Recent BFI releases

It’s been a while since I bought any BFI releases. I used to order them regularly from Amazon UK, but that tapered off when Amazon changed their shipping policies and prices escalated. (It wasn’t possible back then to order directly from the BFI because they wouldn’t ship overseas – that seems to have changed at some point, so I may get back to checking out their releases on a regular basis.) A few recent BFI releases did turn up at DiabolikDVD and I added them to an order I was making. One was a new Flipside two-disk set of theatrical shorts, Short Sharp Shocks (1949-80), which fits in with the sub-label’s well-established profile. The other, though, was quite unexpected.

Dementia/Daughter of Horror (John Parker, 1953)

I first heard about John Parker’s short feature Dementia (1953) when I read the brief essay about its variant version Daughter of Horror (1957) in Re/Search’s volume about fringe movies, Incredibly Strange Films, in the mid-’80s, and not long after that I found a rental copy of Something Weird Video’s VHS release. That had me hooked, and I was thrilled when Kino released the film in both its versions on DVD in 2000. That’s the edition I’ve made do with for two decades, but now here it is on Blu-ray, restored by the Cohen Film Foundation in 2015, looking much better than I’ve ever seen it before – at least Dementia does; Daughter of Horror is still in rough shape, unrestored and exhibiting a fair amount of print damage.

John Parker came from a movie theatre-owning family and at some point decided to try his hand at filmmaking. When his secretary Adrienne Barrett told him a disturbing dream she’d had, he set out to make a short film based on it. After shooting some material, he decided to expand it to a short feature (ultimately running fifty-six minutes). The resulting movie ran into distribution problems, in particular being banned by New York censors (it was also banned in Britain until 1970), and was eventually bought by producer Jack H. Harris, who re-edited it a bit and added some overwrought narration (spoken by Johnny Carson sidekick Ed McMahon), releasing it in 1957 as Daughter of Horror and giving it a boost by incorporating it into The Blob (Irving S. Yeaworth Jr, 1958) as the movie being screened when the alien slime invades a small-town theatre.

Some movies seem quite inexplicable and therein lies their interest. Dementia is like that, though it’s also much more. Parker never made another movie, so there’s really no context through which to understand where it came from. There are obvious echoes of film noir in its high-contrast black-and-white imagery and its seedy milieu, but those echoes seem to arise more from the obvious influence of German silent Expressionist cinema … that is, there’s a shared root rather than a direct connection. Like so much of Weimar cinema, Dementia is steeped in perverse sexuality and psychopathology, the influence of Freudian psychology reflecting a tendency in Hollywood throughout the 1940s and ’50s. But the film is perhaps not as obvious in this as some of its original critics asserted.

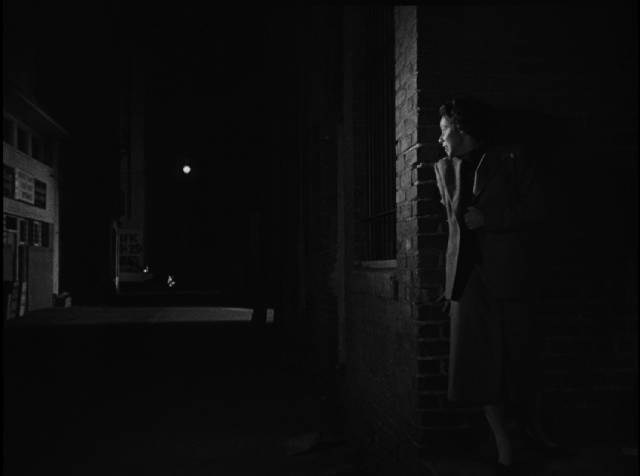

In Parker’s original version, devoid of dialogue or narration, viewers have to find their own way through the fever-dream narrative. With its Expressionist exaggerations and obviously subjective relationship to events which blur dreams and memories and possibly “real” violent events, we are forced to identify with a protagonist who remains in some ways stubbornly inaccessible. This is the Gamin (played by Parker’s secretary Adrienne Barrett), who wakes in a seedy flophouse room intermittently lit by the flashing neon hotel sign outside the window. This is a matte shot, with an obviously fake city skyline already establishing a distance from reality.

She lights a cigarette and walks to a mirror, pulling at her face and distorting her reflection as if looking for a lost sense of self before taking a flick knife from a dresser drawer. Leaving her room and walking down the stairs, she has two encounters which immediately establish an unsettling sense of family as something fraught with uncertainty and danger: she watches a cop dealing with the aftermath of domestic violence, a woman displaying bruises, an unshaved, sullen, possibly drunk man being hauled away; and a small child sitting on the stairs who holds out a toy towards the Gamin, who stares back at him with an unreadable expression, as if the boy is something quite alien to her.

Out in the street (shot in Venice, with visual echoes of other American Expressionist movies like Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil [1958] and Curtis Harrington’s Night Tide [1961], which both used the same or nearby locations), she is accosted by a drunk; as she tries to free herself from his grip, a passing cop car stops and a seedy-looking detective brutally beats the drunk with a club as the Gamin watches and laughs. Further down the street, she buys a paper from a newsboy (Angelo Rossitto), who gleefully points out the headline about a fatal stabbing, which she looks pleased about. Another unsavoury man joins her as she keeps walking and a limousine pulls up; the man apparently pimps the Gamin to the rich fat man in the back seat and she gets in. As the car pulls away, she seems annoyed that the fat man doesn’t show any interest in her … at which point, the film drifts into a highly stylized memory.

The Gamin walks through a graveyard at night with mist drifting among the headstones. A faceless figure approaches and draws her attention to a pair of graves. A woman slouches on a couch reading a magazine, ignoring a man, apparently her husband, who becomes angry and shoots her; the Gamin’s younger self approaches him from behind and stabs him to death … and we return to the back of the limousine as it pulls up at a nightclub. Although this seems like a pat explanation for the Gamin’s hang-ups, over-determined by Freudian implications of violent family trauma, it serves more as a reinforcement of the film’s nightmarish mood of sexual confusion and violence than an actual narrative explanation of events; its stylization may even suggest that this is a post-facto construction to justify the Gamin’s violent response to her own confusion about sexuality.

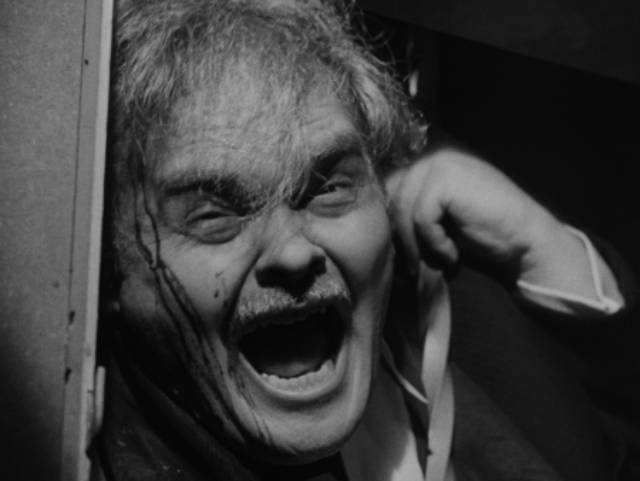

In the crowded nightclub, the fat man (Bruno Ve Sota, who also co-produced and probably contributed to the script) continues to ignore her, and from across the room the seedy detective (Ben Roseman, who also plays the Father in the memory) watches her, laughing as if he knows something she may not even be aware of herself. The fat man eventually takes her home, continuing to ignore her as his butler brings him a plate of greasy chicken; with the Gamin watching from the background, the fat man looms in closeup as he devours the chicken, his face and hands gleaming with grease. The Gamin’s frustration escalates and, after he finishes eating, she approaches him – but the seeming sexual tension shifts as she takes out her knife and stabs him; surprised, he falls from the open window.

A superficial interpretation suggests that her actions are a result of sexual abuse and exploitation, and yet (as Kat Ellinger points out in her commentary), she seems equally driven by frustration about being ignored, caught in a state of tension between desire and repulsion which can only be satisfied through violence. She has a brief, almost ecstatic moment of abandon in another nightclub where she sways erotically to the music before the detective and eventually the dead man himself close in, the events of the narrative piling on her before she wakes yet again in that flophouse room, the unresolved nightmare of her trauma cyclically repeating as the camera pulls back out of the window.

Dementia is Lynchian avant le lettre, a hothouse psychosexual nightmare in which we become trapped in the distorted subjective experience of a damaged mind struggling, and failing, to come to terms with the forces which have shaped her.

It’s interesting to consider why the censors found it so disturbing. Certainly not because it’s particularly graphic in its violence; perhaps more because that violence is visited on men, directly and indirectly, by a woman whom the narrative doesn’t condemn. Was it considered too subversive because it sticks so closely to her point of view? (In a text card before the film starts, none other than writer-director Preston Sturges offers a rousing endorsement of Dementia as a “work of art” which “stirred my blood, purged my libido”, suggesting that it provides a form of sexual release not commonly found in Hollywood product.)

Daughter of Horror became the better-known version, perhaps because Harris’ tampering mitigated the “problem” by adding the bombastic narration which very deliberately creates some distance between the audience and the Gamin and imposes a constant stream of moral judgment about her psychological defects which is generally absent from the original film. That is, the revision does what it can to domesticate something wild, to normalize the abnormal and bring it back to something closer to Hollywood convention where transgressions are met with some final judgment and a fitting punishment. Because of the nature of the original film, this attempt isn’t really successful, but the lip-service it pays to mainstream morality was perhaps enough to make Daughter of Horror more palatable.

In addition to both versions of the film, the BFI dual-format release includes the typically lively Kat Ellinger commentary, a brief restoration comparison, Joe Dante’s Trailers from Hell commentary, and Alone with the Monsters (1958), a short film made by Nazli Nour when she was a 17-year-old drama student, about a lonely old woman driven to suicide by the callous cruelty of other people, photographed by the great Walter Lassally.

*

Short Sharp Shocks (Various, 1949-1980)

The Short Sharp Shocks two-disk set is a mixed bag of short films (ranging from fourteen to thirty-seven minutes) made to play in support of theatrical releases back when cinemas offered a programme rather than just a main feature. The nine films included span from 1949 to 1980 and all lean towards horror. The short form has both inherent advantages and disadvantages; impact isn’t dissipated by the need to elaborate on narrative incidents, but there’s little time to develop characters in depth. With few characters and limited to one or two sets, several have the feel of television dramas.

in Anthony Gilkison’s Lock Your Door (1949)

The first two, made in 1949 by Anthony Gilkison, are monologues by the great writer of horror stories Algernon Blackwood, then 80, shot on a set which looks like the sitting room of a private club. In each, Blackwood tells a ghost story in cosy surroundings, each essentially a brief uncanny anecdote rather than a fully formed narrative: in Lock Your Door, a nervous woman takes shelter in a remote cottage which is apparently haunted, while The Reformation of St Jules describes a strange religious vision on the Riviera. J.B. Williams’ The Tell-Tale Heart (1953) is similar, though more intensely dramatized as Stanley Baker recites Poe’s famous story in a stylized garret set, slipping back and forth between the writer creating the story and the protagonist going mad within it.

Theodore Zichy’s Death Was a Passenger and Portrait of a Matador (both 1958) are the most conventional films in the set, one involving a chance encounter on a train which triggers memories of a wartime incident on another train in Occupied France, the other dealing with an artist haunted by his own painting of a matador who died just after it was finished.

In Brian Cummins’ Twenty-Nine (1969) Alexis Kanner is a heavy-drinking unfaithful husband who wakes up in a strange flat, dressed in strange clothes, and desperately tries to remember what he did the previous night. There are suggestions of danger, though the final revelation dissipates them.

The longest film is also the most overtly exploitative. Derek Robbins’ The Sex Victims (1973) promises sleaze and provides a certain amount of nudity as a truck driver on a country road sees a naked woman on horseback riding into nearby woods and pursues her. A sexual encounter takes on disconcerting undertones, with the woman seeming to be the ghost of someone raped and murdered in the woods.

Lindsey C. Vickers’ The Lake (1978) is a conventional horror story about a young couple who make the mistake of having a picnic by a lake near a house where a violent crime once occurred. As the afternoon unfolds, a malevolent force attacks them. They’ve done nothing to deserve what happens so the film has an arbitrary cruelty about it.

Finally, Nigel Finch’s The Errand (1980) was written and produced by prolific horror film writer David McGillivray (perhaps best known for the scripts he wrote for Pete Walker). In a dystopian alternate England, a young soldier is sent on a mission with unclear purpose and finds himself at the mercy of the various people he encounters, ultimately discovering that the mission is intended to lead to his own death.

Overall an uneven collection, but the BFI has packed the disks with interview extras: Twenty-Nine producer Peter Shillingford (42 minutes) and script supervisor Renee Glynne (15 minutes); Kate Lees of Adelphi Films (37 minutes) on the family business and the rediscovery of the long-thought-lost Tell-Tale Heart; co-star of The Lake Julie Peasgood (18 minutes); and most entertaining, David McGillivray (43 minutes) on his career and his first producing effort on The Errand.

Comments