Giallothon!

At what point does abundance slip into overkill? One of my recent prized acquisitions is a limited edition box set (2500 copies) from Severin which is built around Sergio Martino’s supernaturally-inflected giallo All the Colors of the Dark (1972). There are two versions of the movie – a new 4K scan from the original negative for the full-length film as well as the shorter U.S. cut called They’re Coming to Get You in standard definition – plus interviews with director Martino, writer Ernesto Gastaldi, actor George Hilton and Italian critic Antonio Tentori. There’s also a commentary from Kat Ellinger and a CD of the full Bruno Nicolai soundtrack.

But what really puts the set over the top is a second Blu-ray containing a ninety-minute documentary on the giallo – All the Colors of Giallo by Federico Caddeo (2019) – plus no less than four hours of giallo trailers (dubbed Giallothon on the disk), arranged chronologically with a non-stop commentary from Ellinger who provides a dense history of the genre along with personal opinions about the individual movies represented. As if that isn’t enough, this disk comes with a separate DVD of trailers for German krimi (91 minutes), accompanied by a 24-minute interview with German film historian Marcus Stiglegger about that separate but related genre, and a third CD disk of remastered themes from multiple gialli.

In other words, the set contains enough material to choke the most obsessive genre enthusiast.

All the Colors of the Dark is considered by many to be Martino’s greatest giallo, but I actually prefer his other two Edwige Fenech-starring gialli – The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1971) and Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key (1972) – possibly because I prefer my gialli to be weird, but not supernatural. In Colors, the heroine, beset by hallucinations and confused memories, is under attack from a cult of devil-worshipers rather than a merely deranged killer.

That said, the film looks terrific here, with a flawless image. There’s an English dub along with the original Italian with subtitles. Although I have reservations about the film itself, the disk would be worth adding to my collection anyway … but what made it an essential purchase was the massive accompanying survey of the genre.

Given the cultural prominence the giallo now has (subjected to pastiche across a range from cheap exploitation [Adam Brooks and Matthew Kennedy’s The Editor (2014)] to self-consciously arty [Peter Strickland’s exceptional Berberian Sound Studio (2012) or anything by Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani]), it’s almost surprising to note that, despite a few precursors in the 1960s and a fairly long tail which tapered on into the ’80s and ’90s, it existed in its most defined form for barely five years, from 1970, with the arrival of Dario Argento’s The Bird With the Crystal Plumage, to 1975 or so. The groundwork, of course, had been laid by Mario Bava in two of his key films – The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963) and Blood and Black Lace (1964). The former provided essential structural ingredients (the unreliable witness; the roots of murder in some past trauma), while the latter established the visual language (hallucinatory colours; the masked, black-gloved killer). But the industry was slow to take up Bava’s narrative and stylistic innovations and the form wavered in the later ’60s between melodramatic mysteries focused on women in trouble and psychological horrors with the occasional serial killer thrown in.

It’s interesting to note that at almost the exact moment that Argento released The Bird With the Crystal Plumage (February 27, 1970), Elio Petri released Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (February 12, 1970). Both films have a stylized modernist visual sense, contrasting the disordered psyches of troubled characters with the formal aspects of modern architecture. Both deal with psychological derangement which seems both to grow out of and to infect these cool, somewhat inhuman environments … but Petri puts the formal elements in the service of a political critique of modern Italy, while Argento revels in the pleasures of the pulp thriller. Petri got the lion’s share of the critical accolades (including a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar), while Argento launched a popular commercial genre, but both seemed to be drawing on similar cultural and aesthetic influences.

The Italian film industry immediately took note of Argento’s achievement and very quickly pretty much every commercial (and sometimes not so commercial) Italian filmmaker tried their hand at the giallo. Of the eighty-two trailers on the disk, thirteen fall between 1963 and 1969 and fourteen between 1976 and 1983, with the other fifty-five coming between 1970 and 1975. There’s a deliberate symmetry in the selection of titles, with the compilation beginning with Bava’s two proto-gialli and ending with his son Lamberto’s A Blade in the Dark. In between we see the rise and eventual dissolution of the genre as heightened violence, psychological derangement and exploitative sexuality began to slide into increasingly disturbing and sleazy areas, eventually blending into pornographic extremes.

But extremity and excess were always crucial to the appeal of the genre. This is why, although its roots went back to more traditional mysteries, its essence was style and mood. In many gialli, the resolution – exposing the identity of the masked killer – seems almost irrelevant. What matters is the accumulation of frissons along the way, the construction of a series of creepy, unsettling sequences built around escalating feelings of paranoia and vulnerability. The best gialli were made by filmmakers who had a flair for visual style; the weaker gialli were made by more limited filmmakers who had to rely instead on visceral shocks and images and incidents whose sole purpose was to be transgressive.

Since watching Federico Caddeo’s documentary All the Colors of Giallo and the accompanying collection of trailers, I’ve been expanding my experience of the genre – more than three dozen of the movies represented were already in my collection, and I’ve subsequently found a couple of dozen more in various on-line niches, plus quite a few additional ones which aren’t included on the disk. A lot of these are movies which would have been completely unavailable to me back when I first became interested in the giallo. Now I’m almost overwhelmed by the abundance.

Although I’ve only just begun to dig in, I’ve come across a number of interesting things. As I mentioned here a while back, for a long time I had a pretty low opinion of Umberto Lenzi, based entirely on the wretchedness of his contribution to zombie cinema, Nightmare City (1980). That opinion had to be radically adjusted after seeing his crime thriller Almost Human (1974) for the first time. But I still hadn’t sought out more of his work. So I was a bit surprised to discover that, in Kat Ellinger’s account, he holds an important place in the genesis of the genre through a series of thrillers he made in the late ’60s with American actress Carroll Baker, who had moved to Italy a couple of years earlier. I haven’t yet watched Paranoia (1969), So Sweet … So Perverse (1969), A Quiet Place to Kill (1970) or Knife of Ice (1972), but I have checked out two of Lenzi’s later gialli – Seven Blood-Stained Orchids (1972) and Eyeball (1975).

Neither film displays much stylistic flair, but neither are they as crudely lazy as Nightmare City. Orchids is a fairly routine giallo in which a mysterious killer is stalking a number of seemingly unconnected women. He doesn’t have a consistent MO – he slashes, strangles, drowns and power-drills his victims – which diminishes the usually obsessive nature of the genre; and when the killer is finally revealed, his motive turns out to be very prosaic rather than an expression of deep psychological derangement.

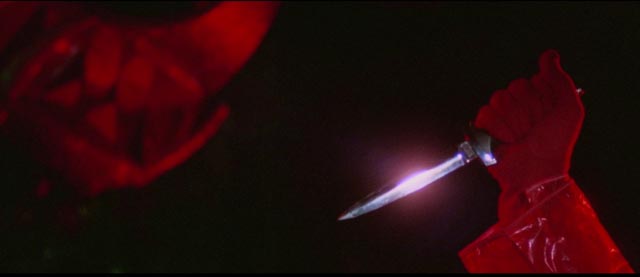

Eyeball, on the other hand, which has the American passengers on a bus tour of Barcelona getting knocked off by a killer in a red plastic raincoat (raising vague echoes of Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now [1973]), is more interesting. The murders are pushed into horror territory by the fact that the killer takes the victims’ eyes. Plausibility isn’t much of a consideration – as people die, their fellow passengers continue to sight-see around the city – but the climactic revelation of the killer’s identity and motives is quite bonkers and oddly endearing.

In My Dear Killer (1972), Tonino Valerii, a protege of Sergio Leone best known for his spaghetti westerns (including two of that genre’s best: Day of Anger [1967] and My Name is Nobody [1973]), displays a more polished style than Lenzi, working with a narrative closer to classical mystery than outright giallo. But while the story – a cop investigating the brutal death of an insurance investigator finds the clues leading back to the kidnapping and death of an industrialist and his young daughter, with a killer keeping one step ahead of him to bump off witnesses – is fairly conventional, Valerii, in his sole venture into the genre, starts things off with a very strong opening sequence which invests everything that follows with a sense of menace and potential horror. In that scene, the insurance investigator is directing the driver of an excavator to start dragging the weed-choked water at the edge of a flooded quarry; while he’s looking out over the water, the unseen driver swings the bucket with its massive metal teeth overhead and scoops the investigator up by the neck, beheading him. While nothing that follows can match the visceral power of this sequence, the narrative is tightly constructed, the clues carefully laid out, and the resolution logical.

*

Which is not something that can be said of a couple of the sleazier movies I’ve recently watched.

Fernando Di Leo is best known for his poliziotteschi, a genre in which he was very proficient, but he really fumbles Slaughter Hotel (1971). A gloved killer is stalking the halls of a remote, exclusive mental hospital which caters to wealthy women. There are delusional patients, a nymphomaniac, and other stock characters, along with a possibly sinister doctor (Klaus Kinski, no less), but the pace is glacial, the atmosphere minimal, the ultimate revelation of the killer’s identity and motive mundane … plus several graphic sexual inserts were obviously cut in by a distributor hoping to make it more saleable (a common practice at the time). It’s the worst film I’ve seen by Di Leo, and apparently he agrees: in an interview included on the Raro Video Blu-ray, he says it’s a “very bad film”.

Mario Landi’s Giallo a Venezia (1979) came late in the career of a director whose credits are mostly in television. It’s certainly not dull like Slaughter Hotel, but it has a pervasive sleaziness which leaves the viewer feeling pretty grubby. That said, it does have an interesting dual structure which initially seems quite random but eventually ties together (more or less). A dead couple are found beside a lagoon in Venice, the man savagely hacked with a pair of scissors, the woman drowned. The police are puzzled by the fact that the drowned woman has been dragged from the water and laid beside the man. Much of the movie is occupied with filling in the story of this couple and the events which led to their deaths. A married couple, they have a sadomasochistic relationship which gradually spins out of control. The husband can only be aroused by watching his wife engaged in sex with others and he pushes her into increasingly extreme and dangerous situations for his own gratification. Because she loves him, she goes along with his demands until she can’t stand it any more …

Meanwhile, as the police dig into their deaths, a killer is stalking the city, killing men and women in particularly brutal ways. While the links between these two threads are essentially tangential, the parallel structure draws pointed connections between the misogyny of the husband and that of the killer, with masculine “love” and desire rooted in an obsessive need to control and ultimately destroy the women who inspire feelings that men are supposedly unable to control in themselves.

*

So far, the big discovery arising from Severin’s Giallothon is a director named Luigi Bazzoni, whom I hadn’t previously come across. Perhaps this isn’t surprising given that he made only five features (between 1965 and 1975), plus a few early shorts and a handful of documentaries twenty years after his last feature. Of the five features, two were spaghetti westerns, with the other three qualifying as gialli if you stretch the genre’s definition a little.

Only one of Bazzoni’s films makes it into the trailer compilation, his third feature The Fifth Cord (1971), which is in some ways, I’ve discovered, the most conventional of the three. Someone is killing people in Rome and alcoholic journalist Andrea (Franco Nero) is assigned to report on the case. But he soon finds himself falling under police suspicion and has to pull himself together to solve the case and clear his name. So far, so standard. What sets The Fifth Cord apart is Bazzoni’s style. It’s as if Antonioni had made a giallo; the film is visually stunning (shot by Vittorio Storaro, Bazzoni’s cousin), situating its characters in an inhuman modernist urban landscape which evokes emotional and psychological disconnection and isolation. The violence grows out of an overwhelming sense of alienation. (The film also has perhaps the single greatest instance of the genre’s ubiquitous J&B scotch product placement – though I suspect J&B might not have appreciated it – as a despondent Andrea drives at night swigging gulps straight from the bottle, its label turned prominently towards the camera.)

After watching the film on Arrow’s excellent Blu-ray, I had to seek out Bazzoni’s other gialli. I found a passable copy of his final feature, Le orme (aka Footprints on the Moon, 1975) on-line. It’s easy to see why this is not so readily available as it pushes the hints of abstraction in The Fifth Cord to extremes. A strange, dreamy art film rather than a commercial thriller, it opens with a disconcerting title sequence in which an astronaut is deliberately stranded on the moon as part of a sinister psychological experiment conducted by a cold-blooded scientist played by Klaus Kinski. This turns out to be part of a movie called Footprints on the Moon which protagonist Alice Cespi (Florinda Bolkan, who, appearing in Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion and Lucio Fulci’s Don’t Torture a Duckling [1972] among many other movies, provides a personal bridge between Italian art and genre cinemas) saw as a child; she is haunted by the memory of it and has recurring dreams of what she saw. Her anxiety has led to an addiction to tranquilizers which affect her ability to function efficiently.

Emerging from one such dream, she discovers that she has lost three days, her absence from work (as an interpreter at an international conference) getting her fired. The only clue to the missing time is a torn postcard she finds in her apartment showing a hotel in the resort of Garma. She recognizes the image, but can’t remember why it’s familiar. Traveling to the off-season island resort, she takes a room in the hotel and discovers that various people saw her there a few days earlier, but she was using a different name. As she tries to piece things together, it emerges that this “other her” was looking for someone, someone who lived in a large house in the woods. Layers of memory peel away, leading back to a childhood experience … but by the time those memories come into focus, she has descended into a state of delusion and paranoia, unable to trust anyone as images from the old sci-fi movie begin to impinge on the real world …

Le orme contrasts the modernist city familiar from The Fifth Cord with the older world of the island and its beaches and woods; it’s as if Alice (a significant name choice?) has slipped into an alternate reality infused with undefined fairy tale menaces. She imagines monsters concealed behind friendly faces and, unable to tell who might be a friend, strikes out violently before slipping irretrievably into madness… It’s a fascinating film, but deliberately resists easy understanding. The elusive narrative is held together by Bolkan’s superb performance, but with the audience being tied so closely to her point of view as her grip on reality becomes increasingly tenuous, the story remains unresolved. Bazzoni deliberately withholds conventional narrative pleasure, creating instead a lush, oneiric meditation on the fragility of identity in a world which tries to constrain it within supposedly acceptable bounds.

As much as I liked The Fifth Cord and Le orme, I think my favourite of the three films is the earliest, The Possessed (1965), co-directed with Franco Rossellini (Roberto’s nephew) and co-written with Giulio Questi (no slouch in genre-bending himself as director of the idiosyncratic Death Laid an Egg [1967]), adapted from a novel by Giovanni Comisso reportedly based on an actual murder case. This exquisite black-and-white film is more Gothic romance than giallo, steeped in an atmosphere of doom. Writer Bernard (Peter Baldwin) abandons his current relationship and drives to a bleak, off-season lake resort, taking a room at the empty hotel he has stayed at before. He is supposedly working on a book rooted in his own past and is haunted by memories of a hotel employee named Tilde (Virna Lisi). He is shocked to learn that she has apparently committed suicide. In trying to discover what actually happened, he learns things which undermine his romantic image of the woman and reveal unsavoury facts about the hotel owner, his son and daughter. An alienated man clinging to romantic illusions, he is unable to help another troubled woman – the wife of the owner’s son – because he has a weak grasp of reality. The narrative he tries to impose on the world around him obscures other, more troubling narratives, and his misunderstandings are implicated in yet another death.

The Possessed has also been released on Blu-ray by Arrow (it would be great if they could do the same for Le orme) in an extras-laden edition which includes a number of interviews as well as a Tim Lucas commentary. The image is lovely, with finely textured wintry greys … and maybe that’s what makes me like it best of the three; I do love black-and-white!

*

Severin’s Giallothon has suggested a lot of paths to follow, but for now I’m just grateful that it has led me to the work of Luigi Bazzoni (with the corollary disappointment that I’ve so quickly seen all his films in this genre, with just two westerns to seek out before I’ve exhausted his filmography). He illustrates just how far a genre can be stretched to explore deeply personal themes, pushing what in other hands may amount to little more than trashy entertainment into the realm of art. As an explorer of existential despair and alienation, despite the genre trappings, he’s up there with Antonioni.

Comments