Cinefantastique: nostalgia for print

I was recently rooting through a stack of boxes in my mother’s basement and came across my old collection of Cinefantastique magazines. I can’t recall exactly how I first heard about it – I think it might have been a brief announcement by Baird Searles in his occasional movie column in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. But whoever it was, there was a recommendation that a worthwhile new magazine about fantasy and science fiction film was being launched, and the address and subscription information was provided. Since I loved genre films, I immediately sent off a money order and in due time Issue 1, Volume 1 arrived in the mail.

That first issue, Fall 1970 with Mike Nichols’ Catch-22 on the cover, was all black-and-white (the covers became full colour with issue #3; interior colour was finally added with Volume 2, Issue 1 in the spring of 1972). But as stark as that first issue looked, it really impressed me. This wasn’t a fun pulp item like Famous Monsters of Filmland (though I still regret the disappearance of my collection of Forrest Ackerman’s famous creation many years ago); this was actually a serious journal being published on an almost-professional level. I only learned later that publisher/editor Frederick S. Clarke had been putting out a fanzine since 1967, and the new magazine was an evolution from that. No ads for x-ray glasses and gag items here, the 48-page magazine was packed with articles, reviews, news items, all printed in very small type so as to squeeze as much as possible into its pages.

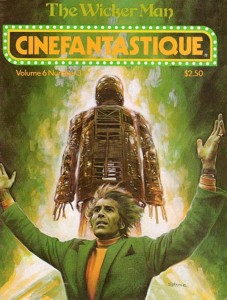

Immediately following Clarke’s opening editorial remarks, which explained his philosophy and approach – that these genre films, so often dismissed as time-wasting entertainment, deserved serious critical attention as much as any other class of films – there’s a remarkably lengthy article by Clarke himself on the history of Rasputin in movies; then a shorter piece by Robert L. Jerome about the troubled production and distribution of Joseph Losey’s The Damned (aka These Are the Damned). So there I was in the Fall of 1970, reading about a movie made in 1961 which had essentially vanished from sight. (They did it again in 1977 with their coverage of the production and fumbled distribution of The Wicker Man, a film which wasn’t easy to see until years later.) This illustrates one of the pleasures of Clarke’s magazine: the depth of the content, the ability to whet your appetite while at the same time filling you with a deep sense of frustration … here you could read about fascinating movies you’d probably never get a chance to see (in fact, I finally did get to see the Losey film maybe seven or eight years ago, a pan-and-scan bootleg VHS tape I got off eBay, which somehow seems appropriate given that first introduction in the pages of CFQ forty years ago; thankfully, it’s now easily available on DVD and I’ve watched it several times in the past year).

The review section of that first issue is also quite remarkable. It starts with Fellini Satyricon, includes Catch-22 and Beneath the Planet of the Apes, goes on with the great Colossus: The Forbin Project and Argento’s Bird With the Crystal Plumage (the former a rave, the latter not so much), there’s Jess Franco’s Eugenie, Antony Balch’s Secrets of Sex/Bizarre, and Ishiro Honda’s Latitude Zero, plus a collection of small horror B-movies. Clarke cast a pretty big editorial net, obviously determined to fulfill his promise to put out THE review of fantasy, science fiction and horror movies.

But wait, there’s more! A report from the 1970 Trieste Science Fiction Film Festival where movies like Peter Watkins’ The Gladiators and The Mind of Mr. Soames (apparently TV director Alan Cooke’s sole theatrical feature) received awards from an international jury which included the great British science fiction writer Brian Aldiss. A soundtrack review column; a piece about the development of holographic movies; little news clips from around the world; and a “Coming” section packed with tantalizing announcements about films supposedly in the works (like The Andromeda Strain, A Clockwork Orange, The Devils, I Am Legend, Running Silent [sic] …).

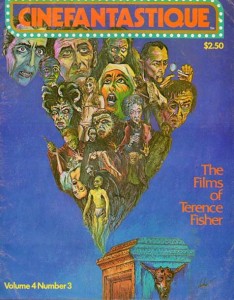

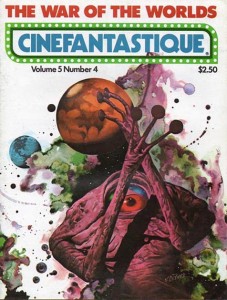

It’s probably difficult for somebody today to understand just how exciting a magazine like this was back then. Of course, there was no Internet, no home video … and no serious coverage of these genre films anywhere. Clarke did a remarkable job of raising expectations about the future of the genre while also providing terrific coverage of the past. Issue #3 contained the first of the famous CFQ retrospectives, beginning quite modestly with William Dieterle’s delicate 1948 romantic fantasy A Portrait of Jennie, followed in the next few years by detailed histories of I Married a Monster From Outer Space, Them!, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Forbidden Planet, War of the Worlds and others, as well as in-depth career interviews with and articles about figures like Christopher Lee, Terence Fisher, George Romero.

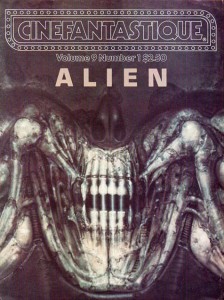

Clarke also opened up the magazine for reader response and debate, including a letters section from the second issue on. And it’s interesting to see how passionate some of that response could be (a precursor to over-heated on-line comments sections); the magazine was frequently attacked for the positions Clarke and his writers took on individual films and the genre itself, some of this simply disagreement based on personal taste, sometimes something more intense, particularly when the genre became a more mainstream phenomenon. Although the magazine devoted a lot of space to films like Star Wars (an amazingly detailed production history), Clarke expressed his reservations about the value of some of these movies as movies … and the vitriol flowed. Just like on the Internet today if someone dares to criticize or have reservations about a popular success.

It was in the late ’80s that an odd kind of tension seeped into Cinefantastique because of this dichotomy between box office success and creative limitations. The magazine gave over more and more space to in-depth coverage of big new releases, working hard to get stories ready to coincide with a film’s release (a not inconsiderable marketing concern); but this meant that quite often there would be a huge article in the same issue as a critical review of the film in question. This contradiction drove some readers crazy. But for Clarke himself there actually didn’t seem to be much of a contradiction at all: he could recognize the importance of a particular movie from a technical or commercial standpoint while still criticizing it as a film.

I continued to subscribe to CFQ for 18 years, letting my subscription lapse finally at the end of 1988, though I still occasionally bought a newsstand copy over the next few years. It seemed that the magazine had drifted more towards the mainstream as the genre itself became the most profitable at the box office. In addition there were more sources of information available by then, so CFQ no longer had that almost unique position which made it so exciting in the early years.

I only met Fred Clarke once, on a brief stop-over in Chicago on my way back from Mexico in 1983. We had lunch and I handed over a thick packet of photographs which David Lynch had given me to illustrate the retrospective article I had written for CFQ about Eraserhead. He seemed like a nice guy, and I certainly appreciated the fact that he would be publishing my work even though it wasn’t quite in the style typical of the magazine. But he took it because his appreciation of Lynch’s film was as strong as my own, so we had a connection there.

A few years after Clarke’s death in 2000, Cinefantastique ceased publishing, re-launching a year later as an on-line site. That site is quite impressive, but it can never have the same kind of impact on me as that first issue in the Fall of 1970 had.

Digging through that box in the basement has triggered a massive dose of nostalgia, but more than that, it reminded me that, in a way, I owe quite a lot to Fred Clarke and his feisty magazine. It was through them that I got to meet David Lynch, which eventually led to my six months in Mexico working on Dune, which in more indirect ways eventually influenced my career as a documentary editor.

Looking through these dozens of densely packed issues, I’m surprised at just how strong my personal feelings for this unique magazine are, and just how much we may have lost because information is so easy to come by now.

*

There’s an excellent history of the magazine written by Steve Biodrowski on the website.

Comments