Recent Kino Lorber releases

Thanks to Kino Lorber, I’ve recently been able to revisit some movies I haven’t seen in forty or fifty years. I have vivid but fragmentary memories of these movies, and given how flawed memory tends to be, these recollections might very well be inaccurate or at the least distorted. The fact that these movies are now turning up on Blu-ray is both surprising and gratifying – several of them are made-for-TV movies-of-the-week, a genre which in conception was probably more disposable than the lowliest studio B-movie, essentially produced to fill air time between commercials. And one of these is something I’ve wanted to see again for five decades, though there’s always that reservation, the fear that it just can’t live up to my memories.

Fear No Evil/Ritual of Evil (Paul Wendkos/Robert Day, 1969/70)

I’m happy to report that it does, in fact, live up to what proved to be a rather general impression on which hangs one specific vivid detail. The general impression was of a really creepy atmosphere; the detail, an antique mirror which traps someone on an alternate, hellish plane. Perhaps it’s not surprising that this movie left a lasting impression as it was directed by Paul Wendkos, who had a knack for far more stylish visuals than most of the people working in TV production back then – his often extreme camera angles and distorting lenses flirted with excess which could easily have plunged into parody and camp, but his control of narrative kept things in balance, generating a powerful air of paranoid suspense.

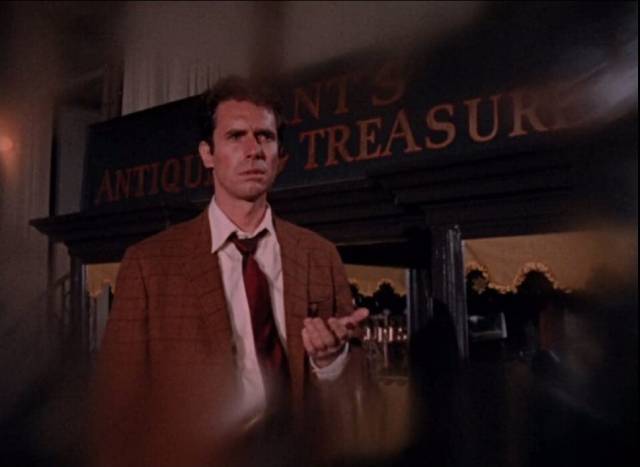

In Fear No Evil (1969), as in The Brotherhood of the Bell (1970), style is a major part of the substance, disorienting the audience to reflect the mental state of the characters. A man flees a building in panic as if pursued by an invisible threat. He’s a physicist named Paul Varney (Bradford Dillman). It’s midnight and he stops at an antique store, hammering at the door until the irritated owner finally opens up. He searches the store until he comes to a full-length antique mirror, which he buys with cash. The next day, when it’s delivered to his apartment, he has no memory of buying it. His fiance Barbara (Lynda Day), finding it ugly, doesn’t understand any more than him why he would’ve bought it.

Then he dies in an accident and his mother (Marsha Hunt), who has always disliked Barbara, invites her to stay at the family mansion so they can grieve together. Barbara discovers that the mirror has been moved into her room and at night she has vivid dreams – or are they visions? – of Paul beckoning her to join him on the other side, where instead of the bedroom she can see a long corridor with stone arches disappearing into the distance.

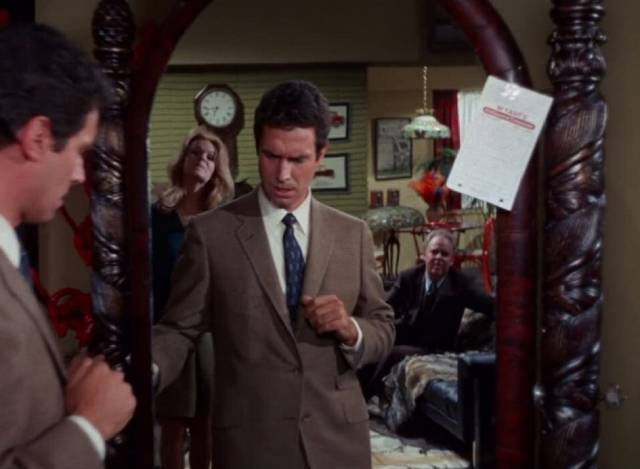

Just before the fatal accident, Barbara and Paul had met psychologist Dr. David Sorell (Louis Jourdan) and she consults him about her “dreams”. He’s a rationalist, but remains open to occult ideas as expressions of psychological states. Sensing the danger of Barbara becoming lost because of her inability to let go of Paul, he begins to investigate the mirror and the events leading up to Paul acquiring it. This takes him to an institute of occult studies run by a frosty woman named Ingrid Dorne (Katherine Woodville), who is very unhelpful. But he manages to steal a tape with Paul’s name written on the box; the recording is of an occult ceremony involving human sacrifice in an attempt to summon a demon.

Paul, it turns out, was to be a vessel for manifesting the demon and it’s not him but the demon beckoning Barbara into the mirror. Sorell races against time to save her from a terrible fate while also putting a stop to the plans of the Satanists at the institute.

Not a particularly original story, perhaps, but as so often its value lies in the telling. Richard Alan Simmons’ script is tightly constructed, providing a progressive series of reveals which add layers to the narrative, lending a sense of urgency which Wendkos’ builds on with his disorienting visual style. The cast – which also includes Carroll O’Connor as Paul’s boss and Wilfred Hyde-White as Sorell’s friend Harry Snowden, there to bounce ideas off and provide some occult exposition – plays it all with conviction. In other words, the movie transcends its basic function as programme filler and stands as a fine piece of ’60s horror filmmaking, fully living up to my fifty-two-year-old memory of the one time I saw it on a small black-and-white television set.

I have no memory of seeing the sequel made two years later. This turns out not to be surprising. Ritual of Evil (1970), written by Robert Presnell Jr and directed by Robert Day, manages to miss everything that worked so well in the first movie. The script is clumsy and repetitive, a series of episodes filling time between commercials without doing much to advance the narrative, while Day’s direction is perfunctory and unimaginative; he just moves the actors around and gets things done as quickly as possible without adding any flourishes to spice up Sorell’s investigation of the death of one of his patients, which may or may not have been suicide.

Once again there are Satanists, this time hanging around a prime-time soap opera beachfront property where Anne Baxter drinks away her days. It’s a bit like Dynasty with human sacrifice. Dull, unfocused and open-ended, it feels more like a miscalculated series pilot than an actual movie (in fact there were apparently plans for a series about Sorell, but they never materialized, perhaps because this was a dud). While writer Presnell had a long career in episodic television, perhaps explaining the lack of imagination, Day had some interesting work in his resume, going back to his days at Ealing Studios and his low-budget horrors for producer Richard Gordon in the ’50s (the latter collected in Criterion’s Monsters and Madmen box set from 2006). He made Hammer’s enjoyable She (1965) and did a lot of TV work in the ’60s on shows like Danger Man and The Avengers, eventually moving to the States for more TV work.

Was his talent blunted by the routines of U.S. network TV production? or was he just uninspired by Presnell’s mediocre script? Who knows, but while Wendkos’ Fear No Evil spawned an entire industry of supernatural movies-of-the-week and was capable of creating memories which have lasted half a century, Day’s Ritual of Evil is so forgettable that I can barely recall any details mere days after watching it on Kino’s double-feature Blu-ray.

*

Killdozer (Jerry London, 1974)

To my surprise, another MOW just released by Kino turns out to be better than I remembered. Jerry London’s Killdozer (1974) seemed pretty dumb to me when I saw it back in the mid-’70s, but now plays as a nifty variation on the killer machines trope best exemplified by Stephen King’s 1973 short story “Trucks”, which King himself adapted and directed in 1986 as Maximum Overdrive. Based on a Theodore Sturgeon story, Killdozer is an efficient little thriller with a cast of six, a setting limited to a single location (a California beach standing in for a small island in the Indian Ocean), and a menace given a perfunctory explanation which is all you really need.

An oil company exploratory team is working on a deadline to build an airstrip on the small island. There are tensions because some of the team dislike the guy in charge, Lloyd Kelly (Clint Walker), an ex-alcoholic who pushes them hard because he needs to prove to his bosses that he’s up to the task. One day, McCarthy (Robert Urich) is clearing a stretch of beach with the massive bulldozer when he runs into a strange metallic rock. What he and Kelly don’t know (but which we saw in the prologue) is that this landed from space sometime in the distant past. When Kelly takes over the ’dozer to shift the rock, a strange blue glow moves from the rock to the blade, in the process giving McCarthy severe radiation burns.

McCarthy dies and the ’dozer begins to act up; initially, the controls become unresponsive to the driver, but before long it’s driving itself, trashing the base camp and chasing the men down. One by one they die. It takes a while for the survivors to accept that the machine is now sentient and extremely malevolent, but even when they do, their plans to deal with it are pretty ineffectual and in the end only two survive after finally “killing” the killdozer.

Killdozer is more efficient than inspired; it’s fairly typical of ’70s made-for-TV horror, taking its concept as seriously as it needs to to keep viewers watching and reasonably entertained. Its inspiration was no doubt Steven Spielberg’s Duel (1971), but its ambitions are more modest – the man vs machine narrative doesn’t aspire to the existential dread of the earlier film, but remains at the most basic monster-movie level. But on that level, it does a very effective job and it engaged me for its brief 74-minute running time.

All three movies are given full-frame transfers on Kino’s disks, just as they would have been seen when originally broadcast on network TV, but all of them were shot with potential foreign theatrical sales in mind, so they play very well zoomed in to 1.78:1 on a modern television, giving each of them a more pleasing movie-like feel without so much dead space at the top and bottom of the frame. Each gets an audio commentary, and there’s an additional audio interview with Jerry London on the Killdozer disk.

*

Curse of the Undead (Edward Dein, 1959)

Although not made for television, I did see Edward Dein’s Curse of the Undead (1959) on TV sometime back in the ’60s or early ’70s and remember enjoying it at the time. This too stands the test of the time, its Southwest Spanish flavour making it reminiscent of the atmospheric Gothic horrors being made in Mexico around the same time by Chano Urueta, Fernando Mendez, Rafael Baladon and others[1]. That in itself would have made it memorable to me back then, but perhaps more importantly it may have been the first time I saw a movie which does something I’ve long appreciated: it blends two genres which are usually quite separate – horror and the western.

Edward Dein was a minor figure, a prolific writer of B-movies in the ’40s who turned to directing in the ’50s. He made only eight features between 1952 and 1966, with additional television credits up to 1978 (when he would have been seventy). Of the three features I’ve seen, The Leech Woman (1960) is dull generic horror; Shack Out on 101 (1955) is a real gem, transforming Red Scare espionage into virtual farce, made with real panache and featuring an excellent cast; and Curse of the Undead handles its mix of elements with seemingly effortless skill.

A small town is beset by a mysterious illness which is claiming the lives of girls and young women. At the same time Dr. Carter (John Hoyt) and his children Dolores (Kathleen Crowley) and Tim (Jimmy Murphy) and being harassed by rancher Buffer (Bruce Gordon), who wants to drive them off their land to expand his range. Doc Carter is baffled by the mysterious illness, though the audience is let in on the secret quite early – each person who succumbs has two small puncture wounds on their neck. After yet another patient dies, and coinciding with a violent confrontation between Tim and Buffer, Doc shows up dead.

Dolores believes Buffer is responsible and she’s determined to get justice even if the sheriff (Edward Binns) is reluctant to do anything against the most powerful man in the area. So she posts a reward for the death of those responsible for her father’s murder. A dark stranger dressed all in black shows up, a gunslinger named Drake Robey (Michael Pate), who accepts the job, though the sheriff warns him away. Robey, who has a condition which makes his eyes overly sensitive to sunlight, is mostly seen at night … and he obviously finds Dolores attractive, which raises the suspicions of Preacher Dan (Eric Fleming), who plans to marry her himself.

Papers found among Doc Carter’s effects illuminate the history of the town and prove that part of Buffer’s ranch actually belongs to the Carters because it was bestowed on the previous owners by the King of Spain. Those owners were the Robles family, which seems to have died out under a curse after one son, Drago, murdered his brother for taking his fiancee. Because of his crime, Drago became a vampire after he died and went out into the world as a killer for hire; now he’s back and he wants Dolores for his bride.

Needless, to say, when Preacher Dan relates all this to Dolores, she finds it hard to believe, attributing it to jealousy. The two threads – the land claim dispute and the vampire – are neatly woven together in the script by Dein and his wife Mildred, making for a satisfying piece of genre storytelling. It’s all very nicely shot by Ellis Carter, among whose many credits are ’50s favourites The Incredible Shrinking Man and The Monolith Monsters (both 1957).

Like Fear No Evil, Curse of the Undead doesn’t betray my memory of a single television viewing five decades ago.

*

in Lamont Johnson’s The Groundstar Conspiracy (1972)

The Groundstar Conspiracy (Lamont Johnson, 1972)

Memory is also not betrayed by yet another recent Kino release, but in a less satisfying way. Lamont Johnson’s The Groundstar Conspiracy (1972) is a frustrating espionage movie based on a novel by British pulp sci-fi author L.P. Davies. The first thing that bugged me back in the day was that the sci-fi element was stripped away completely. (The book was called The Alien.) Knowing that now, I’m able to watch it more on its own terms, but it still has issues, not least in its seeming validation of a fascist protagonist.

Tuxan (George Peppard) is a ruthless agent who will do anything to keep his country secure – even if it means spying on and abusing every citizen every minute of the day. He’s vicious and unsavoury and in the end the movie suggests that his actions are entirely justified. The people he abuses are primarily John David Welles (Michael Sarrazin), the sole survivor of an explosion at a space research facility named Groundstar, and Nicole Devon (Christine Belford), a woman who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time and finds herself caught in Tuxan’s net.

Under the opening credits, we see Welles running from the research lab as it explodes behind him. He’s massively injured and stumbles to a house nearby where Nicole has just arrived hoping for some quiet time to work out her life. Tuxan assumes that she must know Welles and is involved in what appears to be his plan to steal secrets about a new rocket fuel formula to sell to foreign interests. As Welles is gradually pieced back together by surgeons, it becomes apparent that his memory has been entirely wiped away. In order to draw out his foreign contacts, Tuxan arranges for him to escape and he finds his way back to Nicole, reinforcing the impression that she’s involved. But Welles is just hoping she can help him regain his memory.

Though Tuxan maintains close surveillance, including filming Welles and Nicole having sex – recordings he shares with various government officials for no apparent reason other than to illustrate just how invasive he’s willing to be to “protect my country” – Welles is grabbed by his enemy contacts who assume he still possesses the secrets they want. There’s a lot of running about, some violence, and a last minute twist which somehow tries to make Tuxan’s actions seem benign. The big problem is that The Groundstar Conspiracy ends up presenting a very elaborate scheme to bolster a rather trivial spy story. We find out at the end that all the plot mechanics are not really the point, that actually it’s been a psychodrama about grief, loss and redemption – but that theme comes out of nowhere, tacked on at the end.

*

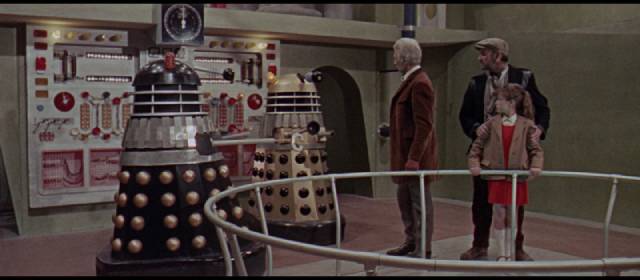

Dr. Who and the Daleks/Daleks: Invasion Earth 2150 A.D.

(Gordon Flemyng, 1965/66)

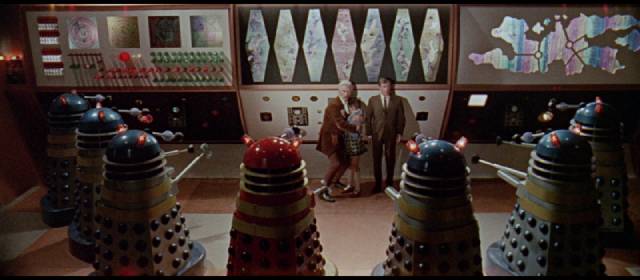

I was ten-years-old when I first learned of the pitfalls of adaptation. As a loyal viewer of Dr. Who on the BBC since the first episode aired in 1963, I was baffled and, yes, offended when Dr. Who and the Daleks arrived in theatres in the summer of 1965. I was obviously eager to see one of my favourite TV shows in colour and widescreen, but it had undergone confusing changes. The two most obvious: a redesign of the interior of the Tardis which had transformed the spare original with its central control console into a sloppy mess of loose wires and seemingly random handles and monitor screens, totally devoid of elegance or a sense of utilitarian logic; and a conception of the character totally at odds with what I saw every week on Saturday afternoons.

William Hartnell’s prickly, no-nonsense doctor had been transformed into a doddering, eccentric old granddad who had cobbled together a time machine in his back yard. In the early years of the series, the Doctor had not been fully defined … I can’t recall any mention being made during the Hartnell years of him being a Time Lord from some distant planet. In fact, a point was made of the uncertainty of his identity – it’s there in the title, Doctor Who? In the movie, he’s an old guy whose actual name is Who, living in London with his niece and granddaughter. His prissy, distracted manner is irritating from the first scene. Frankly, the Doctor is the worst performance the otherwise reliable Peter Cushing ever gave.

To add to the insult, scriptwriter and co-producer Milton Subotsky leaned hard on comedy in direct contradiction of the show’s value as horror for kids. The tone is totally condescending to its target audience and I sensed that even at the age of ten. Having set the wrong tone, and limited by a small budget, Dr. Who and the Daleks looks shoddy and poorly designed … and even restored and polished on Blu-ray, it still falls short in imagination and execution despite an occasionally attractive image.

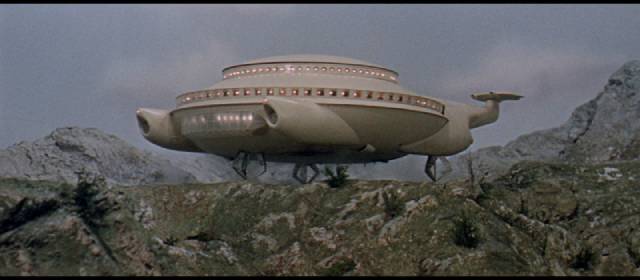

And yet, with the country in the grip of Dalekmania, the movie proved quite profitable and a sequel was immediately green-lit. Daleks: Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. (1966), although it retained some of the first movie’s flaws, proved to be a much better movie. This may in part be due to the fact that Subotsky’s script was apparently worked over by one of the series’ main writers, David Whitaker. The tone is darker and more violent, the budget is a bit bigger and the design much better. Maybe my reaction was more favourable because the setting is a war-torn future Earth which looks very much like the place I was growing up in – the ruins of London were just a more exaggerated version of what I had seen as a young child visiting the city before a lot of the destruction from World War Two had been completely built over.

The darker story also managed to tone down Subotsky’s tendency to go for laughs. The stakes are higher, so there’s not much room for comedy; and when it does rear up, it stands out as inappropriate. I still dislike Cushing’s interpretation of the character, but the apocalyptic tone and some pretty impressive model work make him easier to ignore.

Both movies were Amicus productions in everything except name – Subotsky and partner Max J. Rosenberg opted to use a separate company because the association of Amicus with horror might have caused parents to keep their young children away. Maybe they were right; the darker sequel was less successful at the box office. Glaswegian director Gordon Flemyng, who worked mostly in television, does have an obvious knack for composing with the wide Techniscope frame which makes the second movie in particular visually interesting, even if the scripts are flawed, pacing erratic and tone inconsistent. Yet again, these disks bring back a significant part of my early movie viewing.

*

Rounding out my recent Kino horror viewing are a couple of movies I didn’t see in my formative years. In fact, I first saw both in the early 2000s when they appeared on DVD.

The Oblong Box (Gordon Hessler, 1969)

I like the brief series of horrors made at the beginning of the ’70s by director Gordon Hessler from scripts written or co-written by Christopher Wicking – Scream and Scream Again and Cry of the Banshee (both 1970) and Murders in the Rue Morgue (1971); quirky, with a skewed approach to familiar genre elements which makes them at times surprisingly unconventional. Their first collaboration, however, is a frustrating mess.

The Oblong Box (1969) was originally planned as Michael Reeves’ follow-up to The Witchfinder General (1968), but when Reeves died, American-International producer Louis M. Heyward passed it on to Hessler, and Wicking did some rewrite work on Lawrence Huntington’s script, which like so many “Poe adaptations” had little to do with the famous author’s work. Aristocrat Julian Markham (Vincent Price) has returned to the family estate in England bearing a dark secret from his plantation in Africa. That secret is a brother driven mad by a witch doctor’s curse, kept locked in the attic. This puts a crimp in Julian’s relationship with fiancee Heidi (Uta Levka).

When Edward Markham (Alister Williamson) escapes, there are some random murders before we get to the revelation that the curse involves some large, ugly boils on his face and that it was inflicted on him for something Julian himself had done (trampling an African boy to death with his horse). To get to that point, the movie rambles randomly from one disjointed incident to another. Edward is a clumsy monster, more pathetic than menacing, while Julian is revealed to be a privileged asshole.

Although shot by John Coquillon, who had shot Witchfinder General and would go on to work with Sam Peckinpah on Straw Dogs, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and Cross of Iron, The Oblong Box lacks the stylish look of Hessler’s later horrors. For a better horror story about colonial misdeeds returning to England with a vengeance, see John Gilling’s Plague of the Zombies (1966).

*

The Face at the Window (George King, 1939)

Hearkening back to an older type of horror, George King’s The Face at the Window (1939) is an absurdly entertaining melodrama in the moustache-twirling Victorian style, the story quite nonsensical and the villain performed with full-throated theatrical panache by the inimitable Tod Slaughter, who worked his magic many times in movies directed by King in the ’30s. Here, Slaughter is the Chevalier Lucio del Gardo, a scheming aristocrat who offers to bail out the struggling bank of Monsieur de Brisson (Aubrey Mallalieu) in 19th Century Paris. To seal the deal, he insists that the banker’s daughter Cecile (Marjorie Taylor) must marry him.

Cecile, however, is in love with her father’s lowly clerk Lucien Cortier (John Warwick) – a completely unsuitable match in her father’s eyes. The Chevalier schemes to frame Lucien for a crime to get him out of the way. All quite reasonable for a romantic melodrama. Meanwhile, however, Paris is being terrorized by a series of brutal murders attributed to a werewolf, each crime accompanied by the appearance of a monstrous face at the victim’s window accompanied by menacing animal howls. As if that isn’t enough, Lucien’s friend Professor Le Blanc (Wallace Evennett) has developed a technique using electricity to induce a dead animal – or human – to complete the last action it was performing at the moment of death.

That last is really gilding the lily, particularly because in the event it’s not actually used to reveal the murderer – or rather the revelation is made by faking the technique which is so implausible that it shouldn’t really convince anyone. But it is entertaining. Just one more absurd detail packed into an already crowded sixty-five minute running time.

*

All these Kino disks offer decent transfers and at least a commentary track, with a few of them also including a featurette or two.

______________________________________________________________

(1.) The history of home video is littered with bright spots that flared and died too quickly, one of these being the DVD label CasaNegra, a boutique label specializing in Mexican horror created by Panik House Entertainment. They released less than a dozen titles, the majority in 2006, before folding in 2007, and I have most of them in my collection. The transfers are excellent for the time and the disks have a number of text extras, plus commentaries on five of them. Why these films have not turned up again is a mystery; they all deserve Blu-ray restorations with supplements filling in the history of Mexican genre cinema beyond the ubiquitous luchador movies. I’d certainly buy a box set! (return)

Comments

Wow, I haven’t thought of these titles in a long, long time. I really liked Killdozer when I first saw it back in the 1970s… I’d read the Sturgeon story, so I guess I was just happy to see a movie based on SF I’d read. I had the same reaction to you to The Groundstar Conspiracy… although I thought the TV ads were pretty good. As well, a similar reaction to Dr Who and the Daleks when seeing it in the theater… watching it, I couldn’t figure out why the Daleks had scared the poo out of me as a kid.

Yeah, it’s hard to recapture the frame of mind we had as kids watching Dr. Who. I can remember other creepy things that later in life just looked cheap and silly. Kind of a pity we lose that kind of imaginative openness…