Post-Op, week four

J.G. (Pat) Patterson was a regional filmmaker based in North Carolina. Although he directed two features, his importance lay more in what he did to facilitate the work of others. He was associate producer on Herschell Gordon Lewis’s The Gruesome Twosome (1967), but more importantly he was instrumental in getting Frederick R. Friedel’s first feature, Axe (1974), made. I haven’t seen Patterson’s own first feature, The Body Shop (1972), apparently a derivative gore-horror movie about a doctor trying to rebuild his dead wife using parts from murdered women. But now, thanks to Code Red, I’ve had a chance to see his second, The Electric Chair (1975), and I can confirm that his greatest contribution both to regional filmmaking and to cinema history was in nurturing the talent of Frederick R. Friedel.

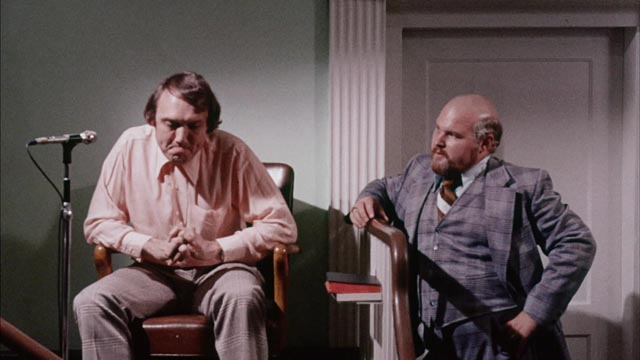

It’s not a good sign when people who worked on a movie begin their commentary track by saying this is the worst thing they were ever involved in, but that’s what we hear off the top from production assistant Phil Smoot and special makeup creator Worth Keeter, both of whom also worked on Axe. It would be difficult to disagree. To put it mildly, Patterson was very clumsy as both writer and director – although his acting does have some eccentric charm.

The Electric Chair isn’t horror, despite the marketing, but rather a mystery and courtroom drama. A local preacher and an unhappy housewife are found brutally murdered one night and the cops and the D.A. are stumped, though they eventually charge and try a deranged religious fanatic whose supposed motive is Biblical justice meted out to sinners – the couple were having an affair. The guy, Mose (played by a scenery-chewing Patterson), is convicted and eventually strapped into the titular chair with just seconds to go before the switch is thrown when the Governor calls to stop the execution. Turns out old Mose had an alibi he was unwilling to use – he was himself involved in an illicit sexual relationship and the woman finally came forward to save him by exposing his own sin. The trauma of the almost-execution plus exposure of his iniquity gets him sent to an asylum.

Facing political pressure, the D.A. has to reopen the case, digging up some eye witnesses who for some reason were previously dismissed as unreliable. They finger the preacher’s bitter, sexually repressed wife and her mentally impaired brother. Though the defense demolishes all the witnesses, the pair are convicted and the movie ends with an execution sequence which, perhaps because it’s so tawdry and matter-of-fact, seems more depressing than The Green Mile (1999).

If this description seems coherent it’s because I haven’t touched on the bad writing, the small-town rep company performances, and the wood-paneled, check-suited production and costume design … not to mention non sequiturs like a detour into a local Black jazz club featuring strippers apparently shot in an entirely different location and randomly cut in. Normal courtroom procedures are tossed out, giving testimony and cross-examinations an almost surreal quality. And the whole thing is shot with little awareness of where the camera should be placed in any particular scene. In the commentary, it’s mentioned that Patterson had no interest in moviemaking, but loved exploitation, and it’s very apparent that this was all thrown together because he had access to an actual execution chamber and chair … the grim reality of which highlights the ineptitude of the rest of the movie.

*

Joe D’Amato

Aristide Massaccesi was an incredibly prolific cinematographer who, under the pseudonym Joe D’Amato, was also an incredibly prolific exploitation director. He was much better in the former role than the latter, but even so some of the movies he directed have big cult followings. Perhaps most famous (notorious) is Anthropophagous (1980), a video nasty with a legendary climax. That moment is more disturbing in conception than execution, because it comes at the end of what is really a rather dull movie.

As in Narciso Ibanez Serrador’s Who Can Kill a Child? (1976), some tourists arrive on a small Mediterranean island and find it seemingly deserted. It’s not the kids who’ve killed the adults here though, but a madman cannibal. Everything about the movie is perfunctory, from the cliched character conflicts to the very unatmospheric stalk and kill sequences. The monster (co-writer George Eastman) isn’t given any personality – and not much backstory (something about being shipwrecked as a child and having to eat at least one of his parents) – so when one of the survivors cuts him open and he resorts to chewing on his own intestines, it’s gross but dramatically ineffective.

That was the moment which attracted a fan base, so it isn’t too surprising that D’Amato and Eastman started their follow-up, Absurd (1981), with an echo of it: somewhere in America at night, Eastman is being pursued by a grim-faced man (Edmund Purdom) and he gets hooked on the spikes at the top of a gate. He rings the doorbell of a suburban house and when the door opens, he stumbles in with his guts hanging out.

But it’s not the end of him; turns out he’s the result of a genetic experiment, which gives him superhuman healing powers … in effect, he’s immortal. He’s also a soulless killer who ends up stalking the family in the house as ineffectual local police and that grim-faced man try to track him down. That man is a priest who for some reason was involved in the experiment.

Written by Eastman (the acting alias of Luigi Montefiore), one of the great character actors of Italian exploitation (I first noticed him as Trentadue in Mario Bava’s Rabid Dogs [1974/1996]), Absurd may not be any better-crafted than Anthropophagous but there’s more going on and there’s a lot more screen time for Eastman, so overall it’s more entertaining. Although I’ve only seen a small fraction of D’Amato’s output, I’ll go out on a limb and say that his ode to romantic necrophilia, Beyond the Darkness (1979), is probably his best work.

Both films get decent if unspectacular transfers on Severin’s Blu-rays, plus a bunch of interview featurettes and an alternate Italian-language cut of Absurd, along with a soundtrack CD.

*

Roy Ward Baker and Amicus

Roy Ward Baker was a journeyman director who could make something out of whatever project came his way, could sometimes transcend the material, and on occasion got to do something to which he would completely commit himself, resulting in a classic. The two highest points of his long career were A Night to Remember (1958) and Quatermass and the Pit (1967), but there was a lot of good work in the 1950s and early ’60s (Don’t Bother to Knock [1952], Inferno [1953], Flame in the Streets, [1961]). He spent much of his last thirty years directing episodic television, but from the late ’60s through the mid-’70s he became something of a house director for Hammer (eight features) and then Amicus (four features), with mixed results. He didn’t seem entirely comfortable with Hammer’s increasing turn to gratuitous nudity in movies like The Vampire Lovers (1970), although his Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971) is one of the studio’s more interesting later releases.

Maybe Baker was a little more at home at Amicus, a slightly more conservative company than Hammer, at least when it came to sex. Three of his four features for producers Max J. Rosenberg and Milton Subotsky belong to the company’s very successful series of horror anthologies (the final one, The Monster Club [1981], tamely aimed at a much younger audience), while the more problematic fourth was Amicus’ most obvious attempt to imitate Hammer.

Baker’s first film for the company was the best of the anthologies. Asylum (1972) was written by Robert Bloch, who had been working for Amicus since The Psychopath in 1966, and was based on four of his own stories. It followed the well-established formula of a frame within which various characters get to relate their own terrible experiences (or sometimes learn of their own terrible future fates) – the original inspiration for the series was Subotsky’s admiration for Ealing’s Dead of Night (1945), still the quintessential horror anthology film. In this case a doctor arrives at an institution for the incurably insane and is set the task of discovering which of the inmates is the former head doctor.

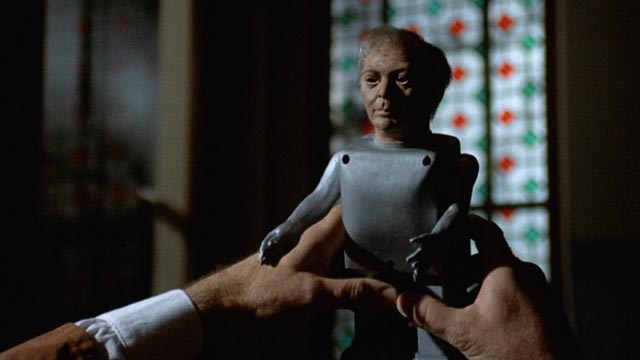

He listens to each story – a murdered wife’s dismembered body reanimates in order to get revenge on her faithless husband and his mistress; a woman’s murderous alter ego punishes those who torment her; a man commissions an impoverished tailor to make a special suit which will have the power to reanimate his dead son (previously adapted by Bloch for a 1961 episode of Thriller); and finally an inmate crafts dolls with the faces of his enemies, somehow instilling them with life to carry out his murderous plans. After hearing all their stories, the young doctor guesses wrong and ends up paying the price …

The cast is excellent – the format enabled the company to hire big names for just a day or two of work, giving a real boost to the films’ production values. Robert Powell is the new doctor, Patrick Magee is the acting director, and the stories are packed with notable actors: Barbara Parkins, Sylvia Syms, Richard Todd, Barry Morse, Peter Cushing, Charlotte Rampling, Britt Ekland, Herbert Lom, James Villiers, Megs Jenkins, Geoffrey Bayldon. Production values are good, pacing tight, the small budget only really apparent in some weak effects – the reanimated body parts wrapped in butcher paper are seen too clearly to be convincing, and little plastic walking robot toys are used for the murderous dolls because stop-motion would’ve been too expensive.

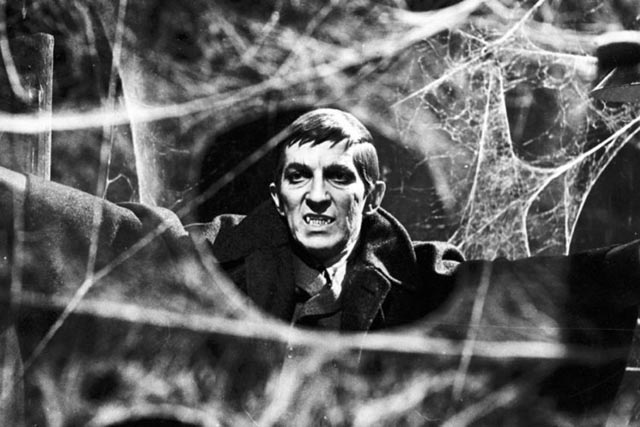

The following year, Baker made the company’s only attempt at Gothic horror, And Now the Screaming Starts (1973), adapted by Roger Marshall from a novel by David Case. It’s unusual for an Amicus film not just because of the period setting, but for the level of nastiness behind the haunting of a family estate by a spectre with torn out eyes and severed hand (the hand shows up frequently, stalking the halls). The young master of the estate brings his bride home, only for her to immediately start seeing and being threatened by the ghost. There’s a dark family secret known to everyone, but no one is willing to tell her, leaving her to start doubting her own sanity.

We eventually learn that, as a virgin bride, she is the target of a two-generation-old curse leveled against her husband’s grandfather by a tenant who was horrifically wronged. Granddad was a debauched monster who, for the amusement of his drunken friends, claimed the droit de seigneur on the wedding night of one of his tenants, raping the bride and cutting the man’s hand off with an axe when he unsurprisingly objects. The ghost of that woodsman is now haunting the estate and it becomes apparent that this spectre is the father of the child the current master’s new wife is carrying.

This is pretty dark and unpleasant stuff, rather strange in a movie whose audience is most likely to be kids. As a ghost story, it’s too crude to support the kind of subtle ambiguities which mark something like Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1961) or Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1961). It doesn’t help that Baker can’t muster much atmosphere, even though he once again has a fine cast – Stephanie Beacham as the bride, Ian Ogilvy (no stranger to grim horror just five years after Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General [1968]) as the husband, Peter Cushing and Patrick Magee as a pair of doctors, Geoffrey Whitehead as the woodsman, and Herbert Lom as the despicable grandfather.

And Now the Screaming Starts was a departure for Amicus, but it couldn’t be counted a success and they immediately went back to horrors set in the contemporary world. Baker returned to Hammer for The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974), then mostly worked on television series for the remainder of his career. His final collaboration with Subotsky wasn’t even produced under the Amicus banner, the company having essentially disappeared after three cheap and cheerful Edgar Rice Burroughs adaptations in the mid-’70s.

Both Asylum and And Now the Screaming Starts get decent treatment from Severin on Blu-ray, with solid if unexceptional transfers, director commentaries ported from previous DVD releases, and new and archival featurettes.

*

Master of Dark Shadows (David Gregory, 2019)

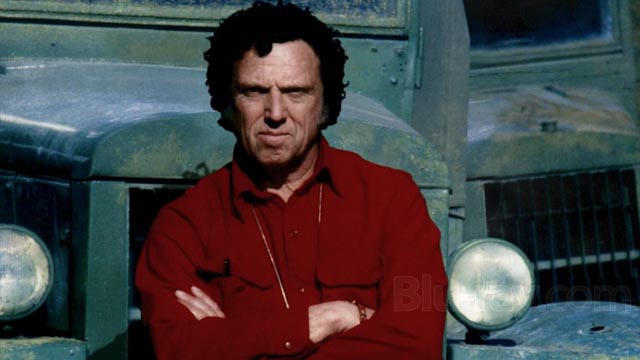

I was a bit disappointed by David Gregory’s new documentary, Master of Dark Shadows (2019), his first feature since Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau (2015). This has little to do with the film’s intrinsic qualities – it’s an efficient account of its subject – but is more about my own position as a viewer. The fact is I’ve never seen the near-legendary daytime horror soap Dark Shadows which ran from 1966 to ’71, though I’ve known about it for fifty-odd years, so I have no personal connection although I’m more or less aware of its pop culture importance, whereas my interest in Richard Stanley and personal appreciation of the film which finally emerged from the tortured production of the 1996 version of Island of Dr. Moreau gave me a vested interest in Gregory’s previous documentary.

But perhaps more importantly from a dramatic point of view, failure and catastrophe are simply more interesting than success. Producer-director Dan Curtis achieved much of what he set out to do, turning a fragment of a dream into a long-running TV show which was tolerantly supported by network executives as it grew and evolved, eventually becoming a genre touchstone which has sustained an enthusiastic community of fans for five decades since it went off the air.

Curtis himself continued to be an influential figure in television production as producer (The Night Stalker, 1972) and sometimes director (The Night Strangler, 1973; Dracula, 1974; Trilogy of Terror, 1975), achieving his career peak with two epic mini-series based on Herman Wouk’s sprawling World War Two novels The Winds of War (1983) and War and Remembrance (1988-89). In other words, Master of Dark Shadows is a story of success, well-told but without much in the way of dramatic conflict. It did, however, pique my interest in the soap in a way it had never been piqued before. The best part of the doc is its account of how the show gradually evolved over a period of years, with Curtis and his team of writers introducing more and more fantasy and horror elements, stretching the boundaries of what the form could contain … and paving the way, years ahead, for what now seem like familiar and inevitable long-form television fantasies by creators like Joss Whedon and J.J. Abrams.

The MPI Blu-ray includes a bunch of archival features promoting Dark Shadows during its run and recalling it at fan conventions over the years, but the most interesting extra is a 1954 episode of a CBS anthology series called The Web. Written by DS’s chief writer Art Wallace, The House provided a kind of template for the initial stretch of Dark Shadows before the ghosts and vampires arrived on the scene.

*

Viy (Konstantin Ershov & Georgiy Kropachyov, 1967)

Russian fantasy and horror movies from the Soviet period often had the flavour of folk tales, none more so than Viy (1967), directed by Konstantin Ershov and Georgiy Kropachyov, with design and effects by Aleksandr Ptushko. Based on a story by Nikolai Gogol first published in 1835, the film depicts the fatal encounter of a young seminarian with a witch and a whole host of demons. Heading home for the summer, Khoma (Leonid Kuravlyov) and his friends seek shelter for the night at a remote farm. As he settles down to sleep in the barn, Khoma is enchanted by an old crone who harnesses him and flies on his back across the country. When they land, he beats her savagely with a stick and she transforms into a beautiful girl.

Khoma hurries back to the seminary, only to discover that he has been summoned by a Cossack landowner to come and read prayers over his dying daughter. Arriving at the farm, he learns that the girl has just died – and realizes that she’s the witch he had beaten (Natalya Varley). Her father insists that Khoma must read prayers over her for three nights, locked with her body in a chapel. Reluctant and fearful, he draws a protective chalk circle around himself and calls on God as she rises and tries to attack him. These attacks escalate each night, ending only when the cock crows at dawn.

On the third night, the witch unleashes a horde of demons and goblins, finally calling on Viy, something like a goblin lord summoned from deep in the Earth. Seemingly abandoned by God, his paltry protections failing, Khoma dies in terror just as the cock crows. Whether this is due to his own moral failings – he’s a weak-willed boozer devoid of any genuine faith – is unclear, but certainly God seems deaf to his pleas.

The film’s imagery is rich and colourful, with Severin’s new Blu-ray a big improvement over RusCiCo’s 2000 DVD edition. The mix of real landscapes and studio exteriors emphasize the fairytale ambience of the story, while Ptushko’s practical and optical effects for the witch’s attacks, escalating in ferocity until the third night’s phantasmagoric assault with hordes of demons pouring out if the chapel walls, are spectacular visual magic.

In addition to the gorgeous transfer, the disk includes a typically eccentric discussion by Richard Stanley of the original story and the adaptation, plus an even longer but rather rambling and unfocused piece about Russian fantasy and science fiction film by John Leman Riley.

Comments

I really enjoyed those old anthology horror movies when I originally saw them back in the 1970s, including Asylum, Vault of Horror, Tales from the Crypt, Tales That Witness Madness and others. I remember typing out the stories after seeing the movies so that I would remember them. Every one of them had at least one memorable story that I can recall to this day.

Funny, back in the day, before home video, I’d do that too … try to write down the plot of a movie I’d just seen so I’d be able to remember it. Now that I have everything on disk, I barely remember anything! Have a really annoying habit of vividly recalling an individual scene without being able to remember what movie it’s from!