Criterion Blu-ray review: Jean Renoir’s La Chienne (1931)

Jean Renoir, the son of one of France’s most famous painters, began making films in the mid-’20s. Because of his privileged background, and perhaps because most of his silent films starred his wife Catherine Hessling, he was seen as an amateur, a dilettante. When sound arrived, he faced producer skepticism about his ability not only to make a film on budget, but also to make one which would be commercially viable. To prove himself responsible, he quickly wrote, shot and completed a short feature adapted from a farce by Georges Feydeau. The material itself held little interest for Renoir – it deals with a mother’s efforts to get her constipated young son to take a laxative while the boy’s father tries to persuade a buyer for the military to put in an order for unbreakable ceramic chamber pots for every man in the army – but it served its purpose by proving the director’s practical skills and reliability. It also gave him opportunities to play with sound and, in its literal toilet humour, gave expression to a child-like impishness which was one facet of his personality.

With On purge bebe (1931) released and making money, Renoir obtained backing from producers Pierre Braunberger and Roger Richebe for the film which would establish him as a major director and go a long way towards defining him as the artist we are now familiar with. La Chienne (also 1931), adapted by Renoir from a novel by Georges de la Fouchardiere (and a previous theatrical adaptation by Andre Girard and Andre Mouezy-Eon), has however had a relatively low profile in his filmography and has proved more difficult to see than most of his other films.

The film begins with a brief prologue in which three puppets argue about the nature of the story we are about to see. One says it is not a comedy, a second says that it isn’t a tragedy, while the third says that it has no moral at all. This playfulness is belied by the bleak story which follows, a story which has elements of both comedy and tragedy, while as in so much of Renoir’s work, the audience is forced to draw its own conclusions about what it all means. While Renoir’s famous dictum that “Everyone has his own reasons” gives much of his work an air of tolerance and understanding, evoking empathy for all the characters, even those who might traditionally be viewed as villains, La Chienne is darker and more disturbing.

Maurice Legrand (Michel Simon, who had previously worked with Renoir twice and the following year would star in the director’s breakthrough Boudu Saved From Drowning) is a clerk at a hosiery company, married to Adele (Magdeleine Berubet), a shrewish wife who is constantly comparing him to her first husband, Sergeant Godard (Roger Gaillard), who died heroically in the war. Legrand’s only relief from his tedious life is his painting, about which Adele is always complaining. One night after leaving a gathering of company employees (during which Legrand is cruelly mocked by his fellow workers), he happens across a woman being assaulted by a man. He rescues Lulu (Janie Marese) from Dede (Georges Flamant) and escorts her home. Because he was dressed in his best for the work party, she believes him to be well-to-do and nurtures a relationship. The naive Legrand doesn’t realize that she is a prostitute and Dede her pimp, and that the pair merely want to exploit him for whatever they can get.

Legrand sets her up in a flat and moves his paintings there. Dede, always looking to make a profit, takes a couple of pictures to a gallery, presenting them as the work of “Clara Wood”, a previously unknown American artist. The gallery owner and a critic who happens to be present immediately set to work to build up a reputation for “Clara Wood”. Interestingly, when Legrand sees one of his paintings in the gallery window, he isn’t particularly concerned. His obsession with Lulu has supplanted his interest in painting and he doesn’t begrudge her this exploitation of his efforts. Meanwhile, Lulu’s masquerading as Clara Wood allows Renoir to satirize the art world he knew so well from his father’s experience; Lulu’s position as prostitute blends seamlessly with her new role as an exploitable commodity among gallery owners, critics and buyers.

As Lulu’s demands become more pressing, Legrand turns to embezzling from his employer. Then one day Sergeant Godard shows up; he had taken another man’s identity in the aftermath of a battle, escaping his old life and his wife by faking his death. He attempts to blackmail Legrand, who is no longer legitimately married to Adele, but Legrand tricks him into exposing himself, thus freeing Legrand from the marriage and, he thinks, clearing the way for a permanent relationship with Lulu. Needless to say, she has no interest in this and when he discovers her on-going relationship with Dede she mocks him for his gullibility.

This is where the comic, satirical strains of the film turn to tragedy with an act of irrevocable violence. And this is also where the question of the film’s moral position becomes complicated. Legrand has been a rather clueless figure, a target of others’ mockery, and yet he proves capable of violent anger. But his well-known persona allows him to escape the consequences of his terrible act, while quietly allowing another to be saddled with his own guilt. Our empathy for this rather sad little man is clouded by his own lack of conscience. And strangely, with Adele out of his life and fired from his job for the embezzlement, Legrand finally seems to be free and happy, becoming a bum who some years later runs into Godard, also now free because Adele has died, and the two of them set off in the film’s final moment to find a drink together.

In the end, La Chienne passes no judgement on Legrand, a very different conclusion from Fritz Lang’s Hollywood remake, Scarlet Street (1945), in which the equivalent character ends up tormented almost to madness by his guilt. Renoir presents his sordid story like a curious anthropologist observing strange customs, allowing Legrand to go his own way, dealing with his life and actions on his own terms. In retrospect, the film’s earliest scenes show a man detached from his own life, socially inept, out of sync and barely aware of the mockery directed at him by virtually everyone he meets. In a sense, it’s only when that entire life gets wiped away that he becomes comfortable in his own skin. He ends with nothing materially, but is finally happy.

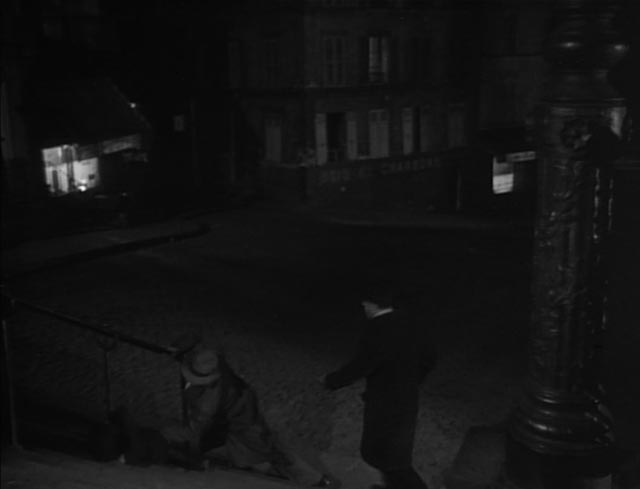

Seen as a kind of proto-noir, La Chienne works against that genre’s fatalism and in its oddly cheery conclusion creates a more unsettling view of the world, one in which things don’t always fall into line with some stern morality. Here are the roots of Renoir’s position as a sympathetic observer of human behaviour in all its forms. Here also are the roots of the style he would develop and refine throughout the rest of his career: a fluid camera which creates a deep sense of space fully occupied by the characters, a world which extends beyond the frame to include other lives, other events and other stories only fragments of which we may glimpse. This creation of a world rooted in reality, yet evoked poetically, is deeply enhanced by a sophisticated use of sound – just as other great directors grasped the potential of the new technology to extend the creative possibilities of the medium (Lang in M, Pabst in Die Dreigroschenoper, Hitchcock in Blackmail), Renoir uses sound to bind together spatially separated areas and evoke events taking place off camera, most notably in the film’s violent climax as we move repeatedly between Lulu’s bedroom and a street singer outside around whom a small crowd gathers, his song commenting on the unseen events in the private space above.

Renoir also innovated with the use of direct sound on location, shooting in the streets of Montmartre and recording dialogue in the rain, with the sound of water running through the gutter at the characters’ feet. This kind of thing was extremely difficult at the time, given the relatively primitive equipment available, yet it adds a deeper sense of reality to the story. The photography by Theodore Sparkuhl, who had previously worked many times with Ernst Lubitsch and had also shot On purge bebe, is also richly expressive with wonderfully evocative night exteriors and interiors from which we repeatedly get glimpses through doors and windows of the world outside.

And as in all of Renoir’s work, the cast is crucial to the film’s success, with Michel Simon lending a distinctive physicality to the downtrodden Legrand. Although the film’s women are perhaps less nuanced than in later movies, both Magdeleine Berube as Adele and Janie Merese as Lulu are strong presences, while Georges Flamant is excellent as the despicable Dede.

La Chienne is an accomplished work which deserves to be as well-known as Renoir’s subsequent films and Criterion’s excellent Blu-ray edition should greatly aid in its rehabilitation.

The disk

The 4K transfer made from a fine grain master printed from the original nitrate negative looks terrific, with rich blacks and a pleasing degree of film grain. The sound exhibits the usual limitations of a film from this period, but the dialogue is clear even when ambient noise (like rain) is present; given that this was recorded on location and not layered in later in a mix, it’s quite remarkable.

The supplements

The disk comes with a generous selection of extras, beginning with one of Renoir’s introductions recorded for French television in the ‘60s (2:45). He briefly fills in the background of the production, concentrating more on the “trial run” of On purge bebe rather La Chienne itself. As always, the filmmaker is an engaging presence.

Also included is a restored copy of On purge bebe itself (52:01), a minor work, but nonetheless amusing, with Michel Simon appearing as the military buyer who finds himself caught in the middle of a very peculiar family situation.

An interview with Renoir scholar Christopher Faulkner (25:24) covers the director’s transition from silent to sound, from amateur to professional artist and offers a reading of the film’s parallel depictions of prostitution and art.

Finally, there is a lengthy 1967 piece from French television, Jean Renoir le patron: Michel Simon (1:35:13), a conversation between Renoir and Simon, shot informally with handheld cameras in a restaurant, and directed by Jacques Rivette. It’s fascinating to watch the two ageing icons of French cinema chat about their careers and their long friendship and to see the engaging child-like play they slip comfortably into as Rivette and his crew prod them with questions.

The booklet essay is by Ginette Vincendeau.

Comments