Michael Powell’s A Matter of Life and Death (1946): Criterion Blu-ray review

Michael Powell was, paradoxically, both a very un-English filmmaker and perhaps the most English filmmaker of all. His un-Englishness resided in what was considered during his productive years a visual excess which, if it didn’t actually plunge headlong into tastelessness, at least bordered on it. In his colour films, the colours are so rich and intense that they seem fantastical. In most of his films, the naked expression of deeply personal emotions is the kind of thing the English would rather look away from. English culture has long prided itself on restraint, on the privacy of personal feelings. Repression has typically been its method – which in itself has produced intensely emotional artistic experiences; think of David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945) or James Ivory’s Remains of the Day (1993), films which dissect this imposed reticence and the torment it inflicts on ordinary human interactions, while skirting a kind of self-congratulatory pleasure in enduring the suffering.

But Powell had no time for stiff upper lips and quiet suffering; he reveled in the power of emotions, creating works of operatic abundance which embraced a kind of ecstatic joy. In English cinema, only Ken Russell has equaled this lack of restraint, and like Powell, Russell too was often charged with tasteless excess. Both very un-English, yet arguably the two greatest English filmmakers; and both suffered opprobrium for their greatest works – Russell for The Devils (1971) and Powell for Peeping Tom (1960).

Despite so determinedly going against the grain, however, Powell was also deeply in tune with English history and, more particularly, the spiritual energies which permeate the landscape and shape the people who inhabit it. This aspect of his personality and work is most clearly visible in a triptych of masterworks he made towards the end of World War Two. These three films offered a summing up of English history and character and pointed towards post-war developments rooted in that history, developments fuelled by the ancient power of the land as it worked to forge a new world transformed by the war yet nonetheless in continuity with the history which preceded it.

The first of these was A Canterbury Tale (1944), a film set in the contemporary world overshadowed by the war, but in its deliberate harking back to Chaucer, summoning up mystical undercurrents which flow through and affect the lives of its pilgrim characters, providing both the strength and the justification to endure the war and hope for a better world nonetheless rooted in the past. This was followed by I Know Where I’m Going! (1945), a film in which the disruptions of the war years have both liberated and unmoored a young woman named Joan Webster (Wendy Hiller); no longer bound by social convention, she embraces a materialistic view of the world as she heads North with practical calculation to marry her wealthy fiance. But the forces of nature and history interfere with her journey; a storm prevents her getting to the fiance’s island and she is impatiently stranded in a small village where she meets and, against her instincts, is gradually drawn to Torquil MacNeil (Roger Livesay), a man very much attuned to the energies of the land and sea. Nature itself strives to awaken Joan and reconnect her with spiritual roots which have been severed temporarily by the war.

I’ve emphasized Michael Powell so far because these works are so intertwined with English history, landscape and culture, but all his films from The Spy in Black (1939) to Ill Met By Moonlight (1957) were made in symbiotic collaboration with the Hungarian emigre writer Emeric Pressburger, with whom he formed the production company The Archers in 1942 for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing, the first of their features to bear the unusual credit “Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger”. That film, like the previous year’s 49th Parallel, was a well-crafted piece of wartime propaganda. It was the next year that their joint creativity really declared itself with The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), a large scale Technicolor epic spanning from the Boer war to World War Two, the decades seen through the eyes of a dashing young officer who gradually becomes outmoded as the world becomes more deadly. It covers his relationships with several women and a long friendship with a German officer which bridges national conflicts. Its theme is the toll progress takes on people and the dangers of losing connections to the past – the central idea which runs through the films which followed, that history is a kind of energy which flows through a people from past to future and the danger which arises when one becomes disconnected from the stream.

Although Powell had contributed to Alexander Korda’s opulent The Thief of Bagdad (1940) as one of three credited directors (there were three more uncredited), and despite the increasing presence of mysticism in his work, it wasn’t until 1946 that he made an overt fantasy, but one which was nonetheless rooted in contemporary experience and built on his developing thematic concerns. A Matter of Life and Death (re-titled Stairway to Heaven for the U.S. because the word “death” was considered bad box office after years of war) was the result of an entreaty from Jack Beddington, head of the film division of the Ministry of Information, asking for a cinematic antidote to the tensions between the British and the Americans which had been increasing as the war was winding down. In the hands of Powell and Pressburger this project expanded far beyond that immediate social and political concern and took on a sweeping cosmic scale, setting petty national conflicts against both eternity and the personal emotions of two ordinary people.

A Matter of Life and Death (1946)

A Matter of Life and Death is a romantic fantasy which pits the love of a man and a woman against the vast forces which have been tearing the world apart for six years, but also against a cold universal system which puts its own efficiency ahead of individual feelings. While that idea – that love supersedes all other considerations – is something of a trite commonplace, the structure provided by Pressburger’s script offers an assertion of the value of individual lives against the massive and impersonal destructive forces of the war.

After a cosmically expansive prologue which expresses wonder at the vast scale and beauty of the universe, gradually closing in on the small and seemingly insignificant speck which is Earth, the perspective shifts abruptly to something intimate and intensely moving: an RAF squadron leader, alone (except for the body of one dead crewman, the others having all bailed out) in a burning plane on its way back from a raid on Germany, makes radio contact with an operator on the ground – a young American woman who tries to assess his position and status. He confuses her by ignoring her practical questions and instead quoting poetry and asking her to telegraph his mother to say goodbye. The plane is beyond saving and he has no parachute, his only options either to crash and burn or jump to his death.

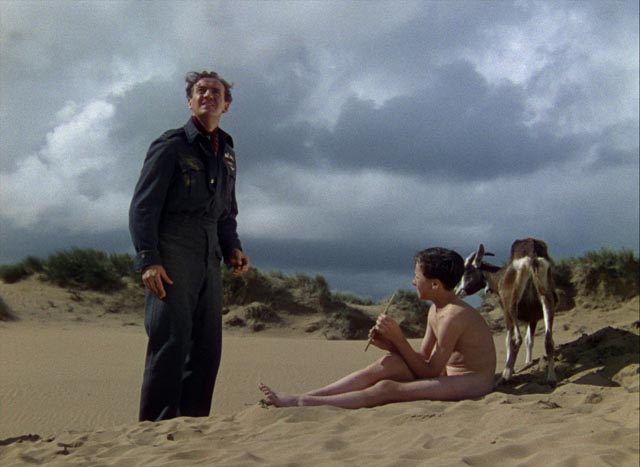

In those few minutes, they make a deeply personal connection, yet it’s one which can exist only in that single moment; he will die and there’s nothing she can do to help. Yet the next morning, the squadron leader – Peter Carter (David Niven) – wakes on a broad sunlit beach. He believes he’s dead, that this is the afterlife, and he discards his flying gear and walks barefoot across the sand. He meets a dog (and comments that he’d hoped there’d be dogs in Heaven) which leads him to a naked boy sitting on a dune playing a flute as a small herd of goats grazes nearby. Peter is asking who he should report to when a low-flying plane roars overhead. It turns out that he is not dead, and that he is in fact near the airfield he was heading for when he jumped. And just then, down on the beach, he sees a woman in uniform riding a bike and runs to intercept her.

She is of course the woman from the radio – June (Kim Hunter) – and she’s initially upset because she thinks he had somehow deceived her the night before. But he’s just as confused because he can’t understand how he managed to survive. As their romance quickly develops, strange things begin to happen to him – time freezes and a flamboyant Frenchman in period clothes arrives to tell him that he should indeed be dead, that the dense fog on the night of the crash made him miss his connection. Conductor 71 (Marius Goring) has been sent from the other world to rectify the error, but Peter refuses to go – this was someone else’s mistake and, although he had been prepared to die, he now has a very good reason to live.

The narrative proceeds on two planes – Peter’s life in a small village with June, and the authorities in Heaven trying to sort out the mess. Such mistakes are very rare and there are no established methods for dealing with them, so when Peter insists that he be allowed to appeal against the ruling that he must die, the bureaucracy is forced to bend although it is reluctant to risk him winning his case. As prosecutor, Abraham Farlan (Raymond Massey) is chosen, the first American to die from an English bullet in the Revolution. He hates the English with a passion and is appalled that a young woman from Boston should have been ensnared by this Peter Carter.

As the trial approaches and Peter has his hallucinatory encounters with Conductor 71, June’s friend Doctor Frank Reeves (Roger Livesay) deduces that Peter is suffering from a brain trauma which occurred months earlier and is causing increasingly dangerous seizures. He realizes that as the trial Peter describes approaches, an operation is essential – that his brain needs to be repaired before it effectively carries out its own death sentence. Powell and Pressburger skillfully maintain a narrative balance between the possibility that Peter’s experiences with the other world are simply elaborate delusions or, on the other hand, that they are entirely real.

The final act fuses the operation on Peter’s brain and the trial in Heaven, the latter centred on Farlan’s fierce attack on England – a nation hated around the world by the inhabitants of so many other countries which have been oppressed by the Empire. His argument essentially rests on the idea that the English can’t be trusted and that June has been duped. As Peter’s defence counsel, Frank Reeves counter-argues that – as the American Constitution asserts – individual rights must trump the rigid dictates of a law which is enslaved by an entrenched bureaucracy. Ironically, when Frank challenges the jury of men representing countries mistreated by England and demands a jury of Americans, what he gets is a collection of immigrants from those same countries, now proud citizens of the United States, plus a Black soldier from the current war – a pointed reminder of America’s own deep flaws.

A Matter of Life and Death works on several levels at once – a warm defence of romance, an expression of individual emotions as a counterpoint to the vast scale of the universe, and an argument for the shared interests of England and America in the wake of the devastation wrought by global war. That it manages all this with humour and passion is a mark of Powell and Pressburger’s prodigious creativity. But beyond the dramatic accomplishment of the film, it offers breathtaking visuals – both the intense Technicolor intimacy of the Earthbound narrative and the epically grand monochrome depiction of Heaven with its Art Deco and Modernist echoes of Metropolis (1927) and Things to Come (1936).

These visuals, designed by Powell’s long-time collaborator Alfred Junge, and photographed by Jack Cardiff (who had previously only done 2nd unit work), make A Matter of Life and Death one of the most spectacular English films ever made. Cardiff followed his work here with Powell and Pressburger’s Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948), cementing his reputation as perhaps the greatest of all Technicolor cameramen.

Powell and Pressburger keep the fantasy firmly grounded – in part by their careful handling of Peter’s illness, which is a realistically depicted form of epilepsy caused by localized damage to the brain (there’s even a book by neurology specialist Diane Broadbent Friedman analyzing the film from a medical perspective), but also through the excellent, generally understated performances. From David Niven’s dedicated officer, who is at heart a poet, to Kim Hunter’s charming, passionate yet inexperienced radio operator; from Roger Livesay’s village doctor, whose interests go far beyond everyday medicine, to Raymond Massey’s supercilious prosecutor forced to confront his own prejudices – there isn’t a false note in the film. There are detailed minor characters, like Robert Coote’s dead crewman and Kathleen Byron’s heavenly office manager whose adherence to protocol cracks when faced with the consequences of procedural error. And Marius Goring is a standout as a comic counterfoil to the romantic drama as Conductor 71, a bit of a fop who was beheaded during the French Revolution.

*

The disk

The image on Criterion’s Blu-ray is breathtaking. Restored in 4K by Sony, it required meticulous work to transfer, realign and combine the three separate Technicolor negatives, which had all undergone different degrees of shrinkage. There is very little evidence (if any) of misalignment or colour fringing, and the Earthbound images have deep rich colours and excellent contrast, while the monochrome other world is rendered in a subtle range of grays. At the time the film was made, dissolving from black-and-white to Technicolor was a difficult technical problem, but Cardiff’s superb camerawork makes it seem perfectly natural and effortless.

The mono soundtrack has clarity and depth, giving the opening plane sequence dramatic force, while Allan Gray’s score boosts the romantic mood of the film.

The Supplements

The disk contains a substantial array of supplements, beginning with a comprehensive commentary from Ian Christie (recorded for a Sony DVD edition in 2009), who argues that the film is essentially an allegorical masque, with Peter and June archetypal representatives of Love.

Martin Scorsese provides an enthusiastic introduction from 2008 (9:16), recounting his discovery of Powell’s work and subsequent friendship with the director.

In a new interview (32:38), Powell’s widow, Thelma Schoonmaker (editor of many features for Scorsese) talks about Powell and his work, her own relationship with him, and some background on the film (she mentions that the idea was rooted in an actual incident involving a pilot who survived bailing out of his plane without a parachute).

The Colour Merchant (1998, 10:20) is a preliminary sketch made by Craig McCall while he was working on his documentary Cameraman: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff (2010). It specifically covers Cardiff’s work on A Matter of Life and Death, his first full feature as a cameraman, discussing the film’s technical challenges and the origins of Cardiff’s working relationship with Powell.

There’s an interview-based featurette on the film’s special effects (31:18), with the images being explained by effects artists and historians Craig Barron and Harrison Ellenshaw (whose grandfather W. Percy Day created the many matte paintings for the Heaven sequences).

The South Bank Show: Michael Powell (1986, 54:59) is a British television documentary made to coincide with the publication of the first volume of his autobiography, in which the director reminisces about his life and work. (By the way, Powell’s two-volume memoir – A Life in Movies and Million Dollar Movie – provides one of the finest accounts of a filmmaker’s work ever published.)

A restoration demonstration (4:39) shows before-and-after images which illustrate just how drab previous editions of the film were compared to this vibrant new restoration.

The booklet essay is by Time magazine critic Stephanie Zacharek.

Comments