Criterion Blu-ray review: Ettore Scola’s A Special Day (1977)

One of the loveliest, and most delicate, moments in postwar Italian neorealism occurs about a third of the way through Vittorio De Sica’s Umberto D (1952). While the film concerns itself with the plight of a pensioner struggling to survive in the economic chaos left in the wake of the collapse of fascism, it pauses for almost five minutes to observe the household servant girl Maria (Maria Pia Casilio) as she wakes in the early morning and goes about her chores. In real time, we see her lighting the gas burner, filling a kettle, grinding coffee beans, going through motions she has obviously gone through countless times before. But within and around these small tasks, we are allowed to see something else, something much deeper.

Maria pauses to stare out of the kitchen window at the bleak courtyard of the apartment building, watching a cat prowl over a roof. And as she stands by the stove, the camera moves in closer, observing her distant look, her eyes glistening with incipient tears as her hand moves gently across her belly. A small gesture which speaks of emptiness and a deep longing. This silent sequence evokes a profound sense of isolation, of sadness, the devastation of a life constrained and absent any possibility of independence.

This sequence came to mind repeatedly while watching Ettore Scola’s A Special Day (Una giornata particolare, 1977), seemingly referred to directly and indirectly throughout. The long shadow of neorealism is apparent everywhere in Scola’s quiet, deeply moving film, although unlike its predecessors it has a more polished quality, with at times quite elaborate camera choreography and, more particularly, the presence of two great stars in the lead roles.

A Special Day opens with a six-minute montage of newsreel footage from May 6, 1938, the day Adolf Hitler made a state visit to Rome, confirming the alliance of fascist states as the world moved inexorably towards war. The city is in a fever, with grand plans for parades and demonstrations of military might and social cohesion rooted in fascist principles. Having established this historical context, Scola introduces us to a monumental residential complex, a kind of vertical city which subtly evokes the social elements of fascism. This building has the distinct aura of Nineteen-Eighty-Four with its dense warehousing of citizens and an omnipresent sense of being observed, a pronounced lack of privacy which is continually emphasized by the endless radio broadcast of the day’s events blared over speakers in the courtyard and, more subtly and sinisterly, by the unavoidable presence of a prying, mean-spirited concierge who keeps tabs on the residents with the obvious intention of enforcing conformity.

The narrative proper begins with a rich sequence depicting the awakening of one particular household; the camera cranes in towards windows high above the courtyard and moves effortlessly into the apartment where it follows a middle-aged woman, Antonietta (Sofia Loren), as she rouses her six children and her loutish husband (John Vernon) on the “special day” of the title. Although the large flat seems crowded, her husband wants a seventh child because the larger the family, the better in terms of his position as a party functionary. Antonietta is defined by her role as wife and breeder of children, taken for granted by her family, who are all eagerly preparing for their roles in the day’s celebrations. As for the housewife and mother, she will not be joining them. With no servant, she is staying to do the housework.

Here is a kind of answer to the longing of the servant girl Maria in De Sica’s film, a life in which that emptiness is filled with the things Maria lacks, and yet the role assigned to Antonietta is just as oppressive and incapable of satisfying her inner needs. Neither woman is able to define herself.

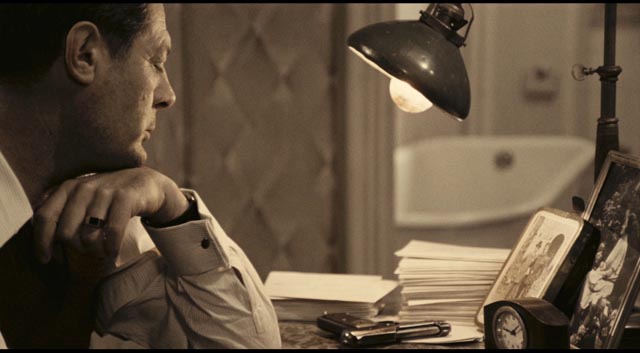

Once the population of the building has poured out through the courtyard, with Antonietta seemingly left alone in the vast edifice, chance steps in: she inadvertently releases a pet Mynah bird which escapes through an open window and flies across the courtyard. As she looks across, Antonietta sees a man in the opposite apartment and we cut to him. Gabriele (Marcello Mastroianni) is sitting at a desk going through papers. There is immediately something unsettling apparent as a gun lies on the desk beside him. We sense that he is struggling with thoughts of suicide. The tension in him is abruptly broken when Antonietta comes to his door, hoping to reach her bird through his window. Although agitated, he is unable to put her off. Here there seems to be a subtle shift in the film’s approach, from its almost neorealist observational style to something more literary, even theatrical. It becomes a chamber piece, prising out layers of psychological nuance through a series of lengthy encounters between Antonietta and Gabriele throughout the day.

Through this contact, Antonietta gradually becomes aware of all she’s been suppressing, her faith in fascism and Il Duce and her assigned role exposed as not simply false, but a complete contradiction of who she is, her essential nature. Gabriele awakens deeper feelings, the irony here being that his own isolation arises from his homosexuality, a fact which inherently blocks the romantic feelings he inspires in Antonietta. His deviance sets him entirely outside fascist society, fired from his work as a radio announcer, shunned because he fulfills none of the roles assigned to men – husband, father, soldier. But despite the pair’s conflicting sexual identities, they share something deeper, their condition of being outside the monolithic society which surrounds them. Through the day, they achieve an emotional connection which, ever so briefly, gives each of them confirmation of self-worth.

As the building’s inhabitants return from their day of celebrations, and as Antonietta watches Gabriele being taken away into exile by the authorities, there is a suggestion that she may now resist her husband’s coarse imposition of his definition of her role.

A Special Day is a rich and subtle drama which skillfully avoids melodrama and sentimentality while nonetheless evoking deep emotions in its characters and audience. Scola’s staging and camerawork are beautifully controlled, and Loren and Mastroianni, in atypical roles, do some of the finest work of their considerable careers. There isn’t a trace of caricature in either performance; these are fully-fleshed, complicated people, and their humanity stands as a contrast to and rebuke of the monstrously controlling society around them – that contrast continuously emphasized by the aggressive background of the ongoing radio broadcast of the day’s events which we hear throughout every scene.

The photography of Pasqualino De Santis fully supports the film’s themes, its desaturated colour palette reflecting a kind of monochromatic psychological and emotional state imposed by the political environment which traps Antonietta and Gabriele and against which their tentative awakening exerts a hopeful counter-force.

The disk

The 4K transfer used for Criterion’s Blu-ray, using a 2014 restoration by the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia-Cineteca Nazionale, provides a visually subtle presentation of De Santis’ distinctive cinematography, evoking a time when personal emotional energy was replaced by the false energies of a monolithic state. The mono soundtrack offers a fine balance between the quiet interactions of the characters and the bombastic presence of the relentless radio propaganda.

The supplements

The extensive supplements include an interview (21:13) with director and co-writer (with Ruggero Maccari) Ettore Scola in which he discusses his intentions with the film; an interview (14:37) with Sofia Loren who talks about her trepidation in taking a role which worked against her glamourous image; a short film starring Loren called Human Voice (2014), based on a play by Jean Cocteau and directed by the actress’ son Edoardo Ponti, in which a woman has one last desperate phone conversation with a man who is abandoning her for another woman; and a two part talk show appearance by both Loren and Mastroianni (28:03, 28:04) from 1977, around the time A Special Day received its U.S. release, in which the actors engage in a charming, relaxed conversation with Dick Cavett which ranges over their past collaborations and Scola’s film in particular. Finally, there’s a trailer (2:47) and an insightful booklet essay by critic Deborah Young.

Comments