More Arrow …

Time Bandits (Terry Gilliam, 1981)

It’s been years since I last watched Time Bandits (1981), Terry Gilliam’s second feature after leaving Monty Python to go solo. I always preferred Jabberwocky (1977) because the episodic nature of Time Bandits seemed like a step backward, a bit of a return to Python’s sketch comedy. But watching it again in Arrow’s 2K restoration, it seemed quite a bit darker than I remembered – there’s a lot of death for what on the surface looks like a kids’ fantasy. While individual sequences vary in quality and effectiveness, the overriding narrative of Kevin (Craig Warnock)’s relationship with the Bandits provides a strong core, exploring the conflict between a child’s openness and curiosity and an adult world crushed and constrained by commercial materialism. The large cast is also terrific. The disk is packed with featurettes about the production, but doesn’t include a commentary – not even the one Gilliam recorded for the old Criterion DVD.

*

Miracle Mile (Steve De Jarnatt, 1989)

Steve De Jarnatt’s Miracle Mile (1989) has always had a good reputation, but I somehow never got around to seeing it before, despite the appeal of what I had heard about its story. I really wanted to like it – and appreciate its mix of genres – but I found it increasingly irritating and pretty much had to force myself to watch to the end. It begins as a romantic comedy, with visiting trombonist Harry (Anthony Edwards) falling for Julie (Mare Winningham) when he sees her at the Le Brea museum in Los Angeles. They talk; he agrees to pick her up that night at the end of her shift at a diner; but he oversleeps at his hotel and when he finally gets to the diner at 4:00AM she’s long gone. He tries to call her, and ends up answering the payphone outside, hearing a panicked man say that a nuclear exchange has begun with the Russians and there’s only an hour before the missiles will arrive.

After convincing the late night denizens of the diner to get out of the city, Harry sets off to find Julie and get her to a helicopter which will hopefully fly them to safety in time. Word of the war spreads and the city gradually sinks into chaos and violence. Which is all fine … but Harry seems to become a bigger and bigger fool as the hour passes, making increasingly dumb decisions which (for me at least) lose him any sympathy, while Julie remains something of a cipher to the end. And a grim end it is, negating the original romantic comedy tone with what’s intended to be a tragically romantic climax, the stupidity of war obliterating the value of ordinary life. Maybe it would have worked for me if only Anthony Edwards wasn’t so annoying.

The image is fine, there are two commentaries, and interviews with director and stars, plus a featurette on Tangerine Dream’s score.

*

Deadbeat at Dawn (Jim Van Bebber, 1988)

I first heard about Jim Van Bebber in 1999 when I picked up a copy of Charlie’s Family, the book about his ten-years-in-the-making movie about the Manson Family and their crimes. It was years later before I got to see the film, and several years more before I saw his first feature, Deadbeat at Dawn (1988). Maybe it was because I was so impressed by The Manson Family (1997) that I was disappointed with Deadbeat. But watching it again, I really liked its scrappy, punk energy. It was the first feature ever made in Dayton, Ohio, and Van Bebber had dropped out of film school to make it. He wrote, directed, starred, edited, did the gory make-up effects and all the stunts. Some of the latter were actually pretty dangerous and Van Bebber did get injured. That kind of commitment gives the movie a manic energy which makes budgetary limitations irrelevant.

Van Bebber plays gang leader Goose, who decides to give up the life for the sake of his girlfriend. But a rival gang, looking to kill him, ends up beating her to death instead. Goose gets pulled back in to take part in an armoured car robbery, but intends to get revenge. There are betrayals, murders and by the end more deaths than in the final act of Hamlet. It’s like a much bleaker, do-it-yourself Warriors kept afloat by Van Bebber’s determination and some great, almost surreal touches – like the scenes between Goose and his crazy, druggie father (Charlie Goetz) – and interesting performances from the supporting cast.

Arrow’s 2K restoration makes the movie look far more polished than it did on DVD. The disk includes a commentary, a feature-length documentary about Van Bebber’s indie career in Dayton, outtakes, an archival featurette, four of Van Bebber’s short films, a collection of his music videos, and the trailer for his unmade feature Chunk Blower.

*

Female Prisoner Scorpion Collection (1972-73)

I first came across the character of Female Prisoner Scorpion in the early ’00s when I rented a DVD of the second film in the series, Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (1972). I have a vague memory of finding it highly stylized and rather brutal, its deliberately unreal style making it distant, almost abstract, less a pulpy women-in-prison drama and more a treatise on gender inequalities in Japanese society. At the time, I didn’t go any further, so I hadn’t seen the other three movies in the series until I bought Arrow’s four-disk set in a recent sale.

I’ve seen a lot of Japanese genre movies since then and even the really extreme ones seem more accessible to me now. The Scorpion films draw on filmmakers like Teruo Ishii, for whom actress Meiko Kaji had starred in Blind Woman’s Curse (1968), and Yasuharu Hasebe, who directed her in three of the Stray Cat Rock series in 1970. Having seen Kaji in those movies, and in the two Lady Snowblood features by Toshiya Fujita (1973-74), there’s now a clear entry point into the strange world of Scorpion. Kaji has a distinctive presence as an almost silent but indomitably strong-willed woman, initially betrayed by her own emotions and subjected to relentless abuse by a patriarchal system which despises strong women; over the course of the series she becomes a kind of avenging spirit – each film begins with her brutal repression and ends with her exacting revenge on her tormentors in a liberating burst of violence.

As various commenters on the disks point out, structurally the movies bear a close resemblance to the rape-revenge sub-genre, but the stylized world in which they take place gives the character an almost elemental form. This is particularly clear in the second film, Jailhouse 41, which draws on traditions of the Japanese ghost story – there are moments as visually expressive as Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1964) – evoking a conflict between women (and female sexuality) and men which seems to stand outside of time.

In the first film, Female Prisoner 701: Scorpion (1972) – the debut feature of Shunya Ito, who directed the first three films – Nami (Kaji) is in love with cop Sugimi (Isao Natsuyagi), who callously sets her up as part of an undercover drug sting; not only is she caught up in the arrest, she’s brutally raped by the gang. Nami realizes that Sugimi is on the take, and he has used her to help wipe out a rival gang. Not being in a position to expose him, she is sent to prison where her innocence puts her at odds with the authorities and prisoners alike. Superficially this is like any number of innocent-sent-to-prison movies … but Ito’s heightened visual style transforms the prison into something like one of the circles of Hell. Nami’s resistance brings increasingly harsh punishments and turns the other prisoners against her as they become collateral damage in her rebellion…

But even as things become increasingly violent, Nami grows more iron-willed, refusing to be broken. This is the pattern for the whole series, her attempted escapes getting her out temporarily so that she can destroy the men who have inflicted this ordeal on her. By the end of the series, Nami is leading a whole movement of defiant women against the society which she despises. Each film plays variations on this central theme.

In the second film, she helps a group of women escape, but they too eventually turn against her. Jailhouse 41 is the best film in the series, at least the most evocative, with a mid-section which plunges into visual fantasy as the escaped women cross a landscape of volcanic ash and come to a deserted village where they find an old woman who illuminates each of their individual crimes (all laid at the feet of men who used or failed them) before dying in a sequence which would have fitted nicely into Kwaidan – in blazing autumnal colours, Nami covers the old woman in leaves, which are then blown away by a strong wind, leaving nothing behind.

The third film, Beast Stable (1973), begins with Nami out of prison and on the run. She holes up with a young woman who lives with her brother – a helpless man with a brain injury and an insatiable desire for sex, to which the sister submits in order to keep him calm – but is being pursued by a persistent detective. Eventually the young woman betrays her, and Nami finds herself imprisoned by a gang led by another former prisoner, a woman who despises her because of the trouble Nami used to cause inside.

The fourth movie has a somewhat different tone; new director Yasuharu Hasebe doesn’t push things as far as Ito visually, except at the very end. Once again Nami is on the outside; though she’s seized by the police in the opening scene, she escapes and is aided by Kudo (Masakazu Tamura), a former student radical. The tentative relationship between the two is a departure from the norm set up in the previous films – Nami has never needed a male protector before, in fact has been in a perpetual state of war with men. This new turn makes 701’s Grudge Song (1973) seem more conventional.

But eventually Kudo inadvertently betrays her and she’s captured, tried and sentenced to death. The relentless cop Hirose (Hiroshi Tsukata), eager for personal revenge, arranges for her escape so that he can personally hang her on a crude gallows in the countryside. This takes place at sunset, giving Hasebe an opportunity to echo the stylized visuals of the earlier films. Needless to say, Nami manages to outwit the cop and survives to continue her personal revolt against the patriarchy.

The Female Prisoner Scorpion movies at times push the extremes of Japanese genre cinema further than usual, in terms of both the visual stylization and the abuse inflicted on Nami – there are some scenes which are quite unpleasant to watch, but they never sink to objectifying her for the exploitative pleasure of the male gaze; the films adhere to her point of view, feeding the audience’s anger about what’s being done to her and stoking a desire to see her exact her just revenge against her oppressors.

All four movies have been transferred with a film-like image and each is supplemented with a number of extras (though no commentaries) – each gets a lengthy introduction by a fan, Gareth Evans, Kier-la Janisse, Kat Ellinger and Katzuyoshi Kumakiri respectively (the two women are particularly interesting as they dig into the films’ complicated sexual politics), plus new and archival interviews and featurettes about the films, the directors and star Meiko Kaji.

*

Property is No Longer a Theft (Elio Petri, 1973)

My first encounter with the work of Elio Petri was seeing The 10th Victim (1965) on television in the late 1960s. I was interested because it was an adaptation of a story by Robert Sheckley, one of my favourite science fiction writers at the time. I must have noticed the film’s style – an exaggerated pop art design suggesting the future through a judicious use of real locations and modern fashions tipped slightly into parody. I recall enjoying it, though being a bit disappointed that the story’s blackly comic satire had been rendered as something closer to light comedy.

I’m not even sure that when I saw Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970) in the early ’70s I realized that the same filmmaker was responsible. That film was one of the landmarks in my progress towards a serious appreciation of cinema, a political satire disguised as a thriller, using elements of the giallo and poliziotteschi to dissect the corruption inherent in the bourgeois state. Despite the international success of Investigation, Petri has remained fairly obscure to English-speaking audiences; barely half of his eleven features are readily available – Investigation, The 10th Victim, L’Assassino, A Quiet Place in the Country, and now Property is No Longer a Theft (1972).

Despite its heightened style, Investigation maintains a degree of cinematic realism; in contrast, Property continuously calls attention to its own artifice, breaking the frame to have its characters address the audience directly through monologues which offer (unreliable) explanations of motive and overt complaints and criticisms about the emotionally and psychologically crippling effects of Capitalism. Petri’s black comedy is a demonstration of how money and property fundamentally distort society both structurally and on the level of personal relationships. In a world where every interaction is transactional, nothing is genuine.

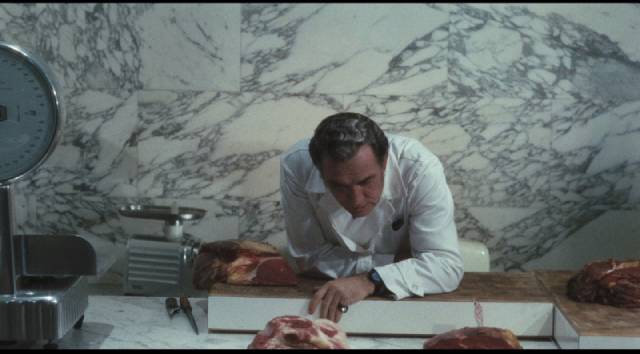

Total (Flavio Bucci) is a bank clerk who is literally allergic to money – he’s constantly scratching himself when it’s around. Having observed the power and respect afforded The Butcher (Ugo Tognazzi), who breezes into the bank regularly, handing employees choice cuts of meat in return for privileged treatment, Total goes to his boss and asks for a loan. Why? To improve his own life. What does he have for collateral? Nothing. The boss kicks him out for such audacity.

So Total embarks on a new career, targeting the Butcher (who is a crook himself), taking from the wealthy man his wealth and property – including his mistress Anita (Daria Nicolodi). The Butcher grows increasingly paranoid, his money and property becoming itself a source of deepening insecurity. Total gradually expands his criminal activity, stealing from other thieves, and disrupting the system which supports all of society.

It’s apparent that as a free agent whose criminal activity is not rational – it becomes an attack on the criminal/Capitalist foundations of society rather than an attempt to gain some wealth for himself within the rules – he is a threat to the system which everyone else benefits from. Total’s ignominious personal end is contrasted with the funeral of master thief Albertone (Mario Scaccia), at which a huge crowd listens to the passionate eulogy which asserts the essential part thieves play in holding society together – nothing would have value without the perpetual threat that it could be taken from you.

Property is No Longer a Theft begins as absurdist comedy and gathers power as it progresses, an angry, disillusioned cry in reaction to the way we have trapped ourselves inside a system which separates us from our own nature.

The excellent transfer is supplemented with interviews with actor Flavio Bucci, producer Claudio Mancini, and make-up artist Pierantonio Mecacci.

*

As an indication of the burden I experience from my disk addiction, here is a list of the Arrow releases currently waiting on the shelf – admittedly, many of these are movies I’ve seen before (some many times) and the disks are upgrades, so perhaps there’s less pressure to get to them.

Box sets:

The Complete Sartana (partially watched)

Kinji Fukasaku’s New Battles Without Honour and Humanity

George Romero Between Night and Dawn

Three Films by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani

Outlaw Gangster VIP: The Complete Collection

Takashi Miike’s Dead or Alive Trilogy and Black Society Trilogy

Jose Larraz’ Blood Hunger

DeNiro & De Palma: The Early Films

Individual disks:

Frank Henenlotter’s Brain Damage

Marco Ferreri’s La Grande Bouffe

Roberto Rossellini’s Viva L’Italia

Luigi Bazzoni and Franco Rossellini’s The Possessed

Olivier Assayas’ Irma Vep

William Friedkin’s Cruising

Roger Donaldson’s Sleeping Dogs and Smash Palace

Terry Gilliam’s Tideland

Kleber Mendonca Filho’s Aquarius

Aleksei German’s Khrustalyov, My Car

Ted Post’s The Baby

Mario Bava’s Erik the Conqueror

Marcel Ophuls’ The Sorrow and the Pity

Jorg Buttgereit’s Nekromantik 1 and 2, Schramm and Der Todesking

Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction

Geoff Murphy’s The Quiet Earth

Vincent Ward’s Vigil and The Navigator

Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist

Ulli Lommel’s Tenderness of the Wolves

Andrzej Zulawski’s Cosmos

Jack Hill’s Spider Baby

Jacques Tourneur’s The Comedy of Terrors

Peter Fonda’s The Hired Hand

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Mystery of Picasso

Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion

Buddy Cooper’s The Mutilator

Ovidio Assonitis’ Madhouse

Leszek Burzynski’s Trapped Alive

Andrea Bianchi’s Strip Nude for Your Killer

Ed Hunt’s Bloody Birthday

Carol Reed’s The Running Man

And that’s just Arrow … there are other stacks of releases from Indicator, Eureka, BFI, Severin, Twilight Time, Shout! Factory, and numerous other random distributors.

Comments