Recent miscellaneous viewing, part three

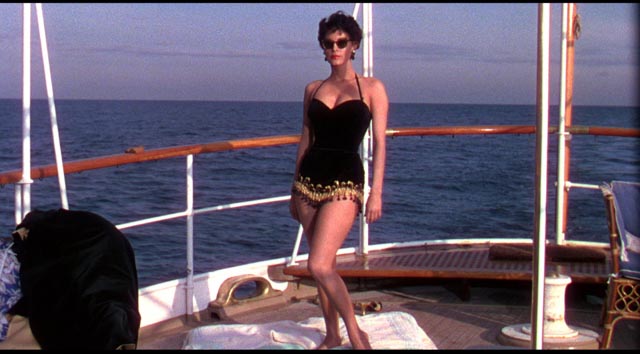

in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s The Barefoot Contessa (1954)

The Barefoot Contessa (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1954)

Although I like the work of Joseph L. Mankiewicz, steeped as it is in verbal wit and filled with great performances by great actors, I somehow had never seen The Barefoot Contessa (1954) until I recently watched it on Twilight Time’s Blu-ray. The witty dialogue is there, and the great performances, all captured in rich Technicolor imagery courtesy of Jack Cardiff … but I found myself frequently wondering what exactly it was about. Framed by a sour view of the movie business, it stretches the limitations of what was allowed by the Production Code in unexpected ways and ends on a depressingly downer note. But what is Mankiewicz trying to say in this first feature produced by his own independent company, Figaro?

Structurally, it has echoes of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950), which had been an international hit a couple of years earlier. Beginning with the funeral of the title character, Maria Vargas (Ava Gardner), we are shown the last two years of her life in flashbacks narrated by several of the men at the rainy graveside. First, and most prominently. there’s Harry Dawes (Humphrey Bogart), a writer-director whose career is on the downslope. Harry has hooked up with the grimly egotistical multi-millionaire Kirk Edwards (Warren Stevens, supposedly based on Howard Hughes), who is determined to discover “a new face”, dragging Harry and PR man Oscar Muldoon (Edmond O’Brien) to Spain hoping to sign a famous dancer to an exclusive contract.

The dancer, Maria Vargas, is repelled by both Edwards and Muldoon, but Harry wins her over, becoming her mentor and protector … but, going against the melodramatic grain, not her lover. He’s happily involved with his script girl Jerry (Elizabeth Sellars) and maintains a fatherly distance from Maria even as he makes her an international star in three features bankrolled by Edwards.

Through Harry, we learn about Maria’s hard childhood, her fantasies about escaping the dirt and poverty, while simultaneously being energized by her roots – the title refers to her dislike of shoes and preference to walk barefoot on the earth. What is surprising, given the time it was made, is Maria’s openly displayed sexuality. When Harry first meets her, she’s making out with one of the musicians in her dressing room, a man who tags along as she begins her rise in the movie business. But while she maintains that relationship, she physically rejects the ultra-rich Edwards and later the even richer South American oligarch Alberto Bravano (Michael Powell favourite Marius Goring).

Maria finally finds true love and quits the business in order to marry Count Vincenzo Torlato-Favrini (Rossano Brazzi), but there are hints of a cloud over the Count which we get from some cryptic conversations between him and his sister Eleanora (Valentina Cortese), during which they talk about themselves being the end of the family line and whether it’s fair to Maria to bring her into the family.

Maria only learns his secret on their wedding night, when he reveals that wounds he suffered during the War have left him impotent – there can be no heir to carry the family on beyond this generation. Although they love each other, this naturally causes stress. Maria takes a lover … but apart from fulfilling her own needs, as she explains to Harry during their last meeting, she uses the affair to present the Count with the gift of a child.

She never gets to tell her husband this, though; she dies in an act of violence and Harry sees no point in reporting what he knows. And so we end up back at the funeral as the rain lets up and the sun comes out. What we have learned about the dead woman, now almost a mythic character, all comes from the men who observed her during those last two years, a mediated romantic ideal, both desirable and intimidating because she insisted on maintaining control of her own sexuality.

But what does the narrative trajectory mean? Harry feels guilt because he was the one who persuaded her to embark on a course which led to her destruction, but the implication is that Maria’s own fierce independence made that destruction virtually inevitable; her refusal to submit to any man’s definition of her role in her own life, her insistence on clinging to her own romantic fantasies, could have no other end than that of victim, destroyed by male insecurity.

In the end, The Barefoot Contessa is a rather depressing movie. Despite pushing against the Code – unmarried sex, impotence, pregnancy from an affair, and female sexual pleasure for its own sake – it asserts that Maria’s harsh punishment is inevitable, dressing her fate up in the guise of tragedy to conceal an underlying misogyny.

Not surprisingly, the image on the disk is rich and colourful, but there are quite a few moments displaying misalignment of the three Technicolor colour separation negatives, resulting in a soft, slightly blurred picture. The main extra is a commentary by Twilight Time’s Julie Kirgo with David Del Valle.

*

Lucio Fulci

in Lucio Fulci’s One on Top of the Other (aka Perversion Story, 1969)

One on Top of the Other (aka Perversion Story, 1969)

One on Top of the Other (aka Perversion Story, 1969), Lucio Fulci’s first giallo, takes a big risk by calling up memories of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), not just in its story of a man obsessed with the doppelganger of a dead woman, but in its use of San Francisco as the main setting. Successful doctor George Dumurrier (Jean Sorel) is trapped in a loveless marriage to Susan (Marissa Mell), a semi-invalid suffering from severe asthma. He’s also having an affair with Jane Bleeker (Elsa Martinelli). When Susan dies suddenly from an asthma attack, it appears that he’s free. But life quickly gets complicated.

He’s led to a strip club where the star attraction, Monica Weston (Mell in a dual role), bears a striking resemblance to his dead wife – except for different hair and eye colour. Monica is strong, sexually active, and rather cruel to her lovers (particularly the pathetic Benjamin Wormser [Riccardo Cucciolla]). Dumurrier becomes obsessed with Monica as he also falls under police suspicion for the sudden death of Susan – the fact of his affair and a rather large insurance payout on a policy only recently purchased seem to point to murder; he denies knowing about the insurance despite his signature being on the papers.

The story unfolds less coherently than Vertigo, leading to what is almost a powerfully suspenseful climax with Dumurrier strapped into the gas chamber at San Quentin (the real thing, not a set, which makes it extra creepy) … but the final twist is fumbled. Fulci had a better grasp on his material when he made his next two gialli – A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (1971) and his masterpiece Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972).

The image on Mondo Macabro’s Blu-ray is excellent and there are some substantial extras: interviews with stars Sorel and Martinelli and a lengthy discussion by Fulci expert Stephen Thrower, totaling almost an hour-and-a-half.

*

The New York Ripper (1982)

Fulci ended his strong streak of horror movies from the late 1970s and early ’80s with what remains his most controversial film. Although known for his misanthropy and graphic violence, he seemed to go too far with The New York Ripper (1982), a movie which leaves the viewer with a decidedly grubby feeling. The lingering attention to a series of brutal murders in the title city aroused condemnation of Fulci’s apparent misogyny and it’s very difficult to excuse the brutality inflicted on a number of women, even if it is valid to point out the director’s contempt for the male characters. But it’s also true that the film doesn’t put its audience in the position of the unknown killer’s twisted point of view – avoiding the kind of uncomfortable identification with a monster like Henry in John McNaughton’s Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986).

Beyond the nastiness of The New York Ripper, it is actually one of Fulci’s best-directed movies, not to mention one of his most tightly structured gialli (co-written by frequent Fulci collaborator Dardano Sacchetti). It’s a straightforward mystery/thriller which goes for a gritty, realistic tone with none of the surreal excesses of his early gialli, closer instead to the socially observant Don’t Torture a Duckling. To this end, Fulci and cinematographer Luigi Kuveiller (who had previously shot such genre landmarks as Paul Morrissey’s Flesh for Frankenstein [1973] and Blood for Dracula [1974] and Dario Argento’s Deep Red [1975], as well as Fulci’s own A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, not to mention Elio Petri’s Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion [1970] and Property is No Longer Theft [1973]) make excellent use of the New York City locations, adding to the movie’s grungy authenticity.

Blue Underground have lavished an embarrassing amount of attention on this problematic movie, with a spectacular 4K restoration from the original negative, a commentary from Troy Howarth, and a second Blu-ray disk packed with interviews with cast members, co-writer Sacchetti, and Stephen Thrower. To top it off, there’s also a CD of Francesco De Masi’s soundtrack.

*

Skinner (Ivan Nagy, 1993)

Speaking of problematic, transgressive horror, what to say about Ivan Nagy’s Skinner (1993), a mix of psycho horror, slasher and giallo with its own distinctive tone and atmosphere? I found echoes here of such diverse movies as Richard Fleischer’s 10 Rillington Place (1971), Noel Black’s Pretty Poison (1968) and Gerald Kargl’s Angst (1983). A quiet, mild-mannered man named Dennis Skinner (Ted Raimi) rents a room from unhappy small town housewife Kerry Tate (Ricki Lake), whose fairly obnoxious husband Geoff (David Warshofsky) is away most of the time driving his long-haul truck. A tentative bond forms between Kerry and Dennis, but he’s not at all what he seems on the surface. There’s a disturbing secondary meaning to the title.

Working as a watchman at a run-down factory, Dennis spends his spare time killing prostitutes and, in emulation of Ed Gein, taking their skin to wear as he dances around the empty plant. The only explanation for this bizarre behaviour is a flashback which reveals that as a child he was forced to sit and watch his father perform an autopsy on his mother.

Despite Dennis’ disturbing pastime, there’s an odd sweetness, even innocence, about him which makes his relationship with Kerry quite poignant if ultimately impossible. Things begin to unravel with the appearance of a mysterious woman named Heidi (Traci Lords), who has come looking for revenge. With long hair hanging down over her face, a large droopy hat and a big overcoat, Heidi is concealing her own terrible secret: one of the few victims to have survived an encounter with Dennis, she is hideously scarred.

With an interesting script by Paul Hart-Wilden, a strong cast – the three leads give nuanced performances – and excellent photography by Greg Littlewood, Skinner is a much better film than you’d expect, coming very late in the slasher wave which was pretty much exhausted by 1993. While there are outrageously disturbing moments (one in particular disowned by writer Hart-Wilden, who says it was definitely not in his script), Nagy’s direction is quite artful, taking its time so that the characters are given space to grow, with images which are almost poetic in their visual abstraction – frequently involving water, which evokes something primal yet not fully defined.

The image on Severin’s Blu-ray is excellent. Extras include an interesting archival interview with Nagy, who had a, shall we say, colourful history … escaping Hungary in the ’50s, getting into the film business, directing a lot of television and eventually porn, he was caught up in the Heidi Fleiss prostitution scandal around the time of Skinner’s production. There are also interviews with writer Hart-Wilden and star Raimi.

*

Shopper’s Drug Mart

As I’ve mentioned here before, I’m a sucker for a bargain … even when it’s something I don’t need and, to be honest, don’t really want. Hence a number of recent acquisitions thanks to a discount movie rack at my local drugstore. I stop in for a lottery ticket, a paper, maybe a bar of chocolate and always take a look at the spinner near the checkout, as often as not grabbing something because it looks like “value for money”.

Which explains why I’ve recently binged, on Blu-ray, the Mummy trilogy (I still like the first as an entertaining comedy-horror-adventure, though the two sequels are increasingly awful), the Expendables trilogy (dumb action which rests on nostalgic affection for a bunch of aging stars who saw their best days in the ’80s) and an oddly random collection of videogame-based animation and live action in Halo: The Complete Video Collection.

Not sure what to make of the latter, having never played Halo and not having any previous knowledge of the game’s world. The set consists of Halo Legends (2010), a collection of animated shorts set in the Halo universe; Halo, the Fall of Reach (2015), a short animated feature (just over an hour); plus two live-action features, Halo: Forward Into Dawn (2012) and Halo Nightfall (2014). All of them present small, fragmentary pieces which refer to an obviously much larger meta-narrative, and individually they offer mildly entertaining generic B-movie pleasures. I assume this would all mean more to dedicated gamers. There are two bonus disks packed with featurettes about the game and commentaries on the four movies (why the commentaries aren’t included on the main disks is a puzzle).

Finally, I picked up Zack Snyder’s 300: The Ultimate Experience, the Blu-ray of his absurd but entertaining homo-erotic epic about well-oiled Spartans facing off against a vast Persian army, which comes inside a book with heavily illustrated production notes and, on the disk, a load of special features which I think are all carried over from the special edition DVD.

I wouldn’t have bought any of these except for their easy availability on the drugstore rack, priced between six and ten bucks apiece … but kind of enjoyed wasting my time on them anyway.

Comments