Michael Radford’s adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984 (1984)

It might have seemed like a no-brainer – make a new film based on George Orwell’s dystopian masterpiece Nineteen-Eighty-Four in 1984 – but it fell to a young writer-director with only one previous feature, funded by music company Virgin, to bring it off. Starting late in 1983, Radford knocked out a script in three weeks and production began immediately. There had been a number of previous adaptations, most notably Rudolph Cartier and Nigel Kneale’s 1954 BBC dramatization, which benefited from being made just a few years after publication, with some location shooting in areas still ruined by the war.

Given the passage of time, with obvious differences between Orwell’s imaginative projection and the actual world of 1984, Radford had to make important creative decisions about how to approach his adaptation. Orwell was writing in the hot shadow of the war, as the world was still picking itself up from the horrors of Fascist totalitarianism – and while the Soviet bloc was entrenching itself more deeply in Communist totalitarianism. His book was a warning to the West – to England – about the danger of sliding down that slope. (The subject of the book is specifically totalitarianism; it could be either Fascist or Communist, left or right … Orwell doesn’t specify, because the mechanisms are so similar for both.) Democracy was a fragile thing, vulnerable to the same temptations which had led Germany and Russia along their parallel dangerous paths. By 1984, the Cold War had exhausted East and West; democracy was succumbing not to political totalitarianism, but rather to Capitalist corporate control. As powerful as Orwell’s vision was, and as astute as his dissection of that oppressive system was, it no longer provided an entirely accurate critique of the current situation.

And so, rather than trying to rework Nineteen-Eighty-Four to fit this changed world, Radford chose to make the film as if from the perspective of the year Orwell wrote it. While taking full advantage of the cinematic possibilities of the real 1984, he set the film in the future Orwell posited from 1948. This gives it an odd, distinctive tone which seems both faithful to the literary source and strangely distant. The result is a film which one can admire for its many accomplishments, while nonetheless being held at a chilly distance from the world it depicts and the characters who inhabit it. It’s like an artifact from a different timeline.

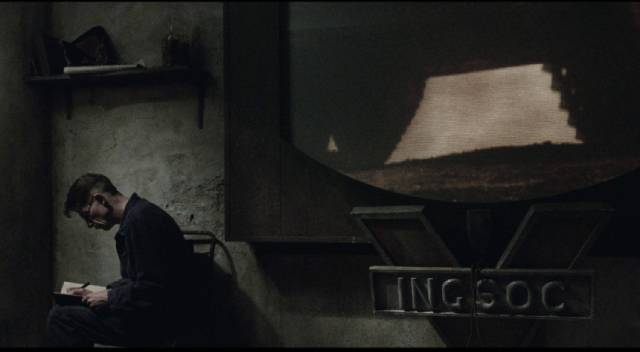

With what were fairly limited resources, Radford shot much of the film in the same abandoned part of London’s Docklands which Stanley Kubrick a couple of years later would transform into Hue during the Tet Offensive for Full Metal Jacket (1986). These industrial ruins, with collapsing buildings and streets piled with rubble, provide a convincing vision of a world crushed by perpetual war. Through this landscape wander equally crushed and colourless people, principal among them Winston Smith (John Hurt), a lowly worker in the Ministry of Information who spends his days rewriting history to erase inconvenient facts from the official record.

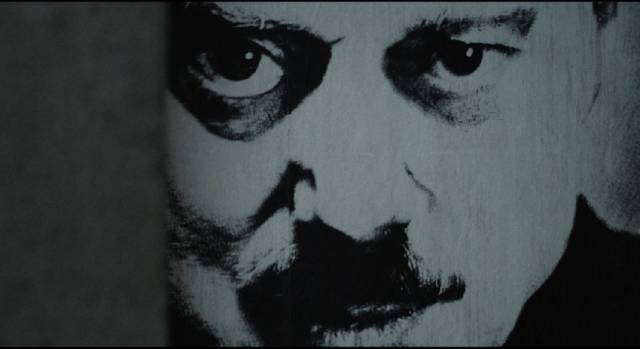

Smith’s chief sin is that he can’t quite stop himself from thinking about life in this world. Having found an empty journal in a junk shop in the prole area, he stashes it in a hole in the wall of his barren room and, hiding from the omnipresent surveillance screen, he keeps a diary of his life in which he questions the validity of the Party and the system it props up. As in Orwell’s novel, the subject is the methods the Party uses to control the thoughts and behaviour of its members – the proles don’t need much controlling; kept in their place by a steady diet of relentless propaganda about the necessity to sacrifice for the perpetual war effort, they have neither the time, the energy nor the will to question their lot. It’s those inside the Party who pose a threat to its domination, because they are the ones who are at risk of questioning – as Smith does – the legitimacy of its methods.

Smith’s small, private rebellion is complicated by his meeting Julia (Suzanna Hamilton). He’s initially suspicious that she’s out to trap him by getting him to expose his thought crimes, but it gradually becomes clear that her interest is sexual – and eventually emotional. Together they commit the crime of becoming attached to one another rather than solely to the Party. They find a private place in the prole area for their meetings, establishing a shadow domestic life, which is inevitably shattered when they are arrested – nothing can be hidden from the Party.

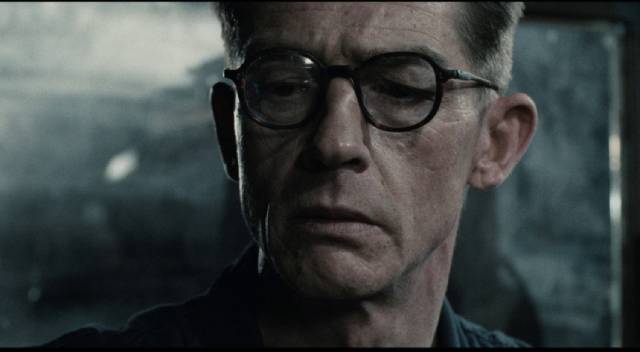

In the final act of the film, Smith is subjected to interrogation and torture by the insidiously quiet and friendly Party official O’Brien (Richard Burton in his final performance). This has nothing to do with establishing guilt – by definition Smith is guilty; he must be, because he’s been arrested – nor is it designed to elicit a confession. Or rather, not a confession of his actual transgressions – what he eventually admits to in a public broadcast is a bunch of crimes he hasn’t actually committed. That phoniness is a crucial part of the process, because the purpose of everything he’s subjected to is to get him to betray himself. He must reject his own identity and submit himself willingly to the Party, to allow them to define who he is … and the ultimate expression of this is his acceptance of the beneficence of Big Brother. He has betrayed himself and Julia, he has betrayed his own thoughts and emotions, and all he has left is his love of the forces which have stripped him of all humanity.

Radford’s adaptation retains much of the power of Orwell’s novel, if not Orwell’s black humour. Thanks to the bleak production design of Allan Cameron and the gritty, desaturated photography of Roger Deakins (it was just his third feature, and benefited from his experience in documentary), 1984 is a convincing dystopian vision which, while it diverges from the actual future, nonetheless chillingly illuminates the ways in which political power shapes the way we experience our own world … in fact, it is perhaps even more relevant today, with the rising tide of “alternate facts” and fake news, than it was in the middle of the reign of Thatcher and Reagan.

The 4K restoration used for Criterion’s Blu-ray release looks terrific, rendering this grim, colourless world with gritty detail. There are two soundtrack options – the original score by Dominick Downey and the one by the Eurythmics forced on Radford by David Geffen for marketing purposes. Radford now says that he likes both. Both are quite minimalist, used sparingly, providing atmosphere rather than dramatic emphasis.

The disk includes interviews with Radford and Deakins (who talks about his own work being technically flawed, though he’s proud of the film as a whole), and with Orwell authority David Ryan, who discusses the adaptation in relation to the source novel. There’s also some behind-the-scenes material and a text essay by A.L. Kennedy.

Comments

I prefer Brave New World.

Too bad no one has ever made a decent movie of that.