One of these things is not like the others

I was a fan of science fiction and fantasy from an early age. Anything which had any element of imaginative projection appealed to me, a taste which for a long time was unfiltered by any degree of critical analysis. The flaws of something like Steve Sekely’s Day of the Triffids (1963) didn’t matter because it visualized a story I had already read and loved. The spectacle of Andrew Marton’s A Crack in the World (1965) swept me away, as did Don Chaffey’s Jason and the Argonauts (1963) and Nathan Juran’s First Men in the Moon (1964). I had a taste for disasters and the threat of annihilation; even as an adolescent I was hooked on political thrillers, usually seen on television – John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and Seven Days in May (1964). This mixture of spectacular possibilities and potential doom may well have been rooted in an unconscious absorption of the pervasive fear of nuclear annihilation into which I was born. It was in the air I breathed as a child and watching that fear being played out, or conversely denied in futuristic fantasies, was no doubt a form of social therapy and catharsis.

*

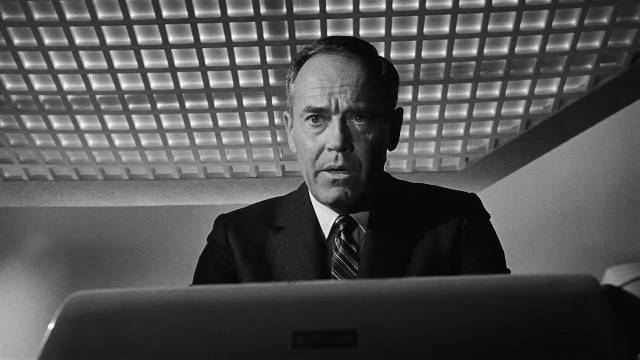

Fail-Safe (Sidney Lumet, 1964)

I saw Sidney Lumet’s Fail-Safe (1964) sometime in my early teens, not long after I’d read the novel by Eugene Burdick and Harvey Wheeler. It was no doubt lucky that I got to see it before Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (also 1964), which I first saw a few years later. The two films, made virtually simultaneously, with many plot similarities, both expressed the mood of the times in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis, but were worlds apart in style and tone, and Lumet’s movie has lived in Kubrick’s shadow since even before its release.

For me, an initial appreciation of Fail-Safe was greatly diminished after my first viewing of Dr. Strangelove. Kubrick’s film is exhilaratingly cinematic, while Lumet’s seems very much like a throwback to the days of live television drama, with its cramped sets and focus on dialogue, often shot with a static camera – though Lumet occasionally punctuates the air of a recorded play with startling editing effects, in particular in the scenes between Henry Fonda and Larry Hagman as the President and his translator.

But mainly it was Kubrick’s fanatical attention to detail, giving Strangelove a horrifying and visceral sense of realism despite the grotesquely comic exaggeration of the characters, which gave his film a more powerful impact. He captured the inherent madness of the Cold War’s defining strategy of Mutually Assured Destruction, while Fail-Safe seemed trapped in a past which was no longer viable – it has a humanistic outlook in which decent men try their best to make the right decisions. But in a world dominated by MAD, “right decisions” were no longer possible. Civilian and military leaders alike were trapped in a system which had been arrived at step by step through seemingly rational choices, though these steps were in fact mad from the beginning.

Watching Fail-Safe again for the first time in years, on Criterion’s Blu-ray, I regained something of my long-ago appreciation. Yes, it often feels like a filmed play rather than a movie, but its focus on performance is its strength. The cast is excellent and the characters’ commitment to an outmoded morality takes on a deep melancholy which exposes the terrible human flaw of being unable to comprehend the consequences of our decisions until its too late. We are doomed by our own shortsightedness (a problem on full display for years now in our failure to deal with climate change, and more recently with the Covid-19 crisis).

As cinema, Fail-Safe still falls short of Strangelove, but Lumet’s sadness at our failures is more moving than Kubrick’s savage contempt. There are numerous parallels between the films: an unforeseen occurrence sends American bombers into Russia; in an attempt to prevent catastrophe, the American President contacts the Russian Premier and, after convincing him that this is not an act of war, has the U.S. military cooperate with the Russians in bringing down the bombers; all the protocols developed to “control” nuclear combat work against these efforts to stop the accidental attack.

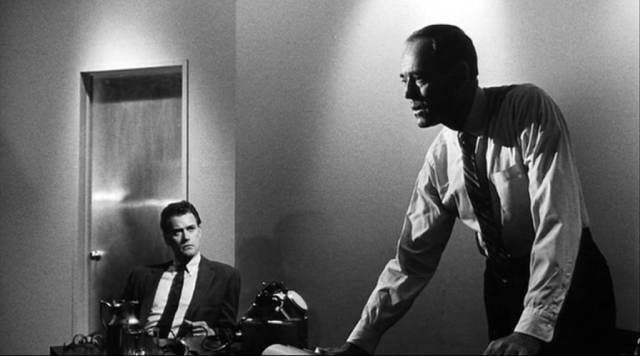

Both films take place in three primary locations, two of them shared: on board the attacking aircraft, in the American War Room. The third in Strangelove is the SAC air base, while in Fail-Safe, it’s a small featureless room occupied by the President and his translator as they maintain contact with the War Room and Russians by phone. In Kubrick’s film, the War Room and the base are sites of chaos, while the plane is a locus of calm professionalism. Calm professionalism rules throughout Fail-Safe, making the failures more subtly depressing – rather than nihilistically exhilarating.

One of the more interesting points of coincidence between the two films is the presence of a German character who is completely invested in the idea of nuclear war. In Kubrick’s film, of course, this is Dr. Strangelove himself, a man whose own body is at war with itself, the embodiment of a gleefully embraced self-destructiveness. In Lumet’s film, it’s Kissinger-like national security advisor Dr. Groeteschele (Walter Matthau), who combines Strangelove’s belief in the inevitability of war with General Turgidson’s belief that, although it has been triggered unintentionally, there’s no choice but to commit fully and obliterate the world.

With all these similarities, it’s not surprising that lawsuits were filed. Despite the fact that the two films were based on two separate novels – Peter George’s 1958 Red Alert for Strangelove and Burdick and Wheeler’s 1962 Fail-Safe – Kubrick and Columbia filed for copyright infringement, the case ending up with Columbia acquiring distribution rights for Lumet’s movie and holding its release back for months after Strangelove appeared in theatres; despite good reviews, Fail-Safe suffered financially – because of the similarities, but also because its tone was less well suited to post-Cuban Missile Crisis paranoia.

With the current state of the world, Strangelove’s madness seems less funny, while the sober decency of Fail-Safe’s characters now seems almost comforting – no matter how awful the disasters we face might be, it would be nice to believe that those in charge were at least doing their best even if events are beyond their abilities to control. Unfortunately, the real world today is more reflective of Kubrick’s dystopian nightmare.

Sony’s 4K restoration looks excellent on Criterion’s Fail-Safe disk, with fine detail and pleasing grain giving it a strong film-like texture. The increased definition, however, does expose the weaknesses of Lumet’s use of stock footage for the aircraft footage. Not only did the Defence Department refuse to cooperate with the production, they also blocked suppliers of stock footage from providing any material. The production managed to scrounge just a handful of shots from various sources, which are used over and over again, using optical zooms, reframes, horizontal flips, and most distractingly for some reason printing in negative. All this manipulation makes these shots excessively grainy and murky.

A director’s commentary and brief retrospective documentary (16:01) are carried over from the old DVD, and Criterion have added an interview with critic J. Hoberman, who talks about the Cold War paranoia movies of the period (19:30). There’s also a text essay by critic Bilge Ebiri.

*

Bargain basement time travel

Although I didn’t see Fail-Safe at the time of its release, I did see one of a pair of sci-fi thrillers made by Franklin Adreon in an actual theatre in its original run in the mid-’60s. These low budget movies were made towards the end of a long career in B-movies, serials and television. I must have seen numerous series episodes directed by Adreon without any awareness of who he was, but that one theatrical experience stuck with me for some reason, and I enjoyed revisiting the movie recently thanks to Kino Lorber’s unexpected Blu-ray release.

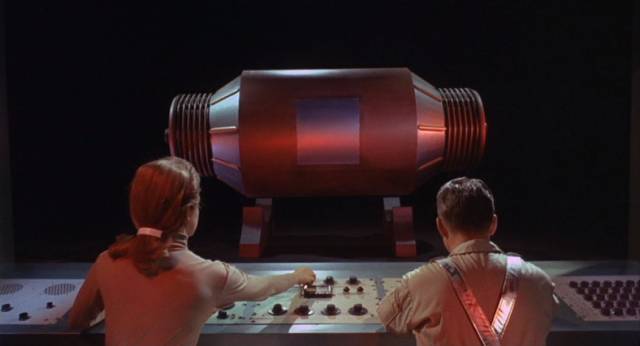

Cyborg 2087 (1966) is, to put it kindly, extremely derivative. Not only does it look like something made for TV, it borrows heavily from series like The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits. It’s a time travel paradox story in which a cyborg from the future is sent back to 1966 to prevent a scientist developing technology which will allow the government to control everyone’s thoughts. The future he comes from is a fascist police state, something the scientist – who of course only wants to help mankind – cannot foresee.

Much of the film takes place in a derelict backlot western town, and the cyborg gains some human feeling through contact with the scientist and his female assistant. The local cops are trying to stop the visitor whose motives and actions they can’t comprehend, while the future authorities have sent some killers back to stop him because they very much understand his motives and actions.

Adreon keeps the threadbare story moving, but the most notable thing about the movie is its cast. Old-timers Eduard Franz, Wendell Corey and Harry Carey Jr mix with familiar TV faces Warren Stevens, Adam Roarke and John Beck, with a brief appearance by Jo Ann Pflug in the opening scene in the future, and Karen Steele from Star Trek’s “Mudd’s Women” episode as the scientist’s assistant. But what gives this scrappy little movie a touch of unexpected class is the presence of Michael Rennie as the cyborg, recycling The Day the Earth Stood Still’s Klaatu, once again trying to save humankind from its own misguided instincts.

Kino’s disk has a decent image; the only extra is a commentary from Chris Alexander, who I gave up on long ago because of his irritating tendency to sneer at the movies he’s talking about.

Perhaps I enjoyed watching Cyborg 2087 again after more than five decades because I had fond memories of that original theatrical encounter – I saw the movie before I’d seen the two Harlan Ellison episodes of The Outer Limits, “Soldier” and “Demon With a Glass Hand” or “The Man Who Was Never Born” written by Anthony Lawrence, and long before I saw James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984). But I was a little less engaged by Adreon’s Dimension 5, apparently released simultaneously with Cyborg 2087 in October 1966. The main issue may simply be that this one is more ambitious and the low budget simply wasn’t equal to those ambitions; it’s an attempt to do a Bond-like thriller with time travel thrown in.

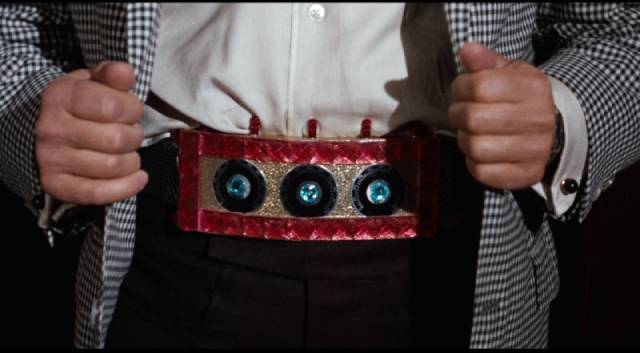

That sci-fi element is pretty perfunctory. A device developed by a U.S. intelligence agency enables agent Justin Power (at least they didn’t call him Justin Time) to bounce back and forth for anything from a few seconds to several weeks. In classic form, this is used not to get around danger entirely, but rather to make hair’s-breadth escapes as the bad guys’ bullets fly.

When word comes that sinister oriental Big Buddha (Harold Sakata who had played Oddjob in Goldfinger a couple of years earlier) plans to destroy Los Angeles with a nuclear bomb, Power (Jeffrey Hunter) is assigned a new partner, Kitty (France Nuyen), who has ulterior motives for getting involved which at times make her loyalties suspect. The pair jump ahead to uncover how the bomb is being imported and figure out how to foil the attack.

The best thing about Dimension 5 is the gaudy ’60s colours and decor; on a narrative level it’s more Matt Helm than James Bond and the limited use of the time travel device is disappointing – it could have been dropped entirely without really affecting the story.

Once again Adreon managed to secure a better cast than you’d expect. In addition to Sakata and Nuyen, Donald Woods and Robert Ito show up, while Jeffrey Hunter (recently appearing as Captain Pike in Star Trek’s two-part “The Menagerie”, recycled from the rejected original pilot) valiantly plays Power as if his best days were not already some years behind him.

Kino’s disk sports a colourful transfer and a group commentary by (strangely) the staff of Atlanta’s only remaining video rental store.

Comments