Genre play in Germany

Pastiche, parody and irony have been all but exhausted as a creative strategy in the past couple of decades, largely because they’ve become a lazy excuse for filmmakers not to take their own work seriously. Which, in turn, tends to signal a degree of insecurity about how that work will be received by an audience. It’s easier to signal that what you’re doing is intended as some kind of joke than to risk having people laugh at you because you’re sincere about your material – particularly when it comes to genre movies. (Part of the unrelenting hostility which has greeted most of M. Night Shyamalan’s movies seems to be a response to the idea that “he takes himself too seriously”.)

I didn’t sense this kind of defensiveness in a couple of thrillers made in Germany thirty-five and forty-five years ago, both released on Blu-ray last year in excellent editions, and yet both push their genre elements to extremes which transform them into self-reflexive comedy. I think the big difference is that these two movies show their directors exploring the elements of genre and style from a position of familiarity and affection, rather than as a way to pander to a jaded audience. In fact, the earlier of the pair was greeted largely by puzzlement, a confusion about what the filmmaker was trying to do, because the manipulation of genre actually seems like an assault on audience expectations.

Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street (Sam Fuller, 1972)

By the time Sam Fuller made Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street in 1972, he had written and directed about twenty movies in various genres – western, war film, crime and melodrama – many of which were notable for a degree of lurid excess which already hinted at parody and satire directed at accepted American attitudes to issues of race and class. In more recent movies like Shock Corridor (1963) and The Naked Kiss (1964), he seemed determined to spit in the face of “good taste”. This pair came at the end of a successful fifteen year run which began with the western I Shot Jesse James (1949) and included war films like The Steel Helmet and Fixed Bayonets! (both 1951), which were rooted in his own experiences in World War Two and determinedly de-romanticized the soldier’s experience, as well as the great Pickup on South Street (1953), a noir which treated the Commie scare and patriotism with deep cynicism. Fuller complicated issues of national identity, patriotism, and simplistic concepts of what constitutes “the enemy” in movies like House of Bamboo (1955), China Gate and Run of the Arrow (both 1957), Verboten! and The Crimson Kimono (both 1959).

But by 1972 his career had seemingly run aground. After The Naked Kiss (one of his best films), he spent a few years working in television before returning to features with the severely compromised Shark! (1969)[1]. When that project went nowhere commercially, Fuller was idle again for several years until German producer Joachim von Mengershausen hired him to write and direct an episode of the long-running television cop show Tatort (1970 to the present, with an average of 20-30 feature-length episodes a year!).

What Fuller came up with shoehorned one of the series regulars, Sieghardt Rupp as customs officer Kressin, into a fairly deranged narrative about American private eye Sandy (Glenn Corbett) arriving in Germany to find out what’s behind the killing of his partner (yes, shot down on Beethoven Street). The plot itself becomes pretty convoluted, revolving around an international blackmail ring which has been compromising various politicians and diplomats by drugging them and taking photos of them posed in sexual positions with women – including Christa (Fuller’s wife Christa Lang), with whom Sandy becomes involved. Typical of Fuller, people’s emotions and loyalties remain murky; the characters may or may not be sincere with each other, and even if they are sincere, they’re probably nonetheless playing each other for advantage.

All of this initially looks like a typical B-movie set-up; but Fuller pushes everything in bizarre directions which turn the familiar elements of the thriller into an absurd commentary on the genre. This process begins early, in an extended sequence between Sandy and Kressin in which the characters speak two different languages, with little indication that either understands the other – a device used in each of their subsequent encounters. This undermines the very idea that it’s really possible to know or understand what’s going on. It’s also unexpectedly very funny. As the film progresses and its story becomes more absurd and confusing, Fuller seems to be pointing to the inherent ridiculousness of the espionage thriller itself. The deceptions and betrayals become something forced on the characters by the genre, rather than an expression of any recognizable psychological imperatives. It is this exposure of narrative absurdity which ended up confusing audiences and critics at the time of the film’s release; it could by (mis)interpreted as Fuller making fun of an audience which might come to this kind of movie expecting to take its narrative nonsense seriously.

Seen now, decades later, it’s possible to conclude that Fuller was simply being playful while giving his intended audience credit for being smart enough to join in the game with him. As a self-conscious critique of genre, Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street is a funny and entertaining romp through genre tropes (including a nod to Fritz Lang and the Dr. Mabuse series towards the end, when Anton Diffring turns up as the head of the blackmail operation, using video screens to communicate with his minions from the back office of a fencing school). Although made cheaply, its rough-and-ready style plays to Fuller’s strengths as a director; although commissioned for German television, and more specifically for an on-going series, he was given free reign and left to his own devices and you can sense him enjoying a liberty which hadn’t been available to him since the early ’60s, and wouldn’t really be available to him again for another decade, when he made White Dog (1982). (His attempt to make a definitive statement about war with The Big Red One [1980] suffered from producer interference, being severely cut down before theatrical release, and only “reconstructed” into a longer, supposedly more faithful version some years after the director’s death in 1997.)

Olive Films’ Blu-ray features a pretty good transfer in the original television aspect ratio (approximately 1.44:1), with decent image and sound quality. This is the longer “restored” cut – 127 minutes, as opposed to its original 102-minute theatrical cut (which I haven’t seen and so can’t compare). But apart from making what had been a rare, and obscure, part of Fuller’s filmography available at long last, the disk also includes another excellent Robert Fischer documentary, Return to Beethoven Street: Sam Fuller in Germany (2016), which, at almost two hours, gives a full account of the production history and fate of Fuller’s film.

*

Kamikaze ’89 (Wolf Gremm, 1982)

Ten years after Fuller’s German adventure, Wolf Gremm tackled the thriller from a different angle with Kamikaze ’89 (1982), his adaptation of a novel by Swedish mystery writer Per Wahlöö (co-author with his wife Maj Sjowall of the seminal Martin Beck series of police procedurals from the late ’60s to the late ’70s, which essentially invented the now-extensive genre of “Nordic noir”). That novel, Murder on the 31st Floor, was one of a pair of bleak dystopian mysteries about police commissioner Jensen, who investigates crimes in an oppressive, slightly futuristic fascist state. The novels are both pretty grim; Gremm’s adaptation of the first is very close in terms of plot, but is tonally quite different.

In fact, Kamikaze ’89 seems closer stylistically to Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s World on a Wire (1973), which itself was adapted from a dystopian science fiction novel by Daniel F. Galouye (remade in 1999 by Josef Rusnak as The Thirteenth Floor). This may or may not have something to do with the fact that Gremm cast Fassbinder in the lead role of Jensen. The look of Kamikaze ’89 certainly seems nothing like the glimpses of Gremm’s other work seen in the disk’s supplements.

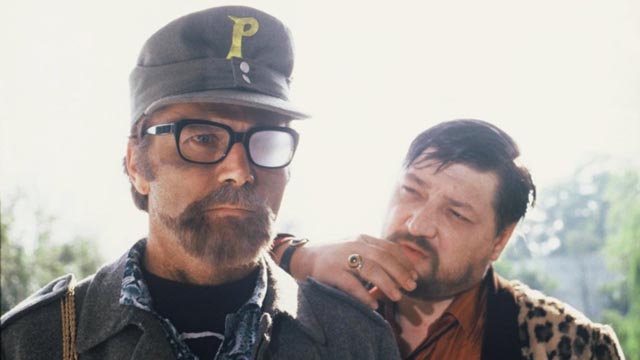

The film’s future, as in Fassbinder’s earlier film, is all garish colours, exaggerated action and modernist architecture repurposed to represent an oppressive sense of inhuman politics. Fassbinder as Jensen is a driven, amoral investigator dressed in an outrageous leopard-skin suit. Initially assigned to investigate a bomb threat at the offices of The Combine, a multimedia corporation which controls all news and entertainment in this society (with programming which includes a national “laughing contest” which goes on for days), Jensen disobeys orders from his superiors to drop the case as he gradually digs deeper and eventually uncovers not so much the actions of a terrorist underground as the truth about the crimes committed by the social overlords who run The Combine itself.

The dark political satire of the novel is transformed into an absurdist comedy about a fascist state which incorporates all political opposition into its own structure. By co-opting the opposition, keeping them busy in the production of critical counter-media which are never quite ready for release, The Combine silences all voices except those which serve its own purposes. In essence, the fascist Right uses the ineffectual Left to bolster its own power … in this, perhaps the film is a little too prescient for comfort as it seems that whatever the Left does these days somehow ends up strengthening nasty Right-wing political movements.

Although it was made in the early ’80s, Kamikaze ’89 seems to hearken back to the kind of Pop Art cinema of the ’60s and early ’70s, which used eye-popping visuals and a kind of comic book attitude for satirical purposes – Joseph Losey’s Modesty Blaise (1966), Elio Petri’s The 10th Victim (1965) and Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970), as well as Fassbinder’s World on a Wire. The presence of Fassbinder in the lead role adds a layer of cinematic self-referentiality, not to mention a pronounced comic tone, which lightens the political satire and nudges the film more towards a humorous commentary on the thriller genre rather than a deeper consideration of the dangers of an alliance between corporate media and Right-wing political forces.

Like Olive’s Fuller release, this disk from Film Movement has substantial supplements which increase its value beyond the film itself. There’s an hour-long documentary by Gremm which includes not only behind-the-scenes material from Kamikaze ’89, but also extensive footage of Fassbinder at work on his final film, Querelle (1982) – the doc is called Rainer Werner Fassbinder: Letzte Arbeiten, literally RWF: The Last Work (although the title is rendered as “The Last Year” in the subtitles and on the Blu-ray case). It’s interesting to see Fassbinder meticulously choreographing scenes in his highly stylized adaptation of Genet’s novel and how his directorial sensibility affected him on the set of Gremm’s film; although he doesn’t appear to have asserted any kind of directorial authority on Kamikaze ’89, he does exhibit an intense focus and attention to the details of performance in relation to the camera which were no doubt drawn from his experience on the sets of his own movies.

There’s also a commentary track from producer (and Gremm’s wife) Regina Ziegler, which is sparse but informative, particularly in its account of the relationship between Gremm and Fassbinder and the constraints of working on a small budget. And most strangely, a four-minute collection of radio spots in which none other than John Cassavetes uses various accents and vocal tics to promote the film’s U.S. release.

There’s also an additional DVD included in the package which contains Wolf at the Door, a 75-minute self-portrait of Gremm as he dealt with terminal cancer during the last three years of his life. It’s an intense, emotional and painfully revealing film which focuses as much on his inner struggle to remain positive – and creative – as it does on the grueling physical ordeal of disease and harsh treatments. He died in 2015 shortly after completing the film.

*

Both of these releases reveal their respective filmmakers as adventurous and playful explorers of the possibilities and limitations of genre and of cinema itself. And each offers rich supporting material to illuminate the creative spirits behind the features themselves.

________________________________________________________________

(1.) Released on Blu-ray by Olive Films in 2013, this adventure, written and directed by Fuller for a Mexican producer, and starring Burt Reynolds and Silvia Pinal, was disowned by the director after the producer had it extensively re-cut; the clumsy and awkward final product has Fuller’s cynicism – the hero is a crook with few redeeming qualities and everyone betrays everyone else – but it lacks his usual energetic storytelling, with too much of the movie ending up flat and dull. (return)

Comments