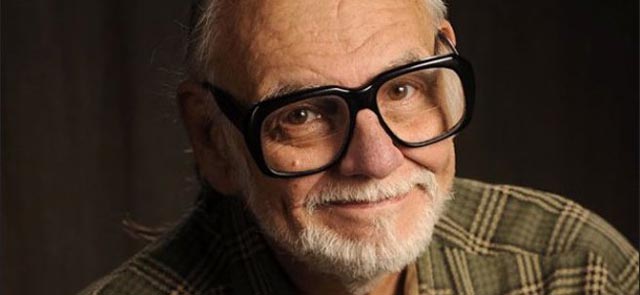

George A. Romero 1940-2017

Objectively, it seems implausible to claim a personal sense of loss when someone you’ve never met dies. But our lives are so saturated with connections through various media that we can’t help but come to feel a sense of close familiarity with people whose lives and work hold meaning for us. And thus I was surprised at how saddened I was to hear of George A. Romero’s death last weekend.

Romero holds an interesting position in cinema – an outsider whose work was weakest when he came closest to finding support from mainstream production companies, who nonetheless was hugely influential on the development of the modern horror film. Before Romero, the zombie was a minor figure, generally rooted in a popular conception of Voodoo. But with Night of the Living Dead (1968), zombies began their journey to genre dominance as probably the most ubiquitous monster in popular culture – but not as a manifestation of dark magic, mindless slaves controlled by sinister priests. Romero’s zombies were savage beasts driven by nothing more than an insatiable desire to eat the living. They became a visceral, terrifying metaphor for disease and death, as inescapable as our own mortality.

I first heard of Night of the Living Dead several years after it’s original release – probably from an interview with Romero in the Winter 1973 issue of Cinefantastique. But I remember more clearly a reference in the film column of an issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, in which the writer urged his readers to take any opportunity to see the film if it screened within a hundred miles. Well, I got my opportunity in the summer of 1974, when it was screened (from a 16mm print) as part of a summer horror series at the planetarium in Winnipeg. At the time I was living out in Neepawa, so I actually traveled about 110 miles to see it. The trip was worth it. The movie was everything I could have hoped – dark, intense, uncompromisingly bleak … and extremely well-crafted.

Even when Romero gained a degree of success and critics began to take notice, I don’t think he was given much credit for his craft. An experienced cameraman and editor from years of work on commercials and industrial shorts in Pittsburgh, he approached John Russo’s script with a real director’s eye. He didn’t do what so many low-budget filmmakers do and stage everything as simply as possible; he used a lot of coverage, crafting each moment through dynamic montage for maximum impact. This gives his work at its best both a visual density and a sense of dramatic urgency which he uses to great effect in several films which open in the midst of chaotic action (The Crazies and Dawn of the Dead in particular).

As he returned repeatedly to his zombies over the next forty years, Romero approached them from multiple angles. The dark nightmare of Night became the garishly colourful satire on consumer capitalism of Dawn (1978), then turned back to an even greater darkness in Day (1985); in Land (2005), he turned the zombies’ metaphorical power on economic inequality and class warfare; in Diary (2007), he turned to self-referential stylistic play through the use of found-footage tropes; and, in his final film, Survival of the Dead (2009), he returned to the intimacy of Night to create a moving family tragedy which hearkened back to the classic style of John Ford.

What emerged most clearly from these six very different films was not Romero’s love of gore (although he did approach graphic effects with exhilarating enthusiasm), but rather his interest in using extreme situations to explore how human beings interact with one another in, more often than not, destructive (and self-destructive) ways. In all of these films, the human characters ultimately prove more dangerous to one another than the flesh-eating zombies.

This theme, rooted in a bleak view of human behaviour (all the stranger because Romero always came across as an affable, cheerful man in interviews), runs through much of his other work as well. The Crazies (1973) is a harsh precursor to Dawn of the Dead, with a small town infected by a biological warfare accident which unleashes everyone’s latent tendencies towards psychosis. As the people grow progressively more insane and violent, with the government treating them unsympathetically as a public relations embarrassment, it finally becomes impossible to distinguish between the infected and the uninfected. The violence and madness are inherent in everyone.

While this vision of inherent violence is what Romero was most closely associated with, he did stray into other areas throughout his career – beginning right after Night of the Living Dead with a movie about contemporary relationships undermined by a sense of rootlessness. There’s Always Vanilla (1971) is largely forgotten, even by Romero’s fans (in fact he essentially disowned it himself), but it does hold some interest because once again it displays his skills as an editor. The film that followed the next year, Season of the Witch (1972), displays more ambition – the unkindly disposed would probably say “pretension”. Here Romero again deals with contemporary relationships, with stylistic nods to Bergman; the story deals with a middle class suburban housewife driven to distraction by boredom, who takes up witchcraft to add some spice to her life. Joan Mitchell (Jan White) is the first of Romero’s strong female characters and the film allies itself with feminism and the exploration of paganism as a positive alternative force for women seeking to shake off patriarchal constraints. Season of the Witch is more interesting than it’s generally given credit for, but its lack of commercial success led Romero to return the next year to the violent nihilism of Night with The Crazies.

That film didn’t fare very well at the box office either and it was five years before he made another feature. But this time he created his masterpiece. Martin (1978) is a meditation on the figure of the vampire, which Romero explores from multiple directions – a mythical monster; a manifestation of religious dread; the romantic blood-sucker of popular culture which evolved from Bram Stoker’s Dracula through various cinematic iterations; and finally a very real manifestation of psycho-sexual derangement. Romero weaves these threads together in the story of Martin (John Amplas), a young man who arrives in a dying town to live with his Old World cousin Cuda (Lincoln Maazel). Cuda is steeped in religion and superstition, believing that Martin bears a family curse; Martin provokes him by playing to that delusion, and yet in reality he does have a compulsion to drink blood, which he drugs women to obtain, slicing open their veins with a razor blade to drink from their wrists. Martin’s tragedy is that no one takes his actual sickness seriously, pushing him to play the part of the legendary monster.

Martin is Romero’s most sophisticated film, its themes reinforced by stylistic play (Martin’s vicious attacks are intercut with black-and-white images from a faux classical vampire film in which his victims desire the monster’s embrace); as the various threads draw together, trapping Martin helplessly in the role others have imposed on him, the film reaches a conclusion which is both ironic and tragic.

This time Romero got some good reviews, but still couldn’t crack the mainstream; made on a shoestring, Martin didn’t earn much at the box office. And so once again, he returned to that vision of a society torn apart by violent conflict. Dawn of the Dead was his biggest success, despite appalling the delicate sensibilities of many critics. The satire was more apparent, adding gruesome comedy to the physical horror. And yet once again, it appeared that Romero himself still wanted to resist the role his growing audience wanted to impose on him. He followed Dawn with his most personal (and to date most expensive) film and, as such things tend to be, it was something of a folie. Knightriders (1981) is a contemporary epic about idealism and nobility and the desire to live a meaningful life against the pressures imposed by materialism. Romero retells the story of Arthur and his knights through a group of bikers who travel from town to town putting on displays of motorized Medieval combat. The leader, Billy (Ed Harris in his first lead role), struggles to maintain his integrity against the pressure to commercialize, resulting in conflict with his friend Morgan (Tom Savini), who wants to cash in.

There’s an endearing absurdity to Knightriders, a naivety nowhere apparent in the rest of Romero’s movies – here perhaps we see most clearly in the work the affable man of the interviews. But despite its oddity and, again, lack of commercial success, Romero managed to score almost triple the budget the following year for his first collaboration with Stephen King. Unfortunately Creepshow (1982), a Tales From the Crypt-style anthology, while mildly amusing, has very little of the personality which came through in all the previous films. By this point it had become clear that what made Romero a distinctive artist was not something which held much interest for the industry.

Even though he was now firmly associated with the zombies, which apparently had some commercial value, he couldn’t raise the money he needed for his projected epic third part of the Dead trilogy. With less than half the budget of Creepshow, he had to scale back his plans for Day of the Dead (1985). And yet he managed to make one of his finest films. A group of scientists working to find a cure for the zombie plague are stuck in a bunker attached to a vast maze of underground caverns, where they are guarded by a group of soldiers who have no respect for the civilians nor interest in their work. While the lead scientist undertakes more and more extreme experiments – rather than looking for a cure, he’s more interested in taming and training the dead – the soldiers, faced with the total collapse of civilization, drift towards fascism. After the gaudy mayhem of Dawn, Day was too bleak for many of Romero’s fans; in tone it’s much closer to the original Night of the Living Dead than to Dawn.

Over the next fifteen years, Romero made only three-and-a-half features, none of them among his best work – Monkey Shines (1988), half of Two Evil Eyes (1990; Dario Argento directed the other half), The Dark Half (1993), and Bruiser (2000). And yet, as it became more difficult for him to get backing, his influence on the genre grew rapidly, both in the proliferation of graphic gore and the presence of zombies. Others were making more money than he ever did, often with movies far less original than his. Ironically, when he finally returned to his zombies in 2005 with Land of the Dead (which was closer to his original conception of Day than the film he had managed to make in 1985), he didn’t get a lot of respect, with many complaining that he was simply reworking old material which others had already taken in new directions (like Danny Boyle with 28 Days Later [2002]). But Romero nonetheless ended his filmmaking career with a second zombie trilogy which was far from a stale retread. His commitment to his themes and the craft he brought to these films raise them above the level of so many movies which only existed because of his example.

*

This week, following his death, George A. Romero has received a lot more press than he was afforded when he was struggling to make his movies. In one article in the New York Times, offering comments on five of those films, links were provided to the original reviews published in the Times. Not surprisingly, they were mostly dismissive – largely because horror itself wasn’t given much respect. But these reviews also tended to dismiss his filmmaking abilities, deeming them crude and barely competent. Janet Maslin, in writing a few paragraphs about Dawn of the Dead, actually starts by saying that she only watched the first fifteen minutes and then proceeds to trash the film; as a critic, she obviously felt that she could judge the whole (and Romero) without actually having to see it. Although the graphic effects are still shocking, at least now his considerable skills as a director and editor are more likely to be recognized.

*

July 26, 2017: By a strange coincidence, just a week after his death, Arrow Video announced a dual-format box set to be released on October 23 called George A. Romero: Between Night and Dawn, which includes those three early features which came between Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead – There’s Always Vanilla, Season of the Witch and The Crazies – in new hi-def restorations from original elements. Each film gets a commentary, along with new and archival interviews and featurettes (I’m particularly looking forward to a conversation between Romero and Guillermo Del Toro covering Romero’s entire career).

Comments