Random thoughts: Summer 2017

There are things I’ve meant to comment on here recently, but which haven’t fit in with the longer reviews I’ve been writing – so here are some random observations and miscellaneous thoughts.

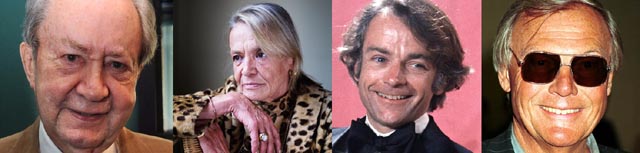

Passing

First, I’ve failed to note several sad deaths, beginning with Peter Sallis, who died on June 2 at the age of 96 after a seven-decade career as a character actor in everything from the long-running television series Last of the Summer Wine to Gordon Hessler’s Scream and Scream Again, with more than 150 credits in television and features. But for me, Sallis will always, and indelibly, be the cheese-loving, somewhat clueless inventor in Nick Park’s wonderful series of claymation films about Wallace and his much smarter dog Grommit.

On June 14, model and actress Anita Pallenberg died at 75. Best known for her involvement with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, she appeared in a number of edgy films which pushed the limits of the mainstream. She was the evil queen in Roger Vadim’s Barbarella, had a small role in Christian Marquand’s Candy, co-starred in Marco Ferreri’s Dillinger is Dead, and played one of Turner’s lovers in Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance.

On June 16, it was director John G. Avildsen, who was 81. Avildsen was a competent rather than inspired filmmaker who made a number of very popular movies during a fifty-year career which included Rocky, for which he won numerous best director awards, including an Oscar. Another hit was The Karate Kid, a similar tale of an underdog’s triumph. He guided Jack Lemmon to his second Oscar for his lead role as a morally compromised businessman in Save the Tiger. He also launched Peter Boyle’s career with the sour, reactionary Joe in which a hateful bigot goes hunting for hippies.

By a strange coincidence, news of Adam West’s death on June 9 came the day after I’d re-watched Byron Haskin’s Robinson Crusoe on Mars in which he had a brief supporting part just two years before landing the role which defined him, despite the fact that he had almost 200 credits over six decades. In 1966 he became Batman in the campy TV series which lasted three seasons. Strangely, what made that show a success was the impression that West gave of not being in on the joke. He played the Caped Crusader with a straight face and what seemed like complete sincerity, an attitude which just made the show seem even funnier.

*

Recent viewing

I’ve neglected a number of disks which deserve more attention, but I’ll just mention them here with perhaps longer reviews at a later date.

Although Tonino Valerii made one of my favourite spaghetti westerns, My Name is Nobody (1973), I hadn’t until now seen any of his other films – which include more spaghetti westerns, action movies and poliziotteschi. Arrow’s Blu-ray release of his second feature, Day of Anger (1967), reveals a less comic treatment of the central themes of My Name is Nobody. Lee van Cleef is Frank Talby, a legendary gunfighter who arrives in town looking to reclaim money stolen from him by a former partner, and just as importantly to get revenge. He meets and mentors the lowliest man in town, Scott (Giuliano Gemma), son of a prostitute who makes his living cleaning up everyone’s garbage. Talby feeds Scott’s resentment and transforms him into a deadly gunfighter, whom he uses in his plan to destroy the crooked leaders of the town. At first enamoured of his new power, Scott gradually develops his own moral sense and is inexorably drawn towards a final showdown with Talby. Day of Anger is a bleak movie which shares an overall structural similarity with My Name is Nobody, but the later film has a warm, elegiac tone completely absent here. (Arrow’s disk includes three versions of the feature, interviews with scriptwriter Ernesto Gastaldi and Valerii biographer Roberto Curti, an archival interview with Valerii, a deleted scene and trailers.)

*

Jean Rollin’s Les Echappees (1981) is not one of his best, but it plays variations on a number of his favourite themes. Two young women escape from a mental asylum and set out through the countryside, eventually hooking up with a group of traveling performers. When the troupe are raided by the police, the pair move on, making their way to a port, where they find shelter in a bar and are offered escape on a ship by another woman whose boyfriend is a sailor. But they are diverted by a group of hedonists who take them to a chateau where things go very badly. The carnivalesque atmosphere leads inevitably to disillusion and death. (The Kino/Redemption Blu-ray includes a 28-minute interview with Rollin.)

*

Although I found Night Shift (1982) and Splash (1984) fairly entertaining, for years I didn’t have much of an opinion of Ron Howard as a filmmaker. His work seemed to consist mostly of mainstream mediocrity – Far and Away, Willow, Backdraft, A Beautiful Mind, Cinderella Man, Ransom, The Missing and so on … But then a few years ago a friend kept insisting that I should watch Frost/Nixon (2008). I wasn’t that interested; after all, the story was extremely familiar from all the coverage it had received at the time and I couldn’t imagine what a docudrama by Howard could add to it. But I finally did watch it, and it was a riveting character study. As a fan of conspiracy thrillers, I decided to try The DaVinci Code (2006), but it was a tedious bore. However, the sequel, Angels and Demons (2009), turned out to be a rousing, fast-paced entertainment which – rather than ponderously taking itself seriously like its predecessor – reveled in the absurdity of its plot. Then came Rush (2013); although I have no particular interest in Formula One racing, this turned out to be another intense character study, made with a strong visual style. So, despite my misgivings about so many of his movies, I’ve recently found myself re-evaluating Howard to a degree. Which is why, although again I hadn’t much liked Apollo 13 when I saw it in a theatre in 1995, I picked up a copy of the Blu-ray on sale. This is a movie another friend regards very highly because of its attention to the technical details of space flight and the solving of problems under pressure. And watching it again, I had to agree; where before I had seen it as wallowing in patriotic sentiment, it’s actually a very restrained treatment of the near-disaster which almost killed three astronauts.

And so, having just re-watched and appreciated that movie, I picked up a copy of Howard’s third Dan Brown thriller, Inferno (2016), despite the near universally derisive reviews. Not as well-constructed as Angels and Demons, with a less compelling villain, it is nonetheless another fast-paced entertainment and the visions of Hell which plague Robert Langdon (Tom Hanks) are delivered with panache. (The Apollo 13 disk includes two commentaries — one with Howard, the other with Jim and Marilyn Lovell — plus multiple featurettes on the actual mission and the making of the film; the Inferno disk includes deleted scenes and multiple making-of featurettes.)

*

For horror fans, Spanish director Eugenio Martin is best (and fondly) remembered for Horror Express (1972), which unleashes a deadly alien in the confines of a trans-Siberian train heading from turn-of-the-century Manchuria to Europe. It’s one of those odd multi-national hybrids disguised as an English or American movie by the presence of English-speaking stars (Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, Telly Savalas). But its follow-up, A Candle for the Devil (1973), although it has an English star, is firmly embedded in contemporary Spain. Judy Geeson plays Laura Barkley, a young woman who visits a small town to join her vacationing sister. But when she arrives at the inn, she’s told her sister left abruptly early that morning, leaving no forwarding address. The audience, however, knows that the sister is dead, killed by Marta (Aurora Bautista), one of the two sisters who run the inn. The killing was semi-accidental, a result of Marta’s fury at the sister’s shameless sunbathing in view of the neighbours. Driven by sexual repression rooted in a rigid Catholicism, Marta becomes unhinged and begins bumping off each new young female tourist who makes the mistake of checking in, dragging her reluctant younger sister Veronica (Esperanza Roy) into her murder spree as Laura gradually figures out what’s going on. For the viewer there’s no mystery as we see Marta’s acts right from the beginning; the film is instead a dissection of religious mania and hypocrisy in a country where a powerful church imposes intolerable controls and restrictions on normal human feelings. (The Scorpion Blu-ray includes a 20-minute interview with star Judy Geeson in which she gives a very quick survey of her entire career, rather than an account of the making of this film in particular.)

*

Re-watching Tom Holland’s Fright Night (1985) for the first time in three decades, I was reminded why I’d never bothered to look at it again after seeing it on its initial theatrical release: although it has a decent if unoriginal concept (suburban teen discovers his new neighbour is a vampire, but no one will believe him), the story is so thinly developed, with every beat obvious and telegraphed, that rather than being entertained, I spent most of the 106 minutes irritated that Holland hadn’t made more effort when he wrote the script. Horror-comedy is a tricky thing, with a huge risk of the comedy undermining the horror – and less frequently, the horror turning the comedy sour – and here, although the situation sets up a promise of tension and scares, Holland mostly goes for the laughs (an approach which at its worst produces the gratingly annoying sidekick character Evil Ed [Stephen Geoffreys]). This movie has a very enthusiastic fan base and I guess I was hoping that my memory was faulty … but I’m afraid it wasn’t. (Eureka’s all-region, dual-format edition contains an insane quantity of extras: about 220 minutes of new and archival material PLUS a new two-and-a-half hour making-of doc.)

*

Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (1977), however, has aged very well, its strengths on full display on Arrow’s Limited Edition Blu-ray. Shot cheaply on 16mm, the film has a gritty, raw look which works well with the rawness of the story. The 4K scan from 35mm internegatives struck from the original 16mm camera negative maintains the grain, but brings out a lot of detail even in the extensive night sequences. A technical advance for Craven from The Last House on the Left, it is also more consistent in tone, ratcheting up the tension as it pits the two families – a lower middle class, multi-generational clan who get lost in the desert, and the desert-dwelling brood of degenerate cannibals who attack them – against each other in what becomes a mutual fight for survival. As the night progresses, glimmers of humanity emerge in Ruby (Janus Blythe), the daughter of head cannibal Jupiter (James Wentworth), while the respectable family devolves into its own primitive brutality. In the end, survival is not a matter of civilization triumphing – the fight has, in fact, stripped away every vestige of decency and morality. Craven had a long career with numerous ups and downs, and certainly he had far more commercially successful movies, but The Hills Have Eyes remains his finest work. (Arrow’s Blu-ray includes three commentaries: one with Craven and Producer Peter Locke from an earlier DVD edition; one with actors Michael Berryman, Janus Blythe, Susan Lanier and Martin Speer; and one with academic Mikel J. Koven, who concentrates on the film’s links with the legend of the Scottish cannibal clan of Sawney Bean. There’s a making-of doc, plus a couple of interviews, outtakes, trailers, and an alternate, slightly more upbeat ending.)

*

I first saw Mel Gibson in George Miller’s Mad Max (1979) and became a fan. He had genuine screen presence, a mixture of charm and barely suppressed menace. For most of the following decade, he appeared in a lot of Australian movies (or U.S./Australia co-productions) which consolidated his screen persona as a kind of romantic action star – the rest of the Mad Max trilogy, Peter Weir’s Gallipoli (1981) and The Year of Living Dangerously (1982), Roger Donaldson’s The Bounty and Gillian Armstrong’s Mrs. Soffel (both 1984) – but in 1987 he was almost instantaneously transformed when he starred in Richard Donner’s Lethal Weapon. He became more one-dimensional as a representative of over-the-top comic violence. The dangerous edge which had always been there took precedence, but now as a joke. This coincided with his move from Australian star to Hollywood player. While Miller had brought out the larger-than-life mythic element of Gibson’s screen persona and Weir had focused on the ways in which that persona could be contained in a more realistic, naturalistic context, Donner and Hollywood pushed him towards something closer to a caricature. And that caricature became a huge international success, appearing in a long string of action-comedies and thrillers. But something else was happening at the same time, perhaps tied to what gradually emerged about Gibson’s regressive religious beliefs. Channeled by Hollywood into often mindless entertainments, Gibson craved seriousness. He acquitted himself quite well in Franco Zeffirelli’s Hamlet (1990), but it was with his directorial debut in 1993 that something essential about him became apparent. The Man Without a Face reveals an almost fetishistic attraction to bodily mortification, which in retrospect reflects all the way back to the physical batterings he suffered as Max Rockatansky. He reveled in torture in his next directorial outing, Braveheart (1995), and it was the essence and purpose of his notorious follow-up, The Passion of the Christ (2004), which is a lovingly detailed two-plus hour depiction of the destruction of a single human body. Here we see that Gibson’s religious obsessions seem to have little to do with the spirit and everything to do with a fascinated horror of the physical.

So it’s not surprising that his latest feature, Hacksaw Ridge (2016), despite its surface text about religious conviction, is again almost hypnotically obsessed with smashed, torn and horrifically broken bodies. Which is not to say that it isn’t a very well-made film – Gibson is a talented director – but it is more interestingly a deeply conflicted film, based on the true story of Desmond Doss (Andrew Garfield), the only conscientious objector ever to be awarded the Medal of Honor for conspicuous bravery in battle. Having faced contempt and hostility from his fellow soldiers and officers, the combat medic single-handedly saved the lives of dozens of wounded men during the brutal Battle of Okinawa. Gibson manages to draw a nuanced performance from Garfield in a role which could easily have slipped into sentimental religiosity – someone who abhors the idea of violence, yet clearly sees the inevitability of war, Doss dedicates himself to doing whatever he can to alleviate the suffering which surrounds him. But as the film progresses, it becomes clear that Gibson’s real interest lies in that suffering; in three separate battle sequences which become increasingly hallucinatory, we see in graphic detail all the ways a body can be broken and split apart to reveal the messy mechanisms hidden beneath the fragile surface of the skin. Gibson finds beauty in the mortification of the flesh, using religious sentiment to justify that fascination. It seems that he would be more at home among Medieval flagellants than here in the secular present. (The dual-format release includes deleted scenes and extensive making-of featurettes.)

Comments