Clearing the docket: Arrow Video

It’s a truism that a bargain is seldom a bargain; you’re likely to end up spending more when you see a “good deal” than if you hadn’t seen it. I don’t know if it’s because of the Covid lockdown, but there seem to have been a hell of a lot of sales over the summer … or maybe it’s just that I’ve been noticing them more because I’ve spent so much time online while hanging around my apartment. Either way, I’ve been spending stupid amounts of money ordering movies from various sites … and getting irritated because of postal delays on orders from the U.S. and U.K. due to the pandemic which sometimes means waiting a couple of months for something to arrive (and then wondering why the hell I ordered it when it does). Luckily there’s a great distributor named Unobstructed View operating in Canada now and their orders arrive fairly quickly … and that includes a lot of Arrow releases. (I just received a package of pre-orders and back-orders from them yesterday, including Criterion’s Bruce Lee set, Synapse’s 4K restoration of Jorge Grau’s Living Dead at Manchester Morgue – my favourite post-Dawn of the Dead Euro-zombie movie, Lucio Fulci notwithstanding – plus a movie I knew nothing about, Pete Schuermann’s The Creep Behind the Camera, and Arrow’s massive limited edition Gamera collection, which already went out-of-print pretty much on release day.)

*

Terraformars (Takashi Miike, 2016)

With over a hundred features in thirty years, it’s obvious that making films is at least as important to Takashi Miike as the films he makes. It’s a compulsion. At sixty, he shows little sign of slowing down as he turns out a dizzying mix of pulp entertainment and serious art. He can follow a masterpiece like Over Your Dead Body (2014), which both encapsulates and deconstructs a whole history of Japanese theatrical and cinematic costume tragedy, with the pulpy excesses of the manga adaptation As the Gods Will (also 2014). Terraformars was one of only two films he directed in 2016, so a slow year for him, and it’s one of his seemingly tossed off manga adaptations, heavy on the CGI. It starts with an obvious reference to Blade Runner, with a young couple running through narrow crowded streets pursued by heavily armed cops – there’s even a flying car which skirts copyright infringement in its resemblance to Blade Runner’s spinners.

The couple, wanted for murder, are offered an alternative to prison and/or execution: join a mission to Mars to exterminate the cockroaches which were imported hundreds if years earlier as part of a terraforming operation. The crew is made up of various outcasts, all working for a fashion-conscious Japanese businessman determined to claim the Red Planet for Japan. What they don’t know is that the bugs have mutated into hulking humanoid creatures determined to resist Earth’s imperial ambitions.

They also find out quite late that they’ve had their DNA mixed with that of various insects, giving each member of the team a different set of super powers. Not that that helps in the long run as almost everyone ends up dead after a series of futile battles. Terraformars is a kind of candy-coloured gloss on Starship Troopers, using less-pointed satirical jabs to paint an equally gloomy view of human arrogance and genocidal tendencies.

Arrow’s Blu-ray includes a feature-length making-of, a collection of actor interviews, some brief outtakes, and a booklet essay by Miike authority Tom Mes which argues that the movie is more serious than it first appears.

*

in Stanley H. Brasloff’s Toys Are Not For Children (1971)

Toys Are Not For Children (Stanley H. Brasloff, 1971)

Stanley H. Brasloff’s Toys Are Not For Children (1971) would make a suitable companion feature for Ted Post’s The Baby (1973); though it’s somewhat grungier and less polished, it has a similar queasy view of family dysfunction and perverse sexuality. Jamie Godard (Marcia Forbes) is arrested at an adolescent developmental stage, fixated on the father who abandoned her and her angry mother years ago. He still sends her toys on her birthday and she invests all her confused sexual longings in a large stuffed soldier doll (in the opening scene, her mother walks in on her masturbating with the doll while longingly calling for her father).

A queasy porn atmosphere hangs over the movie, yet it plays with that in order to explore Jamie’s issues from a psychological perspective rather than simply aiming for sleazy titillation. Jamie gets a job at a toy shop and ends up marrying her co-worker, Charlie (Harlan Cary Poe), who initially seems like a creep who harasses her at work, but turns out to be surprisingly accommodating when she refuses to have sex with him, preferring to sleep with her doll.

Having met a woman at the store who turns out to be Pearl Valdi (Evelyn Kingsley), a prostitute with a fairly laid-back attitude towards her work, Jamie is drawn to the game as a way of acting out her own frustrated fantasies – she takes older customers whom she calls “daddy”, indulging in a form of displaced incest. Through Pearl, who knows her father (an alcoholic who lives in a seedy hotel), Jamie at last gets to meet the man of her troubling dreams. He doesn’t recognize her and she gets to act out her long-held fantasy … which completely collapses when he realizes after the fact who she is and rejects her in horror.

The mix of psycho-sexual drama and queasy exploitation makes Toys a fascinating and frequently uncomfortable viewing experience. It would’ve been easy to dismiss if not for the generally fine performances – particularly Forbes, who invests Jamie with a genuinely disturbing childish sexuality, Fran Warren as her Margaret White-like angry mother, and especially Kingsley as Pearl, one of the most sympathetic prostitutes seen not only in exploitation but even in mainstream movies of the period, a smart woman well aware of who she is and what she’s doing.

There’s a commentary from Kat Ellinger and Heather Drain, an interview with Stephen Thrower about the career of Brasloff, and a video essay by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas about the relationship between dolls and female sexuality.

*

Crimson Peak (Guillermo del Toro, 2015)

This was an unnecessary purchase because although the Arrow contains a few more extras, the original Universal disk was perfectly fine. It would have made more sense to have bought the out-of-print Arrow limited edition when it was available, because that at least had deluxe packaging which included a book. That said, Crimson Peak (2015) is one of my favourite del Toro movies, a lush, creepy classical Gothic romance with an excellent cast and terrific production design. Of all his movies, this is the one which most successfully bridges the two very different strands in his work – the dark fantasies he makes in Spanish and the big budget English-language spectacles.

*

Hitch Hike to Hell (Irvin Berwick, 1977)

It would be hard to get further from the opulence of Crimson Peak than this bit of low-budget drive-in exploitation. Hitch Hike to Hell (1977 – for some reason IMDb says incorrectly that it was released in 1983) was the final feature of Irvin Berwick, a former child musical prodigy who had a long career as a dialogue director beginning in 1945 and became an occasional director in 1959 with The Monster of Piedras Blancas. (After Hitch Hike, he’s reputed to have made a number of porn films under pseudonyms.)

Bleak and quite nasty, Hitch Hike to Hell was shot in 16mm and blown up to 35mm, giving it a coarse, grainy look which is undeniably appropriate. There’s no mystery or suspense because the serial killer who rapes and kills runaway teenagers is the protagonist – we’re with him from the start and only escape his presence during the brief intervals with the police trying to track him down (led by familiar B-movie and television presence Russell Johnson). The script by John Buckley has some obvious echoes of Psycho – laundry delivery man Howard Martin (Robert Gribbin) has an unhealthy relationship with his overly clingy mother (Dorothy Bennett) and kills in part as a form of sexual release overtly connected to her – but it doesn’t waste time digging into the psychology of the pathetic killer. In traditional exploitation style, it presents itself as a kind of public service warning about the dangers of hitchhiking.

Only in the final stretch does it stir up dramatic tension as the police urgently search for an eleven-year-old girl who has taken off to go to her grandmother’s place in another town because she can’t stand hearing her parents’ endless arguments about money. In a mainstream movie there’d no doubt be a tense last-minute rescue … but not here. The tone becomes grimly nihilistic, providing no relief.

Gribbin gives a big, twitchy performance, transforming in a moment from a goofy, friendly guy to a bug-eyed maniac – all it takes is for a hitchhiker to say something disparaging about her (and at one point his) mother to plunge him into a fugue state. When he emerges, he doesn’t remember what he’s done, but as he sees reports on TV and in the paper, he starts to have flashbacks and begins to fall apart. His eruptions of horror at his own actions are the most effective moments in the movie.

Arrow offers a choice between an open-matte 1.33:1 image or one cropped to 1.85:1, both apparently from the same 2K restoration. There’s a lengthy interview with Stephen Thrower about Berwick’s career and the production of Hitch Hike, a video essay by Alexander Heller-Nicholas about the treatment of hitchhiking in the movies, and a long interview with musician and singer Nancy Adams who provided the catchy country-style theme song just a few years after contributing to the soundtrack of Disney’s Robin Hood.

*

Inferno of Torture (Teruo Ishii, 1969)

Although Teruo Ishii’s Inferno of Torture (1969) can be classed as exploitation, it’s in a much classier vein than Hitch Hike to Hell, its artistry making it much more unsettling. Another of Ishii’s films in the “erotic grotesque” genre (it was his fourth of seven films made in 1969, culminating in Horrors of Malformed Men), it once again uses the form of the Japanese costume drama to both exploit and comment on the historical inequalities, both economic and gendered, of Japanese society. A young woman who falls into debt is indentured as a geisha for two years as a way of repaying what she owes … but she quickly learns that she’s actually become enslaved as a prostitute to the holder of her debt. To increase the women’s value, they are subjected to extensive tattooing, which makes them more exotic to Westerners who have begun to establish a presence in the formerly insular nation. All of the unpleasantness – physical abuse, murder – is portrayed with paradoxical visual elegance, with lingering emphasis on the elaborate tattooing of captive female bodies.

Arrow’s disk has a bright and colourful image accompanied by a commentary from Japanese cinema expert Jasper Sharp, who is also present in a taped lecture about the erotic grotesque in Japanese culture recorded at the Miskatonic Institute.

*

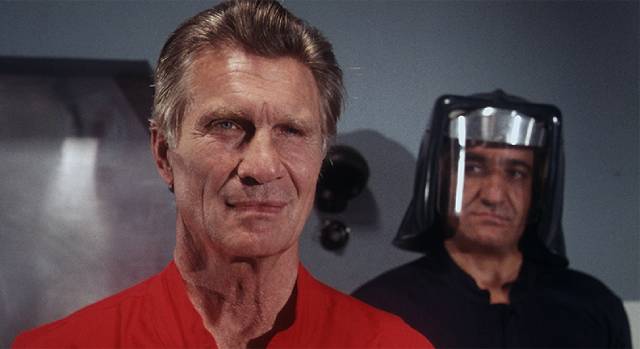

Horror Express (Eugenio Martin, 1972)

Franco’s Spain, while politically horrendous, was attractive to producers because it was relatively cheap to make movies there, with varied landscapes and plentiful material and human resources. Samuel Bronston made a series of sprawling epics there, from King of Kings in 1959 to Circus World in 1964; many spaghetti westerns were shot there (including Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy, A Fistful of Dynamite and parts of Once Upon a Time in the West). Foreign producers were welcomed because they brought money into the country; native filmmakers, on the other hand, had to contend with restrictive censorship under the regime. But occasionally foreign producers would work with Spanish directors, which was the case with Horror Express (1972), produced by the American Bernard Gordon, a writer who ironically was blacklisted in Hollywood in the ’50s, and directed by Spaniard Eugenio Martin.

The film’s international cast was headlined by Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing (who famously tried to back out because of his wife’s recent death and was persuaded by his friend Lee to throw himself back into work as a way of dealing with his grief), with Telly Savalas turning up in the third act and chewing every piece of scenery in sight – the contrast between the disciplined and understated Brits and the larger-than-life American is just one of the movie’s amusing aspects. The rest of the cast is filled out with Spanish actors.

A rousing piece of pulp entertainment, Horror Express weaves elements of The Thing and Murder on the Orient Express together in a fast-paced monster narrative. Chilly Sir Alexander Saxton (Lee) has discovered a prehistoric man frozen in a Siberian cave and is trying to sneak his prize back to England on the Trans-Siberian express in 1906. His friendly rival in science Dr. Wells (Cushing) is curious about what’s in the crate, particularly when odd sounds can be heard inside. The caveman himself might have been dead and frozen for tens of thousands of years, but there’s an alien force trapped in the body which is much older (seems it’s been on Earth since the time of the dinosaurs) and now it escapes and moves from person to person, sucking out knowledge and life force as it gains strength. While Saxton and Wells try to figure out who the alien is possessing, Cossack Captain Kazan (Savalas) storms aboard the train and starts kicking butt to find out who’s killing the passengers.

I’ve always liked movies set on trains – partly because I loved riding in trains as a little kid, partly because as a setting they combine claustrophobic confinement with ceaseless motion – and Horror Express satisfies my craving for both trains and hostile aliens. Martin keeps things moving, the cast give it their all (Cushing invests Wells with an air of amused curiosity about the goings-on, all the more poignant when you know what he was going through personally at the time).

Arrow improves on the old Severin Blu-ray’s image while carrying over most of that edition’s extras (only Peter Cushing’s audio interview is missing), while adding a new commentary from Stephen Jones and Kim Newman, plus a couple of interviews about the film and producer Gordon.

*

White Fire (Jean-Marie Pallardy, 1984)

There’s not much to say about this ’80s oddity. White Fire (1984) is an attempt by a French exploitation director, who was mostly known for softcore porn, to do a big international action thriller. It starts with a family attempting to escape from a repressive police state (maybe in Eastern Europe). The mother and father are killed, but the two children are rescued by a man who raises them. Given this rough start in life, it’s not surprising that the kids grow up close – very close. As adults who have become thieves, they have a really incestuous attachment to one another.

Ingrid (Belinda Mayne) has a job at a huge diamond mine in Turkey, while Bo (Robert Ginty, fresh off Exterminator 2) works on the outside with a fence who handles what they steal. After blasting causes a landslide which exposes a cave entrance, one of the mine’s workers discovers the legendary White Fire, the world’s largest diamond. There is a problem, however: it’s highly radioactive and anyone who touches it is instantly burned to death (standing right next to it doesn’t seem to be a problem, though). Various factions try to get their hands on it; there are car chases and murders … but the plot remains hazy and the action is clumsily staged.

The movie gets weird – and this is what has gained it a kind of cult status – when Ingrid is murdered and Bo discovers a woman who looks just like her. Olga (Mayne again) is on the run from some criminals and agrees to help Bo by taking Ingrid’s place in the scheme to get the big crystal. This entails a brief stay in a kind of lesbian commune where she has some plastic surgery to cement the resemblance. The ruse doesn’t fool Noah Barclay (Fred Williamson), the henchman sent to track down Olga. He also gets mixed up in the quest for the rock … as does the mine’s ruthless head of security, Olaf (former sword-and-sandal and spaghetti western star Gordon Mitchell).

The action plot is mostly strung together without much interest in coherence, but that becomes secondary when Bo falls for Olga – who, remember, looks exactly like his sister Ingrid – and they embark on a sexual relationship, which for him amounts to finally consummating his incestuous desire. It’s a peculiar tangent for a mainstream thriller which reflects back on Pallardy’s porn origins, as does the fact that Mayne spends a fair amount of time naked.

Arrow’s Blu-ray has been mastered from a less than pristine source, but the image probably doesn’t look much different from what it was like in the movie’s theatrical run. There’s a commentary from the now seemingly ubiquitous Kat Ellinger, plus interviews with Pallardy, editor Bruno Zincone and co-star Williamson.

*

The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995)

I was recently reminded of Abel Ferrara’s vampire movie when writing about Larry Fessenden’s Habit (1995) and decided to take another look. I don’t think I’d seen it since its original theatrical run, but it turned out to be very much like my memory of it, so it had obviously made an impression on me. Its two most distinctive characteristics are the black-and-white photography of Ken Kelsch and the highly verbal screenplay by Nicholas St. John (both frequent Ferrara collaborators). The latter is justified by the film’s setting amongst graduate students in philosophy at NYU; the characters talk endlessly about moral issues and the meaning of life. Because this milieu and these kinds of conversations are rare in American film, it’s difficult at times not to see The Addiction as pretentious and parodic. It’s like sitting in a college common room listening to a bunch of students who’ve just discovered Nietzsche and Schopenhauer for the first time.

When Kathleen Conklin (Lili Taylor) is bitten by a vampire one evening in a back alley, she’s suddenly forced to contend with her own physical reality after living for years in her own head. Subjected to compulsions she can’t control, she gains a new understanding – visceral rather than intellectual – of all the philosophy she’s been imbibing for years. Evil has manifest as a vital reality rather than a word game. Although she initially fights against her new nature, she eventually embraces it, leading to the film’s comic-horrific climactic set-piece as she delivers a speech at the party to celebrate receiving her doctorate before unleashing her vampire friends on all the stuffy academics from the philosophy department.

The black-and-white imagery gives the film an air of cool detachment which extends to Taylor’s performance. Even before she’s bitten and distanced from the everyday world of New York, she seems closed up inside herself. But while becoming a vampire initially seems liberating, she ultimately has to confront the horror of her own actions (recalling and refuting her coolly intellectual response to watching footage of the My Lai massacre in her class during the opening scene). This is where St. John and Ferrara abruptly depart from vampire tradition; feeling guilt, she accepts the Host and absolution from a Catholic priest and expels the vampire within herself. This coda is a reminder of the Catholicism which underlies a lot of Ferrara’s work, and the struggle so many of his characters wage with sin and guilt.

Arrow’s Blu-ray presents an excellent 4K restoration of the film, accompanied by a commentary with Ferrara in conversation with critic Brad Stevens, plus a number of featurettes. There’s a new retrospective documentary by Ferrara which gives members of the cast and crew a chance to reminisce about the production, interviews with Ferrara and Stevens, and an archival piece about editing the film.

*

The Beast Within (Philippe Mora, 1981)

I actually enjoyed Philippe Mora’s The Beast Within (1981) more watching it on disk than I did seeing it in the theatre almost forty years ago. Back then, it seemed pretty dumb – it is, after all, about a were-cicada – but it doesn’t mock its own ridiculousness, playing everything grimly straight. That alone now seems refreshing after so much irony and pastiche has been unloaded on the genre.

Echoing Hammer’s Curse of the Werewolf, the film begins with a woman being raped by a degenerate man. Stranded on a lonely road at night by a broken down car, she’s waiting for her husband to return with help when a barely seen figure drags her into the bushes and assaults her. The result is a son whom her husband accepts despite his origins. Seventeen years later, that son, Michael (Paul Clemens), is suddenly changing from a normal all-American teenager into something else. Doctors aren’t sure what’s happening, but it appears that some genetic anomaly is beginning to manifest itself.

Dad Eli (Ronny Cox) and Mom Caroline (Bibi Besch) reluctantly face the thing they’ve kept suppressed for years and head back to the small town where the rape occurred to try to find out whatever they can about Michael’s biological father. They’re met with suspicion, the locals reluctant to talk about the deformed madman who had escaped from a basement prison and was killed after committing the rape. But gradually the story is pieced together while Michael’s condition grows worse. Being a mutant cicada, now aged seventeen, his true nature is emerging and the giant insect goes on a rampage.

Philippe Mora is a hard figure to pin down. I first encountered his work when I saw Mad Dog Morgan in the mid-’70s. A film that deserves to be better known, it provided Dennis Hopper with one of his best roles and stands as a significant work from the first wave of the New Australian Cinema. But before that he’d caused some controversy with his documentary Swastika (1973), which portrayed the twelve year reign of the Third Reich through newsreels and propaganda films produced by the Nazis themselves, and for the first time showed Eva Braun’s home movies of Hitler. That was too much for some critics who felt that it was dangerous to humanize the Fuhrer and see the regime as it saw itself.

It was this strong background which triggered my initial negative response to The Beast Within, which was Mora’s first film since Mad Dog Morgan. In moving to the States, he had apparently sold out. His subsequent career has been quite prolific and I confess I haven’t seen much of his work other than a few exploitation movies like Howling II, Howling III and Communion – all quirky and idiosyncratic, but hardly substantial contributions to Cinema.

But again, I quite enjoyed seeing The Beast Within again on Arrow’s Blu-ray; it’s a sturdy if unexceptional exercise in genre filmmaking which retains the darker tone of horror from the ’70s. The cast treat the material seriously and Tom Holland’s script (from a novel by Edward Levy) manages to hit most of the marks necessary to satisfy genre expectations. Also pleasing is the supporting cast which includes L.Q. Jones, R.G. Armstrong, Logan Ramsey, Don Gordon and Luke Askew.

The disk includes a commentary with Mora in conversation with Calum Waddell, a lengthy retrospective documentary, and a featurette on Mora’s storyboarding process.

*

Def-Con 4 (Paul Donovan, 1985)

In the wake of Mad Max’s international success, post-apocalyptic hellscapes became the setting of choice for action B-movies. While a lot of these emerged from Italy, which was the epicentre for imitative exploitation, these movies popped up in many places. Even Canada, whose industry at the time was still constrained by the tax shelter rules which too often facilitated American control rather than fostering a genuine national cinema (as the British quota system had often held back filmmakers in the UK in the ’30s by forcing them to make quick, cheap imitations of Hollywood movies). But despite those limitations, interesting and entertaining movies did appear, one of them being Paul Donovan’s made-in-Nova Scotia Def-Con 4 (1985).

To be honest, I’m not sure exactly what Donovan’s version was like, because distributor New World Pictures did a bunch of post-production work, with additional shooting and editing (hence IMDb’s listing of Tony Randel as an uncredited co-director). Whatever the facts, Def-Con 4 is an effective low-budget movie about the end of the world. It begins on an orbiting missile platform as the bored crew monitor the deteriorating political situation down below, debating whether or not to unleash their weapons when things go from bad to worse… Should they ensure the complete obliteration of the planet or leave the few survivors of the ground-based war to sort things out?

A remote signal from below triggers a re-entry sequence and after a fight in the control room, the missiles are jettisoned into space … all except one, that is, which malfunctions. The satellite crashes and cannibals immediately take one crew member; the others set out to find what remains of civilization, discovering instead warring tribes and mutants. Captured and imprisoned, they realize the danger of a petty warlord getting hold of that one remaining missile and have to fight to escape. By the time the messy rebellion has ended with a lot of people dead, our hero has reached the same nihilistic point as Taylor at the end of Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970), where it’s obvious that it’s not worth saving humanity.

While it’s little more than a footnote in the post-apocalypse genre, Def-Con 4 does have some imaginative touches and there’s character actor Maury Chaykin making the most of his role as a rather unwholesome survivor. The effects aren’t bad for the budget either. It doesn’t seem to rate very highly with reviewers on the Internet, so maybe my opinion is touched with a trace of residual patriotism. That may also explain my vague irritation with Arrow’s U.S.-centric disk. They might at least have called on Canuxploitation’s Paul Corupe to contribute a commentary, maybe with Donovan, who still seems to be around … but what we get instead is Chris Poggiali talking about New World Pictures, Christopher Young talking about his score, and Michael Spence talking about working for Roger Corman as an editor. Def-Con 4 itself is barely an afterthought in all the interviews.

*

Sister Streetfighter Collection

(Kazuhiko Yamaguchi & Shigehiro Ozawa, 1974-76)

The main point of interest in this series of martial arts thrillers from Toei is that they centre on a fearless young woman, based in Hong Kong, who travels to various places in Japan to find missing friends and relatives who have become caught up in criminal conspiracies, kicking a lot of ass along the way. A spin-off from Sonny Chiba’s Streetfighter series, these movies star Etsuko Shihomi, who was still a teenager at the time. The plots are fairly basic and generic (the Japanese industry was pumping this stuff out by the truckload at the time), but the action scenes are quite well-handled and, as always, it’s enjoyable to see a woman get the best of hordes of arrogant men.

All four transfers in Arrow’s two-disk set are clean and detailed. There’s an alternate censored U.S. cut of the first film and three brief interviews – with Sonny Chiba, director Kazuhiko Yamaguchi, and screenwriter Masahiro Kakefuda, who co-wrote three of the movies.

*

The Annihilators (Charles E. Sellier Jr., 1985)

Vigilantes have long been popular in the movies, though in more recent years filmmakers have tried to problematize them – Neil Jordan’s The Brave One, James Wan’s Death Sentence (both 2007), Daniel Barber’s Harry Brown (2009) – by tut-tutting and making sure the audience knows people really shouldn’t be doing this kind of thing. The problem with that is that it takes the primal pleasure out of revenge. I hasten to add that I mean this purely from a storytelling point of view; real life is a whole other issue, with self-appointed assholes like George Zimmerman doing horrific things (with deranged and twisted laws in some places letting such monsters get away with their crimes). In a movie, deliberately constructed to clarify who’s good and who’s bad, audiences can indulge their baser instincts guilt-free by rooting for characters pushed beyond endurance who take on irredeemably bad actors and put a stop to their predatory ways.

Although it’s a bit more complicated than the movies it inspired (and its own sequels), Michael Winner’s Death Wish (1974) set the standard. By the early ’80s, William Lustig could release a movie baldly titled Vigilante (1982) and the working class hero and his friends could be cheered on as they mop up the scum who are ruining their neighbourhood. Charles E. Sellier Jr. followed that formula to a T in The Annihilators (1985), the story of a group of Vietnam vets who reconnect when vicious thugs kill one of their friends. That early scene is pretty nasty, what with the friend being a paraplegic in a wheelchair who runs a small neighbourhood store. When the gang show up looking for protection money, they start molesting a female customer and things quickly get out of hand, leaving both the vet and the woman dead.

Arriving for the funeral, Bill (Christopher Stone) finds a community living in fear of drug-dealing gangs. He calls in his buddies and tries to organize the locals into a kind of mutual defence society, but regular people don’t necessarily have the stuff to put their own lives on the line … in fact some of them are dead set against using the vets for protection and feel safer just putting up with the abuse. It gets messy and things escalate, with the police more concerned about putting a lid on the potential rise of vigilantism than on reining in the criminal gangs.

Needless to say, it all ends up with a pitched battle in the streets and the oppressed finally find the spine to take on the gangs. In a final twist, the federal agent who has been dogging the vets turns out to have been on their side all along, diverting the local police to give the vigilantes room to operate.

The Annihilators has that gritty ’80s exploitation vibe and Sellier keeps things moving with well-staged action sequences. It’s not surprising that the man behind the notorious Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984), of Santa-with-an-axe fame, isn’t too concerned with moral niceties. At least, I wasn’t surprised until I watched an interview on the disk with filmmaker David O’Malley who sketches in Sellier’s early career as a writer and producer of “documentaries” about Biblical and occult subjects – In Search of Noah’s Ark (1976), In Search of the Historic Jesus (1979) – not to mention various family-friendly Grizzly Adams movies and TV series, none of which seem consistent with his two violent exploitation movies.

Arrow have given the film a 2K restoration from a 35mm interpositive and the image is surprisingly good. In addition to the O’Malley interview, there’s another with co-star Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs which conveys some of the flavour of making this kind of movie back when things weren’t quite so tightly regulated.

Comments