Home-Grown Horrors

The new box set from Vinegar Syndrome is a close cousin to Arrow’s American Horror Project sets. Home-Grown Horrors collects three low-budget regional movies from the ’80s, gives them surprisingly good transfers, and surrounds them with copious extras to provide an account of do-it-yourself filmmaking on the fringes of genre exploitation. But while the Arrow sets focus for the most part on the professional fringe of the business, Vinegar Syndrome has unearthed three movies which are the equivalent of enthusiastic kids “putting on a show” in the barn out back.

If I had to come up with a reason for why these movies appeal to me, it’s probably because I know how hard it is to make something with very limited resources, the sheer effort involved – not to mention the conflicted feelings that stem from taking advantage of other people’s time and generosity; it took me more than a year to make my short sci-fi comedy The Adventures of Stella Starr back in the early ’90s and almost thirty years later I still feel guilty about what I put a helpful group of friends through! So the mere fact that a filmmaker manages to see a project through and maybe shows glimpses of creativity in the process deserves recognition. And when those filmmakers manage to come up with something interesting with flashes of originality, they deserve to be acknowledged and perhaps even appreciated. It’s nice to see a company like Vinegar Syndrome not only preserving these efforts, but actually lavishing financial and technical resources on them.

Two of the films in this particular set were protracted labours of love, their production stretched out over a couple of years, while the third was essentially an ambitious film school project. Naturally, none of them could stand against mainstream genre movies either technically or creatively, but they’re all buoyed up by that enthusiastic can-do spirit which goes a long way towards compensating for their shortcomings.

*

Fatal Exam (Jack Snyder, 1990)

Although it’s impossible to apply an objective scale, for me the weakest movie in the set is Jack Snyder’s Fatal Exam (1990), made on weekends over an extended period. The most conventional of the three, it suffers particularly from Snyder’s decision (need?) to do too much himself – he wrote, produced, directed and edited it himself, which is not unusual, but it’s obvious that he needed someone else’s input in the editing room. At an exhausting 112-minutes, the movie tries the viewer’s patience and leaves far too much time to contemplate its weaknesses. But that said, there are moments when the pacing produces odd effects which you wouldn’t get in a “better-made” movie – like the scene in which a character keeps reaching into a cooler and pulling out another drink can, cracking it open and taking a sip, before reaching for another while the people he’s talking to say nothing about the fact that he’s using up all their refreshments; or the scene in which another character sees a severed head inside the cubby of the coffee table and wakes everyone up, only to have no one else bother to look to see what’s got him so panicked.

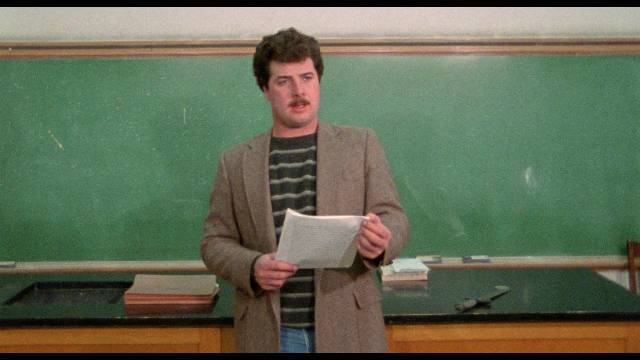

The set-up is fairly formulaic. The prof in a university course on the paranormal sets his students a year-end assignment to spend a weekend in a remote house which has been empty since a man brutally murdered his family a few years earlier. The object is to look for ghostly manifestations, but the students are more interested in drinking beer and smoking dope. After a lot of filler, one or two of them start to see things – the bloody murder of the wife in the bedroom, that severed head in the coffee table – and people start to disappear. Because it takes so long for Snyder to tell the story, the big reveal is easy to guess long before the movie gets to it. We know who’s engineering events to build to a human sacrifice which will result in the villain gaining infinite power and immortality from the Devil.

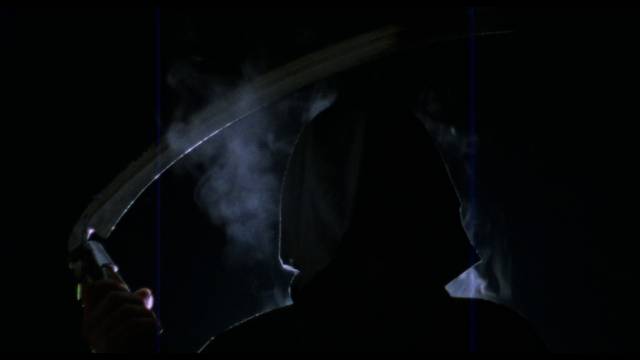

But that end section in the sprawling labyrinth of cellars beneath the house picks up some energy – there’s a cloaked figure wielding a deadly scythe who dispatches a few victims – and best of all the manifestation of the Devil is rendered via a stop-motion puppet which adds an unexpected note of humour and imagination like a small reward for having been forced to sit through all the preceding sluggish plotting.

Vinegar Syndrome’s 2K transfer from the original 16mm negative looks surprisingly good, with solid colours and a decent amount of detail. The disk also contains a commentary with director Snyder and members of the cast and crew, plus a forty-eight minute retrospective making-of which covers in a lot of detail what it takes to make a feature with few resources.

*

Beyond Dream’s Door (Jay Woelfel, 1989)

Jay Woelfel’s Beyond Dream’s Door (1989) is in many ways the best film in the set, certainly the one which displays the most filmmaking talent and ambition. If time and resources didn’t quite stretch far enough to fulfill all of Woelfel’s intentions, the result is nonetheless a fairly impressive horror-fantasy with a strong visual sense and better narrative pacing than Fatal Exam. Its biggest weakness is a collection of uneven performances from a largely inexperienced cast.

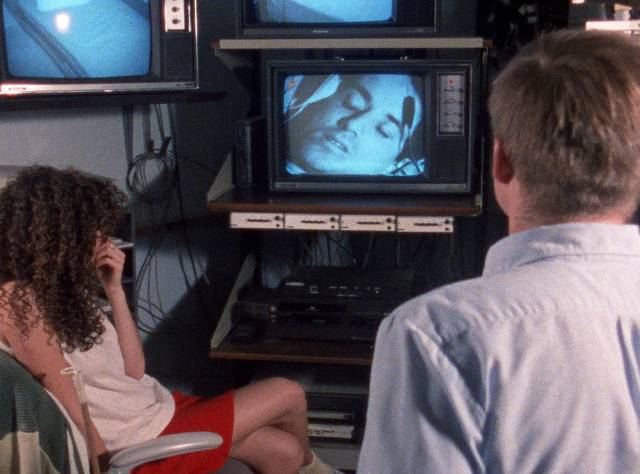

Having been unable to secure the rights to some Ray Bradbury stories, Woelfel wrote an original script which shows some influence from both A Nightmare on Elm Street and Phantasm, but draws more significantly from the stories of H.P. Lovecraft – not directly, but rather in tone and general theme. A university student studying psychology begins to have nightmares which seem to be rooted in suppressed memories, though those memories are of a family he never had. Violence and monsters pursue him in his sleep, only to begin manifesting in the real world – somehow, his dreams are opening a door to another dimension and things are beginning to come through, pursuing him and killing people around him.

Effectively shot by first-time cinematographer Scott Spears, who went on to a fairly prolific career, with pretty good low-budget monster FX, the movie generates atmosphere by blurring the lines between the dream realm and reality as Wes Craven and Don Coscarelli did in their work. Despite the uneven acting, Woelfel knows how to use the camera and construct scenes for increasing tension; although coloured gels are used, suggesting a familiarity with Bava and Argento, the shifts from dream to an increasingly dangerous reality are well-crafted to keep the viewer uncertain and on-edge.

The over-stuffed disk includes no less than four commentaries – two new, two archival – with Woelfel and various members of the cast and crew; a 41-minute retrospective making-of; several featurettes about the production, with behind-the-scenes footage, bloopers, the monster effects, alternate unused footage, deleted scenes, effects tests and local news coverage. There’s also the original 1983 21-minute short film that Woelfel based the feature on, which comes with its own commentary and short making-of, plus two other short films with their own commentary tracks.

*

Winterbeast (Christopher Thies, 1992)

If Fatal Exam is a bit of a slog and Beyond Dream’s Door is an impressive if flawed horror fantasy, Christopher Thies’s Winterbeast (1992) is a baffling, bat-shit-crazy experience. Winterbeast gives the impression that it was made by people who had never actually seen a movie before, but had only heard about them second-hand. Actually, given the strangeness of the performances, maybe it was made by aliens whose only knowledge of human behaviour had been gleaned from old B-movies. Strangely paced, filled with endless non sequiturs, the movie induces an odd trance-like state of mind, though not a pleasantly relaxing one. There were moments when I felt like my head was going to explode, but then the tension would abruptly break and I would be laughing out loud.

Shot in bits and pieces over a period of years, using multiple different cameras and film stocks, both 16mm and 8mm (and at one point on video, though that footage wasn’t ultimately used), the movie is a ragged patchwork which seems to have been made up moment by moment, depending on who was available that particular weekend and what anyone could recall of what had already been shot.

Is there an actual story? You tell me. There are some park rangers working on a mountain with a resort lodge nearby. There have been a number of disappearances – tourists and rangers – and they want the lodge to close until the mystery can be solved. But the lodge owner refuses … for reasons which may or may not eventually become clear. Up on the mountain looking for the missing people, the rangers discover a clearing in which a number of uncanny Native totems have been erected. They sense some strange power and a number of monsters show up and kill people. Apparently, there’s a curse on the mountain which protects the sacred place from intruders. Or something. Events seem random and isolated, concocted for themselves rather than to advance a plot.

Beyond this raggedness, many scenes are shot Ed Wood-style with actors posed in a static frame spouting dialogue to one another for long periods – sometimes expository, sometimes a propos of nothing. The rangers’ office and the lodge foyer appear to be the same corner of a studio space with a few changes in set dressing – again, Ed Wood-style. The sense of inertia engendered is one of the main causes of that feeling of pressure building in the viewer’s brain. When some kind of characterization is attempted, it seems random and disconnected, particularly the snarky ranger who wears sunglasses and speaks abrasively to everyone.

How much of what we see was intentional, how much self-aware remains uncertain. Some things seem simply incompetent – there’s an electric clock on the ranger office wall with the cord hanging down, for instance, obviously not plugged into a socket. Is it there as a signal to the audience, or did no one on the set care? But when the rangers stop for a beer, one of them has a small box full of knick-knacks from which he takes a small protective talisman – and there in the box, in plain sight, is a very life-like dildo which no one comments on. That seems obviously put there to elicit a laugh (which it does), suggesting that much of what we see is deliberate, a joke intended by the filmmakers, although delivered with dead-pan seriousness.

Acting honours, if you could stretch a point, have to go to Bob Harlow, who plays lodge owner Dave Sheldon in a one-of-a-kind performance (literally: this was apparently the only movie he ever appeared in), so bizarrely eccentric that it outshines even the various monsters which show up to bite people’s heads off. Late in the film, he has a show-stopping scene which brings to a peak your feelings of fascination and disbelief, the inability to discern whether this is sheer incompetence or comic genius creating such tension that you either have to submit unconditionally or give up watching altogether.

As if all the puzzling human activity weren’t enough, the monsters are all produced with crude but utterly endearing stop-motion animation, almost formless clay puppets as if a low-budget kids’ show had gone rogue. There’s a tree monster which shows up to create an opportunity for a brief moment of gratuitous nudity, an almost formless blob thing that hauls a climber up a cliff on his rope and bites off his head, a couple of goblin critters that break out of the ground during an earthquake and grab a couple of hikers … these all convey a feeling that the filmmakers are indulging themselves in the simple pleasures of play for its own sake, a feeling which spills over into the live-action scenes to make incompetence itself seem charming. Of the three movies in the set, this one feels most like kids putting on a show in the barn, careless of audience expectations, just for the fun of doing it.

Given that Winterbeast was the only movie almost everyone in the cast and crew was involved with, it’s amazing that it has survived to be resurrected by Vinegar Syndrome in what amounts to a deluxe Blu-ray. Not only have they scanned the original 8mm and 16mm elements in 2K for a surprisingly attractive film-like image; they’ve packed the disk with extras. There are two commentaries, one new with producer Mark Frizzell, one archival with Frizzell, director Thies and cinematographer Craig Mathieson; an alternate version scanned from an unfinished workprint; a lengthy new interview with Frizzell; four interviews with cast members – Charles Majka, David Majka, Dori May Kelly and Mike Magri; a 20-minute archival making-of; a collection of deleted scenes; a brief audio interview with score composer Michael Perilstein (one of the few participants who had a career beyond this movie); a few scenes edited from the unused video footage (the “soap opera” cut); and a 19-minute adulatory appreciation by filmmaker Simon Barrett, who discovered the movie on VHS and became a fascinated fan.

*

With Arrow’s American Horror Project seemingly stalled, let’s hope Vinegar Syndrome will continue to fill gaps in genre history with more sets like this. There must be many more movies like these out there waiting to be rediscovered.

Comments