Smart Sci-Fi

With release schedules clogged by Star Wars and superhero movies, there’s always a small shock of surprise when I come across an intelligent and sometimes quirky science fiction feature which is just a thing in itself, revealing the creative personality of a filmmaker unfettered by corporate dictates. It’s all the more surprising when such a film is of relatively recent vintage, not predating the franchising of the genre. Franchise movies are dictated by prior expectations, trapped by the audiences they target, while a one-off is free to head in its own idiosyncratic directions – and thus still retain the possibility of surprise.

I recently watched four very different sci-fi movies, each of which revitalized my interest in the genre – five if you count revisiting Duncan Jones’ Moon (2009) for the first time in years … it holds up very well, though it is disconcerting to hear Kevin Spacey’s voice coming from Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell)’s robot companion.

*

Ad Astra (James Gray, 2019)

Of the four, the most conventional is James Gray’s Ad Astra (2019). Like Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014), this is a big effects-heavy space movie which puts all its technology in service to a small personal story of family dysfunction and self-discovery. But even though its elements seem familiar, Gray plays with viewer expectations and offers some unexpected twists. And as is the case with genre films in general, what matters most is not necessarily the specific ingredients, but rather the way those ingredients are treated – style and embellishment.

Earth is threatened with destruction by increasingly powerful bursts of an unknown energy emanating from the vicinity of Saturn and the authorities believe the phenomenon has something to do with an expedition which disappeared many years ago; the lost ship was powered by some kind of antimatter drive and the energy may be coming from that. A mission is planned to search for and neutralize the missing ship. (This set-up echoes Paul W.S. Anderson’s Event Horizon [1997].)

Roy McBride (Brad Pitt) is chosen for the mission because the lost ship was commanded by his father, H. Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones). While the overt aim is to save Earth, the more immediate story is about a son estranged from his father and seeking emotional closure; Roy needs to understand why he was abandoned as a boy. Perhaps the most original thing in the movie is its refusal to provide that closure, Roy instead just having to learn to accept that his personal existence was simply of no interest to a man driven by an obsessive desire to understand the whole of existence on a cosmic rather than human scale.

While there are a few big action sequences – a car chase/shoot-out on the moon; an encounter with a deep-space lab in which experimental animals have savagely turned on the researchers; the climactic confrontation in Saturn’s rings – Ad Astra is largely about stillness and contemplation. In fact, it’s the most Malick-like movie not actually made by Terrence Malick; it savours the depths of space, the contrast between the human and the infinite, and provides perspective on that contrast via a running commentary as we hear Roy’s inner thoughts interrogating his own feelings about that unresolved relationship with his father.

James Gray is one of those holes in my cinematic experience, though several friends have been recommending him to me for years. I’m not sure why I haven’t gotten around to him until now, but I’ve been told that this film is quite unlike the rest of his work. I guess I’ll have to sample some others now because I really liked Ad Astra. He balances the contrasting scales of the story well, and his evocation of the awesomeness of space is reminiscent of 2001: A Space Odyssey and Tarkovsky’s Solaris – which just makes the action scenes feel rather tacked on, as if the producers and/or distributors were worried that the film might be too intellectual for a mainstream audience without that kind of excitement.

That said, the film does start with an impressive bang: Roy is working on a vast tower which is built from the Earth’s surface up into space. Doing an inspection on the outside when one of the energy pulses strikes, Roy is thrown off as sections of the tower collapse, literally falling from space back to Earth – these workers are equipped with parachutes in case of such an accident. This is an idea I recall from reading sci-fi back in the ’60s, but have never seen in a movie before. (I also used to have a recurring dream very much like this when I was a boy – unsettling because heights make me nervous.) The sequence sets a tone of danger and exhilaration which also tells the audience that they’re not necessarily going to get what they expected.

*

Aniara (Pella Kågerman & Hugo Lilja, 2018)

By an odd coincidence, the Swedish film Aniara (2018) opens with another classic idea from science fiction literature which, as far as I know, has never been seen on screen before – the space elevator which was originally proposed, I believe, by Arthur C. Clarke. This involves a system of cables connecting an orbiting station to the ground, enabling people to reach space in giant elevators rather than rockets.

I think this is probably the first Swedish science fiction movie I’ve ever seen. They don’t seem to be very common, which makes Aniara that much more impressive – the scale is epic and the effects impressive despite not having an established tradition behind the production. To make it even stranger, it was adapted from a 1956 epic poem by Nobel laureate Harry Martinson, a more highbrow source than the pulp origins of many sci-fi movies.

Co-written and directed by Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja (remarkably, the first feature for both filmmakers), this is another contemplative work, juxtaposing the human with the cosmic. As the Earth dies from irreversible ecological collapse, the human race is abandoning the planet and moving to colonies on Mars (the rather chilling fantasy of certain real-life ultra-wealthy capitalists who’d rather waste their resources on this dream than devote them to trying to stop catastrophic climate change while we still have a chance). Thousands of people at a time are being transported on vast ships, kilometres long.

These ships are gigantic commercial enterprises, giant hotel and shopping mall complexes like today’s monster cruise ships. As much as the film has a protagonist, it’s Mimaroben (Emilie Jonsson), a kind of combination cruise director and social worker. She’s in charge of the Mima, an AI machine which can sync with people’s brains and provide rich virtual experiences which keep subjects connected to their Earthly lives to stave off the terrifying emptiness of space during the voyage to Mars. The Mima takes on much greater importance when a small piece of space debris disables the ship’s propulsion; power and life support still work, but the ship is now drifting without controls.

When the passengers are informed that there’ll be no arrival on Mars, that the ship is destined to drift into deep space indefinitely unless it manages to encounter a planet whose gravity field can catapult it back the way it came, uneasiness gradually gives way to panic. More and more people want to access the Mima to escape the growing horror. The Mimaroben does what she can, but only so many people can connect at a time. What was once a form of meditation and amusement has become a lifeline which is stretched too thin. In time, the Mima is overloaded with the dreams it has to transform into virtual experiences and finally it can’t take the emotional strain any more and in a sense commits suicide.

Days turn into weeks, weeks into months, months into years, years into decades. Society evolves, breaks down, reforms … the Mimaroben, like all other crew members, is assigned other tasks, performing menial work. The captain abdicates his responsibilities – with no control, no destination, no effective decisions to make, he becomes resentful of any suggestions which might at least alleviate the bleak state of the shipboard community. The Mimaroben comes up with a kind of replacement for the dead AI, but he forbids her to build it. She ignores him and eventually manages to project a vast holographic image around the ship – forests, waterfalls, sunsets – which at least for a while conceal the void.

In a conventional version of this story, there might be a rescue (for a while it looks as if this might happen when a small ship is detected; it takes a year to reach the “Aniara” but turns out to be an alien probe of unknown purpose), or the ingenuity of the crew or someone among the passengers would find a solution. But it never happens. Earth is gradually forgotten, religious cults form, the ruined Mima chamber becomes a kind of ritual site. And the ship drifts on … finally approaching a verdant planet millions of years later, long after all the human inhabitants have vanished.

Aniara is a slow and subtle movie, patiently observing the effects on the ship’s inhabitants of being cut off from the planet onto which they were born and which gave them a sense of identity and purpose. Powerless to control their own destiny, they gradually lose their humanity and in time can no longer sustain their existence. The evocation of the cold emptiness of limitless space throws the fragility of human life into sharp relief … and serves as a potent reminder of our ties to this planet and the urgent need to act to preserve it while there’s still time. Unlike 2001, it doesn’t offer the potential comfort of aliens watching over us; we’re on our own and responsible for our own fate.

*

The Whispering Star (Sion Sono, 2015)

Like his contemporary Takashi Miike, Sion Sono is remarkably prolific. Also like Miike, Sono’s output is very eclectic, although perhaps less rooted in profligate genre experimentation. Some of his features – like Suicide Circle and Noriko’s Dinner Table, Cold Fish and Guilty of Romance – can be as extreme as Miike’s, filled with madness and violence, but some of his best work is rooted in current situations which deeply affect Japanese society. In particular, he has returned a number of times to Fukushima and the devastating effects of the earthquake, tsunami and reactor disaster.

The shadow of Fukushima hangs over Sono’s thirty-fourth feature, The Whispering Star, the last of six films he made in 2015. This melancholy fantasy couldn’t be farther from Ad Astra and Aniara stylistically, but like them it explores the meaning of individual lives in a vast, impersonal universe. Deeply melancholy, it eschews realism in favour of evocative whimsy.

With the fragmentary remnants of humanity scattered throughout the galaxy, outnumbered by intelligent, self-aware robots, connections are maintained by couriers who take years, decades even, to deliver packages from planet to planet. One such is Yoko Suzuki (Megumi Kagurazaka), who spends her life in a small spacecraft, the ship’s computer her only companion. Following an unwavering daily routine of cleaning, eating, doing laundry and making cups of tea, Yoko has little to do between stops, although she does have to analyze and fix an issue with the navigation computer (it becomes confused between inside and outside and begins making course corrections based on the movements of insects picked up at the last stop, reading their activity as a meteor shower).

The ship itself signals Sono’s intention to make an allegory rather than realist science fiction: it is like a cross between a boxcar and a house trailer, largely constructed from wood, with a sparse interior containing little more than the computer, a stove and washing machine, and a storage area at the back where the packages are stacked. For a very long first act, we are trapped on the ship with Yoko, watching her mundane routines – for company she digs out an old tape recorder and listens to an audio diary she has kept for years, her observations about the same daily routines we are watching. This seems like an empty and pointless existence, but being a machine, she appears unperturbed; boredom is a meaningless concept, these endless days merely the pauses between the brief moments when her work suddenly becomes poignantly meaningful.

These are the moments when she lands on some remote planet and walks to a rendezvous carrying a cardboard carton to be delivered to a customer. These customers are few and far between, living in desolate areas full of collapsing buildings overgrown with weeds. All these planets were shot in the Fukushima area, abandoned for years, gradually being reclaimed by nature. The people Yoko encounters are mostly played by residents of the area, living amongst the ruins of their pre-disaster lives. Isolation and loneliness fill these characters with a passive fatalism, or in some cases delusion and madness. The sense of emptiness is amplified rather than alleviated when the contents of the packages are revealed – mostly odd scraps with no intrinsic value, but obviously of some cryptic personal significance, secret messages being passed from one isolated person to another, sometimes taking years to arrive and remind someone of a long-unseen relative or friend. With the human race scattered and dying out, these fragile signs of lingering connection assume a deep air of melancholia.

Towards the end, the film becomes even more abstract and symbolic; Yoko, searching for a customer, walks along translucent hallways where we can see many people in silhouette, engaged in shadow plays of family life, of romance, eerily evocative of the shadows burned into the walls of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the annihilating heat of the atomic bombs, traces of lives passing into nothing.

The Whispering Star is a visual ode to entropy, the winding down of the human presence in a vast empty universe – the end of our brief reign brought about by a mixture of natural disasters and our own inability to sustain a sense of meaning. Like Aniara, it depicts what happens when we try to abandon the home we have ruined only to find that we can’t survive separation from the place which gave birth to us.

*

Sleep Dealer (Alex Rivera, 2008)

Working on a small budget, a sci-fi filmmaker has – broadly speaking – two main options: he or she can go the exploitation route, adhering to well-established genre tropes in hopes of attracting a pre-existing (and often undemanding) audience; or conversely, she or he can, given the modest financial risk, aim for something more original, something which doesn’t rely on audience expectations. The latter, needless to say, is the more challenging prospect.

First-time feature director Alex Rivera, with the help of the Sundance Institute, took the latter course, using the genre to project current trends into the near future, coming up with a remarkably prescient movie called Sleep Dealer (2008). This small Spanish-language film somehow escaped my notice for twelve years despite favourable reviews and a bunch of festival awards; I came across a used copy recently while trading in some DVDs at a local store. The packaging caught my attention with interesting graphics and a couple of enthusiastic quotes from WIRED and A.O. Scott at the New York Times. Such quotes are never sufficient in themselves, being too easily manipulated, but the description on the cover made it seem worth a chance.

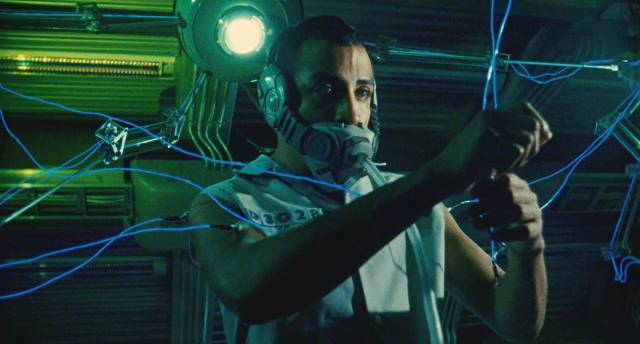

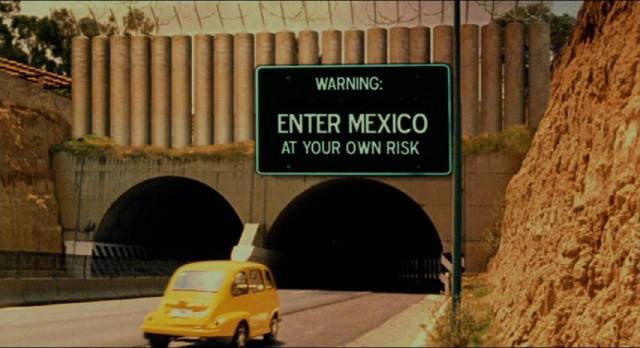

Not only did the movie live up to those quotes, Sleep Dealer turns out to be a terrific combination of character, intelligent projection of politics, economics and technology, and resonant emotional engagement. Although made before the election of Barack Obama, the film gives us the all-too-probable future of Trump-world. The U.S.-Mexico border has been sealed with a wall, but Capitalism has found a way to get around the loss of cheap labour; along the border are “factories” where workers equipped with sockets in their arms and backs connect to a network which enables them to control machines in the States. Barred from the country, they continue to do the manual labour they once illegally crossed the border for. The U.S. economy benefits while xenophobes get their way by blocking illegal immigration.

But this is just one aspect of Rivera’s astute projection. While people are restricted and exploited, the corporate control of government and the economy extends even more powerfully beyond borders than it does today. Private companies have appropriated resources like water, damming rivers and forcing farmers to buy at exorbitant prices in a desperate effort to keep crops growing on parched patches of land. These dams are protected by complex surveillance systems which include remotely controlled guns mounted around the reservoirs as well as armed drones controlled from locations in the States.

In a small, dry Mexican village, Memo Cruz (Luis Fernando Pena) can see no future in the small farm worked by his father. He wants out, though options are limited. He spends his time building a makeshift communications system which connects him to the outside world. But as he makes it more powerful, it’s detected by the corporation which controls the local dam. One day, in town, Memo sees a live broadcast on a television in a store: a flashy reality show from the States offers viewers the real-time experience of watching a drone take out a “terrorist”. Memo watches in horror as the drone closes in on his village, and finally on his father’s house. As his injured father crawls from the missile strike, the implacable drone, piloted by a man in San Diego, fires again, vaporizing him.

Having set up this bleak political and economic system, Rivera shifts decisively into a personal story which displays both the terrible impact of the system on individual lives and the ways individuals find to push back – making personal connections with one another and subverting the power of the corporate state.

Heading for the border and the factories, Memo meets a woman on the bus. Luz Martinez (Leonor Varela) shows an interest in him without revealing much about herself. He notices nodes on her wrists and she gives him advice on how to get implants so he can find work, but she has an ulterior motive. Luz is a “writer” and back in Tijuana she plugs into the net and uploads her memories of Memo, prompted by the computer to be more personal and add her feelings to the memory recording.

Until now, Luz has had no luck selling her memories, but this one finds a paying customer who offers to buy further recordings of Memo. She tracks him down – his first attempt at buying black market nodes ended with him being robbed – and she offers to install the nodes herself, making herself an active part of his story, which she’ll upload in instalments as he finds work, finds an empty shack on the edge of town to squat in, and begins the exploited life of a node worker. Plugged in, these workers are slowly consumed by the machines, minds and bodies drained, discarded, and replaced by others ready to sell themselves – many like Memo doing it for money to send back home to support desperate families.

As Luz “writes” Memo’s story she uncovers what happened to his father and his deep guilt for having unwittingly caused it. It turns out that her subscriber is Rudy Ramirez (Jacob Vargas), an immigrant to the U.S. who has the prestigious and well-paying job of drone pilot. Through Luz’s posts, he discovers that his first kill was not in fact a terrorist threatening his employer, but actually just an old peasant farmer. He heads back across the border in search of Memo.

These three lives gradually intersect and intertwine, Rudy determined to make amends and in the process assuaging, to some degree, Memo’s guilt and healing the rift which occurred when Memo discovered that Luz had been using him and his life for her own profit. Together, the three of them forge close personal bonds which restore a humanity which the system has deliberately stripped away to facilitate corporate profit-making. And this shared humanity becomes the means by which they turn the power of the corporation against itself.

*

Ad Astra, not surprisingly, looks very good on the Fox/Regency Blu-ray. Shot on a combination of 35mm and digital cameras, the image has some texture and the effects are well-executed. The disk includes a collection of brief featurettes on the actors and production design, some deleted scenes and a commentary from director James Gray.

Aniara is available on Blu-ray from Magnolia in region A and Arrow in region B. I assume the image quality is comparable – which means it’s excellent in both editions. The big difference is in the extras. Magnolia has just three very short interview clips with the production designer, sound designer, and effects supervisor (2-3 minutes each), while the Arrow includes those clips plus a 12-minute featurette with directors Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja and actor Arvid Kananian (who plays the ship’s captain), a commentary from Kågerman, Lilfa and Kananian, plus a 31-minute short by Kågerman and Lilja called The Unliving (2010), a bleak, open-ended story about society adapting to a post-zombie-apocalypse world.

The Whispering Star makes no attempt at conventional realism; there’s a theatrical quality to its crisp black-and-white imagery, not simply in the lengthy sequences aboard the ship and the shadow-play final sequence, but even in the locations representing the various planet surfaces, eerily abandoned, populated sparsely by ghostly figures acting out a kind of simulation of life. The region B Third Window Films Blu-ray includes a feature-length documentary by Arata Oshima, The Sion Sono (2016), which is both a making-of and a portrait of Sono as artist, something of an outsider to the Japanese film industry.

The Maya Entertainment Blu-ray of Sleep Dealer has an image which doesn’t conceal the film’s low-budget origins. It is unpolished, grainy, and the occasional CG effects (the drones and construction robots) look a bit cartoonish, but the use of gritty locations grounds the narrative in a convincing reality. There’s a commentary from director Rivera, and a short featurette in which he discusses the origins of the project.

Comments

Oddly, I’m downloading the 1960s version of Aniara while I type this. Hope to watch it tomorrow.

Funny you should say that … I’m doing the same as I reply!