Speed reviewing, Nov. 2019 – part three

Mindwarp/Brainscan

(Steve Barnett/John Flynn, 1992/1994)

This Mill Creek Blu-ray double-feature made for a diverting evening. There’s virtual reality, computer gaming, a post-apocalyptic wasteland populated by mutant cannibals, murders, voyeurism, threatened incest, and (relatively) happy endings. Oh, yeah, and Bruce Campbell and Angus Scrimm. The cheaper, scrappier Mindwarp (1992) is the more entertaining of the two, with Judy (Marta Martin) rebelling against the sterile society which lives underground after the final war. Everyone spends pretty much all their time hooked into a central VR system, dreaming their lives away and she’s had enough. For her defiance she’s ejected to the radioactive surface, attacked by those cannibal mutants, and rescued by scavenger Stover (Campbell, in a pretty straight role). Before you can say Mad Max and A Boy and His Dog, they’re captured by the mutants and taken into another underground world, this one filthy and violent, where the pathetic denizens slave away for the Seer (Scrimm), salvaging the remnants of pre-war technology. Turns out he’s Judy’s long-lost Dad and he plans to repopulate the world by making babies with her. The final twist, given the initial VR set-up, isn’t a surprise, but Barnett keeps things lively and the obviously tiny budget (financed by Fangoria) is stretched to the limit with some nicely detailed and cluttered production design. Plus there’s Bruce Campbell and Angus Scrimm.

The bigger-budgeted Brainscan (1994) suffers from the same curse as other movies from around that time (like Irwin Winkler’s The Net [1995]) whose depiction of computer technology now looks embarrassingly quaint. Edward Furlong (three years out from Terminator 2) is a suburban kid who’s rigged his room with the latest equipment, including a talking, apparently AI-driven video-phone. He orders what’s advertised as the ultimate videogame – it comes on interactive CD-ROM! – one which gives you an awesome VR experience. Turns out it puts the user into an increasingly dangerous situation as the game thrills (involving the excitement of actually killing people) are played out in the real world. With the cops closing in, the game traps the kid ever deeper in a web of violent crimes. It also turns out that the game is controlled by a demon who shows the kid the real dangers of giving yourself over to virtual experiences instead of engaging with the real world … yep, there’s a moral writ very large, and given a second chance, the kid trashes his tech and goes out to party with his friends.

Director John Flynn never managed to fulfill the promise of his debut feature, The Sergeant (1968), although he did have some occasional commercial success – the Paul Schrader-scripted Rolling Thunder (1977), the Stallone-starring Lock Up (1989). Brainscan is as generic as it gets, a movie made by people who want to seem hip and up-to-date, but which was already dated by the time it was released.

*

Galaxy of Terror (Bruce D. Clark, 1981)

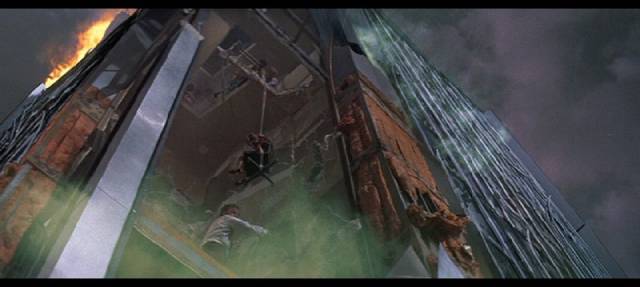

Bruce D. Clark’s Galaxy of Terror (1981) was one of a string of low-budget space epics produced by Roger Corman in the wake of the success of Star Wars and Alien. Like most of them, it’s kind of dumb, but entertaining. A crew are sent to a strange planet to find out what happened to a previous expedition – no surprise, the earlier crew all died. As they explore, they find a giant pyramid and inside each in turn is confronted by his or her worst fear. There’s a lot of running around on decent if limited sets, some amusing overacting (it’s always fun to see Sid Haig give it his best shot), and a final twist which, by coincidence, is very much like the conclusion of Mindwarp. Shout! Factory has upgraded their release with a new 4K scan, which reveals more detail than their previous Blu-ray; otherwise the contents of the disk are identical – same commentary, same making-of featurettes – except for the absence of the script PDF.

*

They Live (John Carpenter, 1988)

Over the years, I’ve gradually warmed to John Carpenter’s They Live (1988). Back when I saw it in its original theatrical run, it seemed to suffer from Carpenter’s chronic problem of creating an interesting set-up and then not really following through on the narrative possibilities. It also had that mid-point which seemed to be mocking the audience – with Roddy Piper and Keith David duking it out interminably over a pair of sunglasses in a back alley. In memory, that seemed to go on forever, but on this viewing I timed it and it’s only about 5.5 minutes. I guess when you hire a professional wrestler as your star you want to exploit the talents he’s best known for. But actually Piper gives a decent performance as a working guy down on his luck who gradually realizes that it’s not just a matter of luck, that in fact the whole society he lives in is stacked against him and his kind, in favour of the obnoxiously privileged.

A sci-fi story satirizing Reagan’s America, They Live actually seems more relevant now than it did back then – economic inequality has escalated steadily and the elites control the media and feed the oppressed population an endless supply of propaganda about how it’s imperative that the rich be allowed to accumulate ever more wealth. The rich have become so distanced from the rest of society that it seems quite appropriate to depict them as rapacious aliens stripping the planet of everything of value.

The Shout! Factory Blu-ray is a definite upgrade from my old DVD copy, with a detailed and colourful image, plus a collection of production featurettes and interviews, and a commentary from Carpenter and Piper.

*

Earthquake (Mark Robson, 1974)

Having re-watched Mark Robson’s Earthquake (1974) not long ago, I thought I’d give the extended television cut on Shout! Factory’s Shout Select Blu-ray a shot. Split into two ninety-minute parts, it required some padding and it’s amusing to see just how obvious that material is. It wasn’t a matter of slipping in a bunch of deleted/extended scenes from Robson’s shoot – as far as I could tell, there was only one of those – rather, someone else came along and shot an entirely new subplot which has absolutely no connection with the rest of the movie and then stretched that material to unbearable lengths. It doesn’t help that everything else is panned-and-scanned, diminishing the large scale destruction which is the movie’s main attraction.

The one new sequence involving characters already in the movie has Marjoe Gortner’s obnoxious homophobic neighbours looting a pawnshop and confronting the gun-wielding widow of the dead owner who’s lying behind the counter. This explains the suitcase of jewellery they’re carrying later just before Gortner kills them. The new, extraneous subplot is set entirely on board an airliner heading for Los Angeles. On board is a young engineer going west to take up a position in Charlton Heston’s company. He’s accompanied by his pregnant young wife, who looks out the window at the Grand Canyon while he uses a marker to highlight complimentary information about Heston in a magazine so he can suck up to the new boss. The plane reaches L.A. just as the quake hits and almost crashes as the runway starts to break up; it manages to get off the ground again and, for some reason, heads for Hawaii. The engineer decides he’ll immediately go back to L.A. and help rebuild the city; his wife promises she’ll be right there at his side.

The new 2K scan looks good, the many matte and miniature shots slightly improved over the old Blu-ray. There are featurettes on John Williams’ score, Albert Whitlock’s matte paintings, and the new technology of Sensurround, which amped up the effect of movie theatre audio just before Dolby Stereo changed everything.

*

The Haunting of Hill House (Mike Flanagan, 2019)

I was ambivalent about watching Mike Flanagan’s “reimagining” of Shirley Jackson’s classic haunted house novel, which had previously been adapted in 1963 by Robert Wise (a classic in itself) and again in 1999 by Jan De Bont (an abomination). I’d heard about the radical changes Flanagan had made – the disparate group of psychic researchers in the original had been transformed into a family, five kids who had spent part of their childhood being traumatized by the house and now are being drawn back by forces which aren’t done with them yet. As is often the case with this kind of tinkering, I wonder why the filmmakers didn’t simply come up with their own story – but of course it’s all about brand recognition.

But a friend had recommended the series highly, so when it turned up on disk (a surprise given Netflix’s usual reluctance to make any of their productions available anywhere except on their streaming service) I decided to give it a shot. I ended up binging it in two days and for the most part I was totally engaged. The direct references to Jackson were occasionally irritating – the opening narration, occasional lines of dialogue – seeming to be shoehorned in to justify the use of the title. But Flanagan (who wrote many episodes and directed them all) had put together an intricate narrative which switches between present and past, and within those two periods also keeps looping back on itself to follow different characters whose trajectories repeatedly diverge and reconnect.

The cast for the most part is very good, particularly the kids who witness the horror of their mother going mad and realize before their parents do that there’s something very wrong with the huge old house in which they have to spend the summer while it’s being renovated for flipping. Flanagan has shown in the past that he’s a skilful creator of unsettling atmosphere which he punctuates with effective jump scares, and that ability is on full display here. The house possesses a malevolent power which shapes (and largely ruins) the kids’ subsequent lives as they grow apart with their various self-destructive coping mechanisms. Now they have to overcome their differences and confront their past together (which sounds more like Stephen King than Shirley Jackson).

All of this works well, with the house gradually revealed to them (and the audience) as a living entity which eats the minds and lives of those who reside in it. It’s an evil place (its echoes of the Overlook Hotel are a reminder of how much Stephen King owed to Jackson) populated by horrors which were once its human inhabitants. All of this is so effective that it’s doubly disappointing – infuriating – that Flanagan blows it all in the final episode, in which deep horror gives way to maudlin New Age uplift, with the house suddenly a haven providing solace to those who have lost their loved ones by reuniting them as happy ghosts who get to spend eternity together. I mean, WTF? Why did all those spirits evoke such horror and drive Mom insane if it’s all supposed to be warm and fuzzy? That final episode pretty much negates everything we’ve seen in the previous nine and retrospectively trivializes all the horror and emotional pain.

*

The Killing of America (Sheldon Renan, 1981)

The Mondo genre has always been pretty disreputable, though the original movies by Franco Prosperi and Gualtiero Jacopetti, for all their sensationalism, did possess a degree of journalistic and philosophical integrity (the appalling Africa Addio [1966] and Addio zio Tom [1971] were among the first movies to address head on, respectively, post-colonial chaos in Africa and the history and lasting impact of the slave trade). Most of the imitators of that Italian duo merely strung together a bunch of random bits and pieces intended to amuse or gross-out undemanding audiences, eventually descending to the level of the Faces of Death series, which were little more than snuff films disguised as documentaries.

What separates Sheldon Renan’s The Killing of America (1981) from that stuff is a discernible political point of view – courtesy of writer Leonard Schrader (brother of Paul) and his wife Chieko. Renan was a skilled archival specialist and together with editor Lee Percy he accumulated a dense mass of material which illuminated how America’s mythology of rugged individualism and distrust of the political organization of a shared community has resulted in what amounts to an addiction to violence. The results are pretty gruelling and at times hard to sit through as the filmmakers catalogue assassinations, state-sanctioned violence and the heinous acts of individuals who express themselves through the mutilation and murder of their fellow citizens. Much of the film deals with the chaos of the ’60s, and it ends with the murder of John Lennon (which occurred as editing was nearing completion), but rather depressingly it seems even more pertinent now in the age of Trump, with a President increasingly spurring his followers to commit acts of slaughter, and white supremacy aggressively reasserting itself.

Severin’s Blu-ray offers two different cuts – the filmmakers’ preferred 95-minute edit and the longer (115-minute) Japanese version, which includes a section on “positive” American traits in order to take some of the sting out of the criticism (though a lot of those positives reflect an attraction to thrills and physical extremes which actually feeds into the addiction to violence which is the film’s subject). There’s a commentary from Renan, plus interviews with Renan and Percy, and a featurette with Nick Pinkerton about the Mondo genre.

Comments

The ending of Haunting of Hill House bothered me, but I’m able to ignore it… I really liked the previous episodes. In fact, I barely remember the last episode, other than the last ridiculous misquote from the book. The ending of Lost was far more of a disaster because the entire series had been built around revealing the true nature of the island. I can still watch Lost and enjoy it… but I have to stop before the end.

I have to agree about Lost – one of the most miserably ill-conceived endings ever. At least Hill House was over in 10 episodes, so there wasn’t as much invested … after 6 seasons, the Lost fiasco was a huge betrayal of the audience.