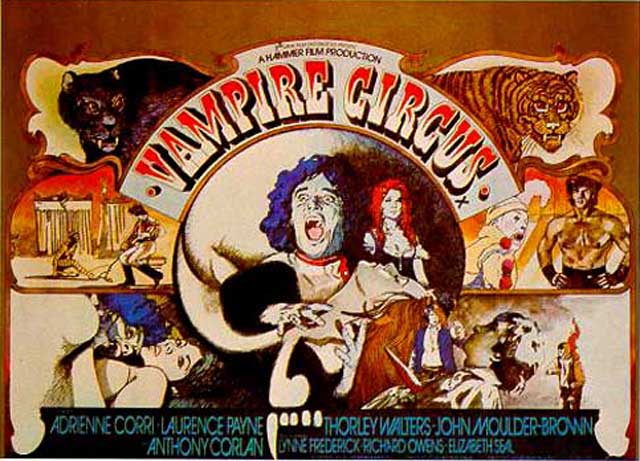

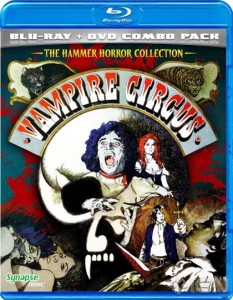

DVD of the Week: Vampire Circus (1972)

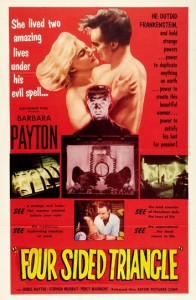

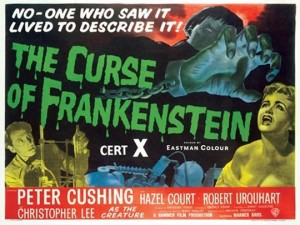

Although Britain’s Hammer Films was first formed in the 1930s, initially in an attempt to expand a theatre chain into areas of production and distribution, only five films were made before the war – comedies and mysteries. Production resumed after the war with more comedies, mysteries and thrillers. It was 1953 before the company took its first tentative steps into the genres it’s now best known for – horror and, to a lesser degree, science fiction – with two films by Terence Fisher, Spaceways and Four-Sided Triangle; and 1955 before there was a clear indication of how the company could carve out a distinctive identity for itself, with Val Guest‘s adaptation of Nigel Kneale’s BBC serial The Quatermass Xperiment. In the next couple of years, Hammer slowly built on this start with several more blends of science fiction and horror – the Quatermass imitation X the Unknown (Leslie Norman, 1956), The Abominable Snowman and Quatermass II (both Val Guest, 1957) and finally the key movie which was to define Hammer for the remaining twenty years of its existence: Terence Fisher’s garishly colourful The Curse of Frankenstein.

If you look back over Hammer’s post-Frankenstein output, it’s surprising to see that the famous Gothic horror movies constitute only about 40% of the company’s productions. The rest were various comedies, costume adventures, contemporary psycho-horror thrillers, and occasional SF, war films and mysteries.

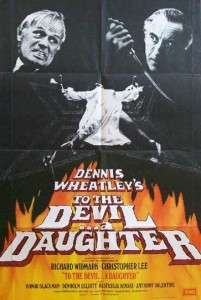

But while the company maintained an average output of around ten features per year, by the end of the ’60s Hammer Films was in serious decline. While their late ’50s horror productions had seemed shocking – lush colour, fairly graphic (for the time) gore and violence – a decade later the times had pretty much passed them by. Sex and violence had become more explicit and more common in the mainstream, and Hammer’s Gothic horrors began to look quaint and old-fashioned. The company tried to move with the evolving tastes of the audience, but adding more blood and throwing in a lot of nudity came across as what it really was: not a new freedom, but a kind of last-gasp desperation. In the final years before production ceased in 1976 (with To the Devil … A Daughter, an attempt to recapture the success of Terence Fisher’s Dennis Wheatley adaptation, The Devil Rides Out: but while Peter Sykes’ movie actually isn’t as bad as its reputation, it is done in by a very weak ending), the company made several attempts to change its formula, hoping to recapture the audience which no longer seemed to care.

By 1972, Hammer was releasing things like Demons of the Mind (also by Peter Sykes), a silly Freud-infused period piece about a twisted bourgeois family in which the father’s sexual hangups have corrupted his son and daughter, who have a decidedly incestuous relationship which somehow results in a series of murders in the neighbourhood. That year also saw Hammer’s penultimate abuse of Bram Stoker’s famous vampire, Dracula A.D. 1972 (Alan Gibson), which revived poor Christopher Lee in modern London where he appears to be so intimidated by the go-go lifestyle (as Lee M. Kaplan pointed out in his Cinefantastique review) that he keeps himself hidden in a ruined church for the entire duration of the movie. And then there were two failed psycho-horror efforts, Fear In the Night and Straight On Till Morning … and the next year, no horror at all.

1974 saw the last gasps of Hammer’s dynamic duo, with The Satanic Rites of Dracula (Alan Gibson again) and Terence Fisher’s dreary swansong, Frankenstein and the Monster From Hell, as well as Roy Ward Baker‘s The Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires (a co-production with Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers, which is exotically novel if nothing else), and perhaps the company’s most successful attempt to rethink its Gothic heritage, Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter (dir. Brian Clemens). Here the vampire sucks out the life force rather than the blood of its victims, and opposed to the monster is a swashbuckling, sword-wielding action hero rather than a stake-packing doctor. It was apparent that the company hoped to launch a new series with this character, but no sequel ever appeared.

Less rousingly entertaining, but certainly more distinctive, was 1972’s oddest release: Robert Young‘s Vampire Circus. Until the release of this strange film, Hammer’s vampire revisionism had been largely limited to an ever-increasing display of large-breasted starlets. But here was something different both in style and tone, an attempt to blend Hammer’s familiar Gothic landscape (a small, plague-ridden European town somewhere in the 19th Century) with a low-budget Fellini-esque carnival atmosphere and some genuinely perverse undercurrents.

In Vampire Circus, the small town of Schtettel is cut off by its neighbours because of a mysterious plague which the local doctor claims is natural, but everyone else believes to be the result of a curse placed on the community fifteen years earlier when a torch-bearing mob killed the local nobleman/vampire Count Mitterhouse. But despite the fact that anyone trying to get out is shot at by the neighbours, one day a colourful gypsy circus rolls into town and, like the travelling show in George Pal’s The Seven Faces of Dr. Lao (1964), begins to work on the desires of the town’s inhabitants, particularly awakening the sexuality of the young. The nightly performances offer acrobats turning into real bats, big cats transformed into seductive performers – one of the film’s highlights is a highly eroticized dance by the virtually naked tiger-woman – and a hall of mirrors which shows townspeople their own deaths. Turns out that the circus has come to town to revive the un-dead Count, and in order to do it, they have to drain the blood of all the children of the men who killed the vampire.

Although Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula had the vampire Lucy preying on young children (and notably introduces the vampire theme with the Count tossing a baby in a sack to his hungry brides to get them away from the imprisoned Harker), the focus on killing children was not a standard element of vampire movies.

Looked at today, the lengthy prologue sequence seems quite radically daring and it’s surprising that the filmmakers got away with it. A woman lures a young girl from an idyllic woodland clearing through the gates of the local castle, home of Count Mitterhouse, whom everyone in the neighbourhood knows is at least a murderer, responsible for the disappearance of a number of local children – but whom everyone is afraid to confront because, well, he’s the local nobleman and would just set the law on them if they cause him trouble. Inside the opulent castle, the woman (the local teacher’s wife, now the Count’s lover) hands over the young girl; the Count bites the child’s neck and drains her blood, leaving her lying dead on the floor as he and his mistress throw themselves into some energetic sex. As the Count says, “One lust feeds the other.”

While Hammer had gone all out with sex in the Karnstein trilogy (The Vampire Lovers [Roy Ward Baker, 1970], Lust For a Vampire [Jimmy Sangster, 1971], Twins of Evil [John Hough, 1971]) and Countess Dracula (Peter Sasdy, 1971), this was something quite different – not merely T&A, but a genuinely perverse eroticism. Combined with the carnival atmosphere, this promised a new direction for Hammer, perhaps something of a more European flavour than the mixture of staid English conventions and schoolboy titillation, a hint of the sensibility which would produce Alejandro Jodorowsky‘s perverse masterpiece Santa Sangre in 1989. The sexuality and the nightly performances with their transformations of animal to human and back again, give the film a dreamlike, almost magic realist tone, which makes it unlike any other movie produced by the company.

Unfortunately, the rest of Vampire Circus doesn’t quite manage to sustain the promise of the prologue. There seem to be a number of reasons for this, not least Hammer’s rigid budget-consciousness. Apparently Young needed two or three extra days to shoot bits and pieces of connective material, inserts and so on, but the front office said absolutely not, and told him to do whatever he could with what had already been shot. As a result, the film is short and quite choppy, awkwardly paced, with some details seemingly missing while other parts feel padded just to get the running time up to an acceptable 87 minutes.

There are also some weak performances. Robert Tayman as Count Mitterhouse isn’t very menacing and wouldn’t look out of place among the trendy moderns of Dracula A.D. 1972, and John Moulder-Brown makes for a very vapid young hero, thrown in to attract the “youth audience”. The vampires’ fang-baring is often exaggerated and almost parodic, and Young’s camerawork less inventive than the underlying concept.

But despite these weaknesses, Vampire Circus is a strange and distinctive piece of work and, given its anomalous place in Hammer’s output, it’s perhaps fitting that having been overlooked for DVD release, this edition from Synapse Films is the very first Hammer film to turn up on Blu-Ray. It’s a nicely packaged edition (including a DVD version), with a few interesting if not terribly substantial extras. As it appears that Robert Young is still alive, it’s a pity he wasn’t brought in to record a commentary track which might have provided some insight into the thinking behind this attempt to step out of the Hammer rut just before the company wasted away.

Comments

Hi Roger, another great article. I love Hammer studios and received today – an (expensive copy!) of the Authorized History of Hammer book Hearn & Barnes. Fantastic!