Guest Post: From Film to Flipbook to Film

As anyone who has followed media coverage over the past year knows, the persistence of the Covid-19 pandemic has spurred the arts world to reconfigure strategies for presenting exhibitions and sustaining audiences. An example of this strategy is the on-line film presentation “Discovering Lost Treasures in Fin de siècle Flipbooks” by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival (SFSFF) on April 11. The event was introduced by British film historian Pamela Hutchinson (author of the BFI monograph on Pandora’s Box) who in turn introduced restoration expert Robert Byrne and the French film researcher Thierry Lecointe. Lecointe has unearthed a collection of what today are called flipbooks, palm-sized books which reproduced sequential still images from films originally made between 1896 and 1901 during the first decade of cinema. The books were originally made by an obscure Parisian bimbelotier (a maker of trinkets, toys and other playthings) named Léon Beaulieu. Beaulieu remains a mystery man; he appears to have had five different addresses during the years associated with the flipbook production, he was imprisoned for a time and he died just 43 years of age.[1]

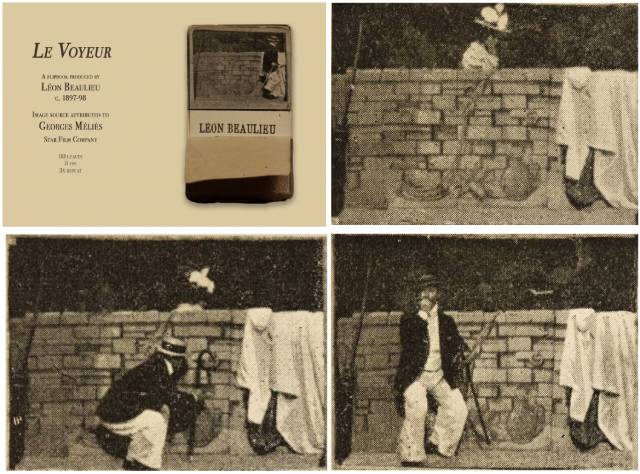

There are a total of 27 flipbooks from the Beaulieu collection; they include familiar material from filmmakers such as Georges Méliès, the German Skladanowsky brothers and from the Pathé, Gaumont and Edison studios. Some of the flipbooks were made from films now lost. The SFSFF undertook the task of reanimating the collection, essentially reversing Beaulieu’s process from paper back to film. However, as Lecointe demonstrated for the camera, the original flipbooks were not uniformly assembled; not only are they of various thicknesses, but of different dimensions of width and height. The lack of uniformity made the transfer back to film a tricky operation but as Bryne also explained, by adjusting individual pages next to a mirror, the central portion of each page could be photographed steadily even as the outer edges jiggled a little. Note too that the films are very short—most just 12 to 15 seconds—so in the presentation each was shown twice. Despite the low resolution of the original images on paper (the equivalent of 0.5K in clarity) the films were wonderful to behold, with a few revelations.

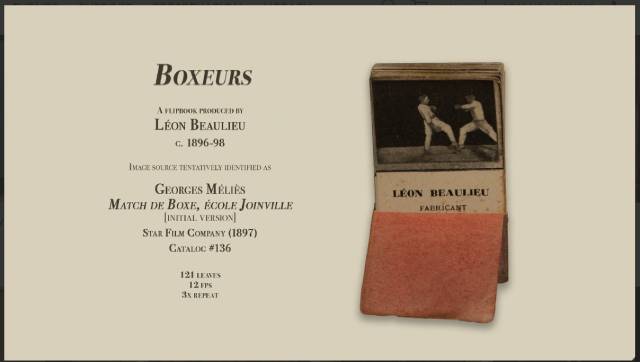

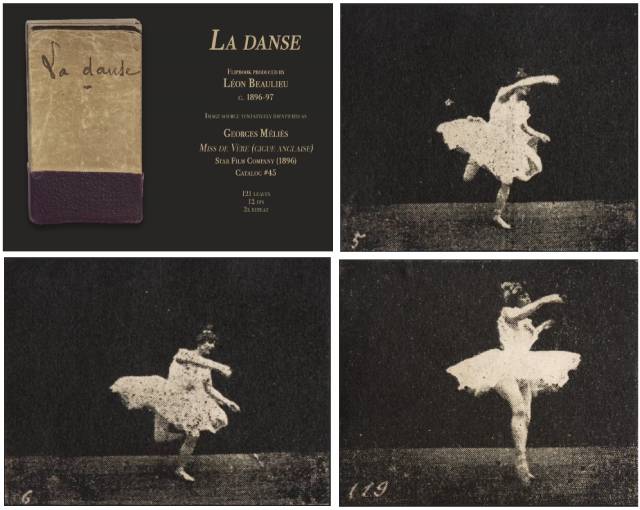

Some of the films conform to familiar categories of early cinema; for instance, the early Méliès film Arrivée du Train (circa 1896) is an imitation of the Lumière actualité from 1895 complete to the camera’s positioning so that the train enters the station at a dynamic diagonal. La Danse (c. 1896-7) showing Elise de Vère dancing an English jig, her figure standing out against an entirely dark background, is a good example of what Tom Gunning dubbed “the cinema of attractions.” Another film demonstrating the more familiar serpentine dance identifies the dancer on the cover of the flipbook incorrectly as the recognized star of this sub-genre, Loie Fuller. However, research has not yet clarified who this artist is. Boxeurs (c. 1896-8) recalls the Black Maria-set Glenroy brothers boxing match from the Edison studio although the flipbook image of the boxers here looks to have been more deliberately traced, flattening the figures and giving them the appearance of a stencil.

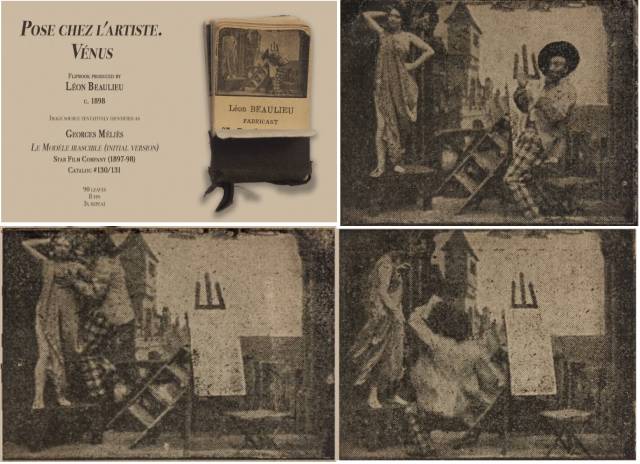

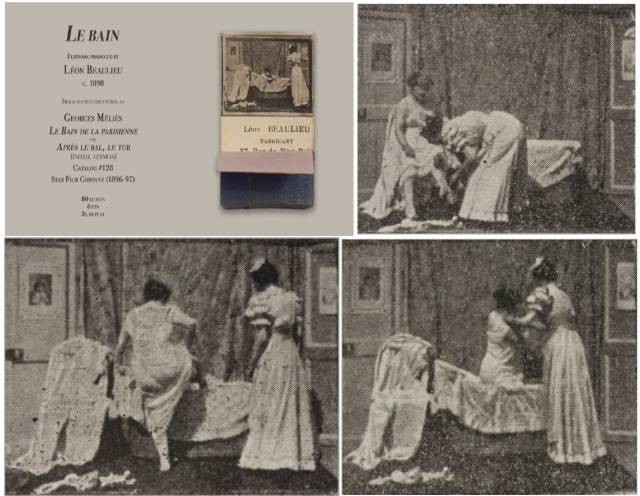

Of the total of eleven films, six have a curious, although on consideration, perhaps not surprising similarity: they highlight the female figure in a state of semi-undress, most often in the privacy of the boudoir. Le coucher de la Mariée / Woman Getting into Bed (c. 1898) is the simplest of this sort: assisted by her maid, a woman removes some outerwear and climbs into bed. (This film is a good example of how the flipbook to film process can restore a film once believed lost.) Two others, Nuit Agitée / A Terrible Night and La Puce / The Flea are variations on this simple, essentially voyeuristic action: in the first, a woman is awoken, agitated by a dream; in the second, an insect causes the woman to jump out of bed and proceed to frantically grope inside her nightgown. More provocative is Le bain (c. 1898) in which a woman, still partially dressed, enters a bathtub whereupon a maid removes her upper gown. Three other films build on the risqué element by including a male figure. Pose chez l’Artiste, Venus / The Irascible Model shifts the action from the boudoir to an artist’s studio where the male painter makes a predatory advance on the model and is swatted away. The more boldly titled Le Voyeur by Méliès (c. 1897-98) has a studio-shot exterior location. A brick wall, shoulder-high, separates foreground from background. A young man notices a young woman behind the wall, then ducks down to peer through a crack in the wall. Then with a wink at the frontal off-screen space, linking his reaction to that of the male viewer, he leaves the frame.

The gem of the entire presentation is L’Amant surpris / The Surprised Lover (Melies, c. 1898-1900). This is not only the boldest of the risqué films, most interestingly, it conveys the degree to which the narrative impulse was at work in cinema as early as the years following Lumière’s premieres. In just 14 seconds, the action moves quickly, conveying a range of emotion. A woman’s bedroom: a man and woman stand close to each other. The woman begins to disrobe, then stops. The man encourages her to continue. With the blunt gesture of extending the palm of her hand, the woman clarifies their relationship. The man raises his hands indicating his inability to pay for her services. She in turn ceases to play her role, an act of resistance that causes him to raise his hand in a threatening manner. Suddenly another man bursts from the left frame and proceeds to chase the customer out of the room. Admittedly, the action is too rapid to convey nuances of expression; still, here is the dramatic sequence-shot in its nascence that Griffith and Feuillade will master in the new century.

____________________________________________________

(1.) A book of the Beaulieu collection, Discovering Lost Films of Georges Méliès in Fin de siècle Flip Books 1896-1901 by Thierry Lecointe, Pascal Fouche, Robert Byrne and Pamela Hutchinson has been published by John Libbey. The presentation films and others can be viewed at silentfilm.org. (return)

Comments