant father and a couple of suicide attempts. Although she’s been in a relationship for two years with Michael Lerman (Sarandon), a shady lawyer, she’s looking for an apartment of her own because she “needs space”. In standard movie fashion, she gets a deal that’s too good to be true, with a low rent on a huge apartment in a New York brownstone which has a spectacular view of the river. The drawback is a collection of creepy fellow tenants, including a blind priest who sits all day in the window of his room on the top floor.

Alison begins to get severe migraines and has fainting spells on the job and at various parties, as her neighbours increasingly impose on her life. Needless to say, these people are not what they seem and Alison eventually discovers that she’s been chosen by sinister forces in the Catholic Church to take over from the blind priest as guardian of the gate of Hell.

Winner is best known for his crass thrillers starring Charles Bronson, but he actually started his career in England in the early ’60s with several interesting movies, the best of which, The System (1964) starring Oliver Reed, is very well made (and somewhat reminiscent of Italian films being made around the same time, particularly Valerio Zurlini’s Violent Summer [1959] and Girl With a Suitcase [1961]). By his own accounting, those early films weren’t financially successful and he made a calculated choice to move to the States and make money by directing deliberately commercial movies. The Sentinel, adapted by Winner from a novel by Jeffrey Konvitz, was a late addition to the post-Exorcist flood of demonic stories featuring almost-has-been stars.

Although hardly original, The Sentinel is competently crafted, with some effectively atmospheric touches and an air of perversion which raises it above some of its duller by-the-numbers kin. While the underlying concept is rooted in the usual Catholic nonsense about Hell and guilt (Alison is condemned to her grim fate because of those suicide attempts, which apparently are unforgivable), the expression Winner gives to the theme manages to be fairly entertaining.

Shout! Factory’s Blu-ray features three separate commentary tracks – with star Raines, author Konvitz, and the late Michael Winner himself. While Raines remains rather vague about her experiences on the movie, repeatedly hinting at unpleasantness with Winner without actually giving any specifics, Konvitz is amusing about his conflicts with the director; although he complains about Winner blowing some major moments which he considers poorly handled, he also gives the director credit for things which do work. He takes a refreshingly pragmatic view of what was done to his novel, fully aware of the studio politics involved and the commercial requirements of the marketplace.

Winner, in turn, is cheerful and quite forthright about taking the job for money, offering little in the way of respect for Konvitz, Raines and Sarandon – he prefers the old-timers in the cast. He’s also quite open about his reasons for making movies, namely getting a chance to travel to interesting places and have sex with younger women. That is, he lives up to his rather sordid reputation, while admiring his own work on the movie.

*

Christine (John Carpenter, 1983)

Although John Carpenter’s adaptation of Stephen King’s haunted car story suffers from the book’s weaknesses, it’s actually one of the director’s best-crafted movies. The chief problem is that the narrative has no real centre. The titular 1958 Plymouth Fury comes off the assembly line already, and inexplicably, evil and by the time high school nerd Arnie finds it falling apart in an overgrown yard, it has killed a number of people, including its last owner and his daughter. But Arnie sees in the wreck a machine counterpart for his own abused self. And through restoring the car, he transforms himself into a confident – eventually arrogant – stud.

Despite an interesting performance by Keith Gordon, though, Arnie isn’t the film’s protagonist; he succumbs to the seductive power of Christine and is given no way out. He gains no self-knowledge, and as a result has no power to counter the car’s sinister influence. That leaves only his girlfriend Leigh (Alexandra Paul) and his jock best friend Dennis (future Blue Crush director John Stockwell) to fight the machine, but neither character (nor the actors playing them) has enough presence to take over as protagonists. Which leaves the movie as little more than a plot operating with (pardon me) mechanical efficiency.

But there are some fine supporting performances – particularly Roberts Blossom as the strange guy who sells the car to Arnie and Robert Prosky as the cranky old guy who runs the scrapyard where Arnie rebuilds the car. Carpenter comes up with some very effective visuals as Christine hunts down and kills Arnie’s enemies, and when it restores itself after being smashed with sledge hammers – and most spectacular of all, when it emerges from an exploding service station and becomes a rolling fireball chasing one of those enemies down a highway at night.

Despite the narrative weaknesses, Christine is a sharply satirical evocation of the way a young guy’s identity can become inextricably fused with his vehicle – which in Arnie’s case actually becomes his whole identity.

The Sony-Columbia Blu-ray has three featurettes, a collection of extraneous deleted scenes, and an engaging commentary track with Carpenter and Gordon originally recorded for a DVD special edition in 2004.

*

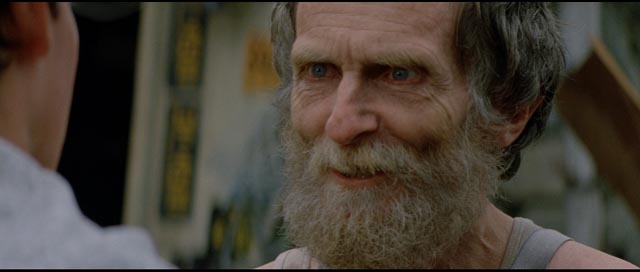

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (W.D. Richter, 1984)

If B-movies are viewed more from the point of view of form and content than budget, then things like Star Wars and Indiana Jones fit easily into the category. These are unabashed pastiches of old Saturday afternoon serials dressed up with big-budget technical resources. I was never a fan of those Lucas and Spielberg products; my tastes run more towards movies which play with genres rather than simply reiterating them … films which often seem to confuse critics and general audiences because their tendency to mix multiple genres confounds expectations. Even when the mixture isn’t entirely successful, I enjoy the attempt (like Gordon Hessler’s bizarre patchwork horror-thriller Scream and Scream Again [1970], which I’ve just rewatched on Blu-ray from Twilight Time). One of my favourite John Carpenter films is Big Trouble in Little China, a horror-comedy-trucker-martial-arts-fantasy which is narratively inventive, very funny, and packed with visual invention.

Although not a commercial or critical success when released in 1984, W.D. Richter’s The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (the best film in this particular list) has gradually developed a cult following on video, but is still not given the recognition and appreciation it deserves. Part adventure, part science fiction, part comedy, with even a touch of musical, it represents one of those rare moments when so many disparate elements blend together in perfect balance; Richter and writer Earl Mac Rauch create and sustain a consistent tone of straight-faced comedy which allows the bizarre and convoluted action to play out as a satisfying pulp narrative while affectionately mocking the absurd excesses of those same Saturday matinee serials. Buckaroo and his Hong Kong Cavalier cohorts are a more satisfying team of heroes than Marvel’s Avengers could ever be, and they do their stuff without needing super powers, just native intelligence and well-honed technical skills.

The plot itself is pure pulp simplicity: evil aliens from Planet Ten have been banished to the 8th Dimension, but when Professor Nikita and Dr. Emilio Lizardo invent the oscillation overthruster, a portal is briefly opened in the late ’30s, allowing some of these aliens to break through into our world – which happens at Grovers Mill, New Jersey. This invasion is covered up, thanks to the aliens’ ability to use Orson Welles as an unwitting front with his “faked” Halloween 1938 radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds to mask the real event.

While these Red Lectroids hide out at the YoYoDyne factory in New Jersey, biding their time until they can return to Planet Ten and seize power, they support themselves by developing advanced technology and weapons for the Defence Department. Their leader, however, Lord John Whorfin, has taken possession of the body of Dr. Lizardo, with the resulting derangement sending the scientist to a mental institution.

Many years later, Buckaroo Banzai, physicist, brain surgeon, musician and band leader, perfects the oscillation overthruster and unwittingly sets in motion the Red Lectroids’ plans to escape Earth and return to their own planet. This development has caught the attention of Planet Ten’s ruling Black Lectroids, who turn up ready to destroy Earth unless the Red Lectroids’ scheme can be averted. It’s up to Buckaroo and his team to sort things out before the world is destroyed.

Within this narrative, Mac Rauch and Richter load the film with rich layers of detail – the personal stories of many of the characters, visual and verbal asides which are often left unexplained but add a sense of the story’s world going beyond immediate events – while the actors maintain an impressive balance between playing it straight and pushing the limits of parody. Nothing fazes Buckaroo and the Cavaliers, no matter how absurd things get. The Red Lectroids are a bunch of crass rednecks while the Black Lectroids are Rastafarians; Buckaroo and his team take time out to perform in night clubs; the aliens bicker and argue among themselves. And there’s even time for romance as Buckaroo meets Penny Priddy, who looks just like his dead wife and turns out to be her unknown twin sister, separated at birth.

Richter, an impressive screenwriter himself (Invasion of the Body Snatchers [1978], Dracula [1979], Oscar-nominated for Brubaker [1980]), made his directing debut with Buckaroo Banzai, seeming to pour everything he knew about filmmaking into this first effort – the commercial failure of which stalled his directing career (he has only one other credit, Late For Dinner [1991]). In some ways, the film was ahead of its time. It seems likely that it has had some influence on Joss Whedon, much of whose work shares its self-aware tone and love of playing with genre expectations.

The cast is impressive – Peter Weller, Ellen Barkin, John Lithgow, Jeff Goldblum, Christopher Lloyd, Matt Clark, Clancy Brown, Rosalind Cash, Lewis Smith – and, although the effects may seem “dated” to an audience raised on the slickness of CG, the film’s design is as rich and idiosyncratic as its storytelling.

Arrow’s Blu-ray carries over some of the extras from an earlier DVD special edition, including an engaging commentary by Richter and Mac Rauch (in the persona of “real-life” Hong Kong Cavalier Reno), which treats the film as a spiced-up docudrama based on the “real” Buckaroo’s adventures, while still managing to fill in a lot of detail about the problems Richter faced with a producer (the notorious David Begelman) who tried to push the production in a more straightforward action direction. The disk image looks as good as it’s ever going to get, with rich colours and a nice film texture, and the extras go a long way towards explaining why its fans are so passionate about this unique and original movie.

Comments