The storytelling art of Sadao Yamanaka

Film history is full of frustrating losses – Erich von Stoheim’s Greed, Orson Welles’ cut of The Magnificent Ambersons, and any number of other famous films which have disappeared or been mutilated along the way. But it’s not just the movies; there are filmmakers who had great promise, produced notable work, but then died young – Jean Vigo was only twenty-nine when he died, yet he left two masterpieces, Zero de Conduit (1933) and L’Atalante (1934); F.W. Murnau had made more films, twenty in fact, but was at the height of his powers when he died in a car crash at age forty-two.

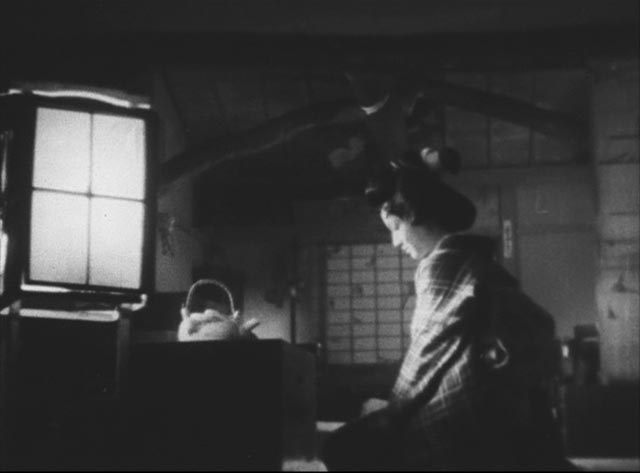

In some ways the loss is greater with the Japanese filmmaker Sadao Yamanaka. Remarkably, he made twenty-seven features between 1932 and 1937 before being drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army and sent to China, where he died from illness on September 17, 1938, at the age of twenty-eight. Whether because of Allied bombing or simply studio neglect, all but three of Yamanaka’s features are lost. Yet the three which still exist are among the greatest works of Japanese cinema from the ’30s and it’s not hard to believe that Yamanaka would have been as great a filmmaker as Naruse, Ozu, Mizoguchi and Kurosawa if he had lived to continue his work.

That said, I’m embarrassed to admit that, although I first saw Yamanaka’s final feature, the superb Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937), more than ten years ago when it was released on Region 2 DVD by Masters of Cinema, I somehow hadn’t got around the watching his other two remaining films even though I’ve had the Masters of Cinema edition of The Complete (Existing) Films of Sadao Yamanaka since it came out in 2013. But when I recently had friends over for dinner and a movie, I put that DVD in the small pile for them to choose something from and we ended up watching Tange Sazen: The Million Ryô Pot (1935), his sixteenth feature and the earliest one to have survived.

The story uses a plot device to link together a number of disparate characters. The Shogun once gave a plain clay plot decorated with a couple of monkeys in relief to one of his retainers; that retainer in turn gave it to one of his retainers, who then gave it as a family inheritance to his younger brother. The brother is embittered that all he got was this ugly and worthless artifact, and his wife sells it to a scrap dealer, who gives it to his young son to keep goldfish in… The scrap dealer wastes his time gambling and ends up being killed, his orphaned son eventually being taken in by the woman who runs the gambling house and her companion, a one-eyed, one-armed ronin named Tange Sazen. Meanwhile, it turns out that the pot actually contains a clue to a vast treasure and the original owner is trying to track it down…

This intricately structured plot is used to support not only a portrait of the multiple layers of the highly stratified society of the time – with obvious sympathies for those near the bottom and disdain for those higher up who oppress them – but also, and more importantly, a depiction of the bonds which sustain the impoverished through mutual support.

With much of the action taking place in the gambling house, the film is structured by a pattern of repetitions with variations, each occurrence featuring a musical interlude with the proprietor playing the shamisen and singing, the music serving as a creative anchor for the characters’ insecure lives. Through these repetitions, we see the orphaned boy gradually incorporated into, and reinforcing, an ad hoc family, drawing the fractious proprietor and the bad tempered, hard-drinking ronin together in mutual affection around the boy. For these people, the pot and the mythic treasure are irrelevant; it’s their human connections which matter.

Stylistically, the film declares itself as innovative and assured from the first moments. It begins with images of the natural world as a voice fills in the background about the pot, a montage which ends in the residence of the retainer originally given the pot, where we discover that the story is being told to him by an old man, forcing a sudden adjustment in the viewer’s relationship to what we’re seeing as what seemed an extra-diegetic device (the voiceover narration) turns out to be part of the narrative space – a device which is repeated immediately with another voiceover bridging a servant’s journey to retrieve the pot from the younger brother, which turns out to be that servant speaking to the brother.

This manipulation of narrative perception runs throughout the film, with playful variations undermining what would conventionally be the authority of the ronin Tange Sazen. (The film was third in a series about the character, based on a series of novels, and the original author disassociated himself from it because he disliked what Yamanaka did with the character.) Yamanaka edits very tightly, with abrupt transitions often used for comic effect; The ronin will forcefully refuse to comply with the proprietor’s demands only for the cut to reveal him doing exactly what she has asked. The storytelling is economical, without extraneous detail, propelled by a sometimes quite radical use of ellipsis which keeps the audience alert to connections which are not spelled out. This gives it a freshness which belies the film’s age.

Naturally, after this I had to watch the final movie in the set, Kôchiyama Sôshun (1936), which again takes place in that world of the lower ranks of society under the Shogunate, but is much darker than the earlier film. Once again, the plot revolves around an item which makes its way among a disparate group of characters – this time a valuable knife, gift from a lord to a retainer, which is stolen and sold, its loss placing its owner in a desperate situation; because it was a gift from higher up, its loss threatens to disgrace both its owner and his master, with seppuku almost certain to be demanded.

The knife is stolen by the irresponsible younger brother of a young woman who has a small sweet saki booth in the market. He hangs out with gamblers and has ambitions to become a gangster, while she struggles to maintain some kind of decency. As the consequences of the boy’s act ripple out to connect multiple characters, tragedy begins to close in; lives are ruined, there’s a suicide, the sister is faced with having to sell herself into prostitution to make amends for the boy, while several men try their best to help her, their concern in turn triggering other betrayals, leading to bloody conflict and the sacrifice of lives.

Kôchiyama Sôshun, made with the same kind of economy as Tange Sazen, is very much like one of Zatoichi’s adventures, existing in just the same kind of world, but here without an invincible hero to save the characters. The rash act of a thoughtless boy destroys many lives.

These two films reveal Yamanaka’s sensitivity to character, firm grasp of cinematic storytelling and deep affection for the people who live lives of struggle under an oppressive social system – all things which reach their apotheosis in his final film, Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937), which was released at the moment he was inducted into the Imperial Army.

Not surprisingly, the quality of the surviving prints is quite rough – scratches, jarring splices, missing frames and problematic audio tracks – but the transfers are all watchable. The set includes a silent extended scene from Tange Sazen (2:05), two brief clips (with introductions) from lost features which were preserved in 9.5mm home viewing versions (both energetic swordfight scenes) (5:02), and a brief account of Yamanaka’s life and career from critic and historian Tony Rayns (23:33).

Comments

These all sound interesting. Rather than jump at buying the DVDs I checked and all are available on YouTube, with English subtitles. I chose to download them and get subtitles from the subtitle sites out there. Works fine with VLC player. It’s not something I’ve done much of but the 2015 Japanese adaptation of Murder On The Orient Express turned up without subtitles from a friend. Fixed with the help of the internet. There wasn’t a DVD release when I saw it. I see someone in Malaysia is selling one but they aren’t taking payments. Not a good sign. That was on eBay.

The copies of the three older movies on YouTube probably aren’t as good as the DVDs but I can check them out and see if I liked them well enough to buy them. Always too many choices to buy everything at once.

I had to download subtitles for a German movie I had on disk years ago, ripped the disk and then reburned it with the subs. It was a bit glitchy, but the only way I could actually watch the movie and know what was going on. Haven’t done it since, though.