Twilight Time goes West

The western, perhaps more than any other genre, is shaped by a limited number of well-defined themes. The contrast, and conflict, between wilderness and “civilization”, with the former represented by native Americans and anti-social white outsiders – explorers, outlaws, men (almost always men) who have left society behind for some reason and may or may not fight their way back through some kind of noble self-sacrifice – while the latter are represented by towns, stage lines and railroads, but also by rapacious ranchers who frequently represent the darker side of westward expansion.

Gradually in the ’50s an awareness of the genocidal underpinnings of that expansion began to creep into movies like John Farrow’s Hondo (1953), with a recognition of white crimes and the justification for native resistance … but that recognition was also often coloured by a kind of resignation, a belief that the erasure of the indigenous population was inevitable and all-but-already complete. And in the same period, with the psychologization of the western hero – or anti-hero – the dark side of Manifest Destiny became internalized.

By the ’60s and into the ’70s, when turbulent conflicts began to roil society with the struggle for Civil Rights and growing resistance to the Vietnam War, the once heroic myth of the “taming of the West” came in for some radical revisionism. Interestingly, this was more likely to be a veiled attack on America’s involvement in the war, rather than a deeper rethinking of the crimes of the past – movies like Soldier Blue (Ralph Nelson, 1970), Little Big Man (Arthur Penn, also 1970) and Ulzana’s Raid (Robert Aldrich, 1972) became allegories of Vietnam.

But there had also always been westerns which ignored the conflict between whites and natives, movies which made the tacit assumption that the West was indeed an empty space waiting to be filled, and that the conflicts which arose there were white-on-white – from High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952), Shane (George Stevens, 1953) and any number of movies about Jesse James, Billy the Kid and their ilk, on up to The Wild Bunch (Sam Peckinpah, 1969), not to mention many spaghetti westerns. This reduced the larger historical narrative of conquest and subjugation to the preferred story of an internal conflict between individual and community.

Twilight Time has recently released three movies on Blu-ray which reflect these conflicts within white society in the West, spanning two decades from the early ’50s to the early ’70s. The first two were directed by old Hollywood hands, the third by an upstart foreigner making his first American feature.

Gun Fury (Raoul Walsh, 1953)

Raoul Walsh was one of those rugged male directors whose work was central to American studio movie-making. His career spanned from the early teens to the mid-’60s and encompassed most genres from comedy to melodrama, swashbucklers and historical epics to war movies and gangster films … and many westerns. He made one of the first widescreen movies, The Big Trail (1930), which features John Wayne in his first starring role; he also made the signature gangster movies The Roaring Twenties (1939), They Drive By Night (1940), High Sierra (1941) and White Heat (1949), which between them gave Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney some of their finest roles.

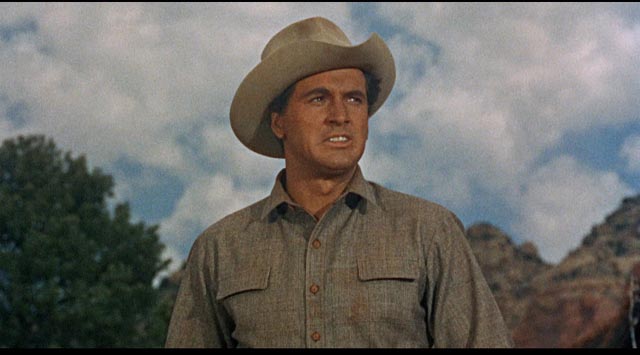

Gun Fury (1953) was not a major film for the prolific director (one of twenty he made in the ’50s), but it is marked by the level of craft to be expected of someone with his experience. The story has pace, the landscapes are used well to provide an impressive background for the action, and the cast features a good mix of stars and character actors, including early appearances by Lee Marvin and Neville Brand. Like many westerns, Gun Fury begins on a stagecoach traveling through an arid landscape dominated by imposing mesas. Among the passengers are former Union soldier Ben Warren (Rock Hudson) and his bride-to-be, Southern belle Jennifer Ballard (Donna Reed). Their fellow passengers are a pair of polite men who nonetheless suggest some vague sense of menace, Frank Slayton (Philip Carey) and Jess Burgess (Leo Gordon). At a rest stop, we discover that these two fought on the side of the South and now feel stateless.

Jess tries to persuade the couple not to continue West on the stage but to take a detour to the South. They ignore his suggestion and the next morning re-board as the stage is joined by a unit of cavalry which is to escort them through hostile territory. But it turns out that these are actually members of Slayton’s renegade gang; out on the trail, they rob the stage, killing the driver and apparently killing Ben. Rather than abandoning Jennifer, Slayton decides to take her along, a decision which triggers conflict between him and Jess..

Needless to say, Ben was only winged by the bullet and when he comes to, he sets out to find the gang and rescue Jennifer. He finds an unlikely ally in Jess who he finds tied to a fence post and left to die by Slayton. As they follow the gang’s trail towards Mexico, Ben tries to enlist help in the towns they pass, but no one is willing to risk their lives … including local law officers. The concept of law and order is fragile this far West. They are eventually joined by Johash (Pat Hogan), a lone Indian who has followed them in order to kill Jess, whom he recognizes as a member of the gang who murdered his family – the movie’s only reference to the fate of native Americans. Ben persuades Johash that Jess isn’t the bad guy, and the three continue the pursuit.

Through a series of double-crosses and personal betrayals, the gang is inevitably destroyed and Ben and Jennifer are able to continue on their journey to California and the ranch he has there beside the ocean.

Not surprisingly, it’s the bad guys who are most interesting. While Ben is a bland, conventional hero, Slaydon and Jess are bitter about the loss of their world in he Civil War, which they view as the “noble cause” (no mention of slavery, of course, as there seldom is in westerns which feature displaced southerners). They have turned to outlawry as a kind of right, a way to continue their opposition to the government. In Jennifer, Slayton sees a symbol of that lost world and by possessing her hopes to recapture something of what he’s lost. But her presence ruptures the friendship between him and Jess. In her liner notes, Twilight Time’s Julie Kirgo suggests that there is a homoerotic bond between the two men and that the split occurs as a result of jealousy, with Jess seeing the woman as a romantic rival. I’m not sure that I buy that, but there is no denying that what happens between the two men after she shows up is rooted in some deeper emotional soil than a mere disagreement about whether they should take her along.

The cinematography of Lester White uses 3D effectively, making the most of landscapes which provide natural depth from foreground scrub to distant mesas and mountains. Early on, there are several shots from the top of the stage, looking over the horses to the track ahead which runs through dips and over rises, creating an effect something like a rollercoaster. Later, as the characters get into fights, there are some excellent poke-in-the-eye moments as rocks and branches are thrown directly at the lens, eliciting some startled ducking on the couch from me and my friend Steve.

The image on Twilight Time’s disk is quite grainy, at times almost muddy, with slightly muted colours, but the 3D is effective, adding some interest to the story. (By the way, like fellow-3D director Andre De Toth – House of Wax (also 1953, a big year for the format) – Walsh was blind in one eye and thus unable to see the real world in depth.)

*

Hour of the Gun (John Sturges, 1967)

By the mid-’60s, even a fairly routine studio western might suggest a revisionist approach to a familiar narrative. In the case of Hour of the Gun (1967), director John Sturges was revising his own classic Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), which along with John Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1946) enshrined the view that the legendary showdown was between upright representatives of the law and bad men who threatened the advance of civilization in the wilderness. Sturges’ second go at the story, scripted by Edward Anhalt, complicates the legend by hewing closer to the facts – while the Earp brothers represented the law, they were also targeted by other representatives of the law. Town, state and territorial jurisdictions overlapped, each faction tied to powerful interests which were vying for control of the territory. Apparently each side in this fight carried warrants for the arrest of the other.

While the earlier movies built towards the climactic gunfight, Hour of the Gun opens with the fight and then traces the consequences. Wyatt (James Garner), his brothers and supporters face trial for murder – charges which are dismissed by the court for lack of convincing evidence. Ike Clanton (Robert Ryan) has tense meetings with his men about what to do next, and what follows is a series of ambushes and revenge killings which erase any idea of righteousness on either side. Here, as they move West, the white settlers bring along their corrupt politics, dressing self-interest in high-toned assertions about the rule of law. The myth of rugged individualism and limitless potential on the frontier is exposed as a cover for nothing more than greed.

Like many “true stories”, the movie has a fairly shapeless narrative, more an accumulation of incidents than a satisfying dramatic trajectory. By the time Wyatt pays his final visit to Doc Holiday (Jason Robards), dying of tuberculosis in a Colorado sanatorium, there’s an air of futility; all the killing has really accomplished little and the world is moving on despite the efforts of Wyatt and Ike to impose their will on events.

Sturges was rarely an exciting director, a craftsman rather than an artist; his work (particularly from the early ’60s on) was often rather stolid, even ponderous. Hour of the Gun is well-staged but never terribly exciting. Much of its interest resides in the cast – particularly a supporting roster packed with fine character actors: Albert Salmi, Charles Aidman, Steve Ihnat, Michael Tolan, William Windom, Lonny Chapman, Larry Gates, William Schallert, Monte Markham and even a young Jon Voight give texture to both sides as well as the community of Tombstone over which they’re fighting.

Robards gives Doc Holliday a mixture of gravitas and wry humour, while Ryan brings his natural world-weary authority to Ike. For me, the weak spot is Garner as Wyatt Earp. Garner had a great deal of charm, but was more at home in lighter, more comedic roles. Here he seems to lack the requisite weight to convince as a morally compromised killer whose actions are propped up by a veneer of legal authority.

The photography looks fine on Twilight Time’s Blu-ray, but under Sturges’ direction Lucian Ballard’s work lacks the dynamic energy he brought to The Wild Bunch just two years later.

*

Lawman (Michael Winner, 1971)

I’ve pointed out a number of times before on this blog that Michael Winner was a better director than he’s generally given credit for. The problem is that he had his biggest hit with Death Wish (1974), a movie which, apart from being far from his best, was seen as irresponsible and unsavoury in its seeming advocacy for armed vigilantism. The widespread condemnation of the film at the time tarred Winner himself as a crude and irresponsible person. And yet, through the ’60s and early ’70s he made a series of interesting and well-crafted movies in a number of genres. From the noirish West 11 (1963) and The System (aka The Girl-Getters, 1964) through the comedies You Must Be Joking (1965), The Jokers and I’ll Never Forget What’s’isname (both 1967), he proved an insightful observer of English life and character. Following the latter of these, he moved into international production with Hannibal Brooks (1969), an offbeat war film about a soldier and his elephant, and The Games (1970), about Olympic marathon runners.

And then he went to the U.S., looking for escape from the constraints of Britain’s faltering industry. Perhaps most surprisingly, he immediately plunged into the most American of genres, the western. Winner and his scriptwriter Gerald Wilson (who wrote five features for the director) had obviously done their homework. Lawman (1970) is steeped in familiar western tropes, but viewed obliquely with an outsider’s critical eye. On its surface it looks much like a standard western, but underneath there are cynical currents which edge towards nihilism. (Like Wilson’s script for Chato’s Land, this one takes the time to allow the characters to talk through their situation as they try to decide what to do.)

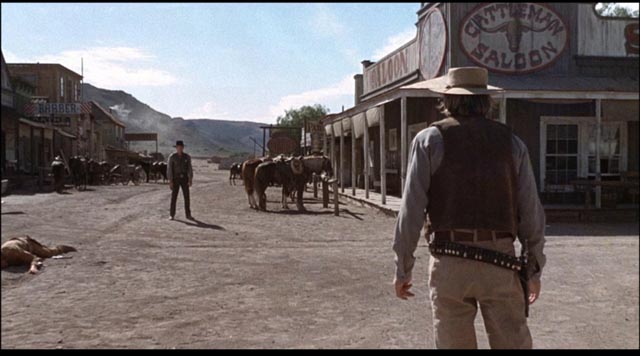

The film opens at night in the town of Bannock as a bunch of rowdy, drunken ranch hands leave a saloon and shoot up the street, smashing windows and whooping it up. As they ride out of town, the camera pans down to an old man lying against a boardwalk, dead from a gunshot. In another town called Sabbath, a stoic lawman, Marshal Jared Maddox (Burt Lancaster), rides in with a body draped over the saddle of a second horse. The dead man has relatives in town, but Maddox is unconcerned. He visits the local marshal, Ryan Cotten (Robert Ryan), with a list of names, men he says he’s going to take back to Bannock to face a murder charge. It turns out these men all work for the biggest landowner in the region, Vincent Bronson (Lee J. Cobb). Maddox doesn’t care; these men must face the consequences for killing an old man during their drunken carousing.

Cotten rides out to Bronson’s ranch to let him know. The rancher thinks it’s unreasonable to make a big deal out of what was just an “accident” and offers to pay restitution. Cotten says he doesn’t think Maddox will compromise. He’s right. Maddox believes in the rule of law with inflexible conviction. There are a series of run-ins with Bronson’s men, none of whom is a match for Maddox. When Bronson’s right-hand man Harvey Stenbaugh (Albert Salmi) dies in a gunfight with Maddox, there’s no going back; Bronson, a businessman who believes in laissez-faire and money as the universal solution to all problems, is shattered by the death of his old friend and, in spite of his desire to fix things with cash, he’s drawn into a fight to the death with the implacable lawman.

The initial situation might have been resolved easily if the ranch hands had returned with Maddox; the death of the old man was the result of careless arrogance, negligence rather than murder. But the refusal to submit to Maddox escalates the situation; the lawman becomes a de facto executioner meting out summary justice. But his rigidity gradually deforms him; the idea of the law fades away to be replaced by a kind of megalomania – Maddox, initially viewing himself as a righteous man, becomes virtually addicted to the killing until he reaches the point at which he can cold-bloodedly shoot a terrified, fleeing man in the back.

Lawman sees the West as a place where normal human relations become irredeemably distorted by the presence of guns; law and order don’t stand a chance because all conflicts lead to a point where one man feels compelled to kill another. In the traditional western this is viewed as a matter of individual strength and clear distinctions between the righteous and the bad. In Lawman those distinctions vanish; the law of the gun erases righteousness.

Winner, working for the third of ten times with cinematographer Robert Paynter, has a good eye for the western landscape and the dusty streets of a frontier town. He also exhibits his strength in casting; Lancaster brings his natural authority to Maddox’s increasingly destructive rigidity; Cobb is equally good as a man who has attained what he wants and has no interest in ruining it with the kind of armed conflict he believes belongs to a wilder past; and Robert Ryan adds his signature portrait of compromised masculinity as the marshal who is unwillingly caught between the two of them. And the supporting cast overflows with distinctive performers: Robert Duvall, Sheree North, Albert Salmi, Richard Jordan, John McGiver, Ralph Waite, John Beck, J.D. Cannon, Lou Frizzell, John Hillerman, Joseph Wiseman, Wilford Brimley … it’s like a throwback to the great days of the studios and their stables of contract players.

*

The Crimson Kimono (Samuel Fuller, 1959)

Moving further west (though not a western) and ahead in time, another of Twilight Time’s recent releases deals with racial conflict in modern Los Angeles. Sam Fuller’s The Crimson Kimono (1959) is one of his messiest films – in fact, there are moments when his directorial intentions are quite unclear – but it offers an interesting treatment of the Nisei community just a decade and a half after World War Two. While it begins as a murder mystery and police procedural, it slips into melodrama about a romantic triangle which (in case you’ve forgotten about the mystery altogether) eventually gets resolved as the case is closed right at the end.

Fuller, always willing to take a sledgehammer to any subject which engaged him, returned to racism a number of times during his long and rocky career: Run of the Arrow (1957) and Shock Corridor (1963), for example, and most explicitly White Dog (1982). Interestingly, like Shock Corridor, The Crimson Kimono deals with the internalized racism experienced by someone who has been subjected to prejudice – in the former, a Black asylum inmate, and in the latter, a Japanese-American policeman.

The movie opens with a signature crass sequence in which a stripper, dressed in her skimpy stage outfit, is pursued by an unseen assailant through downtown Los Angeles, finally shot down in the middle of traffic. Put on the case are partners Detective Joe Kojaku (James Shigeta) and Detective Sergeant Charlie Bancroft (Glenn Corbett, later star of Fuller’s Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street), who have remained close buddies since serving in the war together. In a typical overdetermined Fuller detail, they literally share blood as a result of a battlefield transfusion; and they also share an apartment, although there’s no suggestion of even a repressed homosexual relationship. The important thing is that Joe’s race appears to be a non-issue between them.

In the course of the investigation, they encounter a young art student, Christine Downs (Victoria Shaw, who the same year co-starred in Don Siegel’s Edge of Eternity). She’s the one person who may be able to identify the killer and when the sketch she makes for the cops is published, she becomes a potential target. Charlie is attracted to her and quickly builds a romantic fantasy for the two of them; but something deeper begins to form more slowly between Christine and Joe, who is a quieter, more sensitive soul who responds to her art in a way which draws her to him. When Joe finally confesses this to Charlie, he immediately interprets Charlie’s response in racist terms, rather than as the reaction of a romantic rival. He projects his own insecurity about being an outsider in American society onto his friend, fracturing the bond between them.

While all this seems psychologically valid, there’s something a little disconcerting about the way it plays out in the movie. In essence, Joe – the Other – inflicts prejudice on himself and needs to be taught by tolerant white folks – Charlie and Christine – that he does have worth and is an equal. The world Fuller depicts, complete with sympathetic treatments of Nisei culture (the story unfolds against the backdrop of a big festival in which the two buddies participate) and history (one sequence takes place in a cemetery for Japanese soldiers who died in the war serving in U.S. forces), seems to be devoid of racism. The only prejudice we see is what is conjured up by Joe’s insecurity.

On a filmmaking level, this is one of Fuller’s roughest features. There are times where the editing seems to be pointing in a particular direction, only for that trajectory to peter out into nothing. At one point, after an interview with Mac (Anna Lee), an alcoholic artist who’s also a friend, there’s a lengthy stretch of intercutting between her drinking herself into a stupor and Joe wandering around his apartment doing the mundane tasks of someone getting ready for the day. Given Mac’s tangential connection to the case, I was anticipating that the killer might be lurking about preparing to dispose of her … but that air of tension simply disappears as Fuller abruptly moves on to the next scene. The visual syntax simply doesn’t pay off and you’re left feeling that he just put in a couple of minutes of padding.

The investigation mostly disappears for a long stretch as the focus narrows to Joe’s emotional struggle and the misunderstanding between him and Charlie, but with the climactic discovery of the killer’s identity and confession of motive, Fuller finally brings the two streams back together – Joe learns that jealousy and the projection of unfounded motives onto others can only lead to pain and even violence. Rather too quickly, he gets over his self-inflicted misery and the movie suggests that everything will be fine between him and Christine in the future, though there is a suggestion that his relationship with Charlie will no longer be the same.

Despite the crudeness of the narrative construction, The Crimson Kimono is fascinating for the glimpse it provides of a community underserved by Hollywood. There’s a gritty use of locations (nicely shot by veteran cinematographer Sam Leavitt) and a refreshing interest shown in the activities of the Nisei community. Perhaps not surprisingly the movie’s trailer, included on the disk, is far less sensitive than the film itself; it loudly and melodramatically asks what this Japanese man’s unnatural interest in a white woman is? … deliberately reinforcing the idea of the menacing Other which the entire movie is working to dispel.

Comments