Pandemic viewing, Part Four

Although my viewing keeps racing ahead of my ability to make comments here, this is the fourth and last post rounding up what I’ve seen in the first six weeks of lockdown. As previously noted, I’ve been leaning heavily on undemanding genre fare instead of making use of this time to explore all the great cinema I have untouched on my shelves … not sure what, if anything, that means.

Vinegar Syndrome

For some reason – mostly some recent enticing sales – I’ve been watching a lot of Vinegar Syndrome disks. This is a company that’s been around for a while, but which I mostly ignored until a year or so ago. Their earlier releases tended towards sleaze and actual porn, but they’ve been expanding their catalogue to include a lot of low budget, independent horror from the 1970s and ’80s, and even some higher quality, more experimental films like Muscha’s Decoder (1984).

Nightbeast (Don Dohler, 1982)

I’ve known about Don Dohler for forty years, but hadn’t seen any of his movies until a couple of weeks ago. Back in the ‘70s he published a special effects how-to magazine called Cinemagic. Although it was aimed at do-it-yourself filmmakers, it had articles by and about professionals like Craig Reardon, Ben Burtt and Dick Smith. But its target audience was people like Dohler, making super-8 and 16mm features in their backyards with the help of friends. I still have a copy of Film Magic, the slim book Dohler edited in 1979 from the accumulated material he’d published over the past decade. I also have the first ten issues of the more professionally produced Cinemagic put out in 1979-80 under the Starlog banner. What Dohler lacked in talent, he made up for with enthusiasm … that kind of gung-ho “let’s put on a show” attitude Hollywood used to make musicals about. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that, like John Waters, he hailed from Baltimore. Nightbeast (1982) was the third of seven features he made between 1978 and 2007 (the last released posthumously). Like most of them, it’s about a small town/suburb which falls prey to a murderous monster, an alien which crash lands in the woods and sets about slaughtering everyone it meets for no apparent reason. Acting is basic, effects aren’t bad considering the budget, narrative is perfunctory, but Dohler at least manages to make it look like an actual movie (I’ve seen other backyard productions which couldn’t be saved by any amount of amateur enthusiasm). The 2K scan is as good as you could expect given the source. There’s a blooper reel, an archival commentary, and several interviews with people involved in the production.

Blood Harvest (Bill Rebane, 1986)

What Don Dohler did for Baltimore, Bill Rebane did for Wisconsin. Rebane was another low-budget regional filmmaker, though from the one film of his I’ve seen, he appears to be more technically polished, though lacking in Dohler’s goofy charm, and he could afford to hire name actors obviously on the downslope of their careers. Blood Harvest (1986), a fairly generic slasher, interested me for one reason: the presence of eccentric performer Tiny Tim in a supporting role. Tiny seems to have stepped in not just from another movie, but from another world entirely. As Mervo, he wanders around dressed as a clown, muttering to himself and spying on the heroine, traumatized from having found his parents dead after they lost the family farm to the bank. The heroine, Jill (Itonia Salchek), just arrived back in town, is the daughter of the local bank manager, hated by everyone for destroying so many farmers’ lives with foreclosures. Jill finds her family home vandalized and her parents vanished. The sheriff is no help, but a solicitous childhood friend, Mervo’s brother Gary (Dean West), tries to be helpful. With bodies piling up, it’s not much of a mystery who the killer is … but it takes a long time to get there. Salchek, in her only movie role, is actually quite good as the heroine; Tiny Tim is a fascinating spectacle; but the movie is irritatingly sloppy (people disappear, leaving their cars in the driveway, and people keep wondering where they are, must’ve gone to town … you want to yell at the screen for them to look out the window and see the damn car parked there). The scan’s not bad, there’s a commentary with producer Leszek Burzynski, who two years later directed the more interesting Trapped Alive, and some archival material with Tiny Tim – a brief impromptu interview and a 71-minute(!) performance and chat.

Secta Siniestra (Ignacio F. Iquino, 1982)

Here’s something new and unexpected – a Spanish horror movie made by a 72-year-old filmmaker near the end of his career. I hadn’t heard of Secta Siniestra (aka Bloody Sect, 1982), or director Ignacio F. Iquino, before finding this disk in the listings of an on-line sale, but I’m always interested in poking around in the unfamiliar crannies of film history, so I ordered a copy. It starts with a bang – Frederick (Carlos Martos) and his mistress Helen (Emma Quer) hop into bed, while upstairs the maid is taking dinner to his insane wife Elizabeth (Diana Conca), who’s locked in the attic. Liz beats the maid up and escapes, finding the sated couple asleep after sex; she uses a two-pronged fire poker to stab Fred in the eyes. With him blind, and Liz locked in an asylum, Helen insists on marrying Fred even though he thinks he’s useless. Turns out he’s also sterile, so they go to a fertility clinic to get Helen pregnant. Unfortunately, it’s run by a Satanic cult – you can guess who the donor was – and Helen, fighting really bad morning sickness and unwholesome cravings, finds herself both intimidated and protected by the cult as she carries the devil baby to term (previous attempts by the cult have ended in madness and suicide). Secta Siniestra is what we would have called back in my childhood “cheap and cheerful”, a chaotic mix of derivative elements thrown together without much conviction or style, climaxing in a jaw-dropping moment when the baby is revealed … I guess the budget had completely run out by then. Still, the movie is packed with absurdities and overwrought performances, which gives it some entertainment value. The transfer looks good and the disk even sports a Kat Ellinger commentary.

Shot (Mitch Brown, 1973)

This low-budget regional action-drama isn’t particularly original – a couple of cops try to bring down a local drug kingpin who’s violently expanding his business – and performances are okay within the limitations of the production. But when you know that it was made by a couple of university students for about $15,000, it suddenly becomes much more impressive. It has action scenes, it has car chases, it has some really nice, extensive aerial footage … while working within genre limitations, director Mitch Brown and producer Nate Kohn show some real ambition. Strange, then, that Brown never directed another film, while Kohn has had a spotty producing career (after this he produced Douglas Hickox’ Zulu Dawn in 1979, and then a few seemingly random credits in the 2000s). What Shot lacks in narrative originality, it makes up for in visual detail (a fine use of locations) and quirky character bits that would probably be considered extraneous in a more commercial project. What’s even more surprising is the quality of the transfer, a 2K scan from the original 16mm reversal stock, with a film-like texture and good colour rendition. There are interviews with both Brown (on camera) and Kohn (audio only) on the disk.

in Juan Antonio Bardem’s The Corruption of Chris Miller (1973)

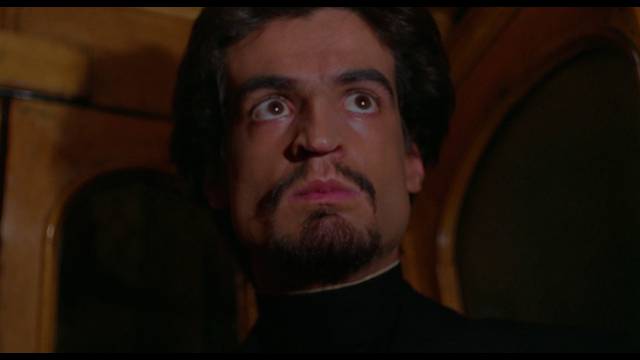

The Corruption of Chris Miller (Juan Antonio Bardem, 1973)

My only previous encounter with the work of Spanish director Juan Antonio Bardem was the excellent Death of a Cyclist (1955), a dissection of bourgeois privilege and guilt in Franco’s Spain. Bardem was a communist providing social commentary through melodrama and the tropes of a psychological thriller. The Corruption of Chris Miller (1971), made near the end of Franco’s regime, seems less informed by social critique and more influenced by the giallo. It begins with a brutal murder by a man wearing a Chaplin mask, then shifts to a country house inhabited by Ruth Miller (Jean Seberg) and her stepdaughter Chris (Marisol). Their relationship is strained for reasons not immediately clear, though it has something to do with their having been abandoned some years earlier by Chris’ father. Anger, jealousy and who knows what else is bubbling below the surface. Then a drifter turns up, having taken shelter in the barn from a storm (it rains a lot in this region). An Englishman named Barney Webster (Barry Stokes, who played a similar role four years later in Norman J. Warren’s Prey), he’s hitching his way around Spain and, according to television reports, bears some resemblance to the serial killer operating in the area. Barney plays the two women off against one another, igniting sexual tensions, and eventually they join forces and turn against him. It’s only just after they’ve savagely killed him and disposed of the body that they learn that the actual serial killer has been caught … leaving the two women now bound by guilt in an even more complicated relationship. With a 4K scan of the original negative, the disk has an impressive image, with both English and Spanish soundtracks (the former preferable, with Seberg’s and Stokes’ actual voices; Marisol is dubbed, but obviously spoke her lines in English so sync is good). There’s a one-hour television interview with Bardem, a 12-minute featurette which packs in a lot of information about Seberg’s life and career, and an alternate Spanish ending, which is actually more satisfying than the contrived ending of the English-language version.

in Robert Hartford-Davis’ Beware My Brethren

Beware My Brethren (Robert Hartford-Davis, 1972)

Robert Hartford-Davis didn’t have a particularly discernible directorial personality – his output was rather random, beginning with minor British crime films and comedies in the early ’60s and ending with a couple of blaxploitation movies in the early ’70s in the States – which may be why he’s most closely associated with several horror films from the middle of his career, though they didn’t garner much critical appreciation at the time: The Black Torment (1964), the surprisingly sleazy Corruption (1968), the disastrous mess Incense of the Damned (1971), and the last and definitely best, Beware My Brethren aka The Fiend (1972). A decidedly grubby little piece about religious hypocrisy, madness and murder, it would make a fine double bill with Pete Walker’s House of Mortal Sin aka The Confessional (1976). A fanatical Christian preacher (Patrick Magee) holds his flock in a state of abject terror of damnation, including Birdy Wemys (Ann Todd) who has provided her house for the sect’s chapel. Birdy is frail – in fact, she’s a diabetic who has to hide the fact that she gets regular insulin injections because any kind of drug is an abomination before the Lord. Birdy was abandoned by her husband and clings to the sect; her relationship with her son Kenny (Tony Beckley) is extremely warped. She’s filled him with guilt and a horror of sex to the point where any attraction he feels triggers a murderous impulse towards young women. The atmosphere is thick and diseased, Kenny’s brutal sex crimes amplified by intimations of incestuous desire between mother and son. The 2K scan from the original negative supplies an excellent, textured image and the mono sound is fine, with some real force during the sect’s meetings in which everybody calls out forcefully to the Lord and one woman (Maxine Barrie) belts out hymns – these musical moments are disorienting because, while on-screen the singer is accompanied by Birdy on a small organ, what we hear is a very full band with a gospel-jazz sound. Somehow this odd stylistic choice actually works, suggesting the emotional appeal of the preacher’s message to the members of the congregation. There’s a commentary from Samm Deighan and a brief featurette comparing the UK cut with the longer international edit which has a bit more gore.

*

Kino Lorber

4D Man (Irvin S. Yeaworth Jr, 1959)

Irvin S. Yeaworth Jr was an interesting character. Working mostly in Pennsylvania with producing partner Jack H. Harris, he made five features between 1956 and ’66, bookended with stories about youth, crime and drug addiction. He went on to direct hundreds of industrial and religious films, produced television specials for Billy Graham, led tours to the Holy Land and designed theme park attractions. But what he’s best-known for to movie fans are his three science fiction movies, beginning with his second feature, The Blob (1958), and ending with Dinosaurus! (1960). Between the amorphous alien jelly and the revived dinosaurs and caveman, he made the more adult 4D Man (1959) in which a scientist experiments with the idea that because all matter contains a lot of space between atoms, it should be possible for one object to pass through another. He succeeds, using powerful magnetic fields, but accidentally gives himself the power to walk through walls. Of course, it’s not long before he’s robbing a bank and stealing jewellery … and not much longer before he discovers that this new power is rapidly aging him as it burns up his life energy. But not to worry – he can regain some of that energy by sucking it out of other people, leaving shrivelled husks behind. Yeaworth directs this typical ’50s “there are things we’re not meant to mess with” thriller efficiently, in vibrant colour, with decent effects, and the cast (Robert Lansing, Lee Meriwether, James Congdon) treat it all with appropriate seriousness.. If it lacks the reputation and recognition value of The Blob, it’s only because of the more conventional material – it’s still a fine example of the genre. The disk looks great with a 4K restoration from the original negative, and there are two commentaries (Richard Harland Smith and Kris Yeaworth, the director’s son) and two interview featurettes, with co-star Meriwether and producer Harris.

Supernatural (Victor Halperin, 1933)

So much of Poverty Row production was dull and formulaic that it can still be a surprise when something of value emerges from the swamp … and yet, it’s probably not that strange. The people who ran those threadbare studios didn’t really care that much what came down the conveyor belt so someone with a bit of talent could get away with quite a lot creatively as long as he kept within the minuscule budget. That’s how Edgar G. Ulmer could make Detour (1945) and Frank Wisbar Strangler of the Swamp (1946). Easily the equal of both those modest masterpieces was Victor Halperin’s White Zombie (1932), which also had the distinction of launching a new genre. His follow-up isn’t as well-known, perhaps because it’s not as visually rich, nor as surprisingly poetic. But Supernatural (1933) is definitely a distinctive oddity, a very small movie with a couple of lead performers – Carole Lombard and Randolph Scott – on the cusp of stardom. White Zombie scriptwriter Garnett Weston here jams so many elements into a brief running time that much of the movie feels like a protracted set-up. There’s a condemned woman sentenced to death for murdering several lovers; there’s a doctor who believes that a killer’s malevolent spirit escapes at death and infects others; there’s an heiress whose twin brother was recently murdered; there’s a phony medium who tricked the murderess and now sets up a fake seance for the heiress to contact her dead brother; the doctor has appropriated the executed woman’s corpse for his experiments; at the seance the heiress becomes possessed by the killer’s spirit and sets out to get revenge on the medium … all in one brief, paradoxically leisurely hour. The cast and the overstuffed narrative make Supernatural entertaining, but it’s not as memorable as White Zombie. The 2K transfer shows some print damage, but the image is sharp, with excellent contrast. There’s a Tim Lucas commentary which I haven’t listened to yet.

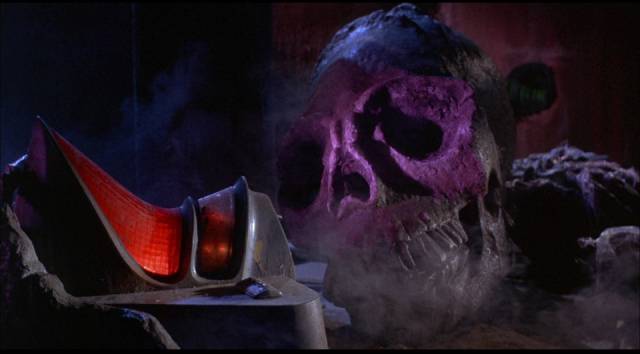

Mario Bava

Speaking of Tim Lucas, he turns up not surprisingly on three Mario Bava disks from Kino Lorber which I recently watched – all Blu-ray upgrades of movies I’ve seen many times before. Blu-ray was made for filmmakers like Bava, whose stylistic flourishes (and excesses) benefit from the increased information in the image. Both Planet of the Vampires (1965) and Hercules in the Haunted World (1961) feature Bava’s eye-popping colours – naturalism be damned – but The Whip and the Body (1963) seems problematic, with a transfer so dark that much of the film seems murky and indistinct. It’s kind of uncomfortable to watch, with far less image detail than the earlier DVD. That’s a pity, as it’s one of Bava’s most lushly perverse movies, a moody Gothic steeped in sado-masochism, with Daliah Lavi’s heroine helplessly in thrall to Christopher Lee’s contemptuous villain to the point where she brings back his ghost after he’s been killed for yet more abuse. Planet of the Vampires is a marvel of low budget ingenuity, conjuring an alien planet out of nothing but a few Styrofoam rocks and plenty of glass mattes and colour gels, providing a template for Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) with some very specific visual reference points. Hercules, presented in three separate versions – Ercole al centro della terra, the longer Italian-language cut; the slightly shorter US Hercules in the Haunted World; and the even shorter UK Hercules in the Centre of the Earth – really goes to town once the hero (Reg Park) enters the Underworld to battle villain Lico (Christopher Lee), who commands an army of the undead. In addition to the three versions, there’s a Tim Lucas commentary on the long version, plus an interview with co-star George Ardisson; the only extras on the other two disks are the Lucas commentaries.

*

Miscellaneous

Big Fish & Begonia (Xuan Liang & Chun Zhang, 2016)

I found this Chinese animation visually gorgeous but ultimately irritating. I never really got a handle on the rules of its fantasy world – Chun lives in some kind of spiritual dimension; as some kind of initiation, she and the other kids transform into red dolphins and pass through a vortex, coming out in the ocean of the human world. They’re not supposed to interact with humans, but are there to … learn something? She’s spotted by a young man and when she gets caught in a net, he cuts her free, but she panics and he drowns, leaving a little sister crying on the shore. Back in her own realm, racked with guilt, she breaks the rules by going to someone with some kind of spiritual powers and trades half her life in exchange for bringing the young man back … in the form of a tiny fish, which she has to hide as he grows. All this has upset the balance between the two worlds and disaster strikes; her realm begins to flood, people are dying … and when some way is finally found to restore balance and she decides to return to the human realm to be with the young man, she keeps turning back to say goodbye one more time … and yet another time … and it starts to feel like the end of The Return of the King … just get on with it for god’s sake! As I said, the Shout! Studios Blu-ray looks spectacular, and there’s a short film and making-of included.

The Hills Have Eyes Part 2 (Wes Craven, 1984)

Wes Craven started his career with a bang, writing and directing Last House on the Left in 1972. It was five years before he followed that up with the even better The Hills Have Eyes (1977)., then for the next three decades, he was on a rollercoaster travelling between mediocrity and decade-defining hits – A Nightmare on Elm Street in the ’80s, Scream in the ’90s and the excellent non-horror thriller Red Eye in the ’00s. In a slump in the early 1980s after Deadly Blessing and Swamp Thing and just before Nightmare, he was talked into returning to his roots by making a sequel to The Hills Have Eyes. The result was not a success and has long had a really lousy reputation … which is to some degree deserved. Given a different title and director, The Hills Have Eyes Part 2 (1984) would have been accepted as a routine ’80s slasher, but it had a reputation to live up to and fell very far short. The original rises almost to allegory with its to-the-death conflict between a complacent middle-class family and a monstrous underclass which rises like society’s id to devour them. The sequel has a bunch of kids on their way to a racing meet in the desert getting stuck in the middle of nowhere when their bus breaks down, inevitably getting picked off by a couple of savage killers – Pluto (Michael Berryman), who somehow survived having his throat torn out by a dog in the original film, and his uncle The Reaper (John Bloom), brother of Papa Jupe. The original’s parallels are lost, and to complicate what remains, somehow Ruby (Janus Blythe) has reformed her cannibal ways and is now married to Bobby (Robert Houston), who only appears at the start as his PTSD makes it impossible for him to return to the desert. Ruby is the one who knows what’s happening out there, but the heroine is Cass (Tamara Stafford), a plucky blind girl with a hint of psychic powers … nothing really gels as horny kids wander about in the night, not realizing until too late that something nasty wants to kill them. Arrow’s Limited Edition is an upgrade from Kino Lorber’s bare-bones release; the 2K transfer looks really good, there’s a commentary from The Hysteria Continues plus a half-hour retrospective in which actors Berryman and Blythe and producer Peter Locke are quite candid about the production’s problems. The Blu-ray comes in a sturdy slipcase with a booklet and a set of lobby cards.

Varda by Agnes (Agnes Varda, 2019)

In the final two decades of her life, Agnes Varda became her own subject. Her wonderful documentary The Gleaners and I (2000), in which she explored the lives of people on the fringes of society who live by gleaning value from what the rest of us discard as scraps, became a meditation on her own work and, more movingly, the process of growing old. The works which followed – The Gleaners and I: Two Years Later (2002), The Beaches of Agnes (2008), the television series Agnes Varda: From Here to There (2011), Faces Places (2017) – are introspective memoirs in which she explores her relationship to the world and how that relationship has shaped her work as a filmmaker. As an artist, Varda is able to articulate her intentions and process with a great deal of clarity. In her final film, Varda by Agnes, which premiered at the Berlin Film Festival six weeks before her death on March 29th, she had refined this self-assessment to a point where it had become a kind of performance – much of the film is woven together from a collection of different public appearances where her thoughts and observations flow effortlessly from one to the next, interspersed with clips from her movies and encounters with several people she had worked with over the years – actress Sandrine Bonnaire, cinematographer Nurith Aviv. Varda’s personal charm is in full force as she gives what amounts to a valedictory performance, leaving us with her own firm definition of the meaning of her work. Varda by Agnes is celebratory, with a touch of melancholy, a relaxed coda to a body of work which is rich with insight and innovation, spanning a remarkable six-and-a-half decades. The BFI’s dual-format edition includes an 83-minute talk she gave at the BFI Southbank in 2018, a 12-minute featurette in which Varda explains her attachment to Instagram, and a video essay on her work by film critic Amy Simmons.

Comments