World Cinema Project 2: Criterion Blu-ray review

The tendency to classify, categorize and catalogue seems innate to the human mind. We are driven to look for connections and patterns. This is a way of organizing our experience of the world, to make sense of things by turning what may be random objects and events into meaningful narratives. The practice of history by its nature is a prime exemplar of this process – as has been repeatedly observed, more about the historian’s present than the actual, only obliquely knowable past.

The obsessive collector (and I confess to being one such) is also involved in a process of finding (or imposing) a kind of narrative order on the objects of his or her obsession. In my fairly substantial library of movies, I have many box sets and collections and the one thing all of these share is some kind of organizing principle – whether this is a focus on a particular director, or actor, or genre – which creates relationships among the various movies they contain.

But then occasionally there are sets which pose a challenge to this urge to organize disparate creative objects into a larger whole. Such is Criterion’s second set of films restored by the World Cinema Project (initiated by Martin Scorsese in 2007 in collaboration with The Film Foundation), which – like the first volume released in 2013 – collects six features from different countries, all of which had been at risk of being lost through neglect and decay. But beyond this effort to rescue these films, the selection is random, presenting no single way into the set. Despite brief introductions to each film by Scorsese and a short interview for each (15 to 20 minutes) with filmmakers and/or critics, plus an essay on each film in the accompanying booklet, as a viewer I can’t help but feel slightly hampered by my lack of familiarity with most of these filmmakers.[1]

And so, how to begin? Knowing which film I had the greatest prior interest in seeing (Edward Yang’s Taipei Story), I picked at random from the others and simply began working my way through the set towards that goal.

*

Law of the Border (Lütfi Akad, 1966)

Although I hadn’t heard of Lütfi Akad before, I had a glancing encounter with the work of the film’s star Yilmaz Güney several decades ago when I saw The Enemy at the 1981 Hong Kong Film Festival. This was one of several films written and produced by Güney while in prison, shortly before escaping to France; that film, directed by Zeki Ökten according to detailed notes provided by Güney, was a long and grim study of life in grinding poverty. Similar themes are apparent in Law of the Border, co-written by Güney with the pioneering Turkish director Lütfi Akad.

Located along the border between Turkey and Syria, the film centres on impoverished villagers whose only real source of income is smuggling, a dangerous pastime as the border is mined and patrolled by soldiers. These smugglers are exploited by local businessmen who pay them (not very well) for taking sometimes deadly risks to help them stock their stores with illegal goods.

Güney plays Hidir, the leader of a gang. After the murder of an officer stationed near his village, Hidir finds himself caught between that officer’s replacement Lieutenant Zeki (Atilla Ergün) and Ayse (Pervin Par), a teacher who wants to establish a school in his village. The Lieutenant, who is sympathetic to the villagers, and the teacher both represent an alternative way out of poverty, although the villagers distrust both of them. Zeki arranges with a local landowner to allow the villagers to farm his unused land and Ayse begins to teach the village children. But these alternatives to criminal activity are fragile and when the landowner spitefully arranges to destroy the villagers’ fledgling crops, Hidir returns to smuggling with tragic results.

One of the interesting questions raised by Law of the Border is how much the film’s material is rooted in the actual social and economic conditions of the people living in this part of Turkey, and how much of the film may be influenced by filmmaking conventions imported from elsewhere. In particular, there are strong echoes of the classical western genre – the men on horses, the gunfights and feuds, the harsh desert landscape. But beyond these physical elements, there are also thematic echoes: the border exists as both a physical and metaphorical boundary which seems similar to the boundary in the western between civilization and wilderness, between the freedom of lawlessness and the order imposed by the law, and between the self-determined individual and the constraints imposed by community. Is it mere coincidence, an indication that social structures and experiences are shared by distant, unconnected societies? Or have Güney and Akad deliberately drawn on the cinematic tradition of the genre which shares so many of these themes and narrative tropes? The opposition between crime and ignorance and education and progress is certainly universal, but the specific details of how that opposition is conceived in Law of the Border certainly seem to ally the film with the works of John Ford and other masters of the western.

Despite the sympathy the film displays for Lieutenant Zeki and Ayse, its critical view of economic oppression and the corruption of the landowning class caused problems with government censors, problems which later were aggravated by Güney’s conflicts with the authorities over political issues which resulted in prison terms; eventually the government ordered the destruction of all prints and elements, with just one surviving. This single print was the basis of the restoration and it’s by far the most problematic film in the set.

Rife with scratches, missing frames and pretty much every form of damage imaginable, it’s a very ragged viewing experience. Although not mentioned in the essay by Bilge Ebiri or the disk’s interview with Mevlüt Akkaya, there are narrative ellipses which suggest that the print may not be complete. According to the information provided, Law of the Border was a seminal work in Turkish cinema, its treatment of social and economic themes combined with Güney’s popularity as a movie star opening the way for the more politically engaged filmmaking of directors who were inspired by it.

*

Mysterious Object at Noon

(Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2000)

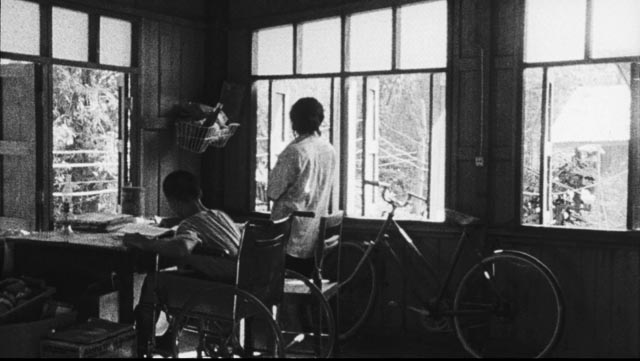

While the question of Hollywood influence hangs over Law of the Border, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s first feature, Mysterious Object at Noon (2000), seems to spring completely from its specific time and place. Apichatpong, who has since become a major figure in international cinema, used improvisational techniques as he traveled around Thailand recording various non-professionals as they added to a narrative in the manner of the Surrealist game known as the Exquisite Corpse, in which individuals sequentially add to a story (or drawing). The result is a dreamlike exploration of the creative process. That is, the film is both an evocative free-form fantasy rooted in a kind of oral folklore and a piece of meta-cinema which explores the construction of narrative and meaning. (Apichatpong eschews a director credit in favour of one which says “conceived and edited by”, leaving the question of authorship open.)

This was the only film in the set which I had previously seen, but my memory of it was quite vague. This viewing seemed more rewarding as I appreciated the interplay of the documentary element (the recording of the various individuals and groups as they add new details to the story) with the inventive flow of the narrative itself, parts of which are staged in more conventionally cinematic scenes.

The question of influence vs. coincidence is raised immediately in the film’s opening sequence: we see views of a small Thai town through the windshield of a moving vehicle while hearing a woman speaking off-screen. This combination of movement and revelatory voice is reminiscent of the work of Abbas Kiarostami, evoking the idea of penetrating the physical world while simultaneously uncovering individual subjective experience. In this case, we hear the woman recount her painful personal history of having been sold by her father as a child for the price of a bus ticket. Her story is intermittently interrupted with announcements of fish for sale … explained when we finally discover that we are traveling in a fishmonger’s van, the woman herself riding in the back.

When she finishes her story, an off-screen voice (the filmmaker’s) asks if she has any other stories. She seems a little puzzled about what he’s asking for. He says anything, fact or fiction. Although his question seems casual, it also seems strangely brutal, relegating her painful memory to the status of a mere “story”, its personal emotional weight disregarded. Nonetheless, she begins to relate another story, this one not personal, and seemingly invented in the moment. Here the film is launched into its exploration of the relationship between narrative and experience, the way stories become a device for exploring the world around us.

The woman tells of a crippled boy and his teacher, and of how something mysterious happens one day as the teacher appears to give birth to small, dense ball … the “mysterious object” of the title. From here, the story is taken up and embellished by a series of narrators. The object is declared to be a star which has fallen to Earth; the star is transformed into a boy who becomes companion to the crippled boy; seeking a closer relationship the star-boy transforms himself into a duplicate of the teacher, and the crippled boy has to decide which one is genuine.

As Apichatpong travels around Thailand, asking various people to add to the story, we are carried along by the flow of this narrative while being given glimpses of the way people live their own lives in the rural places he visits. The magical realist elements of the story being told come to be seen as a way for these people to enrich and explain their own experience of the world. This blending of the physical reality of these people’s lives with a mythic, even spiritual layer of meaning which permeates that reality is a quality which runs through all of the filmmaker’s subsequent work; Mysterious Object at Noon can be seen as a sketch of the themes he will later develop in greater depth.

Shot in 16mm black-and-white, the film nonetheless has some of the lush quality of the later colour films, although the monochrome emphasizes the documentary aspect; this provides a clearer view of the separation and interplay of physical and social reality with the subjective experience of that reality. In this, Apichatpong’s first feature is more deliberately analytical than the films which followed. Perhaps the fact that he had lived and studied in the U.S. had provided a degree of distance which allowed him to observe this place and its people simultaneously from an inside and an outside perspective. The film is curious about the lives of the people it observes, but never treats them with anthropological detachment; rather it immerses itself completely in their perspective.

*

Insiang (Lino Brocka, 1976)

Lino Brocka was a prolific Filipino director who averaged three movies a year over two decades. Just in terms of this volume, comparisons with Rainer Werner Fassbinder would seem justified. But judging by Insiang (1976) – his fifteenth feature – he had other affinities with his German contemporary … in particular, the use of melodrama as a vehicle for savage social commentary.

Insiang tells the story of the eponymous woman who lives a hard life in the slums of Manila. The money she makes taking in laundry is mostly handed over to her embittered mother, who is constantly fighting with the family of her sister who share the house with her and Insiang. After a big blow-up which ends with these relatives being kicked out, the mother brings Dado, her much younger lover, into the house. For him, it’s a matter of economic convenience; for her, it’s a way of staving off aging and the bitterness she still feels at being deserted by Insiang’s father.

With a boyfriend who refuses to commit to her in the only way that is meaningful – getting married so she can escape the family home – and relentless pressure from her mother’s predatory lover, Insiang is trapped. Having submitted to Dado, she gains an unsavoury reputation among her neighbours and rejection from her boyfriend. And so she comes up with a scheme to overturn this situation in a particularly brutal way, destroying both the lover and her mother.

Shot by Conrado Baltazar in saturated colour, with a mobile camera which prowls the slums in Insiang’s company, the film is superficially an overheated melodrama of sex, violence and desperation. But Brocka’s close and detailed observation of these characters and their milieu adds a critical layer of social and economic analysis; the characters are drawn in depth and we see how their innate personalities are shaped – and distorted – by circumstances beyond their control. As events tighten around Insiang, melodrama shifts inexorably into the register of tragedy – its ending reflecting back to an horrific opening sequence in which we see Dado at work in a nightmarish pig slaughterhouse.

It’s remarkable that a film so rich in imagery and performance was shot in just seven days. Like Fassbinder, Brocka had an obvious natural instinct for cinema. Insiang manages to combine a kind of neorealist observational skill with all the possibilities of dramatic construction to produce a work of wrenching emotional power. The cast is superb, led by Hilda Koronel as Insiang, Mona Lisa as her mother and Ruel Vernal as the lover Dado. Even the smaller roles are invested with depth and authenticity.

This film brought Brocka to international attention when it screened at Cannes in 1978 … but I confess I was completely unfamiliar with him and his work until this release (and the simultaneous release of Insiang with Manila in the Claws of Light on Blu-ray by the BFI). By far, my experience of Filipino cinema has been limited to often crude, sometimes imaginative genre movies by Eddie Romero and Gerardo de Leon (the one big exception being Romero’s hugely ambitious national epic Agila [1980], which itself deserves rediscovery). Perhaps more than any other film in this set, Insiang inspires an interest in exploring a previously little known national cinema.

*

Revenge (Ermek Shinarbaev, 1989)

Ermek Shinarbaev’s Revenge (1989) seems more familiar. Made in Kazakhstan just before the fall of the Soviet Union, it bears some striking resemblances to the work of the revered Georgian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov. Shinarbaev’s film uses colour and formal visual compositions in a similar way, linking elements of folklore and history to evoke poetically the forces which shape and constrain lives in a particular place and time.

The film begins with a prologue set in 17th Century Korea in which the childhood friendship of two boys – one a prince destined to rule, the other a poet – ends when the poet can’t stomach the brutality of his friend, who arbitrarily orders the execution of one of his servants. The poet is sent into exile, setting up the film’s theme of dislocation and lives driven off course by circumstances beyond individual control.

Jumping ahead to Korea in 1915, we see a drunken teacher angered by his students; he beats a young girl to death and flees. The girl’s father, driven by a desire for revenge which has been thwarted, takes a young second wife and has a son who is raised from birth with the single aim of tracking down the teacher. Once grown, this son sets off on a trek through China, eventually ending up in Sakhalin, an island whose own identity has continually shifted through history as different countries laid claim to it.

Revenge, although propelled by the desire to exact some kind of personal justice for the murder of a child, is primarily about lives consumed by an emotion which prevents any lasting attachment to a specific place. The script, adapted by Anatoli Kim from his own novel, reflects the author’s own sense of displacement as a Korean-Russian. The film’s formal qualities, as in many of Parajanov’s films, give the narrative an abstract quality, somewhat distancing the viewer from the immediacy of the emotions depicted. This is more morality play than dramatic narrative.

*

Limite (Mario Peixoto, 1931)

The most idiosyncratic film in the set is this Brazilian silent from 1931. The only film made by Mario Peixoto, it remains enigmatic even as it has been declared the greatest film ever made in Brazil. Peixoto was the son of an aristocratic family, probably born in Brussels, who went to school in England and traveled in England and France, where his interest in film exposed him to a range of influences. He asserted that the scenario for Limite was inspired by seeing a photo by Andre Kertesz on the cover of a magazine in Paris; back home in Brazil, he tried to interest other filmmakers in the scenario, but they encouraged him to make the film himself.

Limite is a dizzying work of invention and synthesis, drawing on the films of Surrealists like Jean Epstein and Luis Bunuel as well as the German Expressionists, but also summoning up original ideas which seem to have few antecedents. There is an oneiric quality which makes the film difficult to grasp on a first viewing, its non-linear construction leaving an impression of striking imagery which flows past with only the barest traces of a narrative.

A man and two women, apparently shipwrecked, drift in a small boat on the open sea. While the film repeatedly returns to these figures, we are given glimpses of what are presumably their previous lives in a series of flashbacks(?) which as often as not are elusive and inconclusive. The overall effect is one of destabilization and unease – perhaps the definitive moment of the film occurs in the sequence where one of the women surveys a vast landscape from a mountaintop and the camera abruptly becomes unmoored, swinging in wild arcs, spinning on its axis in a vertiginous evocation of psychological disorientation (a moment singled out for its startling innovation by Mark Cousins in his epic documentary The Story of Film).

Limite seems the work of a savant, someone who filled it with every idea he had about the medium, its idiosyncratic amalgamation of styles and techniques and original insights making it stand alone outside preexisting categories. It’s perhaps not surprising, then, that Peixoto never succeeded in making another film, all subsequent projects falling through; its very uniqueness seems to work against the idea of repeating the creative feat.

Meeting with confusion and indifference at its first few screenings in 1931 and 1932, it quickly became legendary – a small group arranged for private screenings, but it disappeared from public view. Talked about, but seldom seen, it acquired a mythic reputation – something which few works of art are likely to live up to when rediscovered later. Peixoto himself added to the myth, even concocting a laudatory essay about the film which he attributed to Eisenstein. But in this case, the film was kept alive by a handful of fans, including the critic Pedro Lima and the intellectual Plinio Sussekind Rocha, one of whose students, Pereira de Mello, having attended a screening, eventually rescued the deteriorating nitrate print (which had been seized by the police during the military dictatorship) and began what eventually became a years-long process of restoration. Without de Mello’s efforts, Limite would have vanished, leaving only those traces of myth. The Film Foundation’s restoration is based on de Mello’s work.

*

Taipei Story (Edward Yang, 1985)

To a viewer experienced in popular western cinema – including independent and foreign “arthouse” films – Edward Yang’s Taipei Story (1985) may well seem to be the most accessible film in this set. Although physically rooted in Taiwan, it’s a far cry from that society’s traditional family melodramas and martial arts movies. This is a depiction of urban alienation which is reminiscent of Antonioni; here amongst the soulless modern buildings of Taipei, characters repeatedly and chronically fail to connect with one another emotionally. There seems to be no past here and the present has a transnational placelessness which leaves the characters rootless.

The film opens with Chin (Chin Tsai) and Lung (Hou Hsiao-Hsien, who co-wrote the script with Yang and T’ien-wen Chu) looking over an empty apartment. It needs work, they agree. Chin comments that they can put shelving in the bedroom for a TV and VCR, so Lung can watch movies in bed. There is no sense of excitement or engagement between this pair; they decide that Chin will move in while Lung takes a trip to the States, hoping to line up work with his brother-in-law so that they can eventually move there.

Chin soon loses her job as a personal assistant to an executive at an architectural firm. The new owners are restructuring and the best they can offer is a secretarial position – an offer obviously intended to push Chin into resigning. She halfheartedly looks for another position through the rest of the film, while Lung’s business plans in the States fall apart. She’s angered when he gives money to her irresponsible (and, it turns out, abusive) father, further undermining their vague plans to emigrate. They drift apart. Chin has a fling with a young man who rides a motorcycle; a young man who becomes something of a stalker when she loses interest.

As in Yang’s other films (his masterpiece A Brighter Summer Day, and the international hit Yi Yi), Taipei Story is a work of severe formal beauty, its characters frequently rendered small and powerless in expansive architectural spaces. An air of ennui permeates the barely shared world of Chin and Lung and when the inertia is finally, abruptly shattered by an act of violence (as in A Brighter Summer Day), little actually seems to change. Yang’s view of modern Taiwan feels stifling and airless, but the desire to escape, to emigrate to the States, also seems futile. The film ends with a feeling of emptiness much like Antonioni’s L’eclisse (1962), too attenuated to be considered despair, but undeniably hopeless.

*

In searching for ways into the varied perspectives and cinematic styles of the six features included in Criterion’s World Cinema Project 2, I’m made aware of just how easy it often is to let a new movie slip into familiar categories, the seek the simplest and most direct way to understand it. Too easy perhaps. These six disparate films require a more active effort at interpretation – and quite possibly, the interpretations offered here miss a great deal because I can only approach them with my own preexisting ideas about cinema, which are inevitably rooted for the most part in European and North American cinematic models. Like its predecessor, this set opens windows which look out on, no doubt, much larger vistas of which these individual films are just fragments. Hopefully, as the World Cinema Project expands its work, other fragments will come into view and a more coherent image of these various national film cultures will emerge.

The disks

Criterion’s World Cinema Project 2 comes in a 9-disk, dual-format set, with three Blu-rays holding two films each, and each film getting a DVD to itself. Not surprisingly, given the various histories of the individual films, the visual quality of the set varies widely. The more recent films fare better, with virtually pristine transfers of Taipei Story, Revenge and Insiang. Mysterious Object at Noon is naturally grainier, given its 16mm origins, but the transfer is nicely textured, with natural grain and strong contrast supporting a lot of image detail. Limite, which is missing a section because of deterioration of the original elements, exhibits various degrees of damage, from scratches to full-blown nitrate decay. The worst image belongs to Law of the Border, with extensive scratching throughout and poor contrast as the source for the restoration was a print well removed from the original negative. Similarly, the soundtracks vary, although even the roughest are intelligible.

The supplements

As previously mentioned, each film has a brief introduction (about 2 minutes) from Martin Scorsese who offers a few quick observations to establish a basic context for viewing. And each has a brief on-screen commentary (15-20 minutes) to aid in understanding the origin and possible meanings of the films: historian Pierre Rissient on Insiang; director Apichatpong Weerasethakul on Mysterious Object at Noon; director Ermek Shinarbaev on Revenge; Brazilian filmmaker Walter Salles on Limite; Turkish producer Mevlüt Akkaya on Law of the Border; and filmmakers Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Edmond Wong on Taipei Story.

The accompanying booklet contains an introduction about the World Cinema Project by Abbey Lustgarten and individual essays on each film: Phillip Lopate (Insiang), Dennis Lim (Mysterious Object at Noon), Kent Jones (Revenge), Fabio Andrade (Limite), Bilge Ebiri (Law of the Border), and Andrew Chan (Taipei Story).

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) One of the films is Filipino filmmaker Lino Brocka’s Insiang (1976); the BFI has released the same restoration in a set which also includes Brocka’s previous feature, Manila in the Claws of Light (1976), plus extensive contextual supplements which provide a deeper understanding of this previously – to me – unknown filmmaker. (return)

Comments